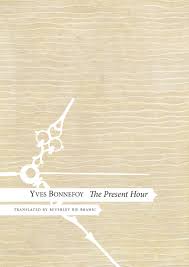

Last Saturday I attended one of the half-yearly poetry events in Palmers Green, north London. These are always very good evenings, these days full of music as well as poetry as the Helios Consort of recorders play before and after the interval. Kevin Crossley-Holland was reading (a superb poet, as well as all his other literary achievements) as was Sarah Westcott (recently published by Pavilion – having just won the Manchester Cathedral Poetry Competition) and Katherine Gallagher, launching her new Arc collection – about which someone called Crucefix has blurbed:

This new collection is bejewelled throughout with haiku-like moments of vivid observation. Her delighted responses – in particular to the natural world – serve to peel away the film of familiarity through which we usually gaze. Yet Gallagher combines such excited observation with a quality of restraint, a respect for what she encounters in a process of self-creation – “from myself into myself” as her epigraph from Rose Auslander puts it. Sequences about her Australian mother and the loss of her brother are imbued with this same gift: life is celebrated in poems that never forget our mortality: “This is time we have underlined, / remembering what we’ve done, where we’re going” (‘Quotidian’).

On the following morning I was taking part in the Bloomsbury Festival, talking about the art of translation with Chris Campbell, Literary Manager, Royal Court Theatre and Gregory Thompson, Creative Entrepreneur in Residence at UCL. Chaired by Geraldine Brodie, Lecturer in Translation Theory and Theatre Translation at UCL, the talk – in the very comfortable, wood-panelled surroundings of the Churchill Room, Goodenough College, London House, Mecklenburgh Square, London – was really wide-ranging from Gregory’s experiences of directing Shakespeare in the Indian sub-continent and the kind of cultural translation that takes place on such occasions to Chris’s translations of drama texts to and from the French and French-Canadian. One issue there is the translation of comic references such as cricket allusions or types of motor cars (I think he suggested a Vauxhall Cavalier equivalent in a French cultural context would be a Renault 21). I thought there was quite a bit of common ground when I was explaining how I fell into translation through the need to stand up and declaim/read/perform translations which I felt did not really convince in English. This is how I began the idea that I might try to translate Rilke’s 9th Duino Elegy many, many years ago – I could not find a version that read well aloud. I still regard that as a key test.

This idea that poetry ought to be read aloud is common enough in most writing workshops but I do wonder how many people really adhere to it. This came up again with my third engagement of the busy weekend – teaching my first session for the Poetry School on ‘music and metre’ on Monday evening. As I explained to the class, formal verse is not especially my thing but it is also an area I have had to teach on various occasions. I kicked off by reading James Fenton’s powerful poem ‘Tiananmen’ – see below – and Auden’s observations about the benefits of form:

The poet who writes ‘free’ verse is like Robinson Crusoe on his desert island: he must do all his cooking, laundry and darning for himself. In a few exceptional cases, this manly independence produces something original and impressive, but more often the result is squalor – dirty sheets on the unmade bed and empty bottles on the unswept floor.

I love the swipe at “manly independence” there. Not very surprisingly, this observation is quoted by Stephen Fry in his The Ode Less Travelled (Hutchinson, 2005) which also suggests modern poetry, because of its abandonment of formal constraints is now “laughably easy” to write. Elsewhere Fry describes most contemporary poetry as suffering from anaemia; it’s a lifeless trickle, rhetorically listless . . . Fry doesn’t mind setting himself up like this – and tucked away in the book you’ll also find his appreciation of Whitman, Anne Carson, Denise Riley and many others.

I told the class, having spoken to a fair number of poets recently about form, that they’d be surprised (or maybe not) how few published poets would confidently declare their own grasp of metrical matters. On the night, we didn’t get along as fast as I’d anticipated – there was good discussion, especially of the areas of inevitably uncertainty in scanning a poem etc – it’s like jazz?? – so I’m looking forward to picking up the themes again next Monday evening with Tony Harrison, Wordsworth, Stevens, Elizabeth Jennings . . .

Now I’m feeling a bit poetry-ed out. Coffee and cake are required . . . after this:

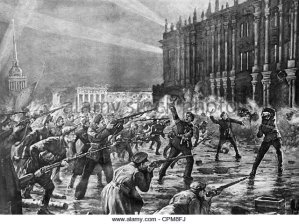

Tiananmen – James Fenton

Tianamen

Is broad and clean

And you can’t tell

Where the dead have been

And you can’t tell

What happened then

And you can’t speak

Of Tianamen.

You must not speak.

You must not think.

You must not dip

Your brush in ink.

You must not say

What happened then,

What happened there

In Tiananmen.

The cruel men

Are old and deaf

Ready to kill

But short of breath

And they will die

Like other men

And they’ll lie in state

In Tianamen.

They lie in state.

They lie in style.

Another lie’s

Thrown on the pile,

Thrown on the pile

By the cruel men

To cleanse the blood

From Tianamen.

Truth is a secret.

Keep it dark.

Keep it dark.

In our heart of hearts.

Keep it dark

Till you know when

Truth may return

To Tiananmen.

Tiananmen

Is broad and clean

And you can’t tell

Where the dead have been

And you can’t tell

When they’ll come again.

They’ll come again

To Tiananmen.

![disko_bay[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/disko_bay1.jpg?w=700)