As in the previous five years, I am posting – over the summer – my reviews of the 5 collections chosen for the Forward Prizes Felix Dennis award for best First Collection. This year’s £5000 prize will be decided on Sunday 25th October 2020. Click here to see my reviews of all the 2019 shortlisted books (eventual winner Stephen Sexton); here for my reviews of the 2018 shortlisted books (eventual winner Phoebe Power), here for my reviews of the 2017 shortlisted books (eventual winner Ocean Vuong), here for my reviews of the 2016 shortlisted books (eventual winner Tiphanie Yanique), here for my reviews of the 2015 shortlisted books (eventual winner Mona Arshi).

The full 2020 shortlist is:

Ella Frears – Shine, Darling (Offord Road Books) – reviewed here.

Will Harris – RENDANG (Granta Books) – reviewed here.

Rachel Long – My Darling from the Lions (Picador) – reviewed below.

Nina Mingya Powles – Magnolia 木蘭 (Nine Arches Press) – reviewed here.

Martha Sprackland – Citadel (Pavilion Poetry) – reviewed here.

There is such ease and (apparent) directness of communication between the voices in Rachel Long’s poems and their readers/listeners that they could easily be misjudged. Darling from the Lions is filled with chatty, slangy storylines, some close to sentimental, others genuinely shocking, but the book’s title is instructive. In Psalm 35, David pleads with his God to protect him from those that strive against him, the mockers and false witnesses. He cries out: “rescue my soul from their destructions, my darling from the lions” (KJV). The preservation of the self intact, or at least relatively unharmed, against the multitudinous, multivarious threats of a modern adult female life is Long’s real concern.

There is such ease and (apparent) directness of communication between the voices in Rachel Long’s poems and their readers/listeners that they could easily be misjudged. Darling from the Lions is filled with chatty, slangy storylines, some close to sentimental, others genuinely shocking, but the book’s title is instructive. In Psalm 35, David pleads with his God to protect him from those that strive against him, the mockers and false witnesses. He cries out: “rescue my soul from their destructions, my darling from the lions” (KJV). The preservation of the self intact, or at least relatively unharmed, against the multitudinous, multivarious threats of a modern adult female life is Long’s real concern.

Given this focus, the number of child’s eye view poems in the collection is not surprising. Readers will be reminded of Jeanette Winterson’s account of growing up in a Christian evangelical household in Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, and similarly here, religion proves more threatening than a source of safety. A young girl’s enthusiasm about staying up past midnight in ‘Night Vigil’ is clear: “How the minute and the hour stood to attention!” But the “smiling eyes” of the evangelist in the pulpit turn to “teeth” as he leads her, ominously, down and “incensed corridor, // and [she] followed”. The same threat seems more explicitly taken up in ‘8’ with its quotation from Psalm 51 as epigraph: “Purge me [. . . ] I shall be whiter than snow”. Long’s choices about form usually lead her to very free verse, controlled only by the colloquial voice and breath, but on this occasion the urgency and breathlessness of the 8 year-old child is reflected in unpunctuated, headlong, slippingly-enjambed, short-lined verse. What the child wishes to be cleansed of is an abusive sexual encounter, “that sunday / that school”, an incident in which she became “instantly older”.

Given this focus, the number of child’s eye view poems in the collection is not surprising. Readers will be reminded of Jeanette Winterson’s account of growing up in a Christian evangelical household in Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, and similarly here, religion proves more threatening than a source of safety. A young girl’s enthusiasm about staying up past midnight in ‘Night Vigil’ is clear: “How the minute and the hour stood to attention!” But the “smiling eyes” of the evangelist in the pulpit turn to “teeth” as he leads her, ominously, down and “incensed corridor, // and [she] followed”. The same threat seems more explicitly taken up in ‘8’ with its quotation from Psalm 51 as epigraph: “Purge me [. . . ] I shall be whiter than snow”. Long’s choices about form usually lead her to very free verse, controlled only by the colloquial voice and breath, but on this occasion the urgency and breathlessness of the 8 year-old child is reflected in unpunctuated, headlong, slippingly-enjambed, short-lined verse. What the child wishes to be cleansed of is an abusive sexual encounter, “that sunday / that school”, an incident in which she became “instantly older”.

Elsewhere, a child’s bicycle ride is likewise hedged around with vague threats of the “abbatoir” and startled invocations to “Run!” The inculcation of childhood religious belief again works as ironic backdrop:

Have you ever fled uphill –

hill of concrete,

acres of balconies identical

unanswerable doors –

reciting Psalm 23.

And in the extraordinary ‘Helena’ – the age of the speaker increasing still further here – we get a brilliant piece of ventriloquism as a young woman, who works in a seedy gentleman’s club, tells two women friends how she was all-but kidnapped by the bouncer, then raped, the man “acting out / some horror-porn shit” (Long’s unusual choice here of long, prosy lines of verse add to the almost unbearable intensity of the storytelling). These are some of the ‘lions’ by which the ‘darling’ is threatened. But ‘Hotel Art, Barcelona’, as the title suggests, indicates such threats come in all shapes and sizes and social/cultural guises. A young woman, in a relationship with a much older man, is staying in an expensive hotel. He’s concerned with their age gap; she with the fact she’s pregnant and he seems reluctant to acknowledge it. The power/wealth balance is unequal and, later, she allows him to fuck her on their balcony, her unconvincing/unconvinced question (“is love not this?”) left hanging in the air.

The Barcelona woman later throws up her expensively-bought dinner in the bathroom and there are other examples of purgative vomiting in Darling from the Lions. I’m not sure whether ‘The Clean’ is caused by morning sickness (as it is in ‘The Garden’) or an eating disorder, but the woman leans over the toilet bowl, insisting to herself, “Girl, you can be new, / surrender it all / into one bowl”. Often, the isolation of these female figures is relieved by examples of companionship with other women. ‘Sandwiches’ winds the clock back to school days again, as the narrator and her friend Tiff begin to experiment with their sexual attractiveness by stuffing unbuttered bread down their bras, because “the boys have clocked the difference between / a tissue and a tit, a sock and a tit, but not quite yet / a tit and a slice of bread”. This is a great example of Long’s brilliant control of timing, register and colloquial rhythm.

Funny though ‘Sandwiches’ is (and the poem is destined for many anthologies, I’m sure, where it’ll be taken out of context), the poem needs to be read alongside ‘The Yearner’, in which the woman deliberately sleeps on her own arm so that she can later re-acquaint herself with it, touching her numbed fingers like “strangers”, because her yearning is a dissatisfaction with how life has turned out, a wishing to be “another”. The opening section of the book is punctuated with 5 short poems, all called ‘Open’. They are about the seen and unseen. Watching a woman sleep, several people suggest she seems carelessly abandoned, surprised, working things out. Read the poems again and you see what the woman herself feels: it’s like she’s screaming, in hiding, or bracing for impact. She is beset by lions but it’s not always obvious to others.

The Psalmist’s cry was for protection by God, but it is Mum who affords most help in Darling from the Lions. The poems in the middle of the book are a hymn to the maternal figure, though the extent of her powers has already been shown to be compromised. ‘Referring to the House as the Whole Street’ is more plainly descriptive than most of Long’s poems, the mother returning after her night shift as a midwife, consoling herself as day breaks with sugared almonds, “in various shades of dawn”. Her care for her daughter is immediate, simple, physical: a cut finger is taken up and sucked. The mother spends all day Saturday plaiting her daughter’s hair into cornrows so she looks as “beautiful as Winnie Mandela!” It’s through the mother figure and several aunties that the religious element enters the household, the Christian evangelical beliefs shading rapidly into something more like of shamanism (‘Mum’s Snake’ and ‘Divine Healing’). It may be superstition that prevents the mother wanting to be photographed but her absence from the family album is a good metaphor for her selfless devotion to her family’s wellbeing, perhaps to the unseen presence of black women in society more generally.

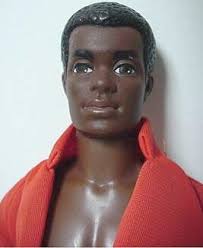

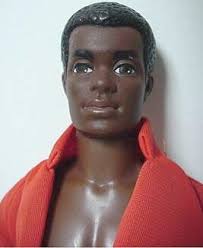

Though the recurring father figure is said to be not “of our land”, it’s hard to identify any explicitly white voice in this collection; the black or mixed-race voices are so by implication. Long sees no need to labour the point. The one explicitly white voice I can find is that of a Barbie doll. This poem (‘Interview with B. tape II’) and its companion piece ‘steve’, mark a shift in perspective to a voice that does read the world in black and white. Long puts her ventriloquism to disturbing effect as she makes white-skinned Barbie talk about her stereotypical love/submissiveness to Ken and the way the arrival of a black-skinned doll, Steve, upsets things:

Steve wore bright red swim shorts. Too bright.

Everything about those people is so . . .

You know?

The racism is casually thrown off; crime in the area goes up with Steve’s arrival. Ken takes on the vigilante role, beating Steve up in the back of his army jeep. This is a clever and skilful poem – the racist attitudes in the child’s doll’s mouth are very disturbing. ‘steve’ uses the child’s narrative voice we’ve become familiar with throughout the book but the racist, hatred of the steve doll is now internalised and comes from the child herself; “ken would beat steve up / for fun”. The violence of the earlier poem is now played out in toyland (but no less real for that) so that, one day, the father finds his lawnmower jammed: “on closer inspection / a tiny pair of shorts charred / torso”. In this year of the death of George Floyd and the shooting of Jacob Blake, Rachel Long finds unexpectedly effective ways to address the issues of racial discrimination alongside her main concerns in this never less than accessible collection.

The racism is casually thrown off; crime in the area goes up with Steve’s arrival. Ken takes on the vigilante role, beating Steve up in the back of his army jeep. This is a clever and skilful poem – the racist attitudes in the child’s doll’s mouth are very disturbing. ‘steve’ uses the child’s narrative voice we’ve become familiar with throughout the book but the racist, hatred of the steve doll is now internalised and comes from the child herself; “ken would beat steve up / for fun”. The violence of the earlier poem is now played out in toyland (but no less real for that) so that, one day, the father finds his lawnmower jammed: “on closer inspection / a tiny pair of shorts charred / torso”. In this year of the death of George Floyd and the shooting of Jacob Blake, Rachel Long finds unexpectedly effective ways to address the issues of racial discrimination alongside her main concerns in this never less than accessible collection.

Robert Selby’s debut collection is fronted by a wood cut engraving by Clare Leighton, titled ‘Planting Trees’. Two flat-capped workmen labour to bed in a sapling. A wind-bent tree stands nearby; on the gusty skyline, at the top of a hill, a dark copse. It’s like something out of a Thomas Hardy poem, or an Edward Thomas one, and it’s well-chosen as these are the forebears The Coming-Down Time often explicitly acknowledges. Launched into a poetry world dominated by so many books addressing environmental, gender, race and identity issues, this collection (depending on your viewpoint) is either timeless or behind the times. Selby’s careful organisation of the poems makes it clear he knows what he’s doing and he will do it his way.

Robert Selby’s debut collection is fronted by a wood cut engraving by Clare Leighton, titled ‘Planting Trees’. Two flat-capped workmen labour to bed in a sapling. A wind-bent tree stands nearby; on the gusty skyline, at the top of a hill, a dark copse. It’s like something out of a Thomas Hardy poem, or an Edward Thomas one, and it’s well-chosen as these are the forebears The Coming-Down Time often explicitly acknowledges. Launched into a poetry world dominated by so many books addressing environmental, gender, race and identity issues, this collection (depending on your viewpoint) is either timeless or behind the times. Selby’s careful organisation of the poems makes it clear he knows what he’s doing and he will do it his way.

Selby’s use of language and form is likewise pretty traditional. It’s not just a result of the subject matter that the book is frequented by words such as smithy, shire, lambkin, deer-stalker, and lush-toned phrases such as “blossom-moted”. The flip side of this is that details of 2020 UK are often treated with a distaste, an alienated distance. Later in the book, a friend returns from the dust and pollen of the English countryside into London: “its tagged shutters and sick-flecked stops, / its scaffolding like the lies / propping up your peeling hopes”. The friend is female and (I think) Canadian. Another poem’s narrator tries to persuade her that “[t]his is the real England [. . .] It’s a place of trees; of apple, pear, cherry and plum”. There is more to be said here about the meaning of ‘real’ and it’s hard to tell if the narrator’s invitation is meant to have a deathly ring to it. He asks, “Do you want to reset your watch to the toll of here?”

Selby’s use of language and form is likewise pretty traditional. It’s not just a result of the subject matter that the book is frequented by words such as smithy, shire, lambkin, deer-stalker, and lush-toned phrases such as “blossom-moted”. The flip side of this is that details of 2020 UK are often treated with a distaste, an alienated distance. Later in the book, a friend returns from the dust and pollen of the English countryside into London: “its tagged shutters and sick-flecked stops, / its scaffolding like the lies / propping up your peeling hopes”. The friend is female and (I think) Canadian. Another poem’s narrator tries to persuade her that “[t]his is the real England [. . .] It’s a place of trees; of apple, pear, cherry and plum”. There is more to be said here about the meaning of ‘real’ and it’s hard to tell if the narrator’s invitation is meant to have a deathly ring to it. He asks, “Do you want to reset your watch to the toll of here?” The import of this question forms the emotional and dramatic context of the later poems in the collection which trace an on/off relationship. The narrator is left wondering: “I must wait for the needle / of your heart’s compass to unspin, / and see where it stops”. In reading that I’m reminded of Lea and – what seemed to be – her relative lack of choice in the earlier years of the twentieth century. There is a good deal of unalloyed nostalgia in The Coming-Down Time for an England of the mind, if it was ever part of any actual century. I find the female figures in the book suffer because of this: most of them do not achieve a specific, particular life in the poems. I’d like Selby to go on to explore the irony in two images: the masculine arms in “rolled up sleeves” that may or may not be “strong enough” and the closing lines just quoted, in which the desired woman bides her time, knowingly possessed of strength, of the agency of decision.

The import of this question forms the emotional and dramatic context of the later poems in the collection which trace an on/off relationship. The narrator is left wondering: “I must wait for the needle / of your heart’s compass to unspin, / and see where it stops”. In reading that I’m reminded of Lea and – what seemed to be – her relative lack of choice in the earlier years of the twentieth century. There is a good deal of unalloyed nostalgia in The Coming-Down Time for an England of the mind, if it was ever part of any actual century. I find the female figures in the book suffer because of this: most of them do not achieve a specific, particular life in the poems. I’d like Selby to go on to explore the irony in two images: the masculine arms in “rolled up sleeves” that may or may not be “strong enough” and the closing lines just quoted, in which the desired woman bides her time, knowingly possessed of strength, of the agency of decision.