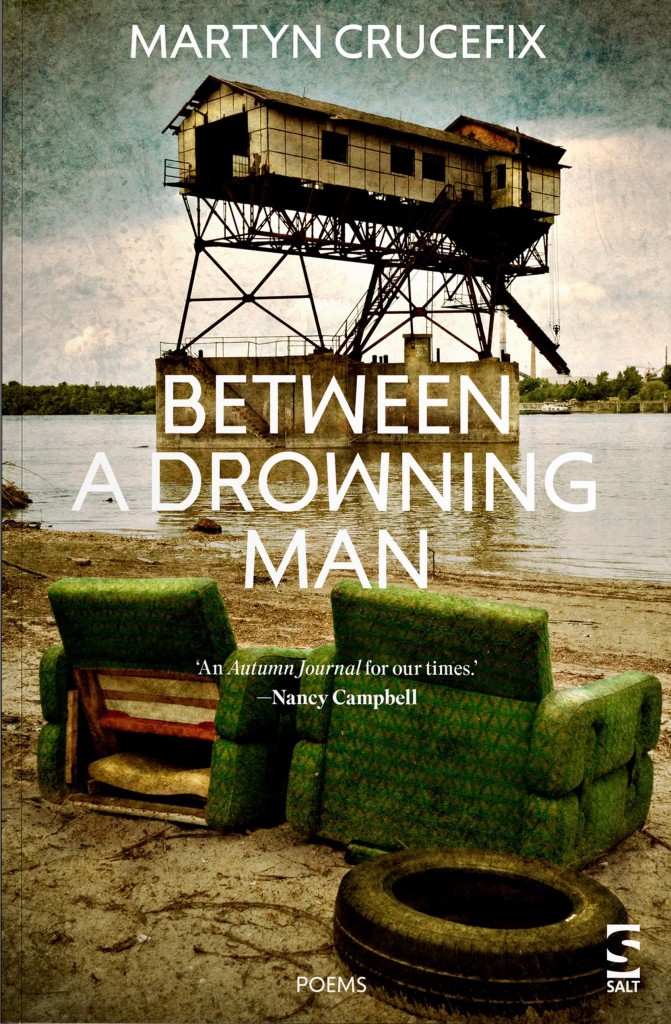

Here is Ian Brinton‘s recent review of my new Salt collection, Between a Drowning Man. It was first published by Litter Magazine in January 2024.

The invitation at the opening of these two remarkable sequences of poems by Martyn Crucefix emphasises both ‘difference’ and ‘ambiguity’, an ‘othering’ which hones attention rather than dulling it.

Divided into two sections, Works and Days (forty-nine poems) and O, at the Edge of the Gorge (fourteen poems) the two landscapes bring into focus a post-2016 Britain and the countryside of the Marche in central, eastern Italy. The leitmotif which threads its pathway, its recurring echo, through the first section is of ‘all the bridges’ being ‘down’ and the epigraph to section two is a quotation from Canto 16 of Dante’s Paradiso in which cities pass out of existence through warfare or disease and that which may have seemed permanent is continuously in movement. That second section of poems is a sequence of sonnets and in the final one the hawk’s resting place in the ‘shivering of poplars’ sways so that he is neither falling nor at ease

with these thinnest of airs beneath him

these shapes of loose knotted mesh

these whisperings that cradle him on a whim

That ‘othering’ prompts the poet to see the differences that are ‘like crimes woven into the weft’ and, in a way that William Blake would have recognised in his ‘A Poison Tree’, envy can be ‘buried long years in the black heart / of expressed admiration’ and ‘sunshine’ can be ‘really the withering of night’ which is ‘poured into soil where wheat grows’. And so it is—‘in and around and over and above’ because ‘all the bridges are down’.

In April 2007 Jeremy Prynne wrote some notes for students about poems and translation:

Translation is for sure a noble art, making bridges for readers who want to cross the divide between their own culture and those cultures which are situated in other parts of the world; and yet a material bridge is passive and inert, without any life of its own, whereas a poetic translator must try to make a living construction with its own energy and powers of expression, to convey the active experience of a foreign original text.

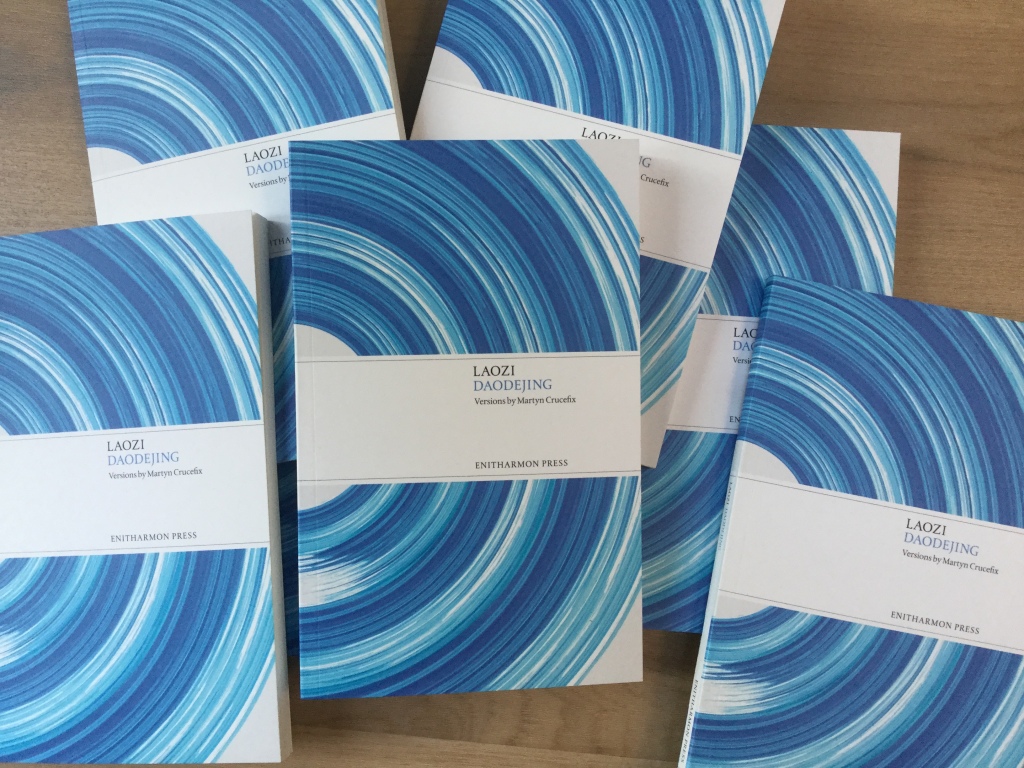

As a translator of real distinction (Rilke’s Duino Elegies and The Sonnets to Orpheus) Crucefix has for many years made these living constructions offering readers a gateway into new experiences whether it be through the world of Laozi’s Daodejing (Enitharmon Press, 2016) or through these new poems which offer echoes both of Hesiod’s Work and Days and the poems known as a vacanna which originated in the bhakti religious protest movements in 10-12th century India. His understanding of the central role language plays in our lives, that creation of bridges between humans, was one of the deeply moving and memorable moments in his collection from Seren in 2017, The Lovely Disciplines. There the poem ‘Words and things’ presented an elderly individual who discovered ‘too late this absence of words’ which now ‘builds a prison’ and Crucefix recognised that ‘a man without language is no man’: as the world of objects becomes too difficult to dominate he can only have knowledge of a world which ‘turns in your loosening grip’. The echo of Yeats’s ‘The Second Coming’ is surely no accidental one!

Translations are bridges, language is a bridge, and the distressing recognition of isolation within numbers is the dominant image in ‘fifteen kilometres of traffic’ from the first section of this new book:

fifteen kilometres of traffic wait before us

behind us the infinite tail

x

we are offered Google Map options

yet those trumpeted ten minute economies

x

are nothing till they can be proved

you make a choice you go your own way –

x

this has been better said before of course –

you cannot take the other way

x

and remain a unitary being on two paths

or perhaps sane – all roads crawl north

x

because multiple millions of cars crawl north

because all the bridges are down

Those ten minute trumpetings bring the world of Orwell’s 1984 to my mind as loud announcements of positive news seem to possess a tinny emptiness to the understanding of the isolated human who exists in a world of no bridges.

However, in contrast to this wave of uniformity one reads moments of ‘othering’ in the second section of this book as in ‘sharpening gusts along the valley floor’ a scrap of air was birthed

whirling inches above a littered drain

in a back street of some hilltop town

x

like Urbisaglia or some place that has seen

and has survived change of use

from sacred temple to church to slaughterhouse

and no gully nor hill can stop it

In this moving world ‘great swathes of air’ gather strength to flex ‘all things to a scurrying to keep up / and the truth is some will and some will fail’.

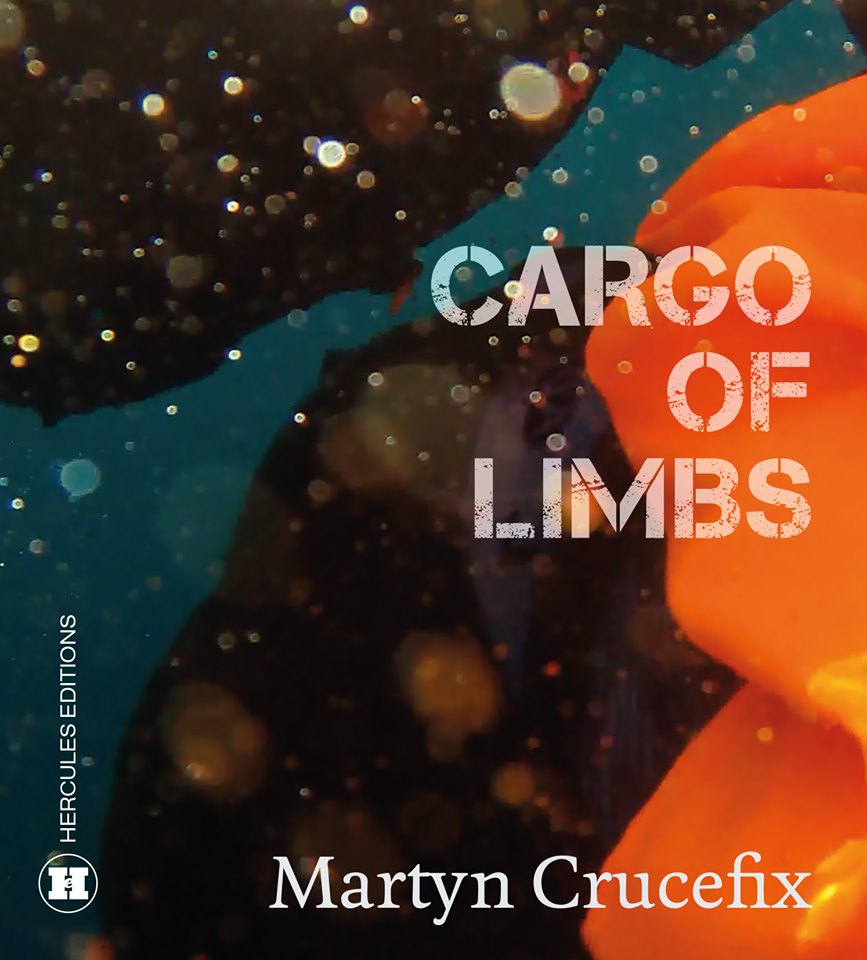

In a poem titled ‘can you imagine’ (for my children) from the first section of Between a Drowning Man the power of language to translate the invisible onto the page is presented with an unerring eye focussed upon reality. In a world in which he no longer shares the companionship of others the poet is carried safely because although ‘you find the bridges between us fallen down’ and although ‘you mourn’ you can still ‘imagine’. That sense of continuity held in the imagination is far from the image of Alan Kurdi, the three-year-old Syrian boy drowned on the beach near Bodrum, Turkey, in 2015 whose death was recorded by Crucefix’s earlier book, Cargo of Limbs, from Hercules Editions in 2019. The boy’s family had fled from the war engulfing Syria in the hope of joining relatives in the safety of Canada and became ‘part of the historic movement of refugees from the Middle East to Europe at that time’:

In the early hours of September 2nd, the family crowded onto a small inflatable boat on a Turkish beach. After only a few minutes, the dinghy capsized. Alan, his older brother, Ghalib, and his mother, Rihanna, were all drowned. They joined more than 3,600 other refugees who died in the eastern Mediterranean that year.

In this new book that ‘whim’ of a resting place for the hawk, those ‘whisperings’ prompt the bird, the poet, ‘to call it yet more steady perhaps’:

this whim—this wish—this risky flight

in the fleeting black wake of the carpenter bees

Chen Xianfa is a prize-winning poet and journalist, born in Anhui Province, China. He has published five books of poems: Death in the Spring (1994), Past Life (2005), Engraving the Tombstone (2011), On Raising Cranes (2015; in English tr. 2017) and Poems in Nines (2018; bilingual Chinese/English, tr. Nancy Feng Liang, publ. China) which was awarded the Lu Xun Prize. A Selected Poems appeared in 2019. He has published two collections of essays, Heichiba Notes (2014 and 2021). Other awards include China’s Top Ten Influential Poets (1998-2008), the Hainan Biennial Poetry Prize (2011), Yuan Kejia Poetry Prize (2013), Tian Wen Poetry Prize (2015) and the Chenzi’ang Poetry Prize (2016).

Chen Xianfa is a prize-winning poet and journalist, born in Anhui Province, China. He has published five books of poems: Death in the Spring (1994), Past Life (2005), Engraving the Tombstone (2011), On Raising Cranes (2015; in English tr. 2017) and Poems in Nines (2018; bilingual Chinese/English, tr. Nancy Feng Liang, publ. China) which was awarded the Lu Xun Prize. A Selected Poems appeared in 2019. He has published two collections of essays, Heichiba Notes (2014 and 2021). Other awards include China’s Top Ten Influential Poets (1998-2008), the Hainan Biennial Poetry Prize (2011), Yuan Kejia Poetry Prize (2013), Tian Wen Poetry Prize (2015) and the Chenzi’ang Poetry Prize (2016).

Nina Mingya Powles’ collection, Magnolia 木蘭, is an uneven book of great energy, of striking originality, but also of a great deal of borrowing. This is what good debut collections used to be like! I’m reminded of Glyn Maxwell’s disarming observation in On Poetry (Oberon Books, 2012) that he “had absolutely nothing to say till [he] was about thirty-four”. The originality of Magnolia 木蘭 is largely derived from Powles’ background and brief biographical journey. She is of mixed Malaysian-Chinese heritage, born and raised in New Zealand, spending a couple of years as a student in Shanghai and now living in the UK. Her subjects are language/s, exile and displacement, cultural loss/assimilation and identity. Shanghai is the setting for most of the poems here and behind them all loiter the shadows and models of

Nina Mingya Powles’ collection, Magnolia 木蘭, is an uneven book of great energy, of striking originality, but also of a great deal of borrowing. This is what good debut collections used to be like! I’m reminded of Glyn Maxwell’s disarming observation in On Poetry (Oberon Books, 2012) that he “had absolutely nothing to say till [he] was about thirty-four”. The originality of Magnolia 木蘭 is largely derived from Powles’ background and brief biographical journey. She is of mixed Malaysian-Chinese heritage, born and raised in New Zealand, spending a couple of years as a student in Shanghai and now living in the UK. Her subjects are language/s, exile and displacement, cultural loss/assimilation and identity. Shanghai is the setting for most of the poems here and behind them all loiter the shadows and models of

I don’t think the intriguing glimpses of an individual young woman in this first poem are much developed in later ones. The Mulan figure makes a couple of other appearances in the book and is reprised in the concluding poem, ‘Magnolia, jade orchid, she-wolf’. This consists of even shorter prose observations. In Chinese, ‘mulan’ means magnolia so the fragments here cover the plant family Magnoliaceae, the film again, the Chinese characters for mulan, Shanghai moments, school days back in New Zealand and Adeline Yen Mah’s Chinese Cinderella. It’s hard not to think you are reading much the same poem, using similar techniques, though this one ends more strongly: “My mouth a river in full bloom”.

I don’t think the intriguing glimpses of an individual young woman in this first poem are much developed in later ones. The Mulan figure makes a couple of other appearances in the book and is reprised in the concluding poem, ‘Magnolia, jade orchid, she-wolf’. This consists of even shorter prose observations. In Chinese, ‘mulan’ means magnolia so the fragments here cover the plant family Magnoliaceae, the film again, the Chinese characters for mulan, Shanghai moments, school days back in New Zealand and Adeline Yen Mah’s Chinese Cinderella. It’s hard not to think you are reading much the same poem, using similar techniques, though this one ends more strongly: “My mouth a river in full bloom”. Unlike Carson’s use of fragmentary texts, Powles is less convincing and often gives the impression of casting around for links. This is intended to reflect a sense of rootlessness (cultural, racial, personal) but there is a willed quality to the composition. One of the things Powles does have to say (thinking again of Maxwell’s observation) is the doubting of what is dream and what is real. The prose piece, ‘Miyazaki bloom’, opens with this idea and the narrator’s sense of belonging “nowhere” is repeated. This is undoubtedly heartfelt – though students living in strange cities have often felt the same way. Powles also casts around for role models (beyond Mulan) and writes about the New Zealand poet, Robin Hyde and the great Chinese author Eileen Chang, both of whom resided in Shanghai for a time. ‘Falling City’ is a rather exhausting 32 section prose exploration of Chang’s residence, mixing academic observations, personal reminiscence and moments of fantasy to end (bathetically) with inspiration for Powles: “I sit down at one of the café tables and begin to write. It is the first day of spring”.

Unlike Carson’s use of fragmentary texts, Powles is less convincing and often gives the impression of casting around for links. This is intended to reflect a sense of rootlessness (cultural, racial, personal) but there is a willed quality to the composition. One of the things Powles does have to say (thinking again of Maxwell’s observation) is the doubting of what is dream and what is real. The prose piece, ‘Miyazaki bloom’, opens with this idea and the narrator’s sense of belonging “nowhere” is repeated. This is undoubtedly heartfelt – though students living in strange cities have often felt the same way. Powles also casts around for role models (beyond Mulan) and writes about the New Zealand poet, Robin Hyde and the great Chinese author Eileen Chang, both of whom resided in Shanghai for a time. ‘Falling City’ is a rather exhausting 32 section prose exploration of Chang’s residence, mixing academic observations, personal reminiscence and moments of fantasy to end (bathetically) with inspiration for Powles: “I sit down at one of the café tables and begin to write. It is the first day of spring”.

One day around 1973/4, Ted Hughes bought or was given

One day around 1973/4, Ted Hughes bought or was given

Ted Hughes began by modelling poems of his own closely on the work of the poet that Ramanujan places first in the collection, the 12th century Indian poet-saint, Basavanna. Early on Hughes adheres closely to the originals but gradually he distances himself, starting to create more original poems, often employing personal materials, and (as I have said) some of these little poems eventually found their way into the final section of Gaudete. The refrain and invocation that Basavanna uses in the majority of his poems is the address to Siva as “lord of the meeting rivers”. The influence of Robert Graves’ The White Goddess is well known on Hughes and he decided to experiment with addressing his own conception of the divinity – a female divinity – at once his muse and the fundamental animating force in the world, as “Lady of the Hill”.

Ted Hughes began by modelling poems of his own closely on the work of the poet that Ramanujan places first in the collection, the 12th century Indian poet-saint, Basavanna. Early on Hughes adheres closely to the originals but gradually he distances himself, starting to create more original poems, often employing personal materials, and (as I have said) some of these little poems eventually found their way into the final section of Gaudete. The refrain and invocation that Basavanna uses in the majority of his poems is the address to Siva as “lord of the meeting rivers”. The influence of Robert Graves’ The White Goddess is well known on Hughes and he decided to experiment with addressing his own conception of the divinity – a female divinity – at once his muse and the fundamental animating force in the world, as “Lady of the Hill”. But as in the best poetry, such simplicity of language and tone belies the spiritual intentions of the originals and of Hughes’ experimental vacana poems too. As Ann Skea explains, in his turn, Hughes “becomes the spiritual bridegroom of the Lady of the Hill and struggles to be worthy of that union”. Unlike the original Indian poems, Hughes seems to see his Goddess in every human female and they are seen as testing and challenging the poet to further spiritual growth. In the end, just 18 of these experimental poems were chosen to form the Epilogue to Gaudete as the songs sung by the Reverend Nicholas Lumb on his return from the underworld: a man who had seen things and felt the need to communicate those things: “he saw the notebook again, lying on the table, and he remembered the otter and the strange way it had come up out of the lough because a man had whistled. He opened the notebook and began to decipher the words, he found a pen and clean paper and began to copy out the verses”.

But as in the best poetry, such simplicity of language and tone belies the spiritual intentions of the originals and of Hughes’ experimental vacana poems too. As Ann Skea explains, in his turn, Hughes “becomes the spiritual bridegroom of the Lady of the Hill and struggles to be worthy of that union”. Unlike the original Indian poems, Hughes seems to see his Goddess in every human female and they are seen as testing and challenging the poet to further spiritual growth. In the end, just 18 of these experimental poems were chosen to form the Epilogue to Gaudete as the songs sung by the Reverend Nicholas Lumb on his return from the underworld: a man who had seen things and felt the need to communicate those things: “he saw the notebook again, lying on the table, and he remembered the otter and the strange way it had come up out of the lough because a man had whistled. He opened the notebook and began to decipher the words, he found a pen and clean paper and began to copy out the verses”.

The poems move from one image to the next but there are the same preoccupations – the specks and the flocks and movements alongside monuments and geology – contrasting contexts of time, and the sense (especially given the form) of something trying to be ordered or sorted out, but not quite complying – “dicing segments of counted time…” The diagrammatic, map-like – but not-quite scrutable imagery is a response to this – an attempt to make sense of forms and information, or grasp a particular memory and note it down. Not quite successfully. We are left with a string of related thoughts and a measuring or structuring impulse.

The poems move from one image to the next but there are the same preoccupations – the specks and the flocks and movements alongside monuments and geology – contrasting contexts of time, and the sense (especially given the form) of something trying to be ordered or sorted out, but not quite complying – “dicing segments of counted time…” The diagrammatic, map-like – but not-quite scrutable imagery is a response to this – an attempt to make sense of forms and information, or grasp a particular memory and note it down. Not quite successfully. We are left with a string of related thoughts and a measuring or structuring impulse.