I have recently posted about Robert Frost’s brief essay ‘The Figure a Poem Makes’ as well as on one of his lesser known poems, ‘A Soldier’. The latter is one of the poems I’ll be teaching this coming academic year as set by the Cambridge International Exam Board: see page 47. Student essays are supposed to offer a close analysis of one (or two poems) while also exploring a wider understanding of what the poet is doing in terms of methods and concerns (techniques and themes). Another of the set poems is discussed in what follows: ‘Two Look at Two’. I read the poem here:

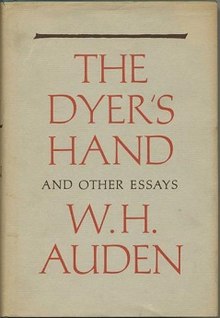

In The Dyer’s Hand (1963), Auden’s essay on Frost opens by observing that, if asked who said ‘Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty’, most people would reply ‘John Keats’. Auden differs, arguing the famous phrase is really something Keats makes the Grecian urn say so the author maintains some dramatic distance between himself and the poem’s questionable statement. This is also a very Frostian device – though not one that Auden probes in his subsequent discussion of the poems. Whenever we read Frost, it’s important to be alert to such ironic distancing from the (simply understood) lyric voice or ‘I’. In fact, ‘Two Look at Two’ is a poem which does not obviously lend itself to this ‘dramatic’ sort of interpretation as its narrative voice seems more reliably omniscient, or at least impersonal. And yet the obvious meaning of the poem is not characteristic of a poet whose work can be dark and pessimistic, indeed labelled “terrifying” by Lionel Trilling in 1959. In the poem, a couple of lovers, walking up a mountain, encounter a corresponding pair of deer – a doe and buck. At the end of the brief, uneventful encounter the narrator reports that the human couple sense a “wave” of reciprocated love emanating from the “earth”. At the conclusion of this discussion, I’ll look again at whether the narrator’s confident assertion of this should be taken at face value.

The first and last words in the poem are the same: “love”. The opening 3 lines are full of qualifying equivocations with the choice of verb form “might” and the vague but limiting phrases about how far up the mountain side the couple will go: “A little further up” and “not much further up”. It is the twin forces of “love and forgetting” which have the potential to drive them higher up the mountain. The two are probably linked in that, absorbed in their mutual love, they may become forgetful, neglectful of the potential dangers in the landscape. The risk of self-absorption (even in the cause of romantic love) is raised here by Frost, a risk encountered by other narrators in poems like ‘An Encounter’, ‘The Wood-Pile’ and most clearly in ‘Stopping by Woods…’ In the latter, the allure of the snowy woods is strongly felt by the narrator (“The woods are lovely, dark, and deep”) but his work and social responsibilities probably prevent him from abandoning the road and risking/welcoming death by exposure.

In many cases, the chief risk is a neglect of the boundaries that in Frost’s world it seems wiser to acknowledge and adhere to. In ‘Two Look at Two’ this is clear in the forceful verbs used in the following few lines (“They must have halted” and “they must not go”) and it may explain the optimistic nature of this poem that we see the lovers in fact do adhere to the limits set. Lines 5/6 suggest they have thoughts not of over-reaching or dizzying aspiration but rather of the dangers present to them: “With thoughts of the path back, how rough it was / With rock and washout, and unsafe in darkness”. Frost’s music here is suitably rough and threatening with its harsh consonants and internal rhyme (path/back), the growling ‘r’ sounds followed by a swilling of sibilance (washout /unsafe /darkness) suggestive of the water-eroded path on the hillside. When they encounter the actual physical barrier of a wall, Frost bulks it up (despite its ruined state) in the reader’s ear with heavy plosive ‘b’ sounds: “they were halted by a tumbled wall / With barbed-wire binding”.

This is not a barrier to be passed easily – and the lovers do not even try. They possess a sort of Frostian piety or reverence most clearly seen also in ‘Mending Wall with its repeated maxim: “Good fences make good neighbours”. ‘Two Look at Two’ does allow its lovers a residual “onward impulse” which they spend, or expend, simply by gazing up along the path “they must not” now follow. The dangers that lie there are again described with a telling adjective (it is a “failing path”) and a haunting moment of hypothetical personification: “if a stone / Or earthslide moved at night, it moved itself”. It is at this point that we hear some words spoken by the lovers. Their words are brief and (effectively) firmly monosyllabic – “This is all [. . . ] Good-night to woods”. But they are accompanied by a sighing of regret that the walk has reached its limit. Frost here is accepting the reality of human desire – that “limitless trait of ‘There Are Roughly Zones’ –but he and the lovers see the risks of its limitless pursuit.

The lovers’ clipped statements are answered in kind by the narrative voice: “But not so; there was more.” The clipped, heavily punctuated nature of lines 13/14 make them a clear, early turning point in the poem, a moment of stasis and some tension. The unpunctuated and enjambed line 15 then sets the narrative flowing again as it records the sudden presence of the doe, staring back across the wall at the lovers. The mirroring effect is most important and presented through the plain language of lines 16/7: the doe is looking at them “Across the wall, as near the wall as they. / She saw them in their field, they her in hers”. In each line the caesura acts as the wall, dividing and join the two halves of the lines. The repetitions of ‘wall’, ‘they’, ‘their’ and ‘her’ slow and focus the reader on what the title suggests is the mutual regard occurring on either side of the wall.

Frost’s narrative slides seamlessly into the doe’s perspective, imagining her difficulty in seeing the couple. Though watched carefully, their alien appearance is conveyed in a simile: they are “like some up-ended boulder split in two”. But the couple perceive no “fear” in the creature and Frost’s formulation – “they saw no fear there” – also suggests they feel no fear on their part either. In fact, lines 21-24 rather suggest the couple, “though strange”, do not possess much interest for the doe:

She could not trouble her mind with [them] too long,

She sighed and passed unscared along the wall.

Notably, she also shares the ‘sigh’ with the couple and in this way the shared mutuality of the encounter is emphasised, preparing us for the final affirmative moments of the poem.

The couple’s speech (line 25) suggests – through italicisation, short phrases and the rhetorical question – that they are breathlessly impressed. They think this is “all” but there is more to come. Frost’s poem ‘The Most of It’ comes to mind, recording as it does the appearance of another creature (“As a great buck”), its advent perhaps a response to a man’s demand for “counter-love, original response”. There, the creature seems brutish, indifferent, unaware, alien and incomprehensible as it stumbles off into the underbrush. ‘The Most of It’ (bafflingly not a poem included in CIE’s set poem list) is a key poem to contrast with ‘Two Look at Two’. In the latter, a buck also appears and, despite its more challenging even arrogant tone, it is never as frighteningly remote as the creature in ‘The Most of It’.

The buck of ‘Two Look at Two’ announces itself with a “snort” and is a more stereotypically masculine presence with its antlers, “lusty nostril”, its jerking head and its (imagined) arrogantly dismissive questioning of the couple. But his difference from the doe is minor as we recognise a whole line repeated: the buck also stands looking at the couple, “Across the wall, as near the wall as they”. It’s perhaps not clear who is interpreting the shaking of the buck’s head as questions. It’s either the narrative voice itself or that voice reporting (omnisciently) on the thoughts of the couple. His questions verge on the belligerent:

Why don’t you make some motion?

Or give some sign of life? Because you can’t.

I doubt if you’re as living as you look.

If we are going to find disharmony in this seemingly mutual encounter, this is where it might lie. The buck’s questions portray the couple as standing respectfully, perhaps in awe, certainly in silence. The impact of the (imagined) questions is to make the human couple “almost” feel “dared / to stretch a proffering hand – and a spell-breaking one”. So the buck’s obstreperous attitude strikes the couple as a dare to reach out across the divide. Such an action would be to proffer, “to hold out or put forward (something) to someone for its acceptance”, hence a gesture of friendship. But Frost also makes it clear such a reaching across the divide would break the spell of mutual regard which has been the subject of the whole poem. In fact, the moment of choice – a topic of so many other Frost poems, most famously ‘The Road Not Taken’ – is passed over as the buck, just like the doe, moves away, “unscared along the wall”.

The final 5 lines deal with the impact on the lovers. Again, they briefly speak: “This must be all”. And on this occasion, the narrative voice agrees: “It was all”. The final phrase in ‘The Most of It’ is “and that was all”. Is this the cry or half-question of the disappointed man asking, ‘Is there no more than this’? Or is it a rapt, stunned whispering in the face of a vision of a unitary world declaring, ‘So this is all and all’s connected’? You could ask the same questions about the end of ‘Two Look at Two’ though the couple’s italicised emphasis in line 39 and the fact they continue to stand, as if rapt and wrapped still in the experience they have just had, surely does not suggest disappointment. Frost uses the metaphor of the “wave” sweeping over them, suggesting an irresistible inundation, a largeness of feeling derived from this minor incident. It is “As if the earth in one unlooked-for favour / Had made them certain earth returned their love”.

But the “As if” that opens line 41 cannot be ignored. This is how it felt – for the lovers. I don’t think Frost wants to deny them their experience. But perhaps they are still too absorbed in their own “Love and forgetting”. This is where the sense of the poem as a dramatic performance perhaps is relevant, in this case the incident rosily-coloured by the perceptions of the lovers. We ought to hesitate before we conclude that Frost himself sees the earth as in fact mutually responding with love. This would be exactly the “counter-love, original response” that so signally does not occur in ‘The Most of It’. The optimism of ‘Two Look at Two’ cannot be dismissed – but nor can it be taken in any simple way as the real and final ‘message’ of its author.