As a Royal Literary Fund Fellow based at The British Library in London (though working on-line for the most part), I was asked way back in May 2020 (feels like a different world) to write and record three brief talks. One of these was on ‘Writing and Technology’ which I posted (as text and audio file) on this blog a few months ago. Another commision was to be titled ‘How I Write’ – not an easy subject on which to be clear and succinct but with a little help from WH Auden and Louise Gluck I hope I managed to say something that might be of help to all kinds of writers – poets, novelists and (the target audience of the RLF project) those writing at the varied levels of academe.You can read my blog (and hear me read the essay) here. The third and final essay was an intriguing invitation to write a ‘Letter to My Younger Self’. The recording of that piece has now been released and is available as an audio file on the RLF’s VOX site. You can read the Letter below – or listen to me read it by clicking here – or both at the same time if you’d like. Afterwards I have also posted a poem relevant to that particular biographical moment. An earlier version of this poem first appeared, a long while back, in The London Magazine.

Letter to my Younger Self

Dear Martyn,

You will have just got off the train from London Bridge. It’s 1976. The end of a day studying Medicine which you begin to hate. And now back to Eltham Park, to digs you’ve loathed since you arrived (the well-meaning landlady is no substitute for your mother). Probably you walked past that little music shop somewhere near the station, spending minutes gazing at the red sunburst acoustic guitar in the window. If it doesn’t sound too weird, I can tell you – you’ll buy it and strum on it for 10 years or more. I can also confirm your fear: you fail your first-year exams. The Medical School allows you to leave . . . But listen, that sense of failure and lostness, it will pass.

Keep on with the music, though your playing is not up to much and your singing . . . well, the less said. But writing songs will eventually lead somewhere. And the illicit books! You are supposed to be reading the monumental Gray’s Anatomy, textbooks on Pharmacology, Biochemistry, all emptying like sand out of your head. You’ve yet to go into that charity shop and pick up a book called The Manifold and the One by Agnes Arber. You’ll be attracted by the philosophical-sounding title; in your growing unhappiness at Medical School you have a sense of becoming deep. The questions you ask don’t have easy answers. You have a notion this is called philosophy. Amidst the dissections, test tubes and bunsens, you’ll find consolation in Arber’s idea that life is an imperfect struggle of “the awry and the fragmentary”.

And those mawkish song lyrics you are writing? They will become more dense, exchanging singer-songwriting clichés for clichés you clumsily pick up from reading Wordsworth (you love the countryside), Sartre’s Nausea (you know you’re depressed) and Allan Watts’ The Wisdom of Insecurity (you are unsure of who you are). Up ahead, you take a year out to study English A level at an FE College. Your newly chosen philosophy degree gradually morphs into a literature one and with a good dose of Sartrean self-creativity (life being malleable, existence rather than essence) you edit the university’s poetry magazine, write stories, write plays, even act a little (fallen amongst theatricals!).

At some point, the English Romantic writers get a grip on you, taking you to Oxford where you really do conceive of yourself as a poet, get something published, hang out with others who want the same. Then guess what – for a teenager who’d so little to say for himself in class – teaching becomes a way of continuing to study and write while making a living. It suits. It takes us out of ourselves.

Along the way, you write some poems you are proud of. You will suffer the writer’s curse, of course: the recurrent fear of not being able to turn the trick again. But I’m sending you this to say, through all the years ahead, it is words that will infinitely enrich your life. So pick up the pad you doodle on in lectures. Write a line. Write another line. I see you hunched over a dim-lit desk, but no question – yes – you are heading in my direction.

With best wishes,

Martyn

x

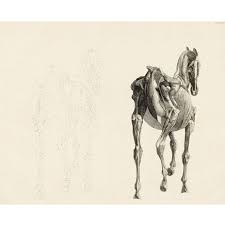

How to fail at anatomy

x

This one believed

he maybe had the brains

another that he had

the right demeanour

x

but the Schools denied him

till it was too late

then reprieved him

with the offer of a place

x

that by then he knew

could not be refused

(such anticipation

had struck such roots)

x

so he has no recall

of the moment of choice

before those appalling

digs in Eltham

x

where he had to stow

his dislocated skeleton

under the bed—crammed

one side of his head

x

with tendons muscles

and pharmacol

with biochem and

bright sets of nerves

x

everything spilling out

the other side

into failure—fallen

to wandering streets

x

to stealing Everyman’s

Selected Wordsworth

he was John Stuart Mill

wishing his soul

x

saved though he felt

love etiolating

the girl from home

now a girl from home

x

her kisses like shrugs

at London Bridge

saying go your own way

at least not imposed

x

not merely allowed

and if you want to live

deliberately first

you slit the shroud

It may be that this ability to be sustained by scraps and glimpses, the sense that the self is most fully resolved in a lack of egotism, in its encounter with ordinary things, can diminish some of the sting of mortality. In a poem like ‘White’, MacRae manages to celebrate again the ordinariness of familiar things while at the same time sustaining a contentedness (or at least an absence of fear) at the prospect of the self’s vanishing: “You can disappear in a house where / you feel at home; the rooms are spaces / for day-dreams, maps of an interior / turned inside out”. Rather than Macbeth, it is Hamlet’s resolve to “let be” that comes to mind as this calm, accessible, colourful and wonderfully dignified poem concludes:

It may be that this ability to be sustained by scraps and glimpses, the sense that the self is most fully resolved in a lack of egotism, in its encounter with ordinary things, can diminish some of the sting of mortality. In a poem like ‘White’, MacRae manages to celebrate again the ordinariness of familiar things while at the same time sustaining a contentedness (or at least an absence of fear) at the prospect of the self’s vanishing: “You can disappear in a house where / you feel at home; the rooms are spaces / for day-dreams, maps of an interior / turned inside out”. Rather than Macbeth, it is Hamlet’s resolve to “let be” that comes to mind as this calm, accessible, colourful and wonderfully dignified poem concludes: For MacRae’s interest in and skill with poetic form, we need look no further than the extraordinary glose on a quatrain from Alice Oswald (the earlier collection contained another on lines from Mary Oliver). For most poets, this form is little more than an exhibitionist high-wire act, but MacRae’s poems are moving and complete. Her use of poetic form here, particularly in some of these last poems, reminds me of Tony Harrison’s conviction that its containment “is like a life-support system. It means I feel I can go closer to the fire, deeper into the darkness . . . I know I have this rhythm to carry me to the other side” (Tony Harrison: Critical Anthology, ed. Astley, Bloodaxe Books, 1991, p.43). Appropriately, in ‘Jar’, she contemplates with admiration an object that has “gone through fire, / risen from ashes and bone-shards / to float, nameless, into our air”. Here, the narrator movingly lays aside the wary scepticism of the Thomas epigraph and rests her cheek on the jar’s warmth to “feel its gravity-pull / as if it proved the afterlife of things”.

For MacRae’s interest in and skill with poetic form, we need look no further than the extraordinary glose on a quatrain from Alice Oswald (the earlier collection contained another on lines from Mary Oliver). For most poets, this form is little more than an exhibitionist high-wire act, but MacRae’s poems are moving and complete. Her use of poetic form here, particularly in some of these last poems, reminds me of Tony Harrison’s conviction that its containment “is like a life-support system. It means I feel I can go closer to the fire, deeper into the darkness . . . I know I have this rhythm to carry me to the other side” (Tony Harrison: Critical Anthology, ed. Astley, Bloodaxe Books, 1991, p.43). Appropriately, in ‘Jar’, she contemplates with admiration an object that has “gone through fire, / risen from ashes and bone-shards / to float, nameless, into our air”. Here, the narrator movingly lays aside the wary scepticism of the Thomas epigraph and rests her cheek on the jar’s warmth to “feel its gravity-pull / as if it proved the afterlife of things”.