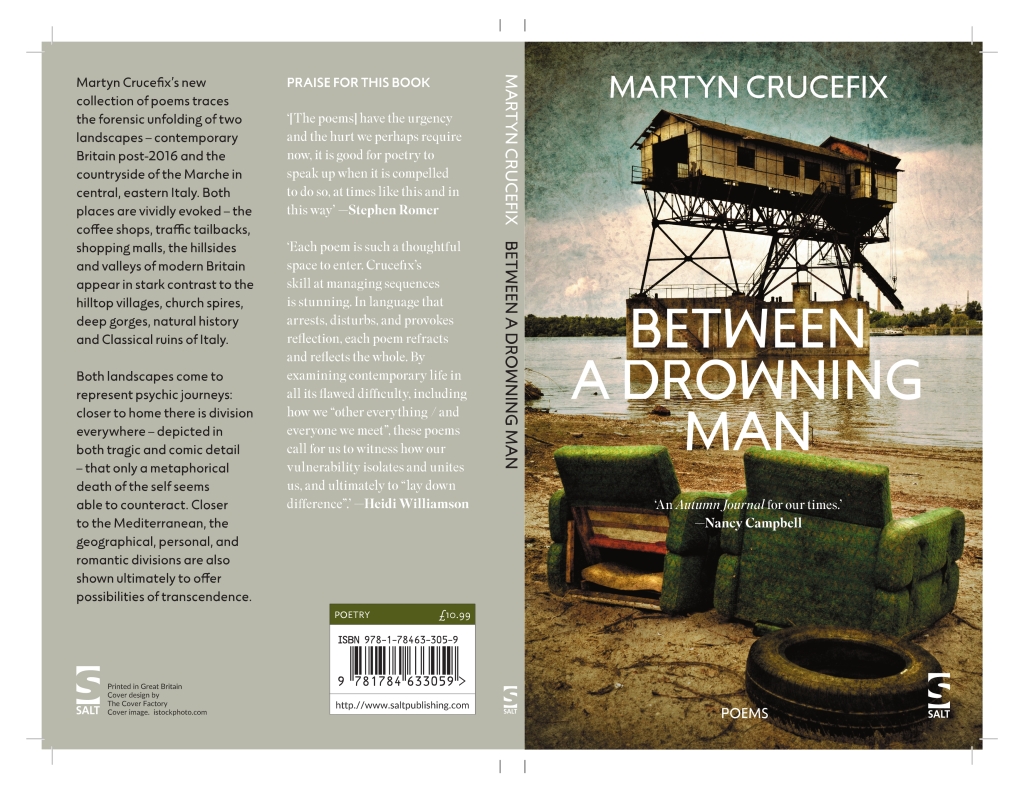

Many thanks to Mat Riches for this fulsome and acute reading of my recent collection from Salt Publishing. The review first appeared on The High Window – Jan 2024

The introduction to the first section of Between a Drowning Man states that it draws on two texts. The first is Hesiod’s Works and Days, and the second of which is described as

the type of poem known as a vacanna originated in the bhakti religious protest movements in 10-12th century India. using plain language, repetition and refrain they were written to praise the god, Siva, though also expressed a great deal of personal anger, puzzlement, even despair about the human condition […]

This helped put everything into context for what followed. One third of the way in I started to think of it as a man shouting at clouds in book form, of someone railing at things in the world that are beyond our control. And maybe it is all of this, but it also much more than this. I think it becomes a lesson in acceptance.

In a post on his own Blog, Crucefix describes these poems as starting to arrive after reading the vacanna poems in 2016, and how the poems began to accumulate after that while ‘staying in Keswick at the time and I vividly remember scribbling down brief pieces at all times of the day and night’ and of having been influenced by Brexit (the bridges are down indeed). However, he also describes in a follow up post that:

I thought of the poetry I was writing as a quite narrowly focused topical intervention, but in the last 4 or 5 years …the poems have come to seem less dependent on their times and more capable of being read as a series of observations – and passionate pleas – for a more generous, open-minded, less extremist, less egotistical UK culture.

And while the Brexit reading is there, these poems speak more to grounding a modern and disconnected world (despite plenty of references to devices for and modes of communication—we’ll come back to that shortly) in timeless themes like love and desire, parenting, ageing, joy in nature, false idols, and much more, and this is just in the first twenty or so pages.

Picking one of those themes at random, we can see how false idols are covered, but also how deftly he weaves in modern references to something that is both timeless, and of its time, and with that very human. In ‘the six pack on the side’ we are told:

the clock is a sinister and impassive god

for the ancients rumour was a kind of god

…

the god of WiFi when we curse its absence

and when did difference become a god

We have always been a narcissistic species that pays attention to gossip (‘rumour was a kind of god’), but while our gods have changed as the centuries have passed, we still curse our gods when they forsake us. Not a bad return for a 19-line poem in my opinion.

In order to achieve the ‘more generous, open-minded, less extremist, less egotistical UK culture’ we can see several pleas for more open lines of communication throughout the poems. Some are located in the specific and familial, as in ‘watch the child’ and its discussion of a child chattering away to herself in a coffee shop with her ‘bright picture book’ juxtaposed with ‘her mother at her cooling latte / at her macchiato / at her cooling skinny medium cappuccino // […] her mother’s ears wired casually // with two scarlet buds.

The child is broadcasting and communicating in a carefree way vs the mother’s more deliberate inward-looking approach, a shutting the world out for some respite. And while this could be a judgmental poem; it’s not. It feels like an invitation to consider both sides, both needs here. The refrain of ‘all the bridges are down’ lands particularly well here, both for the protagonists of the poem, but also for the reader.

However, while some pleas are located in the specific there are some more general ones to be found. In ‘he thought of this time’ one man recounts a litany of disappointments and emotions from his father. The poem draws from Hesiod and his idea of the fifth age where modern man was created by Zeus to be evil, selfish, weary, and burdened with sorrow. It’s a two-footed tackle on humanity from the whistle:

he thought of this time as a fifth age

that he’d be better off dead or not yet born

working all day he would fear the night

had heard of children born prematurely grey

and the fraying bond between fathers

and sons between mothers and daughters

between host and guest between different races

It continues without reprieve about a world where:

[…]the hopeless

are advanced and further advancement

lavished for no more than just chancing it

respect a word more spoken than heard

the educated full of corrosive cleverness

and compassion the greatest of virtues

an ebbing tide you see where it glints

on the horizon

At the time of writing, it’s easy to feel like these lines are as contemporary as it’s possible to be, and yet it’s arguable they are evergreen observations about humanity. However, I suspect that’s the point.

We’ve touched upon references to modern-day totems like WiFi, coffee types and headphones already, but this section is filled with them. Further examples include references to Google Maps and ‘five-star online reviews’ in ‘fifteen kilometres of traffic’ and ‘stoke a fire under your silk blouse’ respectively.

This all reaches its zenith in the final poem of the section, ‘this morning round noon’. The poem moves from personal notes about scattering ashes, a son’s birthday (and him being in huge debt at 21, one presumes from being at university) through to:

an American punk band form Nashville

posting abuse about a young Buddhist woman

refusing anaesthetic

The lines are punctuated by phrases like ‘likesharelike’ or ‘likeclicklike’ or ‘smileyfaceicon’. It’s the diaristic nature of the whole section writ large and transmitting thoughts to the page (albeit the printed page, not the Facebook page) as they occur. As an aside, this running together of words, coupled with the entire book’s distinct and clearly deliberate lack of punctuation (save a few dashes here and there) add to the observational nature of the poems, of thoughts being pulled from the ether. However, this is very much not to say that these poems aren’t considered and crafted—they very much are.

The final line of the poem and section is ‘I say the Pantone chart is one of my favourite things’, and while the poem that proceeds this line could be read as a darker version of the Sound of Music classic, less Raindrops on roses and more ‘I was hit by a car likeshare’, but I prefer to take it as a sign that the poem end on acceptance of nuance, variation and being able to communicate the same needs.

As the first section comes to an end there are two poems where the last line of one resurfaces as the start of the next, and it feels like a teaser for what follows in the second section, O. at the Edge of the Gorge.

This was previously published as a pamphlet by Guillemot Press in 2017 and is a crown of sonnets. After the hectic modernity of the first section, there is much to be said for the relative calm of following a traveller, Orpheus, on a journey through Italian countryside observing ‘Glossy fleet black clods of carpenter bees / swirl at the corner of the house / then sink onto spindly lavender stems / alight on blooms stooped // with the weight of insect lives’.

It’s a beautiful opening and a beautiful image that should perhaps be filmed and used as a fine example of what was briefly known as slow TV and shown on BBC4, but in the second poem he describes ‘astronomical time marked by light’ as the sun descends the gorge and church bells tolling, but:

yet come nightfall a different sense

these same sounds sound notes more chilling…

A very real sense of for whom the bell tolls, indeed. As the traveller wends their way round the area, taking notes and sketches of birds, a ‘flock of white doves’, that darkness returns in the form of a buzzard in the eighth sonnet, and gets deeper still in the ninth where he mentions:

like Urbisaglia or some place has seen

and survived change of use

from sacred temple to church to slaughterhouse

and no gully nor hill can stop it

Urbisaglia is an ancient town in Mid-East Italy that became the site of an internment camp during the second world war, and that knowledge adds further weight to the stanza that begins sonnet ten:

The truth is some survive a while most fail

to conceive the scale of paperwork

to follow change of use from church to temple

next to slaughterhouse.

The cruelty of humanity to itself is mirrored in the “bloody festival / of the bird” in sonnet thirteen as it discusses a raptor above the gorge, and the final sonnet off this crown muses on the fragility of life:

All creatures die sooner blind to the hawk—

left clutching no more than this

as if the hammock he occupies each

and all night too as if strung out

[…]

not falling yet not ever at ease

‘not ever at ease’ could so easily be a final motif for the whole collection. There is a sense that the learnings of this collection are hard won, but there is a connection to the wider world to be had, and that we can find comfort in travelling through it. The final lines of ‘you are not in search of’ in the first section seem apt as a place to leave it:

you might say this aloud—by way of ritual—

there goes one who thought much of life

who found joy in return for a little gratitude.

Mat Riches is ITV’s unofficial poet-in-residence. Recent work has been in Wild Court, The New Statesman, The Friday Poem, Bad Lilies, Frogmore Papers and Finished Creatures. He co-runs Rogue Strands poetry evenings. A pamphlet called Collecting the Data is out via Red Squirrel Press. Twitter @matriches Blog: Wear The Fox Hat

Chen Xianfa is a prize-winning poet and journalist, born in Anhui Province, China. He has published five books of poems: Death in the Spring (1994), Past Life (2005), Engraving the Tombstone (2011), On Raising Cranes (2015; in English tr. 2017) and Poems in Nines (2018; bilingual Chinese/English, tr. Nancy Feng Liang, publ. China) which was awarded the Lu Xun Prize. A Selected Poems appeared in 2019. He has published two collections of essays, Heichiba Notes (2014 and 2021). Other awards include China’s Top Ten Influential Poets (1998-2008), the Hainan Biennial Poetry Prize (2011), Yuan Kejia Poetry Prize (2013), Tian Wen Poetry Prize (2015) and the Chenzi’ang Poetry Prize (2016).

Chen Xianfa is a prize-winning poet and journalist, born in Anhui Province, China. He has published five books of poems: Death in the Spring (1994), Past Life (2005), Engraving the Tombstone (2011), On Raising Cranes (2015; in English tr. 2017) and Poems in Nines (2018; bilingual Chinese/English, tr. Nancy Feng Liang, publ. China) which was awarded the Lu Xun Prize. A Selected Poems appeared in 2019. He has published two collections of essays, Heichiba Notes (2014 and 2021). Other awards include China’s Top Ten Influential Poets (1998-2008), the Hainan Biennial Poetry Prize (2011), Yuan Kejia Poetry Prize (2013), Tian Wen Poetry Prize (2015) and the Chenzi’ang Poetry Prize (2016).