One of my very first reviews here – in August 2014 – was of Liz Berry’s Black Country. I was so impressed with the ways in which she exerted “pressure to counter the hegemonies of language, gender, locality, even of perception”. Most obviously she was doing this through the use of her own Black Country dialect, but I thought a more profound aspect of this was how “so many poems unfold[ed] as processes of self-transformation”; transgressive energies were being released through language, the erotic, myth-making and the surreal. The earlier book concluded with poems anticipating the birth of a child and – at the time – I felt these were less startlingly good, inclined to fall into ways of saying that the rest of the collection so triumphantly avoided.

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood (Chatto, 2018) – to read more of Berry’s poems written since then, since the birth of her two sons and after a period of relative creative silence (more of that later). I nominated six stand-out poems from Black Country that I felt would establish her reputation – and the title poem of this pamphlet must be added to that list. It’s the most political of the fifteen poems and is propelled by the tensions located between motherhood as social norm or expectation and the personal/social grain of that particular experience. The paradox of the opening lines is that entering into the republic of motherhood (shades of Seamus Heaney’s 1987 The Haw Lantern, with its ‘From the Republic of Conscience’), the mother also discovers a monarchy, a “queendom, a wild queendom”. Much of the poem lists the realities of early motherhood – the night feeds, the smelly clothes, the exhaustion, the clinics and queues – a great democracy of women taking up a particular role. But there are signs too of an external compulsion, a set of expectations to be lived up to. The mother is expected to play the queen too as she pushes her pram down “the wide boulevards of Motherhood / where poplars ben[d] their branches to stroke my brow”. The public role of motherhood comes with demands: “As required, I stood beneath the flag of Motherhood / and opened my mouth although I did not know the anthem”. As much as any new parent feels woefully inadequate and ignorant of the needs of their young child, the young mother is faced with additional social expectations about instinct, affection, abilities and fulfilment which are quite impossible to realise. And on this point, there remains a conspiracy of silence: “[I] wrote letters of complaint / to the department of Motherhood but received no response”.

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood (Chatto, 2018) – to read more of Berry’s poems written since then, since the birth of her two sons and after a period of relative creative silence (more of that later). I nominated six stand-out poems from Black Country that I felt would establish her reputation – and the title poem of this pamphlet must be added to that list. It’s the most political of the fifteen poems and is propelled by the tensions located between motherhood as social norm or expectation and the personal/social grain of that particular experience. The paradox of the opening lines is that entering into the republic of motherhood (shades of Seamus Heaney’s 1987 The Haw Lantern, with its ‘From the Republic of Conscience’), the mother also discovers a monarchy, a “queendom, a wild queendom”. Much of the poem lists the realities of early motherhood – the night feeds, the smelly clothes, the exhaustion, the clinics and queues – a great democracy of women taking up a particular role. But there are signs too of an external compulsion, a set of expectations to be lived up to. The mother is expected to play the queen too as she pushes her pram down “the wide boulevards of Motherhood / where poplars ben[d] their branches to stroke my brow”. The public role of motherhood comes with demands: “As required, I stood beneath the flag of Motherhood / and opened my mouth although I did not know the anthem”. As much as any new parent feels woefully inadequate and ignorant of the needs of their young child, the young mother is faced with additional social expectations about instinct, affection, abilities and fulfilment which are quite impossible to realise. And on this point, there remains a conspiracy of silence: “[I] wrote letters of complaint / to the department of Motherhood but received no response”.

The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”. Listen to Liz Berry talk about and read this poem here.

The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”. Listen to Liz Berry talk about and read this poem here.

After the tour de force of ‘The Republic of Motherhood’, the pamphlet takes a more chronological track. ‘Connemara’ seems to mark the moment of conception as a moment of self-abandonment (“I threw the skin to the wind, / sweet sack”) which, in the light of the preceding poem, takes on greater ironies of naivety: “Let them come, / I thought, / I am ready.” One of the joys of Berry’s work is her sense of the animal-physicality of the human body (revel in ‘Sow’ from Black Country) and ‘Horse Heart’ figures a ward of expectant mothers as a farmyard stable: “the sodden hay of broken waters, / each of us private and lowing in our stalls”. She captures the high anticipation and potentially brutal arrival of the all-demanding babies as a herd of horses; “the endless running / of the herd, fear of hoof / upon my chest”. These two poems can be read here.

Birth itself, in ‘Transition’, is to be feared (“I wanted to crawl into that lake at Kejimakujik”) and gotten through in part by absenting oneself into the past in ‘The Visitation’. The latter is addressed to Eloise, a figure who appeared in a Black Country poem, ‘Christmas Eve’. Here, a schoolgirl memory of a loving encounter with Eloise takes the narrator away from the pains of contractions, “as my body clenched and unfurled”. ‘Sky Birth’ is the one poem that challenges the brilliance of ‘The Republic of Motherhood’. It takes the image of climbing a mountain to evoke the physical pain and endurance required (Berry welcomes all those traditional associations with spiritual climb and progress), yet the poem never loses its sense of the real situation. The breathlessness of the climb suddenly flips back to the mother howling “over the voice of the midwife, the beeping monitors”. It is the figurative climb as much as the literal pain of giving birth that makes her “retch with the heights” and in the final moments, the mountaineer is “knelt on all fours” as most likely was the mother-to-be. The height is reached in a moving conceit:

when it came it came fast, a shining crown

through the slap of the storm,

for a second we were alone on that highest place

and love, oh love,

I would have gladly left my body

on that lit ledge for birds to pick clean

for my heart was in yours now

and your small body would be the one to carry us.

That final plural personal pronoun reminds me of a comment made by Jonathan Edwards in reviewing this pamphlet. Edwards wonders briefly about the absence of the father figure. Is the ‘us’ here the mother and child? Or is this one of the few references in the pamphlet to both parents?

I hope this is not just a male reviewer’s concern. It may be an artistic or political decision on Berry’s part. Or a personal one. But given the thrust of much of the work – that mothering is an utterly taxing and even deranging experience – I’m troubled by the father figure’s absence, if only in that it risks representing the idea (the toxic flip-side to the expectations laid on the mother) that fathers need have little part to play. The father does appear in the final poem, ‘The Steps’, though the questioning tone and syntax casts doubt over what of the parents’ relationship will survive the experience of the child’s arrival: “Will we still touch each other’s faces / in the darkness”. I also wonder if the father figure is implied in the image of a boy riding his bike up Beacon Hill in ‘Bobowler’. This is a beautiful poem on the image of a moth (‘bobowler’ is the Black Country word for a moth). The moth is a messenger, coming to all “night birds”. The boy on the bike is one such, his heart “thundering / like a strange summer storm” which perhaps echoes those thundering hooves of the approaching young child. Perhaps there is some recognition here that the father’s world too will be turned upside down. And the message the bobowler brings may also relate to the parental relationship: “I am waiting. / The love that lit the darkness between us / has not been lost”.

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

‘So Tenderly It Wounds Them’ is a more public account of the trials of young motherhood, of women who “are lonely/ though never alone”, women who find themselves “changed / beyond all knowing”, waking each morning only to feel “punched out by love”. The more recent poem ‘The Suburbs’ also contains the same paradox that motherhood is a state of “tenderness and fury”. ‘Marie’ seems to record a debt to a supportive female friend and it is only through the ministering (that seems the apt word) of “women in darkness, / women with babies” in ‘The Spiritualist Church’ that the young mother’s despair has any hope of being redeemed. Redeemed, not solved, of course: what the women argue is that “love can take this shape” and perhaps it Berry’s sense of art, or her personal experience, or a recognition of human resilience, or a final succumbing to a traditional narrative, that makes her place ‘Lullaby’ as the penultimate poem. It ends sweetly though the final poem sends us back to the start of it all – the dash to the hospital. So Berry book-ends this little gem of a collection with time shifts that argue motherhood’s simultaneous complexity of animal and human love as well as its pain and awful boredom and personal diminishment.

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

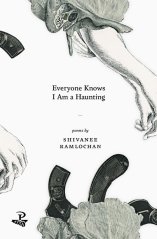

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

You will have gathered that one of Power’s things is to mix English and Austrian German. This happens several times in ‘A Tour of Shrines of Upper Austria’ (though in this book we only get 7 parts of the full sequence). An observer stops at various shrine sites, jotting down some thoughts and taking a picture or two. Nothing is developed though Power’s poems do show an interest in religion on several other occasions. ‘The Moving Swan’ opens with a centre-justified prose description of candles flickering in a cathedral and another poem is drawn to the grave of two goats, observing: “two heaps of ivy/straw / one unlit red tealight”. And ‘Epiphany Night’ is a more extended series of notes recording a local celebration with bells, dressing-up, boats, lanterns. This is all observed in loosely irregular lines by the narrator from her “wohnung” (apartment). To wring all engagement or emotional or imaginative response from such a text is, I suppose, quite an achievement but to spend 70-odd pages in such company really is wearisome.

You will have gathered that one of Power’s things is to mix English and Austrian German. This happens several times in ‘A Tour of Shrines of Upper Austria’ (though in this book we only get 7 parts of the full sequence). An observer stops at various shrine sites, jotting down some thoughts and taking a picture or two. Nothing is developed though Power’s poems do show an interest in religion on several other occasions. ‘The Moving Swan’ opens with a centre-justified prose description of candles flickering in a cathedral and another poem is drawn to the grave of two goats, observing: “two heaps of ivy/straw / one unlit red tealight”. And ‘Epiphany Night’ is a more extended series of notes recording a local celebration with bells, dressing-up, boats, lanterns. This is all observed in loosely irregular lines by the narrator from her “wohnung” (apartment). To wring all engagement or emotional or imaginative response from such a text is, I suppose, quite an achievement but to spend 70-odd pages in such company really is wearisome.

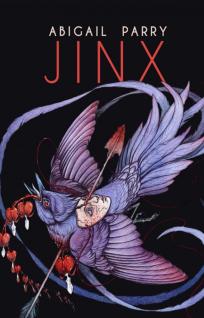

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”.

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”. For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?

For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?

![p045rwch[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/p045rwch1.jpg?w=354&h=199)

![train[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/train1.jpg?w=700)

![DuncanForbes-200x245[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/duncanforbes-200x2451.jpg?w=700)

![blogcharlescausley2[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/blogcharlescausley21.jpg?w=325&h=219)

![wp2f72b580_06[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/wp2f72b580_061.png?w=700)