I have not blogged regularly since April 2017 as, having managed to get both my parents settled into a Care Home in Wiltshire, Dad suffered a series of heart attacks and died – fairly quickly and peacefully – on May 24th. Not wholly coincidentally, the Spring 2017 issue of Poetry London published an essay I had written which starts and ends with some thoughts on my experiences with my father and his growing dementia. In the next two blogs, I re-produce this essay unchanged in the hope that it still says something of value about types of ‘confusion’ and in memory of a man who would have had little time for such (in his view morbid and abstruse) reflections. Thanks to Tim Dooley who commissioned the essay for Poetry London and published it under the original title: A Straining Eye Catches no Glimpse.

Part 1

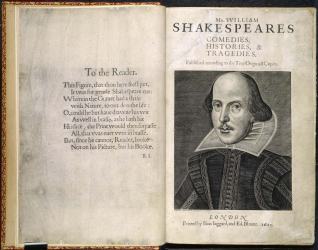

An old king leans over his daughter’s body seeking signs of life, yet he finds “Nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing”. Given that I teach literature and this is one of Shakespeare’s more famous lines with its repetition and trochaic revision of the iambic pentameter, I’m not proud of mis-remembering this moment in King Lear (the repeated word is, of course, ‘Never’). Yet I know why I mistake it, this year, in these fretful months. Seeing Anthony Sher play the role recently – haranguing a foot-stool, giving toasted cheese to a non-existent mouse – put me in mind of my father, though he’s not quite so far gone. These days he has trouble recognising the house he’s lived in for 60 years; he will refer to his wife as a woman from the village who has come to look after him; he seeks news of his mother (she died in the 1970s). What can this feel like? Years of memories gone; a whirling fantasmagoria that evidently frightens him; a something becoming nothing he makes too little sense of.

So it’s not just that the idea of nothing is prominent from the very start of Shakespeare’s play. Cordelia fails to reply flatteringly to Lear’s question about which of his daughters loves him most. The gist of her brutal answer is “Nothing, my lord”. Lear warns her: “Nothing will come of nothing. Speak again”. But she sticks to what she sees as her truth (as against her elder sisters’ oleaginous falsehoods) and pays the consequences. But so does the King. Reduced eventually to a wholly unexpected state of wretched nothingness in the storm scenes and beyond, he learns much from this nothing in pointed contradiction of his earlier warning. It doesn’t stop there; once reunited with Cordelia and faced with the prospect of prison, possible execution, what is remarkable is the King’s acceptance of his fate. Confronting this further reductio, he declares he’ll go and finds a reason to be cheerful: “we will take upon’s the mystery of things”. I’ve always been struck by Shakespeare’s phrasing here. The mystery of things is imaged not as some modernly pedagogic check-list, tabulated and absorbed like a set of principles, rather it’s something to be folded about us – a garment, an investiture, a way of seeing, feeling, not quite of self, not quite other either – and Shakespeare’s point is that Lear’s encounter with nothingness in various guises is what has prepared him for such a re-vision of his place in the world.

I’m interested in the idea that such a nothing can be worth something. Of course, it’s not exactly nothing, a void, that Cordelia’s father encounters. It is a bewildering set of experiences of which he can make nothing. Lear – I don’t know how far this is like my father – suffers because his previous paradigms are failing: he is shocked into his encounter with the mystery of things or what Anne Carson calls the “dementia of the real”. When my father talks, he yearns for the ordinary reassuring certainties of his old life, as if they would close round him with the feel of a comfortable coat. Carson has explored this reliance we all have on the familiar in her 2013 Poetry Society lecture concerned with ‘Stammering, Stops, Silence: on the Methods and Uses of Untranslation’.[i] She explores moments when language ceases to perform what we consider its primary function and we are confronted with nothingness in the form of silence. In the fifth book of The Odyssey when Hermes gives Odysseus the herb “MVLU”, Homer intends the name of the plant to be untranslatable since this sort of arcane knowledge belongs only to the gods. In a second example, under interrogation at her trial, Joan of Arc refuses to employ any of the conventional tropes, images or narratives to explain the source of her inspiration. Carson wants to praise Joan’s genius as a “rage against cliché”, the latter defined as our resort to something pre-resolved, pre-shaped, because, in the face of something so unfamiliar that it may seem more like nothing, “it’s easier than trying to make up something new”.

Carson associates this rage to ‘out’ the real with Lily Briscoe’s problems as an artist in Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. She struggles to complete her painting, aware that the issue is to “get hold of something that evaded her”.[ii] She dimly senses “Phrases came. Visions came. Beautiful pictures. Beautiful phrases. But what she wished to get hold of was that very jar on the nerves, the thing itself before it had been made anything”. Unlike Homer and Joan of Arc, the knowledge Lily seeks (undistracted by the divine) is not so much prohibited as, in a profound sense, beyond conception (it is a nothing before it has been made something). For Carson, we each dwell behind the “screens” of cliché for most of our lives, so when the artist pulls them aside the impact of the revelation may well have the force of violence. She suggests artistic freedom and practice lie in such a “gesture of rage”, the smashing of the pre-conceived to find the truth beyond it, her goal remaining the articulation of the nothing she insists is actually the “wide-open pointless meaningless directionless dementia of the real”.

This is the nothing I am interested in: it is no void or vacancy but, paradoxically, a wealth of experience, a “flux of phenomena” about which we cannot think in conventional ways. We cannot name the parts of it, so for convenience, maybe a bit defensively, we prefer to designate it nothing. The artist seeks to articulate such an “experience of what goes beyond words: call it the fleeting perception [. . . ] a state of indifferentiation”. [iii] This is one of the many formulations of the issue by the late Yves Bonnefoy who unrelentingly explored the limits of conceptual thinking in terms similar to Carson’s distrust of cliché: “It is not that I incriminate the concept – which is merely a tool we use to give form to a place where we can dwell. I am merely pointing out a bad tendency [ . . . ] of its discourse to close discussion down, to reduce to the schematic and to produce an ideology existing in negation of our full relation to what is and to whom we are”. He concludes it is a “temptation to stifle dissenting voices” – the kind of voices who see something in nothing. [iv]

The always evangelical Bonnefoy terms the mystery encountered in a “state of indifferentiation” as “Presence”. In 1991, Bonnefoy’s temporary residence in the snowy landscapes of Massachusetts gave him a new way of evoking these ideas. In The Beginning and the End of the Snow (1991) he reads a book only to find “Page after page, / Nothing but indecipherable signs, / [. . .] And beneath them the white of an abyss”[v]. Later, the abyss is more explicitly, if paradoxically, identified: “May the great snow be the whole, the nothingness”.[vi] These occasional moments when the screens of cliche and conceptual thought fall are moments of vision as sketched by Auden in his discussion of Shakespeare’s sonnets – they are given, not willed; are persuasively real, yet numinous; they demand a self-extinguishing attentiveness.[vii] The inadequate, provisional, always suspect nature of language to record such moments is clear in these lines from Bonnefoy’s poem ‘The Torches’:

. . . in spite of so much fever in speech,

And so much nostalgia in memory,

May our words no longer seek other words, but neighbour them,

Draw beside them, simply,

And if one has brushed another, if they unite,

This will still be only your light,

Our brevity scattering,

Our writing dissipating, its task finished.[viii]

Rather than the forced disjunctions and the quasi-dementia of Carson’s recommended methods, Bonnefoy is reluctant to abandon the lyric voice, though he still intends to acknowledge the provisional nature of language in relation to Presence. The “fever” and “nostalgia” we suffer is the retrogressive lure of conceptual simplification. Bonnefoy’s imagery suggests a more delicate, tentative relationship between words, a neighbouring, a brushing up against each other (like snowflakes), though even then, if they “unite” or manage to cast “light” on what is, this can only be brief, always subject to dissipation.

(to be continued)

Footnotes

[i] Poetry Review, Vol. 103, No. 4 (Winter 2013).

[ii] Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse (1927; Penguin Modern Classics, 1992), p. 209.

[iii] Yves Bonnefoy, In the Shadow’s Light, tr. Naughton (Chicago Press, 1991), interview with John Naughton, p. 162.

[iv] Yves Bonnefoy, ‘The Place of Grasses’ (2008), in The Arriere-pays, tr. Stephen Romer (Seagull Books, 2012), pp. 176/7.

[v] Yves Bonnefoy, ‘Hopkins Forest’, tr. Naughton in Yves Bonnefoy: New and Selected Poems, eds. Naughton and Rudolf (Carcanet, 1996), p. 181.

[vi] Yves Bonnefoy, ‘The Whole, the Nothingness’, tr. Naughton, Naughton and Rudolf, p. 187.

[vii] W. H. Auden, ‘Introduction to Shakespeare’s Sonnets’ (1964; reprinted in William Shakespeare: The Sonnets and Narrative Poems, ed. William Burto (Everyman, 1992)).

[viii] tr. Naughton, Naughton and Rudolf, p. 177.