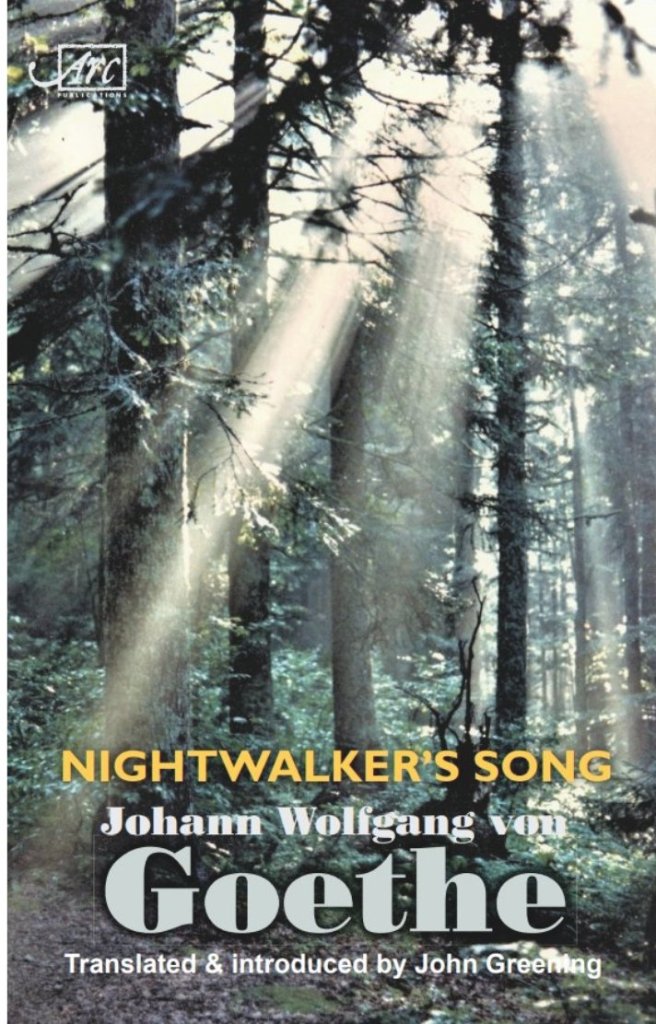

In this blog post, I am discussing John Greening’s new translations of a small selection (9 poems in all) from the works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. With the original German texts provided on facing pages, these translations are published as Nightwalker’s Song, by Arc Publications (2022). This review was originally commisioned and published by Acumen poetry magazine early in 2023. By the way, Acumen will be presenting a free to attend on-line celebration of its latest issue on Friday September 1st at 18.30 BST. It will include a brief reading of new work by yours truly, Gill McEvoy, Anthony Lawrence , Sarah Wimbush, Simon Richey, Dinah Livingstone, Michael Wilkinson, Jill Boucher, Jeremy Page, and others.

John Greening’s recent, self-confessedly ‘tightly-focused’ little selection from Goethe’s vast output is, in part, a campaigning publication. In his Introduction, Greening notes the difficulties surrounding the great German poet’s presence in English: the sheer volume of work, the range of that work, the man’s polymathic achievements (as poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, critic), the long life untidily straddling all neat, period pigeon-holing. Christopher Reid has called him ‘the most forbidding of the great European poets’, but perhaps the English have come to see him as a mere jack-of-all-trades? And where do we turn to read and enjoy the poetry? Michael Hamburger’s and Christopher Middleton’s translations look more and more dated. David Luke’s Penguin Selected (1964; versified in 2005)is the most reliable source. But tellingly, as Greening says, one does not find young, contemporary poets offering individual translations of Goethe in their latest slim volume in the way we do with poems by Rilke or Hölderlin.

So here Greening sets out a selection box of various Goethes to encourage other translators: we find nature poetry, romance, the artist as rebel, meditations on fate, erotic love poems, a rollicking ballad, dramatic monologue and a very fine sonnet. I like Greening’s determination not to lose the singing. Here, he has ‘shadowed’ the original metres and retained rhyme schemes, though he sensibly makes more use of pararhyme than Goethe’s full rhyming. While not approaching Lowellesque ‘imitations’, Greening has also sought a ‘contemporary texture’ by venturing to ‘modernise an image or an idea if it helped the poem adapt to a different age’. For example, in ‘Harz Mountains, Winter Journey’ (‘Harzreise im Winter’) Goethe’s buzzard has become the more familiar image, in southern England at least, of a red kite. The carriage or wagon (‘Wagen’) driven by Fortune becomes a car in a ‘motorcade’ and another vehicle is imagined ‘winking on to / the slip-road’. There’s also an enjoyable touch of Auden in Greening’s updating of ‘crumbling cliffs / and disused airfields’ (Middleton has ‘On impassable tracks / Through the void countryside’).

Greening’s skills in versification are well known and he deploys them all – and you can hear him enjoying himself – in ‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’: ‘Broomstick – up, it’s show time, haul your / glad rags on, so grey and grimy. / Seems you’ve seen long service, all you’re / fit for now is to obey me’. Though grace notes and fillers slow Goethe’s headlong verse (the opening line in German is simply ‘Und nun komm, du alter Besen!’ – ‘And now come on, you old broom!’), Greening’s rhyming is delightful and the modernising phrases (show time, glad rags) drive the poem along with a colloquial energy which is absolutely right.

Goethe’s ‘Prometheus’ – published in 1789, the year of revolution in France – is a growling dramatic monologue in which the rebel Titan (who stole fire from the gods to give to humankind) sneers and mocks the authority figure, Zeus. He belittles the top god in the opening lines by comparing him to a boy, thoughtlessly knocking the heads off thistles. Greening catches the mocking tone in the series of rhetorical questions later in the poem: ‘Honour you? For what? / Have you ever offered to lift / this agony?’ Prometheus ends – following one version of his story – by explaining he is creating the human race in his own image, ‘a new range’ translates Greening, neatly updating once more, ‘programmed / to suffer and to weep, or whoop and punch the air – / but who, like me, won’t care / about you’. In comparison, Luke’s version sounds rather fusty and less bolshie: ‘A race that shall suffer and weep / And know joy and delight too, / And heed you no more / Than I do!’

Goethe is a great love poet. ‘Welcome and Farewell’ (‘Willkommen und Abschied‘) has a man approaching on horseback (Greening does not motorise on this occasion) through a moonlit landscape and the lover is spied at last: ‘how / I’d dreamt of (not deserved) all this’. The moment of union passes unspoken between stanzas three and four. As if instantaneously, now ‘the sun had risen’ and the parting must take place: ‘And yet, to have been loved – to love, / ye gods, such utter happiness’. It’s curious that Greening retains the rather archaic ‘ye gods’. One still hears the phrase, of course, but with more irony than I would have imagined here. The fifth of Goethe’s ‘Roman Elegies’ is a fabulous erotic piece. Written during the poet’s travels to Italy in the late 1780s, the narrator is studying classical culture by day and his female lover’s body by night. The latter nourishes the former: ‘I find I appreciate marble all the better for it, / and see with a feeling eye, feel with a seeing hand’. As he goes on, ‘compare and contrast’, I find Greening a little cool here. There is a selection of translations by D M Black (Love as Landscape Painter, from FRAS Publications in 2006) which generates more heat:

Yet how is it not learning, to scan that delectable bosom,

Or when I slither my hands pleasantly over her hips?

Then I understand marble; then I discover connections,

See with a feeling eye, feel with a seeing hand.

Goethe’s Faust is represented here by the scholar’s opening speech to Part One (versioned, as it were, by Christopher Marlowe in the opening soliloquy of his Doctor Faustus). Greening excels in the handling of rhyme and line length, even compared to David Constantine’s 2005 Penguin translation. Perhaps most impressive of all is the sonnet ‘Nature and Art’ (‘Natur und Kunst’). Greening has the motor car in mind again in his updating of Goethe’s exploration of how the artist must labour incessantly to achieve the preparedness, the readiness to respond to Nature, to what is natural. Reading these lines, you feel Greening is translating as a skilled and experienced artist himself, triumphantly bringing a poem written in 1800 bang up to date:

It’s just a case of working long and late.

So once we’ve spent, let’s say, ten thousand hours

on steering, footwork, shifting through the gears,

it may be then some natural move feels right.

x

Creative though you be, you’ll strive in vain

to reach perfection if you’ve no technique,

however wired and woke your gifts may be.

x

You want a masterpiece? You’ll need to strain

those sinews, set your limits, drill and hack.

The rules are all we have to set us free.

For anyone yet to make the leap into Goethe-world, this little book is a terrific way into the great German writer’s work and such a reader will find Greening’s Introduction and his prefatory remarks to each of the chosen poems very helpful indeed. I recommend this collection.