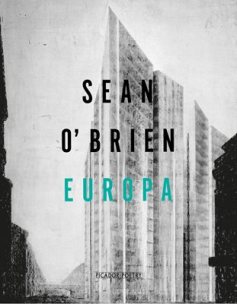

Sean O’Brien’s recent book, Europa (Picador Poetry, 2018) has made it onto the 2018 T.S. Eliot award shortlist. Earlier in the year, I was asked by Magma magazine on-line to write a brief review of the book (alongside Vahni Capildeo’s Venus as a Bear (Carcanet Press, 2018) and Alice Miller’s Nowhere Nearer (Liverpool University Press, 2018). What follows is an expanded version of my original review of O’Brien’s book.

You know why they chose to do it but Picador’s presentation of Sean O’Brien’s ninth collection as a book about Brexit does nobody any favours. It’s a far more heterogeneous set of poems – there’s a good dose of elegiac texts, for example – though the opening 19 pages certainly does have the UK and Europe steadily in their sights. It turns out, what these two blocs share in O’Brien’s view, is a history which is ironically mostly one of conflict (a view also reflected in O’Brien’s Robert Graves Society lecture recently published in P.N. Review 244) . The opening poem, ‘You Are Now Entering Europa’ repeats the line, “The grass moves on the mass graves”. The poem goes on to ask how many “divisions” the grass has at this activity and the play on words manages to evoke both military logistics as well as peace-time political conflicts. The narrative voice is downcast, speaking in short breathless little phrases as if anything more lengthy would be beyond him or not worth it. The steadying recourse is merely “my work” which serves to sustain but for no other obvious purpose than to arrive at “the graveyard I become”.

Other poems draw on material from the Great War or the Balkan conflict while ‘Wrong Number’ looks back to visits to the divided city of Berlin, visits that read like a catalogue of failures ending in a self-regarding and (later) self-ironised “species of moral exhaustion”. How effectively poetry – or a literary sensibility – can engage with what is really existing in political terms is one of the themes here:

I chose not to mention this

Because it was too obvious or literary,

Like making something out of nothing

For the sake of poetry, as if that were a sin.

But O’Brien is always at his best engaging in his love/hate relationship with England. ‘Dead Ground’ explores who owns the English countryside. It describes a ‘theme park’ landscape, a fantasy “[w]here things are otherwise” than what they really are, yet an exclusive park round which ancient walls “will be built again, but taller”. O’Brien’s second person addresses are always discomfiting, levelling an accusing finger at the reader more than most contemporary poets though it’s effect is complicated by the clear sense that he implicates himself as well. Art again gets short shrift – here it is batted away as “[t]he never-was and never-will” in contrast to the brute facts of ownership and possession. Is it the sensibility of the artist/poet again being prodded and provoked here: “The liberties you think you claim / By searching out the detail / In the detail”? Again, this is a task that seems to end nowhere better than “your six-foot plot”. In fact, in O’Brien’s vision of contemporary England, the most vital activity is wholly mercenary, “counting the takings”.

Those who live outside this country’s circles of possession and privilege, those to be found in “Albion’s excluded middle”, are more than likely to end up in the kind of neo-Nazi meeting so brilliantly described in ‘The Chase’. Here, in Function Rooms where “gravy fights it out with Harpic” O’Brien finds “[w]ould be Werwolfs” who are planning to make Britain great again. The narrator’s antagonism to them is clear enough – the poem enjoys mocking their “banal resentments”, their abortive calls to phone-in radio shows, their “bigotry” – but the moral stance is complicated by his inability directly to confront such attitudes, though he acknowledges that he should: “Too bored to laugh, too tired to cry, you think / These people do not matter. Then they do”. Here too, the “you” does a great job of skewering the complacent reader.

O’Brien’s smokingly apocalyptic visions, familiar from earlier collections, recur in Europa, though (again) to pin these to the shameful, self-wounding moment of Brexit is surely too reductive. ‘Apollyon’ is a scary vision of destructive power as a “[g]ent of an antiquarian bent” and ‘Exile’ relishes the blunt pessimism of its given-and-snatched-away conclusion: “It is from here, perhaps, that change must come. / You are garrotted by a man your hosts have sent”. One of the instigators of betrayal and disaster, in what begins to heap up in the book as a modern wasteland, is recognisable in her “leopard shoes and silver rings” and it feels particularly pointed that O’Brien has to go as far as Mexico City (and a more mythopoetic mode) to find a strange man/beast at a bar who suggests the possibility of “living in hope despite the mounting evidence” (‘Jaguar’).

As I have already hinted, the equivocal role of the artist has long bothered O’Brien and – it’s my impression – that he beats himself up more frequently nowadays over the poet/artist’s impotence. The hilarious but ultimately cynical account in ‘Sabbatical’ of university life (especially Creative Writing) paints a depressing scene:

Apres moi, Creative Writing, dammit.

Good luck, my friends, my enemies,

And those of you to whom in all these years

I’ve still not spoken. Now I bid farewell,

Abandoning my desk, my books

And thirteen thousand frantic e-mails

Enquiring about the Diary Exercise

On which the fate of everything

(To whit, this institution) hangs

The collection ends with ‘A Closed Book’, a poem which has clear echoes of Shelley’s apocalyptic, unfinished last poem, ‘The Triumph of Life’. Someone – it’s “you”, of course – impotently watches a parade (“a cart”) rolling through an unspecified European square where he is sitting like a tourist (or someone on a sabbatical). The figure does little other than observe and wait, “As if this one venue would give you / The secret entire”. But here too, the knives are elegantly brought out. It is for such a moment “you spent your life preparing”, we are told, and though hopes of “transfiguration” and “perfection” are voiced, the sense is more of an exhausted spirit, of self-delusion.

Europa is full of such unflinching, incisive moments, combined with a breadth of vision and dark sense of humour that few contemporary poets can match. But I worry that in so frequently denigrating his own art (ironically because he expects so much ‘achievement’ from it), O’Brien ironically runs the risk of allowing darker agencies too much influence in a culture that, for its many faults, permits a high degree of liberal civilisation. A civilisation, in the interstices of which (at the risk of sounding too complacent), pass lives of relative peace and achievement, where even art with fewer explicit political designs should be lauded and encouraged, since it too plays an ethical/political role, as if to say, ‘this is what must be protected’.

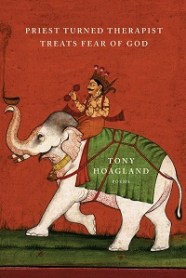

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).

The next section of the poem displays some of Lorca’s startling, surprising images: the “stars of frost”, the “fish of shadows”, the fig-tree’s “sandpaper branches”, the mountain is a “a thieving cat” that “bristles its sour agaves”. These are good examples of Lorca’s technique with metaphor: to place together two things which had always been considered as belonging to two different worlds, and in that fusion and shock to give them both a new reality. But these lines are perhaps really more about raising the narrative tensions in the poem through rhetorical questions such as, “But who will come? And where from?”

The next section of the poem displays some of Lorca’s startling, surprising images: the “stars of frost”, the “fish of shadows”, the fig-tree’s “sandpaper branches”, the mountain is a “a thieving cat” that “bristles its sour agaves”. These are good examples of Lorca’s technique with metaphor: to place together two things which had always been considered as belonging to two different worlds, and in that fusion and shock to give them both a new reality. But these lines are perhaps really more about raising the narrative tensions in the poem through rhetorical questions such as, “But who will come? And where from?” So up they climb. We don’t know why, but the atmosphere here is dripping with ill omen: they are “leaving a trail of blood, / leaving a trail of tears”. Then there is another of Lorca’s images yoking together unlikely items. As they climb to the roof-tiles, there is a trembling or quivering of “tiny tin-plate lanterns” and perhaps it’s this that becomes the sound of a “thousand crystal tambourines / [that] wound the break of day”. Lorca himself chose this image to comment on in his talk. He says if you ask why he wrote it he would tell you: “I saw them, in the hands of angels and trees, but I will not be able to say more; certainly I cannot explain their meaning”. I hear Andre Breton there, or Dali refusing to ‘explain’ the images of the truly surreal work. In each case the interpretative labour is handed over to us.

So up they climb. We don’t know why, but the atmosphere here is dripping with ill omen: they are “leaving a trail of blood, / leaving a trail of tears”. Then there is another of Lorca’s images yoking together unlikely items. As they climb to the roof-tiles, there is a trembling or quivering of “tiny tin-plate lanterns” and perhaps it’s this that becomes the sound of a “thousand crystal tambourines / [that] wound the break of day”. Lorca himself chose this image to comment on in his talk. He says if you ask why he wrote it he would tell you: “I saw them, in the hands of angels and trees, but I will not be able to say more; certainly I cannot explain their meaning”. I hear Andre Breton there, or Dali refusing to ‘explain’ the images of the truly surreal work. In each case the interpretative labour is handed over to us. Did they know this? It appears not. But who is she? Daughter? Lover? Both? Is this really what the two men find there? For sure, there is some mystery about the chronology because the seeming explanation of the killing is couched as a flashback: “The dark night grew intimate / as a cramped little square. / Drunken Civil Guards / were hammering at the door”. But Lorca often plays fast and loose with verb tenses. Was this earlier? Were they in search of the rebellious youth? But they found his girl-friend? Hanging her on the rooftop? Is the house owner her father? Does he know what has happened? Is this why his house is not his own anymore? Is this why he is no more what he was?

Did they know this? It appears not. But who is she? Daughter? Lover? Both? Is this really what the two men find there? For sure, there is some mystery about the chronology because the seeming explanation of the killing is couched as a flashback: “The dark night grew intimate / as a cramped little square. / Drunken Civil Guards / were hammering at the door”. But Lorca often plays fast and loose with verb tenses. Was this earlier? Were they in search of the rebellious youth? But they found his girl-friend? Hanging her on the rooftop? Is the house owner her father? Does he know what has happened? Is this why his house is not his own anymore? Is this why he is no more what he was? The only certain thing is that the poem does not reply. It ends with a recurrence of that opening yearning – now it’s read as a more obviously grieving voice – though it’s not necessarily to be read as the young man’s voice. It’s the ballad voice, the one I took so long to really grasp in Lorca’s work. It is a voice involved and passionate but with wider geographical, political and historical horizons beyond the individual incident. Like Auden’s ploughman in ‘Musee des Beaux Arts’, glimpsing Icarus’ fall from the sky, yet he must get on with his work, ‘Sleepingwalking Ballad’ returns us in its final lines to the wider world:

The only certain thing is that the poem does not reply. It ends with a recurrence of that opening yearning – now it’s read as a more obviously grieving voice – though it’s not necessarily to be read as the young man’s voice. It’s the ballad voice, the one I took so long to really grasp in Lorca’s work. It is a voice involved and passionate but with wider geographical, political and historical horizons beyond the individual incident. Like Auden’s ploughman in ‘Musee des Beaux Arts’, glimpsing Icarus’ fall from the sky, yet he must get on with his work, ‘Sleepingwalking Ballad’ returns us in its final lines to the wider world:

I really didn’t know it at the time, but the song’s words are, of course, by W.B. Yeats. It is his poem ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’, from The Wind Among the Reeds (1899).

I really didn’t know it at the time, but the song’s words are, of course, by W.B. Yeats. It is his poem ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’, from The Wind Among the Reeds (1899). I have now translated a number of Lorca’s poems and one of the great difficulties is to carry over such metaphorical leaps into English where they risk sounding very silly indeed. Fair enough, the alligator is, on the face of it, obvious enough: its gaping jaws give a good jolt of comic hyperbole to his image. But it’s still surprising in the context of a be-suited, bespectacled lecture hall in Spain. There is an exoticism there on the verge of surrealism and is characteristic of Lorca’s images. This search for novelty in image is clear when he argues later that a real poet must “shoot his arrows at living metaphors and not at the contrived and false ones which surround him”.

I have now translated a number of Lorca’s poems and one of the great difficulties is to carry over such metaphorical leaps into English where they risk sounding very silly indeed. Fair enough, the alligator is, on the face of it, obvious enough: its gaping jaws give a good jolt of comic hyperbole to his image. But it’s still surprising in the context of a be-suited, bespectacled lecture hall in Spain. There is an exoticism there on the verge of surrealism and is characteristic of Lorca’s images. This search for novelty in image is clear when he argues later that a real poet must “shoot his arrows at living metaphors and not at the contrived and false ones which surround him”.

Just one last detail from this great poem. Juan Antonio de Montilla is killed in the fight and – in one of Lorca’s characteristic jump cut edits (more of that in a minute) suddenly (it seems) the “judge and Civil Guard / come through the olive groves”. Somebody – a participant, one of the old women? – gives them an account of events in the form of exactly one of Lorca’s startling metaphors. This may have been a quarrel over a card game, or a girl, like so many others, but Lorca dizzyingly elevates it into an historical, even epic context:

Just one last detail from this great poem. Juan Antonio de Montilla is killed in the fight and – in one of Lorca’s characteristic jump cut edits (more of that in a minute) suddenly (it seems) the “judge and Civil Guard / come through the olive groves”. Somebody – a participant, one of the old women? – gives them an account of events in the form of exactly one of Lorca’s startling metaphors. This may have been a quarrel over a card game, or a girl, like so many others, but Lorca dizzyingly elevates it into an historical, even epic context:

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

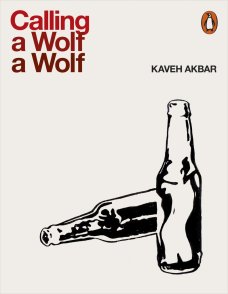

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

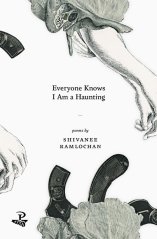

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

You will have gathered that one of Power’s things is to mix English and Austrian German. This happens several times in ‘A Tour of Shrines of Upper Austria’ (though in this book we only get 7 parts of the full sequence). An observer stops at various shrine sites, jotting down some thoughts and taking a picture or two. Nothing is developed though Power’s poems do show an interest in religion on several other occasions. ‘The Moving Swan’ opens with a centre-justified prose description of candles flickering in a cathedral and another poem is drawn to the grave of two goats, observing: “two heaps of ivy/straw / one unlit red tealight”. And ‘Epiphany Night’ is a more extended series of notes recording a local celebration with bells, dressing-up, boats, lanterns. This is all observed in loosely irregular lines by the narrator from her “wohnung” (apartment). To wring all engagement or emotional or imaginative response from such a text is, I suppose, quite an achievement but to spend 70-odd pages in such company really is wearisome.

You will have gathered that one of Power’s things is to mix English and Austrian German. This happens several times in ‘A Tour of Shrines of Upper Austria’ (though in this book we only get 7 parts of the full sequence). An observer stops at various shrine sites, jotting down some thoughts and taking a picture or two. Nothing is developed though Power’s poems do show an interest in religion on several other occasions. ‘The Moving Swan’ opens with a centre-justified prose description of candles flickering in a cathedral and another poem is drawn to the grave of two goats, observing: “two heaps of ivy/straw / one unlit red tealight”. And ‘Epiphany Night’ is a more extended series of notes recording a local celebration with bells, dressing-up, boats, lanterns. This is all observed in loosely irregular lines by the narrator from her “wohnung” (apartment). To wring all engagement or emotional or imaginative response from such a text is, I suppose, quite an achievement but to spend 70-odd pages in such company really is wearisome.

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”.

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”. For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?

For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?

Then I have been reading poems for Grenfell Tower (The Onslaught Press) and picking away at some link between the (in)adequacy of a certain English poetic voice to confront the scale of ecological issues, or as a vehicle for expressing certain cultural differences, or as a way of exploring the kind of tragic and grievous event represented by the Grenfell fire and its aftermath. This struck me particularly as, in the Grenfell anthology, there are well-know poets alongside others less well-known, plus some who felt impelled to write as a direct result of the catastrophe. I felt many of the more well-known names struggled to find a sufficient voice for this appalling event, often sounding too careful, overly subtle, perhaps too concerned with Mort’s “linguistic originality”. Does such a devastating, large scale, well publicised event require a different kind of voice from poets?

Then I have been reading poems for Grenfell Tower (The Onslaught Press) and picking away at some link between the (in)adequacy of a certain English poetic voice to confront the scale of ecological issues, or as a vehicle for expressing certain cultural differences, or as a way of exploring the kind of tragic and grievous event represented by the Grenfell fire and its aftermath. This struck me particularly as, in the Grenfell anthology, there are well-know poets alongside others less well-known, plus some who felt impelled to write as a direct result of the catastrophe. I felt many of the more well-known names struggled to find a sufficient voice for this appalling event, often sounding too careful, overly subtle, perhaps too concerned with Mort’s “linguistic originality”. Does such a devastating, large scale, well publicised event require a different kind of voice from poets? The difficulties of addressing such a subject are expressed by Joan Michelson’s contribution which announces and extinguishes itself in the same moment: “This is the letter to the Tower / that I cannot write”. One of the best poems which does display evident ‘literary’ qualities is Steven Waling’s ‘Fred Engels in the Gallery Café’. It cleverly splices several voices or narratives together, one of these being quotes from Engels’ 1844 The Condition of the Working Class in England. Other fragments used allude to gentrification and the wealth gap in the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Other poems, like Pat Winslow’s ‘Souad’s Moon’, focus on the presence of refugees in the Tower, or the role of the profit-motive in the disaster (‘High-Rise’ by Al McClimens), or the presence of an establishment cover-up after the event (Tom McColl’s ‘The Bunker’).

The difficulties of addressing such a subject are expressed by Joan Michelson’s contribution which announces and extinguishes itself in the same moment: “This is the letter to the Tower / that I cannot write”. One of the best poems which does display evident ‘literary’ qualities is Steven Waling’s ‘Fred Engels in the Gallery Café’. It cleverly splices several voices or narratives together, one of these being quotes from Engels’ 1844 The Condition of the Working Class in England. Other fragments used allude to gentrification and the wealth gap in the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Other poems, like Pat Winslow’s ‘Souad’s Moon’, focus on the presence of refugees in the Tower, or the role of the profit-motive in the disaster (‘High-Rise’ by Al McClimens), or the presence of an establishment cover-up after the event (Tom McColl’s ‘The Bunker’). But more often than not, these poets opt for more tangential routes to expression. Other disasters – such as Nero watching Rome burn, the 1666 Fire of London, the bomb falling on Hiroshima and the Aberfan disaster – prove ways in for Abigail Elizabeth Rowland, Neil Reeder, Margaret Beston and Mike Jenkins. The naivety and innocence of a child’s eye is another common device. Andrew Dixon’s ‘Storytime’ takes this approach, the child’s language and vision allowing simple but nevertheless powerful statements: “Mama don’t be afraid. Do you / want us to pray? I know what / to say. We’re both in a rocket / and we’re going away.” Finola Scott does the same with a Glasgow accent, a child staring from her own tower block home: “she peers doon at hir building, wunners / Whit’s cladding?’ A young life cut off before its full development by the fire is also the theme of two poems that refer to the death of Khadija Saye. She was a photographer who died in the blaze, whose work had been exhibited in Britain’s Diaspora Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Michael Rosen’s contribution again uses childlike simplicity and obsessive repetition – as much representing a struggle to comprehend as the gnawing of realised grief:

But more often than not, these poets opt for more tangential routes to expression. Other disasters – such as Nero watching Rome burn, the 1666 Fire of London, the bomb falling on Hiroshima and the Aberfan disaster – prove ways in for Abigail Elizabeth Rowland, Neil Reeder, Margaret Beston and Mike Jenkins. The naivety and innocence of a child’s eye is another common device. Andrew Dixon’s ‘Storytime’ takes this approach, the child’s language and vision allowing simple but nevertheless powerful statements: “Mama don’t be afraid. Do you / want us to pray? I know what / to say. We’re both in a rocket / and we’re going away.” Finola Scott does the same with a Glasgow accent, a child staring from her own tower block home: “she peers doon at hir building, wunners / Whit’s cladding?’ A young life cut off before its full development by the fire is also the theme of two poems that refer to the death of Khadija Saye. She was a photographer who died in the blaze, whose work had been exhibited in Britain’s Diaspora Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Michael Rosen’s contribution again uses childlike simplicity and obsessive repetition – as much representing a struggle to comprehend as the gnawing of realised grief: