I knew Mary MacRae as a member of a poetry workshop we both attended in north London. She came to writing poetry late and published just two collections – As Birds Do (2007) and (posthumously) Inside the Brightness of Red (2010) both from Second Light Publications. Her poem ‘Jury’ was short-listed for the Forward single poem prize and was re-published in the Forward anthology, Poems of the Decade (2011). That anthology is now set as an A Level text and it was through teaching from it recently that Mary’s work came back to mind.

Mary died in 2009 at the age of 67. As a writer she was just beginning to hit her stride. Mimi Khalvati praises her as “a poet of the lyric moment in all its facets” and judges Mary’s ten years of work as an “extraordinarily coherent” body of poems. Khalvati goes on: “Because of the natural ease and grace of her diction, it would be easy to overlook Mary’s versatile formal skills, employed in sonnets, syllabics (à la Marianne Moore), numerous stanzaic forms, but nowhere evidenced more forcefully than in her ‘Glose’ poem, inspired by Marilyn Hacker’s examples, in which she pays homage to Alice Oswald, as in a previous glose to Mary Oliver – a trinity of wonderful lyric poets, in whose company Mary, modest but not lacking in ambition, shyly holds her own.”

In 2009/10 many friends and writers contributed pieces in memory of Mary to the magazine Brittle Star. Most of this material can now be found here with prose contributions from Jacqueline Gabbitas, Myra Schneider, Lucy Hamilton and Dilys Wood. I wrote a poem at the time (remembering meetings of the poetry workshop in London) and I have more recently revised it more than a little. I’m posting it here alongside the review I wrote of Mary’s posthumous collection with the idea of making the review more easily available and perhaps encouraging others to seek out Mary’s published work.

Before the rain arrives

i.m. Mary MacRae

Perhaps five or six of us standing there

at the familiar purple door

those afternoons we lost beneath poetry’s

red weather our voices and lines

while the genuine thing built unremarked

beyond the window’s diamond panes

till it was time to depart

then our turning back in the familiar porch

our repeated goodbyes being called

our uncertain bunching

that coheres and delays until one of us

breaks loose and we are each free to disperse—

yet on that day there were raindrops

on the back of a hand on another’s cheek

and though we fiddled with car keys

we fidgeted in trainers and faded jeans

we were an ancient chorus for a moment

crying the single syllable

the drawn-out sound of r—a—i—n

because we were weary of weeks of drought

and now it came and we saw where it fell

the raindrops beginning

to shrill their high-pitched release

from interlaced shadows

from the skirts of clouds

and what none of us knew until we’d seen

one more year was that one of us there

despite our sharp eye for openings

and endings would have to face last things

like the white vanishing of panicked doves

into dark thunderheads—

on these more recent afternoons

just four or five of us here perhaps

in our minds her shrewd observations

her words urging us closer to listen

for the noise rain makes before the rain arrives

Review: Mary MacRae, Inside the Brightness of Red (Second Light Publications, 2010), 96pp, £8.95, ISBN 978-0-9546934-8-0

Mary MacRae’s 2007 debut collection was titled As Birds Do. It is true that birds feature variously in that and this, her sadly posthumous new collection, but if we are unaware of the earlier title’s provenance, we might anticipate no more than a delicate, poetic take on the natural world, the kind of thing that fills so many small magazines. But MacRae alludes to the moment in Macbeth, when Lady Macduff and her son contemplate death. The mother asks, “How will you live?” and the son, with a wisdom far beyond his years, replies, “As birds do Mother . . . . With what I get I mean”. MacRae’s poetry is full of such emotionally-charged, vital identifications with natural creatures and, more profoundly, with the sense that what can sustain us in life must be derived from everyday common objects.

As a title, Inside the Brightness of Red, also flirts a little with poetic affectation, but once inside the book’s covers, it is MacRae’s precise, even astringent, penetration that is so impressive. She reads the world around her and finds spiritual meanings. It is no surprise that R.S. Thomas supplies the epigraph to this new collection: “It is this great absence / that is like a presence, that compels / me to address it without hope / of a reply”. So a poem called ‘Yellow Marsh Iris’ promises to be a naturalist’s observation then startlingly wrong-foots the reader with its opening line (“It’s how I imagine prayer must be”) and proceeds to its seamless business of combining accuracy of observation with an emotional and intellectual narrative. She studies the flower stems crammed into a glass vase:

their stiff stems magnified

by water, criss-crossing

white, pale green, green

in a shadowy coolness

We are reminded that there is a kind of intensity of observation that succeeds in prising open our relationship with the outer world in such a way that while encountering the Other, we more clearly glimpse ourselves. MacRae concludes her process of “looking and looking” at the flowers that has given rise to the sense that “they seem to hold / all words, all meaning, / and what I’m reading / is a selving, a creation.”

MacRae’s visions are almost always peripheral, fleeting, askance. The unfolding of daffodils – which, in a quite different age, Wordsworth could contemplate steadily and then stow away for future use – here can never be more than something

waiting for us somewhere in the wings

like angels,

your darting after-image

between the pear-tree

and the brick wall.

(‘Daffodils’)

In the same vein, MacRae has Bonnard, paint his mistress, Marthe de Meligny, and declare that his sensibility is triggered by “looking askew”. The visionary moment occurs only when “Glimpsed through the half-open door / or the crack of the hinge-gap” (‘Bonnard to Marthe’) and this collection’s editors (Myra Schneider and Dilys Wood) have drawn it to a close with yet another such moment: “Turning back to look through an open door” the narrator sees an ordinary room “utterly transformed, / drained dry and clear, unweighted” (‘Un-Named’).

It may be that this ability to be sustained by scraps and glimpses, the sense that the self is most fully resolved in a lack of egotism, in its encounter with ordinary things, can diminish some of the sting of mortality. In a poem like ‘White’, MacRae manages to celebrate again the ordinariness of familiar things while at the same time sustaining a contentedness (or at least an absence of fear) at the prospect of the self’s vanishing: “You can disappear in a house where / you feel at home; the rooms are spaces / for day-dreams, maps of an interior / turned inside out”. Rather than Macbeth, it is Hamlet’s resolve to “let be” that comes to mind as this calm, accessible, colourful and wonderfully dignified poem concludes:

It may be that this ability to be sustained by scraps and glimpses, the sense that the self is most fully resolved in a lack of egotism, in its encounter with ordinary things, can diminish some of the sting of mortality. In a poem like ‘White’, MacRae manages to celebrate again the ordinariness of familiar things while at the same time sustaining a contentedness (or at least an absence of fear) at the prospect of the self’s vanishing: “You can disappear in a house where / you feel at home; the rooms are spaces / for day-dreams, maps of an interior / turned inside out”. Rather than Macbeth, it is Hamlet’s resolve to “let be” that comes to mind as this calm, accessible, colourful and wonderfully dignified poem concludes:

Let

it all go; soon the door of your room

will be locked, leaving only a slight

hint of you still, a ghostly perfume

lingering in the threadbare curtains and sheets.

But MacRae’s contemplation of her own death, most likely, was no such safely distanced envisaging. Dying at 67 years old, she’d had only 10 years of writing poetry, but it had evidently become a vessel into which she could pour her experience without ever abandoning herself to artistic ill-discipline. ‘Prayer’ is almost too painful to read. The narrator is emerging from the “thick dark silt” of anaesthetic to hear someone sobbing and a second voice trying to offer comfort. As her befuddled perceptions clear and the poem’s tight triplet form unfolds, the second voice is understood to be saying “’Don’t cry, Mary, / there’s no need to cry’”. The collection’s title poem can bluntly report that “the cancer’s come back” yet artfully balances such devastating news with the landscape of Oare Marsh in Kent where colours “are so spacious, / and have such depth they’re like lighted rooms // we could go into” (‘Inside the Brightness of Red’).

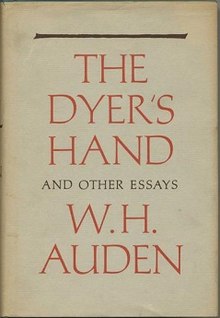

For MacRae’s interest in and skill with poetic form, we need look no further than the extraordinary glose on a quatrain from Alice Oswald (the earlier collection contained another on lines from Mary Oliver). For most poets, this form is little more than an exhibitionist high-wire act, but MacRae’s poems are moving and complete. Her use of poetic form here, particularly in some of these last poems, reminds me of Tony Harrison’s conviction that its containment “is like a life-support system. It means I feel I can go closer to the fire, deeper into the darkness . . . I know I have this rhythm to carry me to the other side” (Tony Harrison: Critical Anthology, ed. Astley, Bloodaxe Books, 1991, p.43). Appropriately, in ‘Jar’, she contemplates with admiration an object that has “gone through fire, / risen from ashes and bone-shards / to float, nameless, into our air”. Here, the narrator movingly lays aside the wary scepticism of the Thomas epigraph and rests her cheek on the jar’s warmth to “feel its gravity-pull / as if it proved the afterlife of things”.

For MacRae’s interest in and skill with poetic form, we need look no further than the extraordinary glose on a quatrain from Alice Oswald (the earlier collection contained another on lines from Mary Oliver). For most poets, this form is little more than an exhibitionist high-wire act, but MacRae’s poems are moving and complete. Her use of poetic form here, particularly in some of these last poems, reminds me of Tony Harrison’s conviction that its containment “is like a life-support system. It means I feel I can go closer to the fire, deeper into the darkness . . . I know I have this rhythm to carry me to the other side” (Tony Harrison: Critical Anthology, ed. Astley, Bloodaxe Books, 1991, p.43). Appropriately, in ‘Jar’, she contemplates with admiration an object that has “gone through fire, / risen from ashes and bone-shards / to float, nameless, into our air”. Here, the narrator movingly lays aside the wary scepticism of the Thomas epigraph and rests her cheek on the jar’s warmth to “feel its gravity-pull / as if it proved the afterlife of things”.

This inspiring collection contains a short Afterword by Mimi Khalvati who MacRae frequently praised as a critical figure in her work’s development. Khalvati lauds her as “a poet of the lyric moment in all its facets”. She judges MacRae’s ten years work as an “extraordinarily coherent” body of poems, suggesting that, among the likes of Oswald and Oliver, MacRae’s work is “modest but not lacking in ambition”. For me, her two collections certainly exhibit a modesty before the world of nature that is really a genuine humility, allowing both the physical and spiritual worlds to flower in her work. This was her true ambition, pursued in full self-awareness and one that, before her sad leaving, she had triumphantly fulfilled.

*As a labouring translator myself, I have long remembered Grigson’s brilliant put-down in his Introduction to the Faber Book of Love Poems (1973). Explaining why he has not included any translations at all, he declares that their “unmeasured, thin-rolled short crust” would prove detrimental to the health of the nation’s poetic taste. Times have changed, thank goodness.

*As a labouring translator myself, I have long remembered Grigson’s brilliant put-down in his Introduction to the Faber Book of Love Poems (1973). Explaining why he has not included any translations at all, he declares that their “unmeasured, thin-rolled short crust” would prove detrimental to the health of the nation’s poetic taste. Times have changed, thank goodness.

.

.

![1074-Poetry-Review_Cover-RGB-300-w-shadow-429x600[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1074-poetry-review_cover-rgb-300-w-shadow-429x6001.jpg?w=199&h=279)

![jellyfish[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jellyfish1.jpg?w=700)

![alpine-skiing-877410_640[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/alpine-skiing-877410_6401.jpg?w=348&h=261)

![DKKnm3zX0AAbJg_[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/dkknm3zx0aabjg_1.jpg?w=360&h=385)

![Lee-Miller[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/lee-miller1.jpg?w=276&h=368)

![Collaborators[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/collaborators1.jpg?w=366&h=245)

![486434472_f02117992d_o[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/486434472_f02117992d_o1.jpg?w=247&h=288)

![Saphra-interview[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/saphra-interview1.jpg?w=700)

![lee_miller_biography_beautiful_young_thing_audacious_muse_photographer_3l[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/lee_miller_biography_beautiful_young_thing_audacious_muse_photographer_3l1.jpg?w=573&h=322)

![DM-HkzHWkAAx8CG[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/dm-hkzhwkaax8cg1.jpg?w=288&h=407)

![laocoon[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/laocoon1.jpg?w=256&h=335)

![8226eece-e840-4378-9fb4-cd24af13aef4[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/8226eece-e840-4378-9fb4-cd24af13aef41.jpg?w=358&h=229)

![DLRftRFW4AAtwJQ[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/dlrftrfw4aatwjq1.jpg?w=405&h=270)

![making-ends-meet-cover[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/making-ends-meet-cover1.jpg?w=225&h=293)

![182712359-a2163bed-2fd9-4910-9e04-673d2bb611ef[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/182712359-a2163bed-2fd9-4910-9e04-673d2bb611ef1.jpg?w=357&h=226)