This review is an extended version of the one which first appeared in Acumen Poetry Magazine in the autumn of 2025. Many thanks to the reviews editor, Andrew Geary, for commissioning it.

Considered by Thomas Mann as ‘the first lady of German letters’ and as the first woman to receive the prestigious Goethe Award (1931), Ricarda Huch (1864-1947) was a literary superstar of her time, yet remains little known in English. She was an historian who published novels, philosophy, drama and poetry. With the rise of Hitler, she made her rejection of Nazi doctrine clear, remaining in Germany as an ‘inner émigré’, but surviving the war years. Autumn Fire (Poetry Salzberg, 2024) is her last collection, published in 1944, and powerfully reflects her lifelong fascination with the Romantic movement. As Karen Leeder’s scene-setting Introduction explains, this is evidenced in the poems’ formal choices as well as imagery, ‘a repertoire of sprites, flowers, scents, birdsong, gardens, moons, fairy tales, and love’. An English poetry reader would initially place this work in parallel to the least challenging of the Georgian poets of 1914.

There is frequently a faux medievalism at work, as in ‘The trees of autumn murmur’ which tells the story of a Prince who wanders into the woods and is bewitched by ‘fairies wild’ to live a sad, unloving, unhappy life. Other poems remind us of Hardy’s folkloric, time-obsessed lyrics in similarly challenging stanza forms:

On far-off floors the dancers face the middle,

The hems swing stiffly to the threshers’ drum.

Accordion and bass and fiddle

Ethereal hum.

(‘Autumn’)

Also from the stock Romantic image bank comes the isolated, tortured figure of the poet who, as spring days arrive, remains unmoved by them because mysteriously ‘troubled’ and when called upon to sing his songs (this is Huch’s own masculine gendering), finds that his creative efforts are ‘unwelcome’ to society at large (‘Morning of twittering birds’).

However, a closer reading of Huch’s poems clarifies their curiously hybrid effects, as in ‘The Old Minstrel’ in which the violent early years of the twentieth century come forward dressed in medieval garb. The narrative voice encourages the minstrel to sing and play his harp: ‘songs of golden treasure, / Times of playfulness and pleasure’. But the final lines of the poem are spoken (we must assume) by the minstrel who warns that what may come from him demands powerful trigger warnings:

Woe betide ye when I call

Forth my lions, every string,

Dumb in dusty ambuscade,

Torpid now, glistening

Thick with matted blood!

Huch boldly leaves the poem there, without any return to a possibly moderating, narrative voice. ‘The Heroes’ Tomb’ also makes use of familiar images (a tomb, a blustery November day, an old man, a passing shepherd, a youngster asking questions) to address a distanced ‘wicked war’. This poem similarly ends bloodily (though note, we are still in the era of swords rather than machine guns), as those who are inclined to stoop and listen at the tomb, can ‘make out far below the clash of swords, / And tell the drip, drip, drip, and hear the sound. / Can it be blood?’

Such lines contrast the lark’s song, the perfumed jasmine, the poplars and lime trees inhabiting so many of these pages and Huch herself seems to shuttle between a religious-based optimism and a much more modern sounding despair. In ‘Moonlit Night’, an owl flies through a wood and takes a mouse as prey. The moon seems to be portrayed as looking on, wholly indifferent, as it picks its way through the branches, ‘twinkle-toed and light’. Only the form and language here makes the poem feel less than genuinely Modern. As for the owl, it becomes proleptic of technological advances in air warfare as she sweeps off through the wood, ‘the murderess, / whose claws the victim hold, / airborne above black treetops’ emptiness’. Another predator image later provides the reader with a further shock. In ‘My heart, my lion, grasps its prey’, the latter is identified as ‘the hated’. And the passionate nature of Huch’s antagonism – though the object of her hate is never named – is startling, and she uses repetition, shortened lines and rhyme to make her point:

My heart hates yet the hated,

My heart holds fast its prey,

That none may palter or gainsay,

No liar gild the worst,

Nor lift the curse from the accursed.

Almost inevitably you feel, the elements of modern warfare seep into Huch’s poems. In the midst of another Hardyesque stanzaic poem, between the ‘honey-brown’ buds on the trees and the lark’s ‘music-making’, more familiar ‘war poem’ sounds provide the base notes: ‘The earth shakes with battle, the air with shellfire heaves’ (‘War Winter’). The ABAB quatrains of ‘The Young Fallen’ mourn those taken by war by first evoking the innocence of their childhoods, schooldays, their unfulfilled worldly ambitions. Then ‘War came’. And though much of the detail and imagery could be applied to wars fought anytime in the last few centuries, there are moments when the realities of the mid-twentieth century cannot be denied. The young men’s hands are a focus, as they ‘Not long ago reached out for toys and fun. / Those hands, conversant with the tools of murder, / Control the howitzer and grip the gun’.

In fact, Huch was living in Jena when the city was bombed by the Allies and ‘The Flying Death’ comes closer than any other poem in conveying her experiences of modern warfare. Though the Flying Death is an old-fashioned personification, its modus operandi is up to date: ‘The chimney reels, the roof-beams groan, / By distant thunder he is known’. Even as the air bombardment is imaged as approaching on ‘iron steeds’, its impact is plainly conveyed as ‘A whistling, hissing din, and more, / A jarring shriek is heard, a roar, / As if the earth would burst.’ This Poetry Salzberg publication unfortunately does not give the reader the original German, but Timothy Adès’ translations are quite brilliant in their preservation of form and rhyme, while at the same time conveying both the sweetness and the violence in Huch’s curious, powerful, under-appreciated poetry.

Excerpts from Autumn Fire, tr. Timothy Adès

Stralsund

The old grey town that blue sea girds:

The swell of rust-red sails,

The squawking, tumbling salt-sea birds,

The flash of clean fish-scales.

On this church wall the pounding wave

And tempest waste their fire:

Though organ-thunder shakes the nave,

No foe hurls down the spire.

The clouds with tender beating wing

Caress its head, that dreams

Of fierce-fought battles reddening

Its foot with gory streams.

The dead are sleeping, stone by stone,

The sounding bells request:

Eternal memory, my son,

Be thine, eternal rest!

Music

Melodies heal up our every smart;

Happiness,

Lost to us, they redress;

They are balsam to our ailing heart.

From the earth where we without respite

Toil enslaved,

As on wings of blessed angels saved

They transport us to a land of light.

Sound, sound forth, ye songs of mystery!

Worlds fly far;

Earth sinks down, our red and bloodstained star;

Love distils its essence from on high.

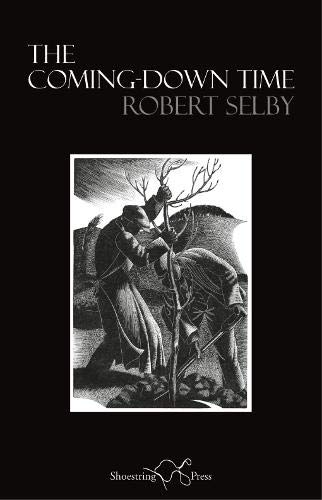

Robert Selby’s debut collection is fronted by a wood cut engraving by Clare Leighton, titled ‘Planting Trees’. Two flat-capped workmen labour to bed in a sapling. A wind-bent tree stands nearby; on the gusty skyline, at the top of a hill, a dark copse. It’s like something out of a Thomas Hardy poem, or an Edward Thomas one, and it’s well-chosen as these are the forebears The Coming-Down Time often explicitly acknowledges. Launched into a poetry world dominated by so many books addressing environmental, gender, race and identity issues, this collection (depending on your viewpoint) is either timeless or behind the times. Selby’s careful organisation of the poems makes it clear he knows what he’s doing and he will do it his way.

Robert Selby’s debut collection is fronted by a wood cut engraving by Clare Leighton, titled ‘Planting Trees’. Two flat-capped workmen labour to bed in a sapling. A wind-bent tree stands nearby; on the gusty skyline, at the top of a hill, a dark copse. It’s like something out of a Thomas Hardy poem, or an Edward Thomas one, and it’s well-chosen as these are the forebears The Coming-Down Time often explicitly acknowledges. Launched into a poetry world dominated by so many books addressing environmental, gender, race and identity issues, this collection (depending on your viewpoint) is either timeless or behind the times. Selby’s careful organisation of the poems makes it clear he knows what he’s doing and he will do it his way.

Selby’s use of language and form is likewise pretty traditional. It’s not just a result of the subject matter that the book is frequented by words such as smithy, shire, lambkin, deer-stalker, and lush-toned phrases such as “blossom-moted”. The flip side of this is that details of 2020 UK are often treated with a distaste, an alienated distance. Later in the book, a friend returns from the dust and pollen of the English countryside into London: “its tagged shutters and sick-flecked stops, / its scaffolding like the lies / propping up your peeling hopes”. The friend is female and (I think) Canadian. Another poem’s narrator tries to persuade her that “[t]his is the real England [. . .] It’s a place of trees; of apple, pear, cherry and plum”. There is more to be said here about the meaning of ‘real’ and it’s hard to tell if the narrator’s invitation is meant to have a deathly ring to it. He asks, “Do you want to reset your watch to the toll of here?”

Selby’s use of language and form is likewise pretty traditional. It’s not just a result of the subject matter that the book is frequented by words such as smithy, shire, lambkin, deer-stalker, and lush-toned phrases such as “blossom-moted”. The flip side of this is that details of 2020 UK are often treated with a distaste, an alienated distance. Later in the book, a friend returns from the dust and pollen of the English countryside into London: “its tagged shutters and sick-flecked stops, / its scaffolding like the lies / propping up your peeling hopes”. The friend is female and (I think) Canadian. Another poem’s narrator tries to persuade her that “[t]his is the real England [. . .] It’s a place of trees; of apple, pear, cherry and plum”. There is more to be said here about the meaning of ‘real’ and it’s hard to tell if the narrator’s invitation is meant to have a deathly ring to it. He asks, “Do you want to reset your watch to the toll of here?” The import of this question forms the emotional and dramatic context of the later poems in the collection which trace an on/off relationship. The narrator is left wondering: “I must wait for the needle / of your heart’s compass to unspin, / and see where it stops”. In reading that I’m reminded of Lea and – what seemed to be – her relative lack of choice in the earlier years of the twentieth century. There is a good deal of unalloyed nostalgia in The Coming-Down Time for an England of the mind, if it was ever part of any actual century. I find the female figures in the book suffer because of this: most of them do not achieve a specific, particular life in the poems. I’d like Selby to go on to explore the irony in two images: the masculine arms in “rolled up sleeves” that may or may not be “strong enough” and the closing lines just quoted, in which the desired woman bides her time, knowingly possessed of strength, of the agency of decision.

The import of this question forms the emotional and dramatic context of the later poems in the collection which trace an on/off relationship. The narrator is left wondering: “I must wait for the needle / of your heart’s compass to unspin, / and see where it stops”. In reading that I’m reminded of Lea and – what seemed to be – her relative lack of choice in the earlier years of the twentieth century. There is a good deal of unalloyed nostalgia in The Coming-Down Time for an England of the mind, if it was ever part of any actual century. I find the female figures in the book suffer because of this: most of them do not achieve a specific, particular life in the poems. I’d like Selby to go on to explore the irony in two images: the masculine arms in “rolled up sleeves” that may or may not be “strong enough” and the closing lines just quoted, in which the desired woman bides her time, knowingly possessed of strength, of the agency of decision. Some films stick in the mind for reasons beyond the cinematic, don’t they? In the 2003 comedy Bruce Almighty, Jim Carey plays the character of God and, along with more obviously useful powers, he has to respond to the prayers of the world. But people are always praying! He rapidly approaches a kind of madness as voices swim around him, clamouring for attention. He takes to reading the prayers in the form of e-mails. He tries to answer them individually but is receiving them faster than he can possibly respond. He decides to set his e-mail account to automatically answer “yes” to all, assuming that this will make everybody happy. Of course, it does not.

Some films stick in the mind for reasons beyond the cinematic, don’t they? In the 2003 comedy Bruce Almighty, Jim Carey plays the character of God and, along with more obviously useful powers, he has to respond to the prayers of the world. But people are always praying! He rapidly approaches a kind of madness as voices swim around him, clamouring for attention. He takes to reading the prayers in the form of e-mails. He tries to answer them individually but is receiving them faster than he can possibly respond. He decides to set his e-mail account to automatically answer “yes” to all, assuming that this will make everybody happy. Of course, it does not.

Perhaps one explanation of why the question ‘what is poetry?’ is so difficult to answer is because it is, to a large extent, an art of the negative, of avoidance.

Perhaps one explanation of why the question ‘what is poetry?’ is so difficult to answer is because it is, to a large extent, an art of the negative, of avoidance.

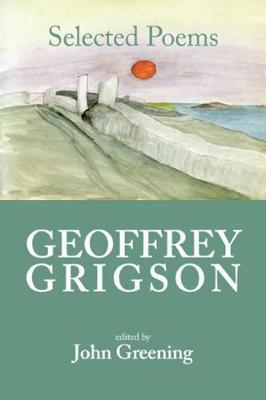

*As a labouring translator myself, I have long remembered Grigson’s brilliant put-down in his Introduction to the Faber Book of Love Poems (1973). Explaining why he has not included any translations at all, he declares that their “unmeasured, thin-rolled short crust” would prove detrimental to the health of the nation’s poetic taste. Times have changed, thank goodness.

*As a labouring translator myself, I have long remembered Grigson’s brilliant put-down in his Introduction to the Faber Book of Love Poems (1973). Explaining why he has not included any translations at all, he declares that their “unmeasured, thin-rolled short crust” would prove detrimental to the health of the nation’s poetic taste. Times have changed, thank goodness.