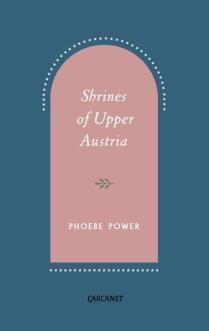

As in the previous four years, I am posting – over the summer – my reviews of the 5 collections chosen for the Forward Prizes Felix Dennis award for best First Collection. This year’s £5000 prize will be decided on Sunday 20th October 2019. Click on this link to access all 5 of my reviews of the 2018 shortlisted books (eventual winner Phoebe Power), here for my reviews of the 2017 shortlisted books (eventual winner Ocean Vuong), here for my reviews of the 2016 shortlisted books (eventual winner Tiphanie Yanique), here for my reviews of the 2015 shortlisted books (eventual winner Mona Arshi).

The full 2019 shortlist is:

Raymond Antrobus – The Perseverance (Penned in the Margins)

Jay Bernard – Surge (Chatto & Windus)

David Cain – Truth Street (Smokestack Books) – reviewed here.

Isabel Galleymore – Significant Other (Carcanet) – reviewed here.

Stephen Sexton – If All the World and Love Were Young (Penguin Books)

Raymond Antrobus’ The Perseverance has already received a great deal of coverage since being chosen as a Poetry Book Society Choice in September 2018. It is a collection that has achieved the difficult task of transcending the acclamation of the poetry world to a much more widespread appreciation, such as winning the Rathbone’s Folio Prize 2019 (awarded to “the best work of literature of the year, regardless of form”). In many ways it is a conventional book of poems – its voice is colloquial, it successfully employs a range of (now) traditional forms (dramatic monologues, prose poem, sestina, ghazal, pantoum), its forms, syntax and punctuation are nothing out of the ordinary (compared to the work of Danez Smith, for example, a comparison that Antrobus invites). Its subject matter is to a large extent dominated by a son’s relationship with his father, by questions of racial identity and (this is what is especially distinctive) the experience of a young Deaf man. Besides the latter, what really marks the book out as special is that impossible-to-teach, impossible-to-fake, not especially ultra-modern quality of compassion.

I think the portrait of the “complicated man”, Raymond Antrobus’ father, is remarkable. This is a warts and all portrayal as can be seen in the title poem, a sestina, in which the boy’s seemingly endless and repeated waiting for his father to come out of the pub called ‘The Perseverance’ is reflected in the repetitions of the poetic form. The neglect of the child (and of the mother of his child) is made perfectly clear; one of the repeating rhyme words is ‘disappear’. But another is ‘perseverance’ itself which sets up sweetly ironic resonances in relation to the experiences of both father and child. But a third rhyme word is ‘laughter’ which transmutes in significance as the poem develops. At first it is the distant din from the inside of the pub. It grows into a sort of paternal life-view: “There is no such thing as too much laughter”. In the end, after the loss of the father, it is what the son remembers, rather than the neglect: “I am still outside THE PERSEVERANCE, listening for the laughter”.

Antrobus’ epigraph to ‘The Perseverance’ quotes from ‘Where you gonna run’, a lyric by Peter Tosh: “Love is the man overstanding”. The latter word means a form of understanding that emerges after all untruths have been overcome. The poems scattered through this collection make it clear that a full overstanding of his “complicated” father took a while. The disciplining of his child often took the form of “a fist”. When Raymond knocked loose wires from his father’s sound system, the response was a beating. Yet, “every birthday he bought me / a dictionary”. His father could recite “Wordsworth and Coleridge”. He never called his son deaf, but rather “limited”, and he would read with him in the evenings (more of that later). But then he might regale his son with tales of his extensive sexual experiences, “three children with three different women”. In the end, as so often, the child ends nursing the infantilised father who is suffering from dementia. The father’s mind is filled with the past, his own growing up in Jamaica, his first kiss, his later, difficult life in England. ‘Dementia’ deploys a second person address to the condition itself:

you simplified a complicated man,

swallowed his past

until your breath was

warm as Caribbean

concrete —

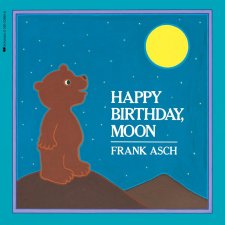

In the final poem in the book, Antrobus again uses a traditional form – a pantoum this time – to evoke some of the moments of closeness between father and son as they read together. In ‘Happy Birthday Moon’ the father’s attentive, gentle, encouraging side is memorialised as is the Deaf child’s desire to please his father:

Dad makes the Moon say something new every night

and we hear each other, really hear each other.

As Dad reads aloud, I follow his finger across the page.

Much earlier in the book, Antrobus writes of clearing his father’s flat after his death. On an old cassette tape, stowed away for years, the poet now listens to a recording of his own two-year-old voice, repeating his surname: “Antrob, Antrob, Antrob”. The final syllable is missing because the child could not hear it. At the time of the recording, no-one in the family suspected there was an issue. Years later, Antrobus sits “listening to the space of deafness”. Other sections of this early sequence, ‘Echo’, document the Deaf child’s experiences of slow diagnosis (“since deafness / did not run in the family”) and the tests that finally revealed the truth. These are important poems for the hearing world to read; the lazy inaccuracies and limitations of our imaginations always need re-invigorating with the truth of lived experience. The first section of ‘Echo’ takes us straight into the experience of “ear amps”, of “misty hearing aid tubes”, of doorbells that do not ring but pulsate with light.

Antrobus’ subject is only partly the frustrations of Deafness (capital D refers to those who are born Deaf – hence a state of identity, a cultural difference – as opposed to small d which refers to those who become deaf, having acquired spoken language, whose relationship with deafness is more as disability, as medical condition). One poem uses the repeated refrain “What?” Another, with courageous humour, records every day mis-hearings such as muddling “do you want a pancake” with “you look melancholic”. But it is more often the capability of the d/Deaf that Antrobus wants to proclaim: whether the doorbell is heard or seen, “I am able to answer”.

Inevitably, there is anger to be expressed. We feel the heat of this especially in ‘Dear Hearing World’ which, as Antrobus’ note confirms, contains “riffs and remixes of lines” from ‘dear white america’, a poem by Danez Smith included in Don’t Call Us Dead (Chatto, 2017). Smith’s example – a prose poem full of frustrated anger and a desperate wishfulness for better race relations in the USA – seems to liberate Antrobus’ voice. He wishes – or rather demands – better treatment for the d/Deaf: “I want . . . I want . . . I call you out. . . I am sick of. . .” The hearing world is castigated for its mistreatment of the d/Deaf: “You taught me I was inferior to standard English expression – / I was a broken speaker, you were never a broken interpreter”. Antrobus also takes aim at some high profile figures for their attitudes to d/Deafness. I remember being asked (and refusing) to teach Ted Hughes’ poem ‘Deaf School’ (collected in Moortown (Faber, 1979)). Antrobus here reprints and redacts the whole poem, following it with an excoriating commentary on Hughes’ patronising and presumptuous comments. Elsewhere Charles Dickens and Alexander Graham Bell come in for criticism.

Inevitably, there is anger to be expressed. We feel the heat of this especially in ‘Dear Hearing World’ which, as Antrobus’ note confirms, contains “riffs and remixes of lines” from ‘dear white america’, a poem by Danez Smith included in Don’t Call Us Dead (Chatto, 2017). Smith’s example – a prose poem full of frustrated anger and a desperate wishfulness for better race relations in the USA – seems to liberate Antrobus’ voice. He wishes – or rather demands – better treatment for the d/Deaf: “I want . . . I want . . . I call you out. . . I am sick of. . .” The hearing world is castigated for its mistreatment of the d/Deaf: “You taught me I was inferior to standard English expression – / I was a broken speaker, you were never a broken interpreter”. Antrobus also takes aim at some high profile figures for their attitudes to d/Deafness. I remember being asked (and refusing) to teach Ted Hughes’ poem ‘Deaf School’ (collected in Moortown (Faber, 1979)). Antrobus here reprints and redacts the whole poem, following it with an excoriating commentary on Hughes’ patronising and presumptuous comments. Elsewhere Charles Dickens and Alexander Graham Bell come in for criticism.

Of course, such blinkered prejudices about d/Deafness and race remain rife as ‘Miami Airport’, a fragmented account of an interrogation at the US border, makes clear. With Palestinian poet, Mahmoud Darwish, the British-Jamaican poet, Antrobus, would say, “I am from there, I am from here”. Born to an English mother, his father always tried to keep his Jamaican heritage alive. But even his appearance speaks two stories as in ‘Ode to my Hair’: “do you rise like wild wheat / or a dark field of frightened strings?” And the subtly shifting meanings of repetition in the ghazal form of ‘Jamaican British’ cleverly brings out the liminal spaces imposed on individuals who share Antrobus’ ancestry.

But despite the many issues raised in this book, it is not in the end to be praised for its campaigning zeal. In the wonderfully titled ‘After Being Called a Fucking Foreigner in London Fields’, Antrobus confesses, “I’m all heart, / no technique”. He’s talking about fist fights here, but it’s certainly not true of his poetry. There is plenty of technique and skill on show, but it is put to the service of the “heart”. Not in a sentimental way at all – these poems can tell brutal truths – but in the compassion, the love, that most of the poems exude. There are plenty of essays and definitions of identity around these days and there is rightfully plenty of blame-work, but Antrobus finds it in himself to forgive. Instead of punching his abuser in London Fields, he “write[s] until everything goes / quiet” and in ‘Closure’, addressing someone who knifed him years ago, he finds the strength to say, “There is no knife I want to open you with. Keep all your blood”. This is a first collection that barely puts a foot wrong and thoroughly deserves the praise that has already been heaped upon it.

But despite the many issues raised in this book, it is not in the end to be praised for its campaigning zeal. In the wonderfully titled ‘After Being Called a Fucking Foreigner in London Fields’, Antrobus confesses, “I’m all heart, / no technique”. He’s talking about fist fights here, but it’s certainly not true of his poetry. There is plenty of technique and skill on show, but it is put to the service of the “heart”. Not in a sentimental way at all – these poems can tell brutal truths – but in the compassion, the love, that most of the poems exude. There are plenty of essays and definitions of identity around these days and there is rightfully plenty of blame-work, but Antrobus finds it in himself to forgive. Instead of punching his abuser in London Fields, he “write[s] until everything goes / quiet” and in ‘Closure’, addressing someone who knifed him years ago, he finds the strength to say, “There is no knife I want to open you with. Keep all your blood”. This is a first collection that barely puts a foot wrong and thoroughly deserves the praise that has already been heaped upon it.

Michael Rosen talks to Raymond Antrobus on BBC Radio 4

But Galleymore also sees dangers. In her 2014

But Galleymore also sees dangers. In her 2014

Cain also cites the work of Charles Reznikioff and Svetlana Alexievich as models. The former, an Objectivist poet, developed work from

Cain also cites the work of Charles Reznikioff and Svetlana Alexievich as models. The former, an Objectivist poet, developed work from

In fact – as Cain’s sequence shows – what was being covered up was the original decision of Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield to open the exit gates at 2.47pm. One of his officers spoke to the inquiry: “I was quite shocked // It was totally unprecedented. // It was something you just didn’t do”. This was what caused the inflow of fans – “like sand into an egg timer”. Only at the second inquiry, did Duckenfield revise his earlier false statements: “I didn’t say, // ‘I have authorised the opening of the gates’”.

In fact – as Cain’s sequence shows – what was being covered up was the original decision of Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield to open the exit gates at 2.47pm. One of his officers spoke to the inquiry: “I was quite shocked // It was totally unprecedented. // It was something you just didn’t do”. This was what caused the inflow of fans – “like sand into an egg timer”. Only at the second inquiry, did Duckenfield revise his earlier false statements: “I didn’t say, // ‘I have authorised the opening of the gates’”.

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

You will have gathered that one of Power’s things is to mix English and Austrian German. This happens several times in ‘A Tour of Shrines of Upper Austria’ (though in this book we only get 7 parts of the full sequence). An observer stops at various shrine sites, jotting down some thoughts and taking a picture or two. Nothing is developed though Power’s poems do show an interest in religion on several other occasions. ‘The Moving Swan’ opens with a centre-justified prose description of candles flickering in a cathedral and another poem is drawn to the grave of two goats, observing: “two heaps of ivy/straw / one unlit red tealight”. And ‘Epiphany Night’ is a more extended series of notes recording a local celebration with bells, dressing-up, boats, lanterns. This is all observed in loosely irregular lines by the narrator from her “wohnung” (apartment). To wring all engagement or emotional or imaginative response from such a text is, I suppose, quite an achievement but to spend 70-odd pages in such company really is wearisome.

You will have gathered that one of Power’s things is to mix English and Austrian German. This happens several times in ‘A Tour of Shrines of Upper Austria’ (though in this book we only get 7 parts of the full sequence). An observer stops at various shrine sites, jotting down some thoughts and taking a picture or two. Nothing is developed though Power’s poems do show an interest in religion on several other occasions. ‘The Moving Swan’ opens with a centre-justified prose description of candles flickering in a cathedral and another poem is drawn to the grave of two goats, observing: “two heaps of ivy/straw / one unlit red tealight”. And ‘Epiphany Night’ is a more extended series of notes recording a local celebration with bells, dressing-up, boats, lanterns. This is all observed in loosely irregular lines by the narrator from her “wohnung” (apartment). To wring all engagement or emotional or imaginative response from such a text is, I suppose, quite an achievement but to spend 70-odd pages in such company really is wearisome.

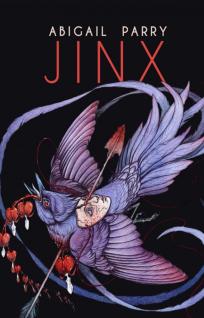

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”.

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”. For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?

For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?