In a recent launch reading for her second collection, Dear Big Gods (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019), Mona Arshi suggested it was a book she wrote only reluctantly. Her first book, Small Hands (2015), had at its centre a number of poems in memory of her brother, Deepak, who died unexpectedly in 2012. On her own admission, these new poems continue to be imbued with this grief and – though poets surely always write the book that needs to be written – there is a sense that the development of the new work has been stalled by such powerful feelings. My 2015 review of Small Hands saw Arshi as “an intriguing writer, potentially a unique voice if she can achieve the right distance between herself and her powerful formative influences”. The influences I had in mind then were literary rather than personal, but I find the lack of distance travelled between the earlier and this more recent work rather disappointing.

In a recent launch reading for her second collection, Dear Big Gods (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019), Mona Arshi suggested it was a book she wrote only reluctantly. Her first book, Small Hands (2015), had at its centre a number of poems in memory of her brother, Deepak, who died unexpectedly in 2012. On her own admission, these new poems continue to be imbued with this grief and – though poets surely always write the book that needs to be written – there is a sense that the development of the new work has been stalled by such powerful feelings. My 2015 review of Small Hands saw Arshi as “an intriguing writer, potentially a unique voice if she can achieve the right distance between herself and her powerful formative influences”. The influences I had in mind then were literary rather than personal, but I find the lack of distance travelled between the earlier and this more recent work rather disappointing.

In fact, Deepak’s death is the explicit subject on only a few occasions. The poem ‘When your Brother Steps into your Piccadilly, West Bound Train Carriage’ isn’t much longer than its own title but it evokes that familiar sense of (mis-)seeing our dead in a public place. The emotions remain raw, from the accusatory “how-the-fuck-could-you?” to the final “I am sorry, I’m so sorry”. A dream or daydream meeting is also the basis for ‘A Pear from the Afterlife’ in which the brother’s affectionate tone advises, “Sis, you gotta let go / of this idea of definitive knowledge”. ‘Five Year Update’ is by far the most extended of these reflections on the brother’s passing, written in very long raking lines (rotated 45 degrees to stretch vertically on the page). “I hope it’s fine to contact you”, it opens and goes on to recall the moment the news of his death was received (see also ‘Phone Call on a Train Journey’ from Small Hands), remembers their childhood together and the sister’s continuing life: “I’ve gone down one lump not two, I still don’t swim and yes I still can’t / take a photograph”.

As the blurb suggests, these poems are indeed “lyrical and exact exploration[s] of the aftershocks of grief”. But ‘Everywhere’ adopts a little more distance and develops the kind of floating and delicate lyricism that Arshi does so well. The absent brother/uncle is still alluded to: “We tell the children, we should not / look for him. He is everywhere”. As that final phrase suggests, the rawness of the grief is being transmuted into a sense of otherness, beyond the quotidian and material. It’s when Arshi takes her brother’s advice and lets go of “definitive knowledge” that her poems promise so much. ‘Little Prayer’ might be spoken by the dead or the living, left abandoned, but either way it argues a stoical resistance: “I am still here // hunkered down”. In a more conventional mode, ‘The Lilies’ develops the objective correlative of the flowers suffering from blight as an image of a spoliation that hurts and reminds, yet is allowed to persist: “I let them live on / beauty-drained / in their altar beds”.

As the blurb suggests, these poems are indeed “lyrical and exact exploration[s] of the aftershocks of grief”. But ‘Everywhere’ adopts a little more distance and develops the kind of floating and delicate lyricism that Arshi does so well. The absent brother/uncle is still alluded to: “We tell the children, we should not / look for him. He is everywhere”. As that final phrase suggests, the rawness of the grief is being transmuted into a sense of otherness, beyond the quotidian and material. It’s when Arshi takes her brother’s advice and lets go of “definitive knowledge” that her poems promise so much. ‘Little Prayer’ might be spoken by the dead or the living, left abandoned, but either way it argues a stoical resistance: “I am still here // hunkered down”. In a more conventional mode, ‘The Lilies’ develops the objective correlative of the flowers suffering from blight as an image of a spoliation that hurts and reminds, yet is allowed to persist: “I let them live on / beauty-drained / in their altar beds”.

Like so many first books, Small Hands experimented with various poetical forms. This book also – a bit wilfully – tries out tanka, poems in two columns, right justification, centre justification, ghazals, inter-cut texts, prose poems, a sestina, an Emily Dickinson parody and responses to Lorca and The Mahabharata. They don’t all work equally well and Arshi perhaps senses this in lines like these:

My little bastard verses

tiny polyglot faces

how light you are

how virtually weightless

The irony may be that this sort of form and reach actually does show Arshi at her best. The sequence of tiny poems modelled on Lorca’s ‘Mirror Suite’ (1921-1923) is fascinating. Jerome Rothenburg, discussing Lorca’s poems, describes them as possessing “a coolness & (sometimes) quirkiness, a playfulness of mind & music that I found instantly attractive”. These same qualities – as with Lorca, a version of surrealism, a firm but gentle turning aside from “definitive knowledge” – I enjoy in Arshi’s work as she explores states of the heart and realms of knowledge not ordinarily encountered or encompassed. Dear Big Gods contains other such Lorca-esque sequences such as ‘Autumn Epistles’, ‘Grief Holds a Cup of Tea’ and ‘Let the Parts of the Flower Speak’ and these are far more interesting than the poems drawn from The Mahabharata or the experiments in prose.

Arshi’s continuing love affair with ghazals also seems to me to be an aspect of this same search for a form that holds both the connected and the stand-alone in a creative tension. ‘Ghazal: Darkness’ is very successful with the second line of each couplet returning to the refrain word, “darkness”, while the connective tissue of the poem allows a roaming through woods, soil, mushrooms and a mother’s praise of her daughters. Poems based on – or at least with the qualities of – dreams also stand out. The doctor in ‘Delivery Room’ asks the mother in the midst of her contractions, “Do you prefer the geometric or lyrical approach?” In ‘The Sisters’ the narrator dreams of “all the sisters I never had” and within 10 lines Arshi has expressed complex yearnings about loneliness and protectiveness in relation to siblings and self.

Arshi’s continuing love affair with ghazals also seems to me to be an aspect of this same search for a form that holds both the connected and the stand-alone in a creative tension. ‘Ghazal: Darkness’ is very successful with the second line of each couplet returning to the refrain word, “darkness”, while the connective tissue of the poem allows a roaming through woods, soil, mushrooms and a mother’s praise of her daughters. Poems based on – or at least with the qualities of – dreams also stand out. The doctor in ‘Delivery Room’ asks the mother in the midst of her contractions, “Do you prefer the geometric or lyrical approach?” In ‘The Sisters’ the narrator dreams of “all the sisters I never had” and within 10 lines Arshi has expressed complex yearnings about loneliness and protectiveness in relation to siblings and self.

Given the traumatic disruption of her own, it’s no surprise that Arshi’s most frequently visited subject area is family relationships. I’ve referred to several of these poems already and ‘Gloaming’ floats freely through the fears of losing a child, the care of an ageing father, a mother “entering/leaving through a narrow lintel” and the recall of the “thick soup of our childhood”. The soup works well both as literal food stuff and as metaphor for the nourishing, warming milieu of an up-bringing, though the girl who looks up at the end of the poem is already exploring questions of identity. She asks, “where are you from, what country are we in?” Given Arshi’s own background – born to Punjabi Sikh parents in West London – such questions have obvious autobiographical and political relevance, though I sense Arshi herself is also asking questions of a more spiritual nature.

So, in ‘My Third Eye’, the narrator is “more perplexed than annoyed” that her own third eye – the mystical and esoteric belief in a speculative, spiritual perception – has not yet “opened”. The poem’s mode and tone is comic for the most part; there is a childish impatience in the voice, asking “Am I not as worthy as the buffalo, the ferryman, / the cook and the Dalit?”. But in the final lines, the holy man she visits is given more gravitas. He touches the narrator’s head “and with that my eyes suddenly watered, widened and / he sent me on my way as I was forever open open open”. The book also closes with the title poem, ‘Dear Big Gods’, which takes the form of a prayer: “all you have to do / is show yourself”, it pleads. The delicate probing of Arshi’s best poems, their stretching of perception and openness to unusual states of emotion are driven by this sort of spiritual quest. Personal tragedy has no doubt fed this creative drive but – as the poet seems to be aware – such grief is only an aspect of her vision and not the whole of it.

So, in ‘My Third Eye’, the narrator is “more perplexed than annoyed” that her own third eye – the mystical and esoteric belief in a speculative, spiritual perception – has not yet “opened”. The poem’s mode and tone is comic for the most part; there is a childish impatience in the voice, asking “Am I not as worthy as the buffalo, the ferryman, / the cook and the Dalit?”. But in the final lines, the holy man she visits is given more gravitas. He touches the narrator’s head “and with that my eyes suddenly watered, widened and / he sent me on my way as I was forever open open open”. The book also closes with the title poem, ‘Dear Big Gods’, which takes the form of a prayer: “all you have to do / is show yourself”, it pleads. The delicate probing of Arshi’s best poems, their stretching of perception and openness to unusual states of emotion are driven by this sort of spiritual quest. Personal tragedy has no doubt fed this creative drive but – as the poet seems to be aware – such grief is only an aspect of her vision and not the whole of it.

Lieke Marsman’s The Following Scan Will Last Five Minutes (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019) is an unlikely little gem of a book about cancer, language, poetry, Dutch politics, philosophy, the environment, the art of translation and friendship – all bound together by a burning desire (in both original author and her translator, Sophie Collins) to advocate the virtues of empathy. The PBS have chosen it as their Summer 2019 Recommended Translation.

Lieke Marsman’s The Following Scan Will Last Five Minutes (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019) is an unlikely little gem of a book about cancer, language, poetry, Dutch politics, philosophy, the environment, the art of translation and friendship – all bound together by a burning desire (in both original author and her translator, Sophie Collins) to advocate the virtues of empathy. The PBS have chosen it as their Summer 2019 Recommended Translation. The sort of silence Lorde fears is evoked in the monitory opening poem. Its unusual, impersonal narration is acutely aware of the lure of sinking away into the “morphinesweet unreality of the everyday”, of the allure of self-imposed isolation (“unplugg[ing] your router”) in the face of the diagnosis of disease. What the voice advises is the recognition that freedom consists not in denial, in being free of pain or need, but in being able to recognise our needs and satisfy them: “to be able to get up and go outside”. It’s this continuing self-awareness and the drive to try to achieve it that Marsman hopes for and (happily) comes to embody. But it was never going to be easy and towards the end of the poem sequence, these needs are honed to the bone:

The sort of silence Lorde fears is evoked in the monitory opening poem. Its unusual, impersonal narration is acutely aware of the lure of sinking away into the “morphinesweet unreality of the everyday”, of the allure of self-imposed isolation (“unplugg[ing] your router”) in the face of the diagnosis of disease. What the voice advises is the recognition that freedom consists not in denial, in being free of pain or need, but in being able to recognise our needs and satisfy them: “to be able to get up and go outside”. It’s this continuing self-awareness and the drive to try to achieve it that Marsman hopes for and (happily) comes to embody. But it was never going to be easy and towards the end of the poem sequence, these needs are honed to the bone:

Marsman tells us she read Audre Lorde and Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor after her operation and discharge from hospital. It’s Sontag who draws attention to the role of language in the way patients themselves and other people respond to cancer. Marsman asks herself: “Am I experiencing this cancer as an Actual Hell [. . .] or because that is the common perception of cancer?” The implied failure to achieve truly empathetic perception of the role and nature of the disease is echoed horribly in the empathetic failures and hypocrisies of Dutch politicians (UK readers will find this stuff all too familiar in our own politics). Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, blithely allocates billions of euros to multinationals like Shell and Unilever (on no valid basis) while overseeing cuts in health services. Marsman reads this as a failure to empathise with the ill. Another politician, Klaas Dijkhoff, reduces benefits on the basis that people encountering “bad luck” need to get themselves back on their own two feet. Bad luck here includes illness, disability, being born into poverty or abusive families, being compelled to flee your own country. Marsman’s own encounter with such ‘bad luck’ makes her rage all the more incandescent.

Marsman tells us she read Audre Lorde and Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor after her operation and discharge from hospital. It’s Sontag who draws attention to the role of language in the way patients themselves and other people respond to cancer. Marsman asks herself: “Am I experiencing this cancer as an Actual Hell [. . .] or because that is the common perception of cancer?” The implied failure to achieve truly empathetic perception of the role and nature of the disease is echoed horribly in the empathetic failures and hypocrisies of Dutch politicians (UK readers will find this stuff all too familiar in our own politics). Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, blithely allocates billions of euros to multinationals like Shell and Unilever (on no valid basis) while overseeing cuts in health services. Marsman reads this as a failure to empathise with the ill. Another politician, Klaas Dijkhoff, reduces benefits on the basis that people encountering “bad luck” need to get themselves back on their own two feet. Bad luck here includes illness, disability, being born into poverty or abusive families, being compelled to flee your own country. Marsman’s own encounter with such ‘bad luck’ makes her rage all the more incandescent.

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

In the summer of 2018, John Greening spent 2 weeks as artist-in-residence at the Heinrich Boll cottage in Dugort, Achill Island. The resulting

In the summer of 2018, John Greening spent 2 weeks as artist-in-residence at the Heinrich Boll cottage in Dugort, Achill Island. The resulting

One day around 1973/4, Ted Hughes bought or was given

One day around 1973/4, Ted Hughes bought or was given

Ted Hughes began by modelling poems of his own closely on the work of the poet that Ramanujan places first in the collection, the 12th century Indian poet-saint, Basavanna. Early on Hughes adheres closely to the originals but gradually he distances himself, starting to create more original poems, often employing personal materials, and (as I have said) some of these little poems eventually found their way into the final section of Gaudete. The refrain and invocation that Basavanna uses in the majority of his poems is the address to Siva as “lord of the meeting rivers”. The influence of Robert Graves’ The White Goddess is well known on Hughes and he decided to experiment with addressing his own conception of the divinity – a female divinity – at once his muse and the fundamental animating force in the world, as “Lady of the Hill”.

Ted Hughes began by modelling poems of his own closely on the work of the poet that Ramanujan places first in the collection, the 12th century Indian poet-saint, Basavanna. Early on Hughes adheres closely to the originals but gradually he distances himself, starting to create more original poems, often employing personal materials, and (as I have said) some of these little poems eventually found their way into the final section of Gaudete. The refrain and invocation that Basavanna uses in the majority of his poems is the address to Siva as “lord of the meeting rivers”. The influence of Robert Graves’ The White Goddess is well known on Hughes and he decided to experiment with addressing his own conception of the divinity – a female divinity – at once his muse and the fundamental animating force in the world, as “Lady of the Hill”. But as in the best poetry, such simplicity of language and tone belies the spiritual intentions of the originals and of Hughes’ experimental vacana poems too. As Ann Skea explains, in his turn, Hughes “becomes the spiritual bridegroom of the Lady of the Hill and struggles to be worthy of that union”. Unlike the original Indian poems, Hughes seems to see his Goddess in every human female and they are seen as testing and challenging the poet to further spiritual growth. In the end, just 18 of these experimental poems were chosen to form the Epilogue to Gaudete as the songs sung by the Reverend Nicholas Lumb on his return from the underworld: a man who had seen things and felt the need to communicate those things: “he saw the notebook again, lying on the table, and he remembered the otter and the strange way it had come up out of the lough because a man had whistled. He opened the notebook and began to decipher the words, he found a pen and clean paper and began to copy out the verses”.

But as in the best poetry, such simplicity of language and tone belies the spiritual intentions of the originals and of Hughes’ experimental vacana poems too. As Ann Skea explains, in his turn, Hughes “becomes the spiritual bridegroom of the Lady of the Hill and struggles to be worthy of that union”. Unlike the original Indian poems, Hughes seems to see his Goddess in every human female and they are seen as testing and challenging the poet to further spiritual growth. In the end, just 18 of these experimental poems were chosen to form the Epilogue to Gaudete as the songs sung by the Reverend Nicholas Lumb on his return from the underworld: a man who had seen things and felt the need to communicate those things: “he saw the notebook again, lying on the table, and he remembered the otter and the strange way it had come up out of the lough because a man had whistled. He opened the notebook and began to decipher the words, he found a pen and clean paper and began to copy out the verses”.

Did you know Hesiod probably pre-dates Homer? Hesiod is aware of the siege of Troy but he makes no reference to Homer’s Iliad. He’s usually placed before Homer in lists of the first poets. The other striking aspect of Works and Days is that (unlike Homer) he is not harking back to already lost eras and heroic actions. Hesiod talks about his own, contemporary workaday world, offering advice to his brother because they seem to be in a dispute with each other. Hesiod’ anti-heroic focus is an antidote to the Gods, the top brass and military heroes of Homer. Most of us live – and prefer to live – in Hesiod’s not Homer’s world.

Did you know Hesiod probably pre-dates Homer? Hesiod is aware of the siege of Troy but he makes no reference to Homer’s Iliad. He’s usually placed before Homer in lists of the first poets. The other striking aspect of Works and Days is that (unlike Homer) he is not harking back to already lost eras and heroic actions. Hesiod talks about his own, contemporary workaday world, offering advice to his brother because they seem to be in a dispute with each other. Hesiod’ anti-heroic focus is an antidote to the Gods, the top brass and military heroes of Homer. Most of us live – and prefer to live – in Hesiod’s not Homer’s world. He seems to have been a poet-farmer who makes sure we are aware that he has already won a literary competition at a funeral games on the island of Euboea. His prize-winning piece may well have been his earlier

He seems to have been a poet-farmer who makes sure we are aware that he has already won a literary competition at a funeral games on the island of Euboea. His prize-winning piece may well have been his earlier  There are further reasons to set to work in the very nature of the cosmos and the human world. Hesiod tells the Pandora story here. Zeus causes the creation of a female figure, Pandora, as a way of avenging Prometheus’ pro-humankind actions (stealing fire from the gods, for example). Her name suggests she is a concoction or committee-created figure from contributions from all the Olympian Gods. She is given a jar which she opens: “ere this the tribes of men lived on earth remote and free from ills and hard toil and heavy sickness [. . .] But the woman took off the great lid of the jar with her hands and scattered all these and her thought caused sorrow and mischief to men” (tr. Evelyn-White). Hesiod’s locating of the root of human sorrow in the actions of a woman echoes the Christian story of the loss of Paradise and it is one of the reasons why Hesiod has been accused of misogyny, though as Stallings suggests, he’s not any more complimentary about the males of the human race.

There are further reasons to set to work in the very nature of the cosmos and the human world. Hesiod tells the Pandora story here. Zeus causes the creation of a female figure, Pandora, as a way of avenging Prometheus’ pro-humankind actions (stealing fire from the gods, for example). Her name suggests she is a concoction or committee-created figure from contributions from all the Olympian Gods. She is given a jar which she opens: “ere this the tribes of men lived on earth remote and free from ills and hard toil and heavy sickness [. . .] But the woman took off the great lid of the jar with her hands and scattered all these and her thought caused sorrow and mischief to men” (tr. Evelyn-White). Hesiod’s locating of the root of human sorrow in the actions of a woman echoes the Christian story of the loss of Paradise and it is one of the reasons why Hesiod has been accused of misogyny, though as Stallings suggests, he’s not any more complimentary about the males of the human race. It’s certainly the lazy, self-serving, arrogant younger brother who forms the focus of the rest of the poem: “So Perses, you be heedful of what’s right . . . So Perses, mull these matters in your mind . . . Fool Perses, what I say’s for your own good” (tr. Stallings). It’s true that his name gradually fades from the text in the final 500 lines but the torrent of imperatives, offering advice and guidance on a range of practical issues, often sounds like haranguing from a concerned, perhaps slightly pissed off, brother. Much of this material is phenological – when to sow crops, when to harvest, when to shear your sheep. In winter, don’t hang around the blacksmith’s forge where other wasters gather to chat and pass the time. It’s safe to put to sea when the new fig leaves are the size of crow’s feet.

It’s certainly the lazy, self-serving, arrogant younger brother who forms the focus of the rest of the poem: “So Perses, you be heedful of what’s right . . . So Perses, mull these matters in your mind . . . Fool Perses, what I say’s for your own good” (tr. Stallings). It’s true that his name gradually fades from the text in the final 500 lines but the torrent of imperatives, offering advice and guidance on a range of practical issues, often sounds like haranguing from a concerned, perhaps slightly pissed off, brother. Much of this material is phenological – when to sow crops, when to harvest, when to shear your sheep. In winter, don’t hang around the blacksmith’s forge where other wasters gather to chat and pass the time. It’s safe to put to sea when the new fig leaves are the size of crow’s feet. These are the passages that, around 29BC, inspired Virgil to his own farmer’s manual, the Georgics. Hesiod ends his poem in a rather perfunctory manner, roughly saying he who follows this good advice will become “blessed and rich”. But given Pandora’s jar and the Iron Age we live in, even this seems a mite optimistic. And of course, Perses never gets the chance to speak for himself. But I guess the tensions between his brother’s call for social and religious conformity and Perses’ individualistic disobedience to the demands of the gods and the sense of what is best for a society have gone on to form the basis of the continuing Western literary canon. And does any of this help with Brexit? I conclude (largely with Hesiod) the bleeding obvious: it’s complicated – solutions must be negotiated, don’t hope for some golden age because in a fallen, less-than-ideal, complex society it’s better for the future to be decided in the glacier-slow committee rooms of a plurality of voices than in the stark divisions and dramas of the battlefield. Work hard – have patience – don’t buy into fairy tales of a recoverable golden age.

These are the passages that, around 29BC, inspired Virgil to his own farmer’s manual, the Georgics. Hesiod ends his poem in a rather perfunctory manner, roughly saying he who follows this good advice will become “blessed and rich”. But given Pandora’s jar and the Iron Age we live in, even this seems a mite optimistic. And of course, Perses never gets the chance to speak for himself. But I guess the tensions between his brother’s call for social and religious conformity and Perses’ individualistic disobedience to the demands of the gods and the sense of what is best for a society have gone on to form the basis of the continuing Western literary canon. And does any of this help with Brexit? I conclude (largely with Hesiod) the bleeding obvious: it’s complicated – solutions must be negotiated, don’t hope for some golden age because in a fallen, less-than-ideal, complex society it’s better for the future to be decided in the glacier-slow committee rooms of a plurality of voices than in the stark divisions and dramas of the battlefield. Work hard – have patience – don’t buy into fairy tales of a recoverable golden age.

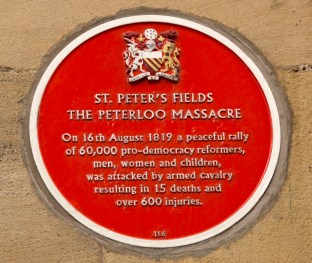

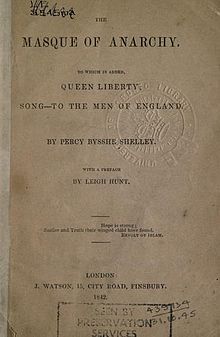

Earth continues by diagnosing the state of slavery into which England has fallen. This – and the following passage with its more positive analysis of what Freedom means to working people – makes for powerful, relevant, realistic reading in contrast to Shelley’s hard-to-pin-down mechanisms of political change. Slavery is to have to work and be paid only enough to live for another day’s work. It is to work not for oneself but for “tyrants”. It is to see family suffering and dying, to go hungry while the rich man surfeits his dogs. It is to suffer the “forgery” of paper money, to have no control over one’s own destiny. It is – when driven to the point of protest – a more direct reference to events in Manchester – “to see the Tyrant’s crew / Ride over your wives and you”.

Earth continues by diagnosing the state of slavery into which England has fallen. This – and the following passage with its more positive analysis of what Freedom means to working people – makes for powerful, relevant, realistic reading in contrast to Shelley’s hard-to-pin-down mechanisms of political change. Slavery is to have to work and be paid only enough to live for another day’s work. It is to work not for oneself but for “tyrants”. It is to see family suffering and dying, to go hungry while the rich man surfeits his dogs. It is to suffer the “forgery” of paper money, to have no control over one’s own destiny. It is – when driven to the point of protest – a more direct reference to events in Manchester – “to see the Tyrant’s crew / Ride over your wives and you”.

The third reason Shelley gives – via the voice of the earth – also offers only equivocal, indeed very uncomfortable, hope. Offering little or no consolation to the victims and their relations – though a point proven true through many centuries – such massacres by repressive forces will prove an inspiration to those who come after them: “that slaughter to the Nation / Shall steam up like inspiration”. Using another of his images for revolutionary fervour, this steam will eventually result in a volcanic explosion, “heard afar”. Once more in this poem, these reverberations are translated into words to mark “Oppression’s thundered doom”, stirring the people in their on-going fight for justice and liberty. Shelley concludes with the actual words he imagines being uttered – and we have heard them before:

The third reason Shelley gives – via the voice of the earth – also offers only equivocal, indeed very uncomfortable, hope. Offering little or no consolation to the victims and their relations – though a point proven true through many centuries – such massacres by repressive forces will prove an inspiration to those who come after them: “that slaughter to the Nation / Shall steam up like inspiration”. Using another of his images for revolutionary fervour, this steam will eventually result in a volcanic explosion, “heard afar”. Once more in this poem, these reverberations are translated into words to mark “Oppression’s thundered doom”, stirring the people in their on-going fight for justice and liberty. Shelley concludes with the actual words he imagines being uttered – and we have heard them before:

But as Shelley’s sentence crosses the next stanza break – ie. without any clear pause – the seemingly unstoppable parade of bloodshed, inequality, injustice and hypocrisy is strangely interrupted by a counter personification. A crazed-looking young woman (“a maniac maid”) runs out declaring that her name is Hope, though the narrator says “she looked more like Despair”. The perception here is interesting as even Shelley’s narrator has been so infected by the toxic atmosphere spread by Anarchy that the girl (who is soon to bring about a challenge to Anarchy) looks to be insane and more resembles the absence of hope than otherwise. This is one of Shelley’s core political beliefs and had already appeared in the closing lines of Prometheus Unbound. There, Demogorgon urges optimism in the long term conflict with abusive power: “to hope, till Hope creates / From its own wreck the thing it contemplates”. The movement for Reform will – it seems – have to come close to despair, or its own wreck, before the powers of Anarchy are likely to be defeated.

But as Shelley’s sentence crosses the next stanza break – ie. without any clear pause – the seemingly unstoppable parade of bloodshed, inequality, injustice and hypocrisy is strangely interrupted by a counter personification. A crazed-looking young woman (“a maniac maid”) runs out declaring that her name is Hope, though the narrator says “she looked more like Despair”. The perception here is interesting as even Shelley’s narrator has been so infected by the toxic atmosphere spread by Anarchy that the girl (who is soon to bring about a challenge to Anarchy) looks to be insane and more resembles the absence of hope than otherwise. This is one of Shelley’s core political beliefs and had already appeared in the closing lines of Prometheus Unbound. There, Demogorgon urges optimism in the long term conflict with abusive power: “to hope, till Hope creates / From its own wreck the thing it contemplates”. The movement for Reform will – it seems – have to come close to despair, or its own wreck, before the powers of Anarchy are likely to be defeated. This mist – later called a “Shape” – is one of the mysteries of the poem’s politics. Hope provokes its appearance. At first weak, it gathers in strength. Shelley compares it to clouds that gather “Like tower-crowned giants striding fast, / And glare with lightnings as they fly, /And speak in thunder to the sky”. In the next few stanzas it becomes more soldierly, “arrayed in mail”, compared to the scales of a snake (for Shelley the snake was usually an image of just rebellion not of evil), yet it is also winged. It wears a helmet with the image of the planet Venus on it. It moves softly and swiftly – a sensed but almost unseen presence. And rather than any military action or campaign of civil disobedience, this Shape, conjured by Hope, creates thinking:

This mist – later called a “Shape” – is one of the mysteries of the poem’s politics. Hope provokes its appearance. At first weak, it gathers in strength. Shelley compares it to clouds that gather “Like tower-crowned giants striding fast, / And glare with lightnings as they fly, /And speak in thunder to the sky”. In the next few stanzas it becomes more soldierly, “arrayed in mail”, compared to the scales of a snake (for Shelley the snake was usually an image of just rebellion not of evil), yet it is also winged. It wears a helmet with the image of the planet Venus on it. It moves softly and swiftly – a sensed but almost unseen presence. And rather than any military action or campaign of civil disobedience, this Shape, conjured by Hope, creates thinking: Yet in the calm aftermath of these events, there comes a sense of renovation, a “sense awakening and yet tender / Was heard and felt” and, most importantly, there are further words. This time the speaker is unclear though it is “As if” the earth itself, the mother of English men and women, feeling such bloodshed on her brow, translates this spilt blood into a powerful, irresistible language, “an accent unwithstood”. Shelley repeats “As if” once more, confirming the mystery of this voice, a voice which proceeds now to speak the whole of the remainder of the poem. For Shelley, Poetry in his broad sense is “vitally metaphorical” and the earth’s imagined speeches convey a sense that the cause of liberty is in accordance with the truly understood (surely Rousseauistic) nature of creation.

Yet in the calm aftermath of these events, there comes a sense of renovation, a “sense awakening and yet tender / Was heard and felt” and, most importantly, there are further words. This time the speaker is unclear though it is “As if” the earth itself, the mother of English men and women, feeling such bloodshed on her brow, translates this spilt blood into a powerful, irresistible language, “an accent unwithstood”. Shelley repeats “As if” once more, confirming the mystery of this voice, a voice which proceeds now to speak the whole of the remainder of the poem. For Shelley, Poetry in his broad sense is “vitally metaphorical” and the earth’s imagined speeches convey a sense that the cause of liberty is in accordance with the truly understood (surely Rousseauistic) nature of creation.

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).