NB This review first appeared in a shortened form on the Agenda Magazine website.

Rilke in Paris, Rainer Maria Rilke & Maurice Betz, tr. Will Stone (French original 1941; Pushkin Press, 2019).

The argument of Maurice Betz’s memoir on Rilke’s various residencies in Paris between 1902 and 1914 is that the young poet’s experience of the French capital is what turned him into a great poet. Betz worked closely with Rilke on French translations of his work (particularly his novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (1910)). Will Stone’s excellent translation of Betz’s 1941 book, Rilke a Paris, elegantly encompasses its wide range of tones from biographical precision, to gossipy excitement and critical analysis. The book particularly focuses on Rilke’s struggle over a period of eight years to complete the novel which is autobiographical in so many ways, as Betz puts it “in effect a transcription of his own private journal or of certain letters”.

The argument of Maurice Betz’s memoir on Rilke’s various residencies in Paris between 1902 and 1914 is that the young poet’s experience of the French capital is what turned him into a great poet. Betz worked closely with Rilke on French translations of his work (particularly his novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (1910)). Will Stone’s excellent translation of Betz’s 1941 book, Rilke a Paris, elegantly encompasses its wide range of tones from biographical precision, to gossipy excitement and critical analysis. The book particularly focuses on Rilke’s struggle over a period of eight years to complete the novel which is autobiographical in so many ways, as Betz puts it “in effect a transcription of his own private journal or of certain letters”.

Rilke first arrived in Paris from Worpswede in northern Germany, a community of artists where he had met and married Clara Westhoff. But never one to truly reconcile himself either to community or intimacy, he had already left his wife to travel to Paris. Yet the anonymity, bustling energy and inequalities of the French capital appalled him. In letters to his wife and many others, it became clear that, as Stone’s Introduction argues, Paris had “unceremoniously torn Rilke out of his safe, somewhat fey nineteenth-century draped musings”. In ways reminiscent of Keats’ observations about feeling himself extinguished on entering a room full of people, Rilke would later recall how the city’s “grandeur, its near infinity” would annihilate his own sense of himself. Living at No.11, Rue Touillier, these initial impressions form the opening pages of The Notebooks.

But there were also more positive Parisian experiences, particularly in his meetings with Rodin who he was soon addressing as his “most revered master”. Famously, Rodin advised the young poet, “You must work. You must have patience. Look neither right nor left. Lead your whole life in this cycle and look for nothing beyond this life”. In terms of his patience and willingness to play such a long game, not only with his novel but also with the slow completion of Duino Elegies (1922), Rilke clearly took on this advice. Interestingly, Betz characterises Rilke’s methods of working on the novel, creating letters, notes, journal pages over a number of years, as “like sketches, studies of hands or torsos which the sculptor uses to prefigure a group work”.

But there were also more positive Parisian experiences, particularly in his meetings with Rodin who he was soon addressing as his “most revered master”. Famously, Rodin advised the young poet, “You must work. You must have patience. Look neither right nor left. Lead your whole life in this cycle and look for nothing beyond this life”. In terms of his patience and willingness to play such a long game, not only with his novel but also with the slow completion of Duino Elegies (1922), Rilke clearly took on this advice. Interestingly, Betz characterises Rilke’s methods of working on the novel, creating letters, notes, journal pages over a number of years, as “like sketches, studies of hands or torsos which the sculptor uses to prefigure a group work”.

Rilke was even employed briefly by Rodin as “a sort of private secretary”. Betz suggests Rilke simply offered to help out for a couple of hours a day with the famous sculptor’s correspondence. But this quickly expanded to fill the whole day and Rilke was soon confessing to Karl von der Heydt that “I must get back to a time for myself where I can be alone with my experience”. A break was inevitable though in later visits to Paris the two artists patched up any quarrel. In terms of his location during this period, Rilke had moved on to the Hotel Biron at 77 Rue de Varenne on the recommendation of Clara. Rilke in turn suggested it as a suitable studio base for Rodin who also settled there and over a number of years gradually took over more and more of the rooms. It is this building that, in 1919, was converted to the now much-visited Musee Rodin.

Betz suggests that the traumatic impact of Paris was the making of Rilke as an artist. Between 1899 and 1903, Rilke had been working on The Book of Hours, representing a “religious and mystical phase”. In contrast, Paris presented the poet with an often brutal but also more “human landscape”. He also discovered this was reflected in the French capital’s painters and poets. Baudelaire in particular was important. In personal letters (as well as in his finished novel) Rilke identifies the poem ‘Une Charogne’ (‘A Carcass’) as critical in “the whole development of ‘objective’ language, such as we now think to see in the works of Cezanne”. Baudelaire’s portrayal of a rotting body seems to have taught Rilke that “the creator has no more right to turn away from any existence [. . .] if he refuses life in a certain object, he loses in one blow a state of grace”.

But it took Rilke a while to arrive at this sort of inclusivity of vision. One of his earliest impressions of the city was that there were invalids, broken human bodies everywhere. “You see them appear at the windows of the Hotel-Dieu in their strange attire, the pale and mournful uniform of the invalid. You suddenly sense that in this vast city there are legions of the sick, armies of the dying, whole populations of the dead”. As Betz points out, this is one of the important observations made by the hero of The Notebooks. It is the “multiform face of death” that Brigge (and Rilke) confronts in Paris. And the irony is not lost on either of them because Paris, of course, at this time was renowned for its social and cultural vitality. Here, Rilke is being forced to make critical distinctions which he then worked on for the rest of his life: “Vital impulse, is that life then? No. Life is calm, immense, elemental. The craving to live is haste, pursuit. There is an impatience to possess life in its entirety, straight away. Paris is bloated with this desire and that’s why it is so close to death”. Years later, near the end of the fifth of the Duino Elegies, Rilke expresses something very similar (tr. Crucefix):

Squares, oh, the squares of that infinite showplace –

Paris – where Madame Lamort, the milliner,

twists and winds the unquiet ways of the world,

those endless ribbons from which she makes

these loops and ruches, rosettes and flowers and artificial fruits

all dyed with no eye for truth,

but to daub the cheap winter hats of fate.

But unlike Brigge, Rilke escapes Paris. Reflecting later, he feared that people might read his novel as seeming “to suggest that life was impossible”. Betz – who had many discussions with Rilke during the process of translating the novel – reports that the poet, accepted that the book contained “bitter reproaches [yet] it is not to life which they are addressed, on the contrary, it is the continual recognition of the following: through lack of strength, through distraction and hereditary blunders we lose practically all the innumerable riches which were destined for us on earth”. Though the Duino Elegies opens with the despairing existential cry (“Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the ranks / of the angels?”), by the seventh poem of the sequence Rilke expresses his affirmative view: “Just being here is glorious!”. In Rilke in Paris, Betz records some of Rilke’s conversations: “Instead of perpetually hesitating between action and renunciation, we fundamentally only ‘have to be there, to exist, that’s all”.

Betz’s admiration for Rilke is palpable throughout this fascinating little book. In its concluding pages, he sums up: “In seeking to express in his own way the world we thought we knew, Rilke helps us to hear more clearly what already belongs to us and permits us access to the most sinuous and iridescent forms, to profound emotive states and to that strange melody of the interior life”. This is marvellously put (and translated). Will Stone also includes a translation of a little know early sequence of prose poems by Rilke, ‘Notes on the Melody of Things’. In it, the poet reflects – through thoughts on theatrical experience and on fine art – on the relationship between background and figures in the foreground. Something of the personal angst and despair of The Notebooks can be heard in section XXXVII where we are told that “All discord and error comes when people seek to find their element in themselves, instead of seeking it behind them, in the light, in landscape at the beginning and in death”. The vastness and reality of what lies behind the solitary figure – and the negotiated relationships between the two – suggests to me that Yves Bonnefoy may well have been thinking of these pieces when he was writing L’Arriere-Pays (1972). Betz is right to conclude Rilke in Paris by praising Rilke as a poet who matured through “solitude and lucid contemplation of the loftiest problems of life”, but also one who never failed in patience or effort to express “in poetic terms the fruit of that inner quest”.

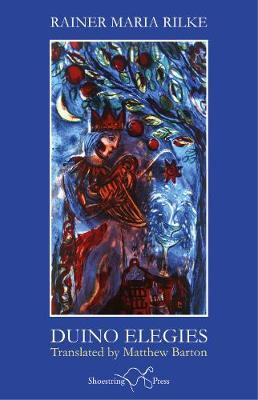

Matthew Barton himself raises the question as to whether anything could “possibly justify yet another English version” of Rilke’s Duino Elegies (1922). As someone who has contributed his own translation of the work (

Matthew Barton himself raises the question as to whether anything could “possibly justify yet another English version” of Rilke’s Duino Elegies (1922). As someone who has contributed his own translation of the work ( So Barton has now produced a lively, English version which reads well (one of his aims). Apart from a brief Introduction and a few end notes on translation issues, the poems stand on their own here – there is no parallel German text, for instance. To see the German facing Barton’s text would be interesting for most readers, even without much facility in the source language, because he does make changes to the form of the poems. It’s true Rilke’s original plays pretty fast and loose with formal metre but the changes he rings are significant and Barton has a tendency to flatten out these differences by making firm (modern-looking) stanza breaks where Rilke often continues the flow of his argument. Rilke’s form is significantly much freer in the fifth Elegy, for example. This issue of the flow of the poems – and indeed through the whole sequence of 10 poems – is one of the difficulties in translating the work. It seems to me there is a clear progression across the poems and within each individual piece. To call this an ‘argument’ may seem too logical and abstract, of course, but any translator needs to try to follow it. To declare ‘it’s poetry’ and not try to see why one image or passage follows another is giving up too easily.

So Barton has now produced a lively, English version which reads well (one of his aims). Apart from a brief Introduction and a few end notes on translation issues, the poems stand on their own here – there is no parallel German text, for instance. To see the German facing Barton’s text would be interesting for most readers, even without much facility in the source language, because he does make changes to the form of the poems. It’s true Rilke’s original plays pretty fast and loose with formal metre but the changes he rings are significant and Barton has a tendency to flatten out these differences by making firm (modern-looking) stanza breaks where Rilke often continues the flow of his argument. Rilke’s form is significantly much freer in the fifth Elegy, for example. This issue of the flow of the poems – and indeed through the whole sequence of 10 poems – is one of the difficulties in translating the work. It seems to me there is a clear progression across the poems and within each individual piece. To call this an ‘argument’ may seem too logical and abstract, of course, but any translator needs to try to follow it. To declare ‘it’s poetry’ and not try to see why one image or passage follows another is giving up too easily.

These are small points in some ways but – as I’ve said – I think Rilke is pursuing a close-grained argument in these poems (albeit via poetic utterance rather than rational discourse). Barton is also liable on occasions to shift into an overly contemporary register (Rilke tends not to 1920s speech patterns but rather a Classically influence idiolect of his own). He replaces Rilke’s “wehe” which really is ‘alas’ with phrases like “god help me” or “heaven help us” which again propel the tone towards the personal (a rather English, bourgeois personal). In the ninth Elegy, Rilke is disparaging about the thin gruel of conventional human happiness in the face of death: “dieser voreilige Vorteil eines nahen Verlusts”. Mitchell translates this as “that too-hasty profit snatched from impending loss”. Barton tries a bit too hard with, “[this] is merely / easy credit with a looming payback date”. The same happens in the tenth Elegy, where Rilke is describing contemporary society’s shallow distractions from the fact of death. He describes; “die Kirche begrenzt, ihre fertig gekaufte: / reinlich und zu und enttäuscht wie ein Postamt am Sonntag”. Mitchell again: “bounded by the church with its ready-made consolations: / clean and disenchanted and shut as a post-office on Sunday”. Barton changes, up-dates, Americanises and so loses some of the irony: “the flatpack church, all safe and clean and shut / and dreary as an empty parking lot”.

These are small points in some ways but – as I’ve said – I think Rilke is pursuing a close-grained argument in these poems (albeit via poetic utterance rather than rational discourse). Barton is also liable on occasions to shift into an overly contemporary register (Rilke tends not to 1920s speech patterns but rather a Classically influence idiolect of his own). He replaces Rilke’s “wehe” which really is ‘alas’ with phrases like “god help me” or “heaven help us” which again propel the tone towards the personal (a rather English, bourgeois personal). In the ninth Elegy, Rilke is disparaging about the thin gruel of conventional human happiness in the face of death: “dieser voreilige Vorteil eines nahen Verlusts”. Mitchell translates this as “that too-hasty profit snatched from impending loss”. Barton tries a bit too hard with, “[this] is merely / easy credit with a looming payback date”. The same happens in the tenth Elegy, where Rilke is describing contemporary society’s shallow distractions from the fact of death. He describes; “die Kirche begrenzt, ihre fertig gekaufte: / reinlich und zu und enttäuscht wie ein Postamt am Sonntag”. Mitchell again: “bounded by the church with its ready-made consolations: / clean and disenchanted and shut as a post-office on Sunday”. Barton changes, up-dates, Americanises and so loses some of the irony: “the flatpack church, all safe and clean and shut / and dreary as an empty parking lot”. Lieke Marsman’s The Following Scan Will Last Five Minutes (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019) is an unlikely little gem of a book about cancer, language, poetry, Dutch politics, philosophy, the environment, the art of translation and friendship – all bound together by a burning desire (in both original author and her translator, Sophie Collins) to advocate the virtues of empathy. The PBS have chosen it as their Summer 2019 Recommended Translation.

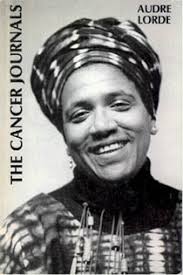

Lieke Marsman’s The Following Scan Will Last Five Minutes (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019) is an unlikely little gem of a book about cancer, language, poetry, Dutch politics, philosophy, the environment, the art of translation and friendship – all bound together by a burning desire (in both original author and her translator, Sophie Collins) to advocate the virtues of empathy. The PBS have chosen it as their Summer 2019 Recommended Translation. The sort of silence Lorde fears is evoked in the monitory opening poem. Its unusual, impersonal narration is acutely aware of the lure of sinking away into the “morphinesweet unreality of the everyday”, of the allure of self-imposed isolation (“unplugg[ing] your router”) in the face of the diagnosis of disease. What the voice advises is the recognition that freedom consists not in denial, in being free of pain or need, but in being able to recognise our needs and satisfy them: “to be able to get up and go outside”. It’s this continuing self-awareness and the drive to try to achieve it that Marsman hopes for and (happily) comes to embody. But it was never going to be easy and towards the end of the poem sequence, these needs are honed to the bone:

The sort of silence Lorde fears is evoked in the monitory opening poem. Its unusual, impersonal narration is acutely aware of the lure of sinking away into the “morphinesweet unreality of the everyday”, of the allure of self-imposed isolation (“unplugg[ing] your router”) in the face of the diagnosis of disease. What the voice advises is the recognition that freedom consists not in denial, in being free of pain or need, but in being able to recognise our needs and satisfy them: “to be able to get up and go outside”. It’s this continuing self-awareness and the drive to try to achieve it that Marsman hopes for and (happily) comes to embody. But it was never going to be easy and towards the end of the poem sequence, these needs are honed to the bone:

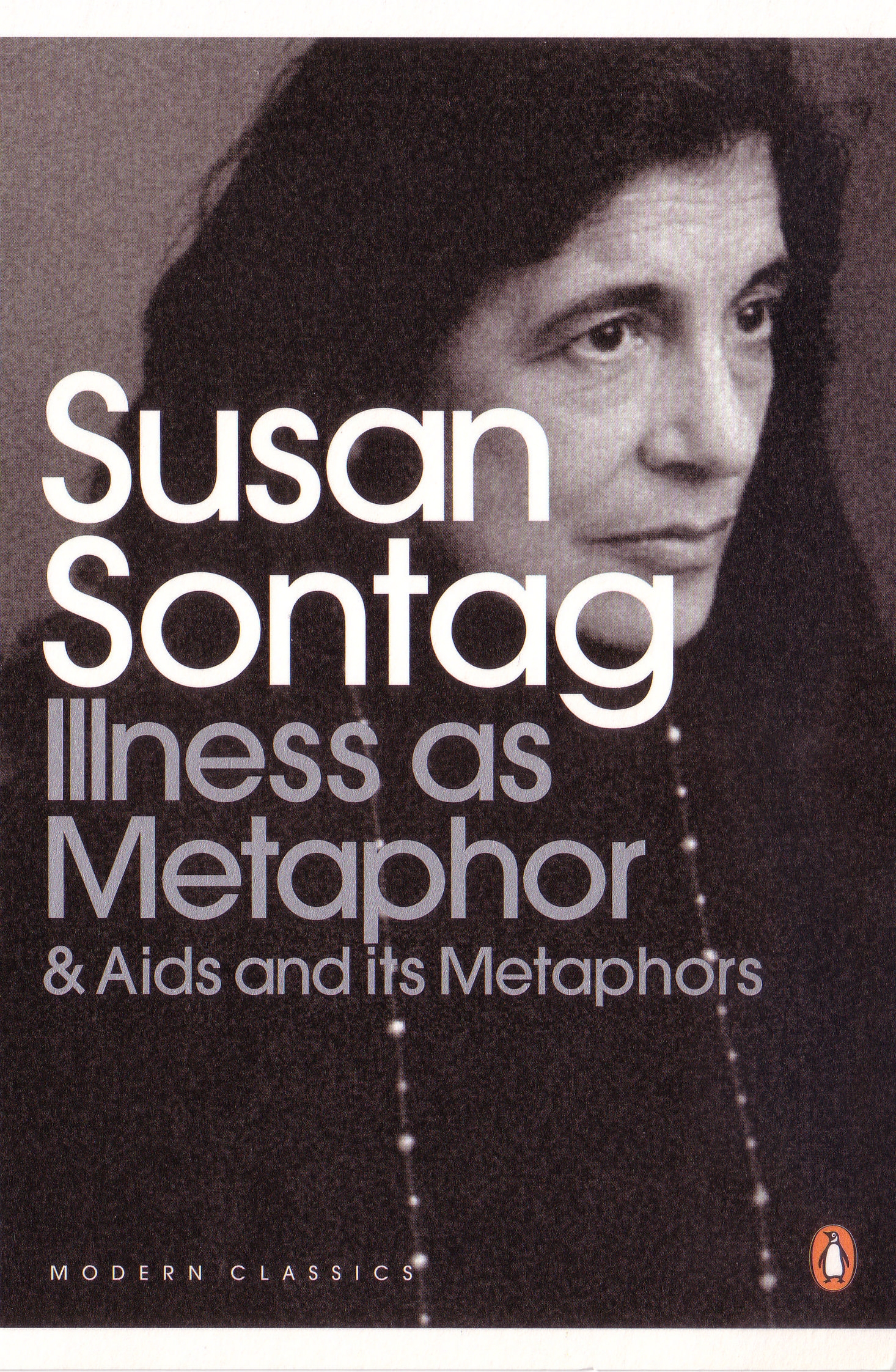

Marsman tells us she read Audre Lorde and Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor after her operation and discharge from hospital. It’s Sontag who draws attention to the role of language in the way patients themselves and other people respond to cancer. Marsman asks herself: “Am I experiencing this cancer as an Actual Hell [. . .] or because that is the common perception of cancer?” The implied failure to achieve truly empathetic perception of the role and nature of the disease is echoed horribly in the empathetic failures and hypocrisies of Dutch politicians (UK readers will find this stuff all too familiar in our own politics). Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, blithely allocates billions of euros to multinationals like Shell and Unilever (on no valid basis) while overseeing cuts in health services. Marsman reads this as a failure to empathise with the ill. Another politician, Klaas Dijkhoff, reduces benefits on the basis that people encountering “bad luck” need to get themselves back on their own two feet. Bad luck here includes illness, disability, being born into poverty or abusive families, being compelled to flee your own country. Marsman’s own encounter with such ‘bad luck’ makes her rage all the more incandescent.

Marsman tells us she read Audre Lorde and Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor after her operation and discharge from hospital. It’s Sontag who draws attention to the role of language in the way patients themselves and other people respond to cancer. Marsman asks herself: “Am I experiencing this cancer as an Actual Hell [. . .] or because that is the common perception of cancer?” The implied failure to achieve truly empathetic perception of the role and nature of the disease is echoed horribly in the empathetic failures and hypocrisies of Dutch politicians (UK readers will find this stuff all too familiar in our own politics). Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, blithely allocates billions of euros to multinationals like Shell and Unilever (on no valid basis) while overseeing cuts in health services. Marsman reads this as a failure to empathise with the ill. Another politician, Klaas Dijkhoff, reduces benefits on the basis that people encountering “bad luck” need to get themselves back on their own two feet. Bad luck here includes illness, disability, being born into poverty or abusive families, being compelled to flee your own country. Marsman’s own encounter with such ‘bad luck’ makes her rage all the more incandescent.

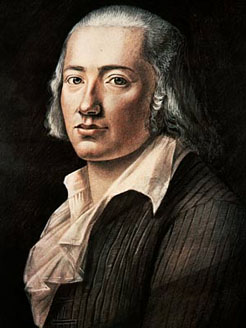

Waiblinger was a real Holderlin fan. The older poet’s novel, Hyperion, had appeared in 1822

Waiblinger was a real Holderlin fan. The older poet’s novel, Hyperion, had appeared in 1822