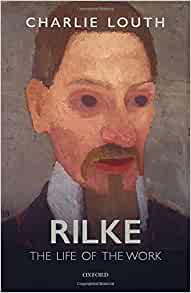

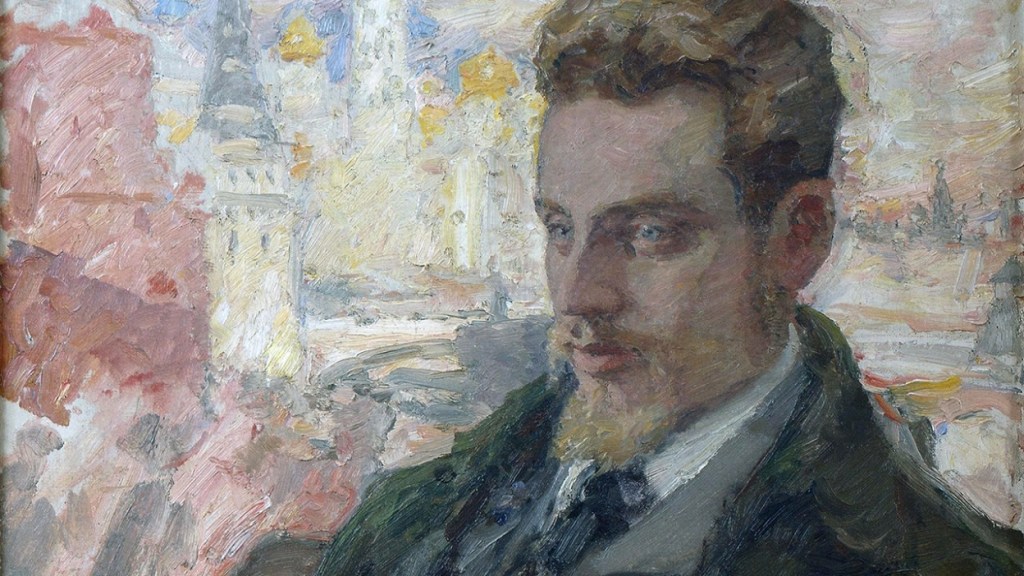

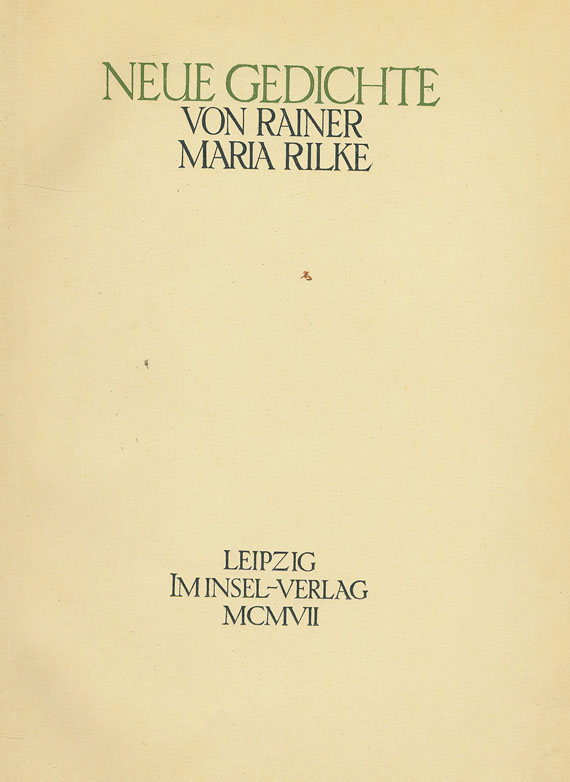

As I mentioned in my last blog post, much of my time through lockdown and in the last few months has been taken up with translation. One of these projects is as daunting as it is exciting. Pushkin Press have commissioned me to complete a new selection and translation of the work of Rainer Maria Rilke to appear in 2023. Some of you will be aware of my earlier published versions of the Duino Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus (both available from Enitharmon Press). The new project will contain selections from those sequences and a good selection of earlier poems, including from the New Poems. As well as trying out a few of my new translations in this post (and the following one), the body of it is an uncut version of my recent review of Charlie Louth’s excellent book on Rilke, Rilke: the Life of the Work (OUP, 2020). A shorter version of this review appeared in the latest Agenda magazine, ‘Altered Distances’ (Vol 54, Nos. 1/2). Many thanks to the editor, Patricia McCarthy for asking me to write it.

Part I

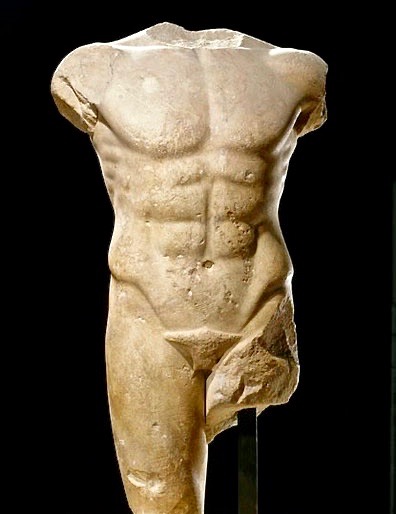

Rilke has long suffered from two types of criticism. Among his enthusiasts, some declare his work close to sacred and therefore hardly open to ‘normal’ practices of critical analysis, at risk of spoiling the ‘bloom’ of mystery they find there. Others, of a more negative inclination, accuse him of an aloof aestheticism, a likely fatal distance from ‘real’ life. One such was Thomas Mann who can be found, Charlie Louth notes, “(rather richly) calling him an ‘arch aesthete’”. Both viewpoints risk downplaying the skilled crafting of Rilke’s work (he thought long and hard about poems as artefacts, things consciously and intricately made) but also risk mistaking the particular power of his poetry. Rilke: the Life of the Work is comprehensive, erudite, always clear and – most importantly – keeps returning us to the poetry to which Louth enthusiastically responds: “When we read Rilke, the poems do not feel aloof, and they do not feel merely aesthetic in their claims. They press upon us and make us examine ourselves, and they help us experience our life in the world with greater clarity and depth”. Most readers will recognise this as an allusion to the ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’ (from New Poems) which concludes “You must change your life”. Louth again: “It is unusual for Rilke to be so direct, but as I see it a similar spirit animates most if not all of his poems”.

This book aims to bridge the gulf between enthusiastic, non-specialist readers of poetry (Louth translates his foreign language quotations himself) and the German lang/lit academic and student. The balance between engaged readability and academic thoroughness is very well judged. I particularly value Louth’s close readings of ‘the work’, viewed as objectively as possible (Louth declares early on that he has no “overarching thesis”). There are other readily available biographical and critical works, but the strength of Rilke: the Life of the Work is that, with its discussion of the formal choices, wording and syntax of so many poems, it is a comprehensive attempt at ‘Reading Rilke’. The structure of the book’s 600 pages is primarily chronological, from the poet’s earliest publication, Lives and Songs (1894) through to Vergers (1926). Louth only departs from this chronological survey twice. Early on, he looks at several poems that open Rilke’s published books, then, in Chapter 6, he discusses the four poems Rilke wrote as requiems.

So Louth’s Rilke is a craftsman and moralist who urges us to live better. The kind of closed system of a purely aesthetic art was the poet’s abhorrence. In a lecture he gave early in his career, Rilke is already sure that “‘art is only a path, not a destination’. In a letter to Lou Andreas-Salomé in 1903 he confirms: ‘I do not want to tear art and life apart; I know that in the end they are one and the same’. As so often, Louth articulates his subject’s attitude with great clarity: “for Rilke, there can be no question of shutting oneself away from life, of retreating into the work, and the desk, if it is to be the place of necessary writing, must be a ‘vitale Mitte’, a site right in the middle of life and exposed to all its risks and promises. To write is not to withdraw but precisely to engage”.

Rilke’s poetry pays particular attention to the processes of change associated with being human. Poems record such moments of change but also act, in the process of being read and openly experienced, as opportunities where change in an individual might take place. For those with faith in literature, Louth articulates the exciting prospect: “to read at all is to pause, is to take your time in times when an anxious haste pervades much of what we do. In some sense it is to live better whether poetry makes anything happen or not”. Writing to Thankmar von Münchhausen in 1915, Rilke asks, “What is our job if not, purely and freely, to provide occasions for change?” Louth finds these ideas in ‘Eingang’ / ‘Entrance’, one of the poems Rilke placed at the start of The Book of Images (1902/06). The furniture of this poem – the self, a house, a tree – is a grouping that recurs throughout Rilke’s work and what interests him is the suggestion that, as we leave the familiarity of our house, “the house of our habits, we enter the imaginary space of another building [. . .] coming from life into the poem, and passing through the poem into life”. Here is my new translation of this poem:

Whoever you are: in the evening, step out

of your living room, from all that’s familiar;

in the distance, the last thing, your house:

no matter who you are.

And although your eyes have grown so weary

you can barely lift them from the worn threshold,

slowly, with them, you still raise a black tree

and set it before the sky: lean and alone.

And you have made a world. And it is immense,

like a word, in silence, it continues to grow.

And as your will grasps its significance,

so your eyes, tenderly, let it go . . .

For Rilke’s own life and work, the key meeting was with Lou Andreas-Salomé in May 1897. Lou changed his handwriting and his name (from René to Rainer), but it was the confidence and groundedness in the world that she brought to his life that pushed his art “closer to the details of lived experience”. Rilke himself wrote: “The world lost its cloudiness [. . .] I learnt a simplicity, learnt slowly and laboriously how simple everything is, and I gained the maturity to talk of simple things”. Lou’s influence can be seen in the lecture he gave in Prague in 1898, where he distances himself from Symbolism and aestheticism (the dominant strands of ‘modern poetry’ at the turn of the century) to argue that the artist must not be “shut out of the great channel of life”, but must evoke the constant dialogue between the individual and things, “the strange coincidences between inner and outer out of which experience is made”. As Louth says, this is an early statement of the theme which will occupy his whole life.

Here is a brief poem – actually naming Lou and indicating her influence in persuading Rilke of the sacredness of the ordinary. It went unpublished for years, but was part of Rilke’s sequence called To Celebrate You (Dir zur Feier):

The rain runs its chilly fingers

down our windows, unseeing;

we lean back in deep armchairs

and listen, as if the quiet hours

dripped from a weary mill all evening.

x

And then Lou speaks. Our souls incline

one to another. Even cut flowers

at the window nod their topmost bloom

and we are completely at home,

here in this tranquil, white house.

For Rilke, the successful poem is a space in which the mysteries of things and personal confession are both explored, or revealed, simultaneously. Louth argues that, from the outset, Rilke’s view of this was always positive: “there is no unnerving consciousness of the self ’s arbitrary dependence on chance encounters with the outside world”, but equally, there is “no doubt about the existence of an underlying unity to which the poet has access”. What he feared was ‘the interpreted world’ (‘der gedeuteten Welt’), a world view shorn of all mystery, a perspective that perhaps most of us inhabit, a view in which language has become dominantly instrumental, “narrowing our vision so that life appears cut and dried without any possibility of the unknown and the unknowable”. Louth explains what readers of Rilke value in his work: “poetic language, as he understands it, is precisely a way of talking that avoids directness and allows the mutability of experience and the mystery of the world to be expressed. It releases rather than limits possibility”. Beyond this stands what Rilke might have meant by the term ‘God’. ‘He’ is “an experience of totality, life felt as a whole, in which self and other are not distinct or momentarily lose their distinctness”.

Here is my new translation of an early poem from The Book of Hours (Das Stundenbuch) in which Rilke is developing these ideas:

You, the darkness from which I came,

I love you more than the flame

scoring the world’s edge

with a glimmer

upon some sphere,

beyond which no-one has more knowledge.

x

Yet the darkness binds everything into itself:

all forms, flames, creatures, myself,

it seizes on them,

all powers, everything human . . .

x

And it may be: there is an immense might

stirring nearby –

x

I believe in the night.

It is in part because the enemy of mystery is language (too casually used) that poetry (constructed from language more carefully used) has an advantage over other art forms like painting. There’s an irony here, of course, because Rilke learned so much from other workers in the fine arts. Most know about the debt he owed to Rodin and Cezanne, but Louth argues Rilke’s journey towards the poetics of the New Poems began in the period he resided in the artists’ community in Germany at Worpswede. A lot of his thinking there concerned images of man and landscape. For the majority of the time, humans and nature live “side-by-side with hardly any knowledge of one another” and it is in the ‘as if’ of the work of art that they can be brought closer, into a more conscious relation. But because a poem works through time, such a correspondence is acknowledged as “something one traverses and gains knowledge of but cannot hold onto”.

Part 2 of this review coming next week…..

David Pollard’s book is divided into three sections, one each on Parmigianino, Rembrandt and Caravaggio. Initially, Pollard presents a set of 15 self-declared “meditations” on a single work of art – Parmigianino’s ‘Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror’ (c. 1524). This is a bold move, given that John Ashbery did the same thing in 1974 and Pollard does explore ideas also found in Ashbery’s poem. Both writers are intrigued by a self-portrait painted onto a half-spherical, contoured surface to simulate a mirror such as was once used by barbers. The viewer gazes at an image of a mirror in which is reflected an image of the artist’s youthful and girlish face. It’s this sense of doubling images – an obvious questioning of what is real – that Pollard begins with. “You are a double-dealer” he declares, addressing the artist directly, though the language is quickly thickened and abstracted into a less than easy, philosophical, meditative style. It is the paradoxes that draw the poet: “you allow the doublings / inherent in your task to hide themselves / in open show, display art that / understands itself too well”. Indeed, this seems to be something of a definition of art for Pollard. “Let us be clear”, he says definitively, though the irony lies in the fact that such art asks questions about clarity precisely to destabilise it.

David Pollard’s book is divided into three sections, one each on Parmigianino, Rembrandt and Caravaggio. Initially, Pollard presents a set of 15 self-declared “meditations” on a single work of art – Parmigianino’s ‘Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror’ (c. 1524). This is a bold move, given that John Ashbery did the same thing in 1974 and Pollard does explore ideas also found in Ashbery’s poem. Both writers are intrigued by a self-portrait painted onto a half-spherical, contoured surface to simulate a mirror such as was once used by barbers. The viewer gazes at an image of a mirror in which is reflected an image of the artist’s youthful and girlish face. It’s this sense of doubling images – an obvious questioning of what is real – that Pollard begins with. “You are a double-dealer” he declares, addressing the artist directly, though the language is quickly thickened and abstracted into a less than easy, philosophical, meditative style. It is the paradoxes that draw the poet: “you allow the doublings / inherent in your task to hide themselves / in open show, display art that / understands itself too well”. Indeed, this seems to be something of a definition of art for Pollard. “Let us be clear”, he says definitively, though the irony lies in the fact that such art asks questions about clarity precisely to destabilise it. The 15 meditations are in free verse, the line endings often destabilising the sense, and they are lightly punctuated when I could have done with more conventional punctuation given the complex, involuted style. Pollard also likes to double up phrases, his second attempt often shifting ground or seeming propelled more by sound than sense. This is what the blurb calls Pollard’s “dense and febrile language” and it is fully self-conscious. In meditation 15, he observes that the artist’s paint is really “composed of almost nothing like words / that in their vanishings leave somewhat / of their meaning” – a ‘somewhat’ that falls well short of anything definitive. Of course, this again echoes Ashbery and appeals to our (post-)modern sensibility. Pollard images such a sense of loss with “a rustle of leaves among the winds / of autumn blowing in circles / back into seasons of the turning world”. He does not possess Ashbery’s originality of image, as here deploying the cliched autumnal leaves and then echoing Eliot’s “still point of the turning world”. Indeed, many poems are frequently allusive (particularly of Shakespearean phrases, Keats coming a close second) and for me this does not really work, the phrases striking as undigested shorthand for things that ought to be more freshly said.

The 15 meditations are in free verse, the line endings often destabilising the sense, and they are lightly punctuated when I could have done with more conventional punctuation given the complex, involuted style. Pollard also likes to double up phrases, his second attempt often shifting ground or seeming propelled more by sound than sense. This is what the blurb calls Pollard’s “dense and febrile language” and it is fully self-conscious. In meditation 15, he observes that the artist’s paint is really “composed of almost nothing like words / that in their vanishings leave somewhat / of their meaning” – a ‘somewhat’ that falls well short of anything definitive. Of course, this again echoes Ashbery and appeals to our (post-)modern sensibility. Pollard images such a sense of loss with “a rustle of leaves among the winds / of autumn blowing in circles / back into seasons of the turning world”. He does not possess Ashbery’s originality of image, as here deploying the cliched autumnal leaves and then echoing Eliot’s “still point of the turning world”. Indeed, many poems are frequently allusive (particularly of Shakespearean phrases, Keats coming a close second) and for me this does not really work, the phrases striking as undigested shorthand for things that ought to be more freshly said.

In fact, the woman is hardly given a voice and the substance of the sequence is dominated by the (male) artist’s reflections on his years-long task. He’s most often found “between this scaffold floor and ceiling”, complaining about his “craned neck”, pouring plaster, crushing pigments, enumerating at great length the qualities and shades of the paint he employs (Cashman risking an odd parody of a Dulux colour chart at times – “Variety is my clarity, / purity my colour power”). Later, we hear him complaining the plaster will not dry in the cold winter months. We even hear the artist reflecting on his own features, the famous “long white beard and beak-like nose”. These period and technical details work well, but Cashman’s Michelangelo sometimes also shades interestingly into a more future-aware voice, melding – I think – with the poet’s own voice. So he remarks: “Getting lost is not a condition men like me endure or venture on today. / All GPS and mobile interlinks enmesh our every step”. Later, a list of “everything there is” sweepingly includes “chair, man, woman; laptop or confession box”.

In fact, the woman is hardly given a voice and the substance of the sequence is dominated by the (male) artist’s reflections on his years-long task. He’s most often found “between this scaffold floor and ceiling”, complaining about his “craned neck”, pouring plaster, crushing pigments, enumerating at great length the qualities and shades of the paint he employs (Cashman risking an odd parody of a Dulux colour chart at times – “Variety is my clarity, / purity my colour power”). Later, we hear him complaining the plaster will not dry in the cold winter months. We even hear the artist reflecting on his own features, the famous “long white beard and beak-like nose”. These period and technical details work well, but Cashman’s Michelangelo sometimes also shades interestingly into a more future-aware voice, melding – I think – with the poet’s own voice. So he remarks: “Getting lost is not a condition men like me endure or venture on today. / All GPS and mobile interlinks enmesh our every step”. Later, a list of “everything there is” sweepingly includes “chair, man, woman; laptop or confession box”.

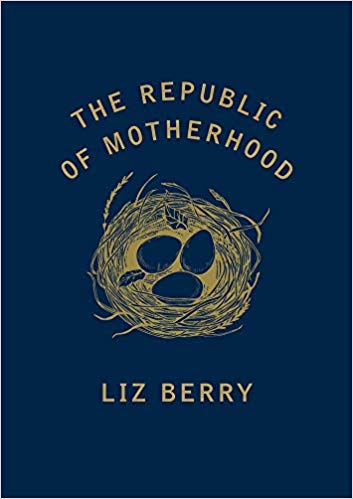

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

The next section of the poem displays some of Lorca’s startling, surprising images: the “stars of frost”, the “fish of shadows”, the fig-tree’s “sandpaper branches”, the mountain is a “a thieving cat” that “bristles its sour agaves”. These are good examples of Lorca’s technique with metaphor: to place together two things which had always been considered as belonging to two different worlds, and in that fusion and shock to give them both a new reality. But these lines are perhaps really more about raising the narrative tensions in the poem through rhetorical questions such as, “But who will come? And where from?”

The next section of the poem displays some of Lorca’s startling, surprising images: the “stars of frost”, the “fish of shadows”, the fig-tree’s “sandpaper branches”, the mountain is a “a thieving cat” that “bristles its sour agaves”. These are good examples of Lorca’s technique with metaphor: to place together two things which had always been considered as belonging to two different worlds, and in that fusion and shock to give them both a new reality. But these lines are perhaps really more about raising the narrative tensions in the poem through rhetorical questions such as, “But who will come? And where from?” So up they climb. We don’t know why, but the atmosphere here is dripping with ill omen: they are “leaving a trail of blood, / leaving a trail of tears”. Then there is another of Lorca’s images yoking together unlikely items. As they climb to the roof-tiles, there is a trembling or quivering of “tiny tin-plate lanterns” and perhaps it’s this that becomes the sound of a “thousand crystal tambourines / [that] wound the break of day”. Lorca himself chose this image to comment on in his talk. He says if you ask why he wrote it he would tell you: “I saw them, in the hands of angels and trees, but I will not be able to say more; certainly I cannot explain their meaning”. I hear Andre Breton there, or Dali refusing to ‘explain’ the images of the truly surreal work. In each case the interpretative labour is handed over to us.

So up they climb. We don’t know why, but the atmosphere here is dripping with ill omen: they are “leaving a trail of blood, / leaving a trail of tears”. Then there is another of Lorca’s images yoking together unlikely items. As they climb to the roof-tiles, there is a trembling or quivering of “tiny tin-plate lanterns” and perhaps it’s this that becomes the sound of a “thousand crystal tambourines / [that] wound the break of day”. Lorca himself chose this image to comment on in his talk. He says if you ask why he wrote it he would tell you: “I saw them, in the hands of angels and trees, but I will not be able to say more; certainly I cannot explain their meaning”. I hear Andre Breton there, or Dali refusing to ‘explain’ the images of the truly surreal work. In each case the interpretative labour is handed over to us. Did they know this? It appears not. But who is she? Daughter? Lover? Both? Is this really what the two men find there? For sure, there is some mystery about the chronology because the seeming explanation of the killing is couched as a flashback: “The dark night grew intimate / as a cramped little square. / Drunken Civil Guards / were hammering at the door”. But Lorca often plays fast and loose with verb tenses. Was this earlier? Were they in search of the rebellious youth? But they found his girl-friend? Hanging her on the rooftop? Is the house owner her father? Does he know what has happened? Is this why his house is not his own anymore? Is this why he is no more what he was?

Did they know this? It appears not. But who is she? Daughter? Lover? Both? Is this really what the two men find there? For sure, there is some mystery about the chronology because the seeming explanation of the killing is couched as a flashback: “The dark night grew intimate / as a cramped little square. / Drunken Civil Guards / were hammering at the door”. But Lorca often plays fast and loose with verb tenses. Was this earlier? Were they in search of the rebellious youth? But they found his girl-friend? Hanging her on the rooftop? Is the house owner her father? Does he know what has happened? Is this why his house is not his own anymore? Is this why he is no more what he was? The only certain thing is that the poem does not reply. It ends with a recurrence of that opening yearning – now it’s read as a more obviously grieving voice – though it’s not necessarily to be read as the young man’s voice. It’s the ballad voice, the one I took so long to really grasp in Lorca’s work. It is a voice involved and passionate but with wider geographical, political and historical horizons beyond the individual incident. Like Auden’s ploughman in ‘Musee des Beaux Arts’, glimpsing Icarus’ fall from the sky, yet he must get on with his work, ‘Sleepingwalking Ballad’ returns us in its final lines to the wider world:

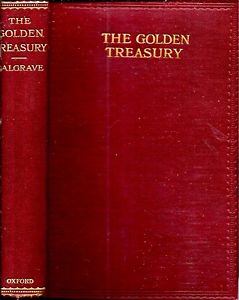

The only certain thing is that the poem does not reply. It ends with a recurrence of that opening yearning – now it’s read as a more obviously grieving voice – though it’s not necessarily to be read as the young man’s voice. It’s the ballad voice, the one I took so long to really grasp in Lorca’s work. It is a voice involved and passionate but with wider geographical, political and historical horizons beyond the individual incident. Like Auden’s ploughman in ‘Musee des Beaux Arts’, glimpsing Icarus’ fall from the sky, yet he must get on with his work, ‘Sleepingwalking Ballad’ returns us in its final lines to the wider world: The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

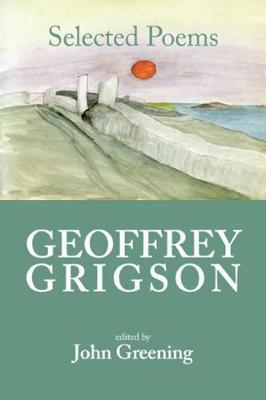

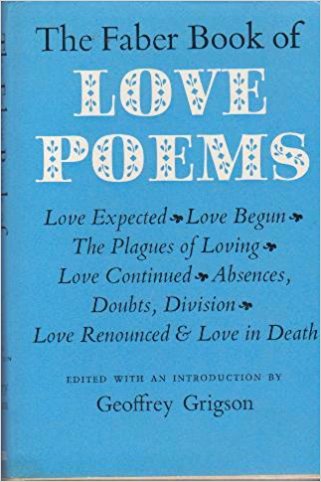

*As a labouring translator myself, I have long remembered Grigson’s brilliant put-down in his Introduction to the Faber Book of Love Poems (1973). Explaining why he has not included any translations at all, he declares that their “unmeasured, thin-rolled short crust” would prove detrimental to the health of the nation’s poetic taste. Times have changed, thank goodness.

*As a labouring translator myself, I have long remembered Grigson’s brilliant put-down in his Introduction to the Faber Book of Love Poems (1973). Explaining why he has not included any translations at all, he declares that their “unmeasured, thin-rolled short crust” would prove detrimental to the health of the nation’s poetic taste. Times have changed, thank goodness.![1074-Poetry-Review_Cover-RGB-300-w-shadow-429x600[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1074-poetry-review_cover-rgb-300-w-shadow-429x6001.jpg)

![jellyfish[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jellyfish1.jpg)

![alpine-skiing-877410_640[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/alpine-skiing-877410_6401.jpg)

![p045rwch[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/p045rwch1.jpg)

![train[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/train1.jpg)

![DuncanForbes-200x245[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/duncanforbes-200x2451.jpg)

![blogcharlescausley2[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/blogcharlescausley21.jpg)

![wp2f72b580_06[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/wp2f72b580_061.png)