As in the previous four years, I am posting – over the summer – my reviews of the 5 collections chosen for the Forward Prizes Felix Dennis award for best First Collection. This year’s £5000 prize will be decided on Sunday 20th October 2019. Click on this link to access all 5 of my reviews of the 2018 shortlisted books (eventual winner Phoebe Power), here for my reviews of the 2017 shortlisted books (eventual winner Ocean Vuong), here for my reviews of the 2016 shortlisted books (eventual winner Tiphanie Yanique), here for my reviews of the 2015 shortlisted books (eventual winner Mona Arshi).

The full 2019 shortlist is:

Raymond Antrobus – The Perseverance (Penned in the Margins)

Jay Bernard – Surge (Chatto & Windus)

David Cain – Truth Street (Smokestack Books) – reviewed here.

Isabel Galleymore – Significant Other (Carcanet)

Stephen Sexton – If All the World and Love Were Young (Penguin Books)

Isabel Galleymore’s Significant Other cuts incisively and deliciously against several fashionable poetic grains in being committed yet dispassionate, quietly concise not shrill, impersonal rather than nakedly biographical. In Carcanet’s blurb, Rachael Boast praises the book for its “simplicity, empathy and sheer Blakean joy”; in truth, it needs to be praised for far tougher virtues such as its probing intelligence, its metaphorical brilliance, its lover’s relational sense of angst. Galleymore certainly possesses an astounding gift for figurative language. It’s tempting to allude to Craig Raine’s Martianism in this context, though Galleymore interrogates the metaphorical process in far more important and interesting ways.

Isabel Galleymore’s Significant Other cuts incisively and deliciously against several fashionable poetic grains in being committed yet dispassionate, quietly concise not shrill, impersonal rather than nakedly biographical. In Carcanet’s blurb, Rachael Boast praises the book for its “simplicity, empathy and sheer Blakean joy”; in truth, it needs to be praised for far tougher virtues such as its probing intelligence, its metaphorical brilliance, its lover’s relational sense of angst. Galleymore certainly possesses an astounding gift for figurative language. It’s tempting to allude to Craig Raine’s Martianism in this context, though Galleymore interrogates the metaphorical process in far more important and interesting ways.

Her main subject is the natural world and our relationship with it and the book is studded with a number of bravura pieces which – as Ted Hughes put it in Poetry in the Making (Faber, 1967) – manage to ‘capture’ something of creaturely lives. But rather than foxes and hawks, Galleymore writes about starfish, mussels, slipper limpets, goose barnacles, seahorses, whelks, frogs, spiny cockles and crabs. As Hughes’ versions of the natural world – even a harebell or snowdrop – tended towards violence, Galleymore’s creatures tend toward sensuality and – even when the behaviour is predatory – the descriptions have a sexual quality to them. So the starfish’s attack on a mussel rises to a climax when

[. . . ] the mussel’s jaw

drops a single millimetre. Into this cleft

she’ll press the shopping bag of her stomach

and turn the mollusc into broth.

There is indeed a sort of empathy here but, at its best, this kind of metaphorical language – the shopping bag, the broth – is accurately based on precise observation of actual behaviours.

But Galleymore also sees dangers. In her 2014 Worple Press pamphlet, Dazzle Ship, the poem ‘Forest’ sought to limit such likening of one thing to another: “It shouldn’t go further / than this flirt and rumour”. The consequence of this failure of (for want of a better word) tact is itself imaged in the sloth that mistakes her own limb for “an algae-furred branch” and plummets “through the tangle / of the forest canopy // holding only onto herself”. ‘Forest’ is not included in Significant Other, but a closely related image occurs in ‘Once’. This little poem tracks human relations with nature from our early fears of “being eaten”, through the beginnings of farming, the awakening of metaphors comparing ourselves to Nature, towards the Romantic notion of being “at one”. Yet often there is a bullying, colonising quality to such a sense of oneness – we co-opt Nature into our world on our own terms. In ‘Once’, we are “at one and lost / as the woman wrapped in her lover’s arms / who accidentally kisses herself”. Such ludicrous, solipsistic love-making echoes the sloth’s mistake and downfall.

But Galleymore also sees dangers. In her 2014 Worple Press pamphlet, Dazzle Ship, the poem ‘Forest’ sought to limit such likening of one thing to another: “It shouldn’t go further / than this flirt and rumour”. The consequence of this failure of (for want of a better word) tact is itself imaged in the sloth that mistakes her own limb for “an algae-furred branch” and plummets “through the tangle / of the forest canopy // holding only onto herself”. ‘Forest’ is not included in Significant Other, but a closely related image occurs in ‘Once’. This little poem tracks human relations with nature from our early fears of “being eaten”, through the beginnings of farming, the awakening of metaphors comparing ourselves to Nature, towards the Romantic notion of being “at one”. Yet often there is a bullying, colonising quality to such a sense of oneness – we co-opt Nature into our world on our own terms. In ‘Once’, we are “at one and lost / as the woman wrapped in her lover’s arms / who accidentally kisses herself”. Such ludicrous, solipsistic love-making echoes the sloth’s mistake and downfall.

Several commentators have picked out ‘Choosing’ as a significant poem in this book, most seem to take its statement about loving all “eight million differently constructed hearts” (the number of species currently living on earth) as a genuine example of environmental good practice. But there is irony at work here when the poem goes on to indicate the difficulty of achieving such a multiplicity of loves, using incomplete statements, awkward repetitions and – as Galleymore often does – the language of human lovers to express it. So:

To say nothing will come between us,

to stay benignly intimate was –

sometimes not calling was easier –

sometimes I’d forget to touch you

and you, and you [. . .]”

And these inevitable failures to live up to such ideally multivalent webs of relationships lead to “breakups” (in the lover’s parlance) which I take to mean extinctions (biologically speaking):

like the others it seemed you’d just popped out

for a pint of milk and now

nothing’s conjured hearing your name

So Galleymore sees figurative language not only in poetic terms, but also as its shapes all human knowledge. ‘Uprising’ (also in Dazzle Ship only) compares the fluffy seed-head of a dandelion to a microphone, ready to transmit “a hundred / smaller scaffoldings // of a thought or an idea”. But such likening of one thing to another (when taken beyond flirt and rumour) like any human relationship is at risk of an unbalanced power dynamic. ‘Seahorse’ is unusual in this collection, opening as it does in the human world, in a restaurant, a man speaking for the woman he’s with, his presumption described as “shocking”. Yet the narrator seems complicit in such a relationship too:

like a hand shaping itself inside another’s

the way my hand tucks into his

like a difference pretending it’s not.

Like two separate identities, one pretending not to be really separate at all. Or not being allowed to regard itself as separate at all. This is close to metaphor as a form of gaslighting.

In several poems, Nature is the exploited, submissive partner but in ‘No Inclination’ it is shown fighting back. The metaphors we have long used to domesticate and describe the natural world are shown to be breaking down:

[. . .] a surprising number of gales

didn’t know what it was to howl.

The woebegone voice of the willow

confirmed it had no reason to weep.

It is our presumptuous, mansplaining tendency not to see Nature for what it is – but only in our own invented metaphors for it – that contributes to our planet’s endangerment. Our assumption of the benign, life-giving smile of the sun (Telly Tubbies anyone?) is not something we can rely on for much longer (record UK temperatures anyone?):

It couldn’t be denied: that fiery mass

possessed no inclination to smile.

Household after household poured

whiskey-cokes to toast the news,

the ice melting fast in their drinks.

In ‘Significant Other’ itself, a cloud may be likened to a tortoise but the cocktail of power and presumption is complex; the relationship is not reciprocal. As the tortoise owner once erroneously anthropomorphised her pet, so in later life she mistook her lover’s sexual fidelity. The truth is not always as we wish it or as our metaphors construct it. At the close of the poem, the tortoise continues in its own “tortoisey” way, resisting any further efforts to colonise it, to humanise it. It is and remains significantly Other. And in this cool-toned, often fascinating book, Galleymore knows the Other needs to be allowed its distance, allowed its dynamic, changeable difference, its wealth of richness in being different, whether that Other is a lover or the natural world itself:

In ‘Significant Other’ itself, a cloud may be likened to a tortoise but the cocktail of power and presumption is complex; the relationship is not reciprocal. As the tortoise owner once erroneously anthropomorphised her pet, so in later life she mistook her lover’s sexual fidelity. The truth is not always as we wish it or as our metaphors construct it. At the close of the poem, the tortoise continues in its own “tortoisey” way, resisting any further efforts to colonise it, to humanise it. It is and remains significantly Other. And in this cool-toned, often fascinating book, Galleymore knows the Other needs to be allowed its distance, allowed its dynamic, changeable difference, its wealth of richness in being different, whether that Other is a lover or the natural world itself:

‘I Keep You’

at a difference:

a thought I won’t allow myself

to think for thinking

it’s a matter of time

till you, a cargo

ship of foreign goods,

cross my kitchen table

like a butter dish.

Cain also cites the work of Charles Reznikioff and Svetlana Alexievich as models. The former, an Objectivist poet, developed work from

Cain also cites the work of Charles Reznikioff and Svetlana Alexievich as models. The former, an Objectivist poet, developed work from

In fact – as Cain’s sequence shows – what was being covered up was the original decision of Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield to open the exit gates at 2.47pm. One of his officers spoke to the inquiry: “I was quite shocked // It was totally unprecedented. // It was something you just didn’t do”. This was what caused the inflow of fans – “like sand into an egg timer”. Only at the second inquiry, did Duckenfield revise his earlier false statements: “I didn’t say, // ‘I have authorised the opening of the gates’”.

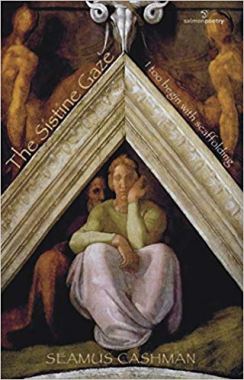

In fact – as Cain’s sequence shows – what was being covered up was the original decision of Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield to open the exit gates at 2.47pm. One of his officers spoke to the inquiry: “I was quite shocked // It was totally unprecedented. // It was something you just didn’t do”. This was what caused the inflow of fans – “like sand into an egg timer”. Only at the second inquiry, did Duckenfield revise his earlier false statements: “I didn’t say, // ‘I have authorised the opening of the gates’”.  David Pollard’s book is divided into three sections, one each on Parmigianino, Rembrandt and Caravaggio. Initially, Pollard presents a set of 15 self-declared “meditations” on a single work of art – Parmigianino’s ‘Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror’ (c. 1524). This is a bold move, given that John Ashbery did the same thing in 1974 and Pollard does explore ideas also found in Ashbery’s poem. Both writers are intrigued by a self-portrait painted onto a half-spherical, contoured surface to simulate a mirror such as was once used by barbers. The viewer gazes at an image of a mirror in which is reflected an image of the artist’s youthful and girlish face. It’s this sense of doubling images – an obvious questioning of what is real – that Pollard begins with. “You are a double-dealer” he declares, addressing the artist directly, though the language is quickly thickened and abstracted into a less than easy, philosophical, meditative style. It is the paradoxes that draw the poet: “you allow the doublings / inherent in your task to hide themselves / in open show, display art that / understands itself too well”. Indeed, this seems to be something of a definition of art for Pollard. “Let us be clear”, he says definitively, though the irony lies in the fact that such art asks questions about clarity precisely to destabilise it.

David Pollard’s book is divided into three sections, one each on Parmigianino, Rembrandt and Caravaggio. Initially, Pollard presents a set of 15 self-declared “meditations” on a single work of art – Parmigianino’s ‘Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror’ (c. 1524). This is a bold move, given that John Ashbery did the same thing in 1974 and Pollard does explore ideas also found in Ashbery’s poem. Both writers are intrigued by a self-portrait painted onto a half-spherical, contoured surface to simulate a mirror such as was once used by barbers. The viewer gazes at an image of a mirror in which is reflected an image of the artist’s youthful and girlish face. It’s this sense of doubling images – an obvious questioning of what is real – that Pollard begins with. “You are a double-dealer” he declares, addressing the artist directly, though the language is quickly thickened and abstracted into a less than easy, philosophical, meditative style. It is the paradoxes that draw the poet: “you allow the doublings / inherent in your task to hide themselves / in open show, display art that / understands itself too well”. Indeed, this seems to be something of a definition of art for Pollard. “Let us be clear”, he says definitively, though the irony lies in the fact that such art asks questions about clarity precisely to destabilise it. The 15 meditations are in free verse, the line endings often destabilising the sense, and they are lightly punctuated when I could have done with more conventional punctuation given the complex, involuted style. Pollard also likes to double up phrases, his second attempt often shifting ground or seeming propelled more by sound than sense. This is what the blurb calls Pollard’s “dense and febrile language” and it is fully self-conscious. In meditation 15, he observes that the artist’s paint is really “composed of almost nothing like words / that in their vanishings leave somewhat / of their meaning” – a ‘somewhat’ that falls well short of anything definitive. Of course, this again echoes Ashbery and appeals to our (post-)modern sensibility. Pollard images such a sense of loss with “a rustle of leaves among the winds / of autumn blowing in circles / back into seasons of the turning world”. He does not possess Ashbery’s originality of image, as here deploying the cliched autumnal leaves and then echoing Eliot’s “still point of the turning world”. Indeed, many poems are frequently allusive (particularly of Shakespearean phrases, Keats coming a close second) and for me this does not really work, the phrases striking as undigested shorthand for things that ought to be more freshly said.

The 15 meditations are in free verse, the line endings often destabilising the sense, and they are lightly punctuated when I could have done with more conventional punctuation given the complex, involuted style. Pollard also likes to double up phrases, his second attempt often shifting ground or seeming propelled more by sound than sense. This is what the blurb calls Pollard’s “dense and febrile language” and it is fully self-conscious. In meditation 15, he observes that the artist’s paint is really “composed of almost nothing like words / that in their vanishings leave somewhat / of their meaning” – a ‘somewhat’ that falls well short of anything definitive. Of course, this again echoes Ashbery and appeals to our (post-)modern sensibility. Pollard images such a sense of loss with “a rustle of leaves among the winds / of autumn blowing in circles / back into seasons of the turning world”. He does not possess Ashbery’s originality of image, as here deploying the cliched autumnal leaves and then echoing Eliot’s “still point of the turning world”. Indeed, many poems are frequently allusive (particularly of Shakespearean phrases, Keats coming a close second) and for me this does not really work, the phrases striking as undigested shorthand for things that ought to be more freshly said.

In fact, the woman is hardly given a voice and the substance of the sequence is dominated by the (male) artist’s reflections on his years-long task. He’s most often found “between this scaffold floor and ceiling”, complaining about his “craned neck”, pouring plaster, crushing pigments, enumerating at great length the qualities and shades of the paint he employs (Cashman risking an odd parody of a Dulux colour chart at times – “Variety is my clarity, / purity my colour power”). Later, we hear him complaining the plaster will not dry in the cold winter months. We even hear the artist reflecting on his own features, the famous “long white beard and beak-like nose”. These period and technical details work well, but Cashman’s Michelangelo sometimes also shades interestingly into a more future-aware voice, melding – I think – with the poet’s own voice. So he remarks: “Getting lost is not a condition men like me endure or venture on today. / All GPS and mobile interlinks enmesh our every step”. Later, a list of “everything there is” sweepingly includes “chair, man, woman; laptop or confession box”.

In fact, the woman is hardly given a voice and the substance of the sequence is dominated by the (male) artist’s reflections on his years-long task. He’s most often found “between this scaffold floor and ceiling”, complaining about his “craned neck”, pouring plaster, crushing pigments, enumerating at great length the qualities and shades of the paint he employs (Cashman risking an odd parody of a Dulux colour chart at times – “Variety is my clarity, / purity my colour power”). Later, we hear him complaining the plaster will not dry in the cold winter months. We even hear the artist reflecting on his own features, the famous “long white beard and beak-like nose”. These period and technical details work well, but Cashman’s Michelangelo sometimes also shades interestingly into a more future-aware voice, melding – I think – with the poet’s own voice. So he remarks: “Getting lost is not a condition men like me endure or venture on today. / All GPS and mobile interlinks enmesh our every step”. Later, a list of “everything there is” sweepingly includes “chair, man, woman; laptop or confession box”.

In a recent launch reading for her second collection, Dear Big Gods (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019), Mona Arshi suggested

In a recent launch reading for her second collection, Dear Big Gods (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019), Mona Arshi suggested As the blurb suggests, these poems are indeed “lyrical and exact exploration[s] of the aftershocks of grief”. But ‘Everywhere’ adopts a little more distance and develops the kind of floating and delicate lyricism that Arshi does so well. The absent brother/uncle is still alluded to: “We tell the children, we should not / look for him. He is everywhere”. As that final phrase suggests, the rawness of the grief is being transmuted into a sense of otherness, beyond the quotidian and material. It’s when Arshi takes her brother’s advice and lets go of “definitive knowledge” that her poems promise so much. ‘Little Prayer’ might be spoken by the dead or the living, left abandoned, but either way it argues a stoical resistance: “I am still here // hunkered down”. In a more conventional mode, ‘The Lilies’ develops the objective correlative of the flowers suffering from blight as an image of a spoliation that hurts and reminds, yet is allowed to persist: “I let them live on / beauty-drained / in their altar beds”.

As the blurb suggests, these poems are indeed “lyrical and exact exploration[s] of the aftershocks of grief”. But ‘Everywhere’ adopts a little more distance and develops the kind of floating and delicate lyricism that Arshi does so well. The absent brother/uncle is still alluded to: “We tell the children, we should not / look for him. He is everywhere”. As that final phrase suggests, the rawness of the grief is being transmuted into a sense of otherness, beyond the quotidian and material. It’s when Arshi takes her brother’s advice and lets go of “definitive knowledge” that her poems promise so much. ‘Little Prayer’ might be spoken by the dead or the living, left abandoned, but either way it argues a stoical resistance: “I am still here // hunkered down”. In a more conventional mode, ‘The Lilies’ develops the objective correlative of the flowers suffering from blight as an image of a spoliation that hurts and reminds, yet is allowed to persist: “I let them live on / beauty-drained / in their altar beds”.

Arshi’s continuing love affair with ghazals also seems to me to be an aspect of this same search for a form that holds both the connected and the stand-alone in a creative tension. ‘Ghazal: Darkness’ is very successful with the second line of each couplet returning to the refrain word, “darkness”, while the connective tissue of the poem allows a roaming through woods, soil, mushrooms and a mother’s praise of her daughters. Poems based on – or at least with the qualities of – dreams also stand out. The doctor in ‘Delivery Room’ asks the mother in the midst of her contractions, “Do you prefer the geometric or lyrical approach?” In ‘The Sisters’ the narrator dreams of “all the sisters I never had” and within 10 lines Arshi has expressed complex yearnings about loneliness and protectiveness in relation to siblings and self.

Arshi’s continuing love affair with ghazals also seems to me to be an aspect of this same search for a form that holds both the connected and the stand-alone in a creative tension. ‘Ghazal: Darkness’ is very successful with the second line of each couplet returning to the refrain word, “darkness”, while the connective tissue of the poem allows a roaming through woods, soil, mushrooms and a mother’s praise of her daughters. Poems based on – or at least with the qualities of – dreams also stand out. The doctor in ‘Delivery Room’ asks the mother in the midst of her contractions, “Do you prefer the geometric or lyrical approach?” In ‘The Sisters’ the narrator dreams of “all the sisters I never had” and within 10 lines Arshi has expressed complex yearnings about loneliness and protectiveness in relation to siblings and self. So, in ‘My Third Eye’, the narrator is “more perplexed than annoyed” that her own third eye – the mystical and esoteric belief in a speculative, spiritual perception – has not yet “opened”. The poem’s mode and tone is comic for the most part; there is a childish impatience in the voice, asking “Am I not as worthy as the buffalo, the ferryman, / the cook and the Dalit?”. But in the final lines, the holy man she visits is given more gravitas. He touches the narrator’s head “and with that my eyes suddenly watered, widened and / he sent me on my way as I was forever open open open”. The book also closes with the title poem, ‘Dear Big Gods’, which takes the form of a prayer: “all you have to do / is show yourself”, it pleads. The delicate probing of Arshi’s best poems, their stretching of perception and openness to unusual states of emotion are driven by this sort of spiritual quest. Personal tragedy has no doubt fed this creative drive but – as the poet seems to be aware – such grief is only an aspect of her vision and not the whole of it.

So, in ‘My Third Eye’, the narrator is “more perplexed than annoyed” that her own third eye – the mystical and esoteric belief in a speculative, spiritual perception – has not yet “opened”. The poem’s mode and tone is comic for the most part; there is a childish impatience in the voice, asking “Am I not as worthy as the buffalo, the ferryman, / the cook and the Dalit?”. But in the final lines, the holy man she visits is given more gravitas. He touches the narrator’s head “and with that my eyes suddenly watered, widened and / he sent me on my way as I was forever open open open”. The book also closes with the title poem, ‘Dear Big Gods’, which takes the form of a prayer: “all you have to do / is show yourself”, it pleads. The delicate probing of Arshi’s best poems, their stretching of perception and openness to unusual states of emotion are driven by this sort of spiritual quest. Personal tragedy has no doubt fed this creative drive but – as the poet seems to be aware – such grief is only an aspect of her vision and not the whole of it.

Lieke Marsman’s The Following Scan Will Last Five Minutes (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019) is an unlikely little gem of a book about cancer, language, poetry, Dutch politics, philosophy, the environment, the art of translation and friendship – all bound together by a burning desire (in both original author and her translator, Sophie Collins) to advocate the virtues of empathy. The PBS have chosen it as their Summer 2019 Recommended Translation.

Lieke Marsman’s The Following Scan Will Last Five Minutes (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019) is an unlikely little gem of a book about cancer, language, poetry, Dutch politics, philosophy, the environment, the art of translation and friendship – all bound together by a burning desire (in both original author and her translator, Sophie Collins) to advocate the virtues of empathy. The PBS have chosen it as their Summer 2019 Recommended Translation. The sort of silence Lorde fears is evoked in the monitory opening poem. Its unusual, impersonal narration is acutely aware of the lure of sinking away into the “morphinesweet unreality of the everyday”, of the allure of self-imposed isolation (“unplugg[ing] your router”) in the face of the diagnosis of disease. What the voice advises is the recognition that freedom consists not in denial, in being free of pain or need, but in being able to recognise our needs and satisfy them: “to be able to get up and go outside”. It’s this continuing self-awareness and the drive to try to achieve it that Marsman hopes for and (happily) comes to embody. But it was never going to be easy and towards the end of the poem sequence, these needs are honed to the bone:

The sort of silence Lorde fears is evoked in the monitory opening poem. Its unusual, impersonal narration is acutely aware of the lure of sinking away into the “morphinesweet unreality of the everyday”, of the allure of self-imposed isolation (“unplugg[ing] your router”) in the face of the diagnosis of disease. What the voice advises is the recognition that freedom consists not in denial, in being free of pain or need, but in being able to recognise our needs and satisfy them: “to be able to get up and go outside”. It’s this continuing self-awareness and the drive to try to achieve it that Marsman hopes for and (happily) comes to embody. But it was never going to be easy and towards the end of the poem sequence, these needs are honed to the bone:

Marsman tells us she read Audre Lorde and Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor after her operation and discharge from hospital. It’s Sontag who draws attention to the role of language in the way patients themselves and other people respond to cancer. Marsman asks herself: “Am I experiencing this cancer as an Actual Hell [. . .] or because that is the common perception of cancer?” The implied failure to achieve truly empathetic perception of the role and nature of the disease is echoed horribly in the empathetic failures and hypocrisies of Dutch politicians (UK readers will find this stuff all too familiar in our own politics). Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, blithely allocates billions of euros to multinationals like Shell and Unilever (on no valid basis) while overseeing cuts in health services. Marsman reads this as a failure to empathise with the ill. Another politician, Klaas Dijkhoff, reduces benefits on the basis that people encountering “bad luck” need to get themselves back on their own two feet. Bad luck here includes illness, disability, being born into poverty or abusive families, being compelled to flee your own country. Marsman’s own encounter with such ‘bad luck’ makes her rage all the more incandescent.

Marsman tells us she read Audre Lorde and Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor after her operation and discharge from hospital. It’s Sontag who draws attention to the role of language in the way patients themselves and other people respond to cancer. Marsman asks herself: “Am I experiencing this cancer as an Actual Hell [. . .] or because that is the common perception of cancer?” The implied failure to achieve truly empathetic perception of the role and nature of the disease is echoed horribly in the empathetic failures and hypocrisies of Dutch politicians (UK readers will find this stuff all too familiar in our own politics). Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, blithely allocates billions of euros to multinationals like Shell and Unilever (on no valid basis) while overseeing cuts in health services. Marsman reads this as a failure to empathise with the ill. Another politician, Klaas Dijkhoff, reduces benefits on the basis that people encountering “bad luck” need to get themselves back on their own two feet. Bad luck here includes illness, disability, being born into poverty or abusive families, being compelled to flee your own country. Marsman’s own encounter with such ‘bad luck’ makes her rage all the more incandescent.

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

In the summer of 2018, John Greening spent 2 weeks as artist-in-residence at the Heinrich Boll cottage in Dugort, Achill Island. The resulting

In the summer of 2018, John Greening spent 2 weeks as artist-in-residence at the Heinrich Boll cottage in Dugort, Achill Island. The resulting