It was a great pleasure recently to read for Poetry in Palmer’s Green with several other poets who have various sorts of north London connections: Kaye Lee, Briony Littlefair, Jeremy Page and Marvin Thompson. Kaye is planning her much-anticipated first collection; Jeremy edits The Frogmore Papers and his most recent book is Closing Time from Pindrop Press; Marvin has recently appeared to great acclaim in the Poetry School/Nine Arches book Primers II. Bryony’s first book publication is the 25 page chapbook, Giraffe, recently published by Seren Books, the contents of which formed the winning submission to the Mslexia Poetry Pamphlet Competition 2017. I’ve not seen it noticed enough in the reviews, so I thought I might try to say something about its considerable strengths. Littlefair also blogs here.

Giraffe, despite its weird title – which becomes clear only at the end of the collection – opens in familiar territory with a speedy, no-nonsense contemporary feel, using the title as part of the opening line: “‘Tara Miller’ // doesn’t have Facebook”. Her neglect of social media is one of Tara’s admired, unconventional aspects as the narrator recounts her (not so long past) school-days encounters with this girl. The narrator’s mother clearly feels Tara is not quite ‘our sort’ and in free verse lines of short, breathless colloquial phrases, the narrator paints a picture of the girl as a bit of a bully, as well as a little bit Byronic, being unpredictable and darkly “interesting”. Without really being aware of what her feelings are, the narrator is drawn to Tara, her “wavy, almost black” hair, her defiance in the face of boys, “her warm, / Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit breath on my neck”. This is a great double-portrait poem and sets up one of Littlefair’s recurrent themes, the tension between venture and routine.

Another young female narrator deliberately stays at home while her parents (conventionally) go to church on Sundays. She’s a teenage rebel without a cause as “The truth is I’m not sure what I did / those mornings”. The poem is built from a list (one of Littlefair’s favourite forms) of what she did and did not do. Littlefair is almost always good with her figurative language and here the girl is variously an undone shoelace, an open rucksack, a blunt knife. The urge to non-conformity outruns her imagination as to how she might spend her growing independence and there is an interesting tension at the last as her parents return, “whole” having “sung their hallelujahs” while the young girl is till restlessly revising her choice of nail polish, as yet unable to find what she’s after.

Another young female narrator deliberately stays at home while her parents (conventionally) go to church on Sundays. She’s a teenage rebel without a cause as “The truth is I’m not sure what I did / those mornings”. The poem is built from a list (one of Littlefair’s favourite forms) of what she did and did not do. Littlefair is almost always good with her figurative language and here the girl is variously an undone shoelace, an open rucksack, a blunt knife. The urge to non-conformity outruns her imagination as to how she might spend her growing independence and there is an interesting tension at the last as her parents return, “whole” having “sung their hallelujahs” while the young girl is till restlessly revising her choice of nail polish, as yet unable to find what she’s after.

The third poem in this very impressive opening to Giraffe is ‘Hallway’. Despite declaring at the outset “I can’t imagine how it must have been”, the young female narrator on this occasion does manage to achieve an insight into something ‘other’ than herself. What she can’t imagine at first is the impact of herself as a new-born on her young mother: “The constant interruptions, / the mess, the uncontrollable outpour of love / like a reflex, a weeping wound”. There follows a curious moment and a great simile. Imagining the years fast-forwarding, the world is compared to “scenery in a video game, pulling itself together / in front of me as I moved through it”. There’s an odd shift here, like a crashed synchromesh, in the switch from the mother’s point of view to the daughter’s but it does prepare for the second half of the poem which indeed is from the daughter’s perspective. The centrifugal, self-absorption of the child is broken at last on returning home from school early and finding her mother at the piano, “small / in her cardigan, eyes closed, somewhere else”. I’m not sure Littlefair’s image – comparing the child at this moment to a “just-plucked violin string” –is original enough for the circumstance, but the poem survives and the child’s expanded imaginative life is signalled as she stands “washed up in the hallway, wondering at her [mother’s] life”.

Another poem similarly explores a girl’s view of her Grandmother, wondering, in yet another list form, whether the older woman has had any sort of a life beyond the routines of socks and carrots and not gazing into mirrors. The solipsism of the young is a good subject and one Littlefair does well, but she’s as much interested in the other side of the coin: trying to imagine the lives of others. ‘Dear Anne Monroe, Healthcare Assistant’ does this, though the imaginative grain is a bit coarse perhaps. The Assistant’s life – beyond the present moment – is imagined as a mix of poor pay, weary commuting, casual racism and cheese and lettuce sandwiches. This is contrasted to her attention to her patients where she is steady, fierce, calls people sweetheart and is “magnificent”. The sentiment or feeling is right (not something anyone might disagree with) but the poem is sailing very close to caricature.

I think I find this with some other poems too, though it’s partly because Littlefair is admirably intent on presenting the working world, the world of labour, as routine in contrast to the allure of a more adventurous life. ‘Assignment brief’ presents itself as an old familiar’s introduction to a new girl’s routine office job; the lists and proffered options are funny but they slowly run out of steam. Likewise, the promisingly titled ‘Usually, I’m a different person at this party’ flags latterly. I’m imagining this as narrated by an older version of the girl who half fell in love with Tara Miller. Here, she shadow-boxes the risks of conventionality by over-insisting on her own sweeping and glamorous life, in the process claiming all sorts of ‘interesting’ aspects of herself: “I only ever have large and sweeping illnesses. / My lymph nodes swell glamorously. I never snuffle”. But the contrasts here are again rather roughly hewn and, in the end, close to cartoonish.

I think I find this with some other poems too, though it’s partly because Littlefair is admirably intent on presenting the working world, the world of labour, as routine in contrast to the allure of a more adventurous life. ‘Assignment brief’ presents itself as an old familiar’s introduction to a new girl’s routine office job; the lists and proffered options are funny but they slowly run out of steam. Likewise, the promisingly titled ‘Usually, I’m a different person at this party’ flags latterly. I’m imagining this as narrated by an older version of the girl who half fell in love with Tara Miller. Here, she shadow-boxes the risks of conventionality by over-insisting on her own sweeping and glamorous life, in the process claiming all sorts of ‘interesting’ aspects of herself: “I only ever have large and sweeping illnesses. / My lymph nodes swell glamorously. I never snuffle”. But the contrasts here are again rather roughly hewn and, in the end, close to cartoonish.

A far more original poem is ‘Maybe this is why women get to live longer’ in which a man-splaining man dominates a watched conversation, the woman “holding her face in different positions / to signify reaction: empathy, humour, gentle and agreeable surprise”. This is acutely observed and the point is well made in the serious-surreal twist of the rhetorical question, “Is there a place / the time goes that women have been / listening to men?” Even better is the imaginative act of the details of the woman now left alone, returned to the “cool clean shirt / of herself”. A really effective line break there, followed by the naturalistic details of her leaving the bathroom door open “as she wees”, then the more disturbing one of her pinching “the skin on her forearm – lightly, / and then harder”. I guess she’s pinching herself awake after the soporific conversational style of the man, but more disturbingly she may be harming herself as a symptom of deeper psychological troubles.

The latter view is more than a possibility given that Littlefair’s poems also boldly explore the self’s relation with itself. The encounter between self and future self is plainly and humorously told in ‘Visitations from future self’ and it finds the present self in trouble, pleading “I can’t go on / like this, my life a tap that won’t / switch on”. Here, the present self’s cliched and optimistic hopes for a “rain-before-the-rainbow thing” are denigrated and stared down by the future self. ‘Sertraline’ echoes Plath’s The Bell Jar in its evocation of a summer spent on an anti-depressive drug. And ‘Giraffe’ itself is a prose poem (there are 3 prose pieces in the whole book) in which a voice is offering reassurances to someone hoping to “feel better”. In a final list, images of a return to ‘health’ are offered. Particularly good is the idea that suffering will remain a fact but “your sadness will be graspable, roadworthy, have handlebars”. And lastly, “When you feel better, you will not always be happy, but when happiness does come, it will be long-legged, sun-dappled: a giraffe.”

The latter view is more than a possibility given that Littlefair’s poems also boldly explore the self’s relation with itself. The encounter between self and future self is plainly and humorously told in ‘Visitations from future self’ and it finds the present self in trouble, pleading “I can’t go on / like this, my life a tap that won’t / switch on”. Here, the present self’s cliched and optimistic hopes for a “rain-before-the-rainbow thing” are denigrated and stared down by the future self. ‘Sertraline’ echoes Plath’s The Bell Jar in its evocation of a summer spent on an anti-depressive drug. And ‘Giraffe’ itself is a prose poem (there are 3 prose pieces in the whole book) in which a voice is offering reassurances to someone hoping to “feel better”. In a final list, images of a return to ‘health’ are offered. Particularly good is the idea that suffering will remain a fact but “your sadness will be graspable, roadworthy, have handlebars”. And lastly, “When you feel better, you will not always be happy, but when happiness does come, it will be long-legged, sun-dappled: a giraffe.”

The designation ‘a young poet to watch’ is over-used but on this occasion it needs to be said loudly. Giraffe contains a number of fresh, intriguing and fully-achieved poems. It’s well worth seeking out. I well remember reading and being very impressed by Liz Berry’s 2010 Tall Lighthouse debut chapbook, the patron saint of schoolgirls, and this selection from Bryony Littlefair’s early work runs it close. My review of Liz Berry’s subsequent, prize-winning full collection, Black Country, can be read here.

The designation ‘a young poet to watch’ is over-used but on this occasion it needs to be said loudly. Giraffe contains a number of fresh, intriguing and fully-achieved poems. It’s well worth seeking out. I well remember reading and being very impressed by Liz Berry’s 2010 Tall Lighthouse debut chapbook, the patron saint of schoolgirls, and this selection from Bryony Littlefair’s early work runs it close. My review of Liz Berry’s subsequent, prize-winning full collection, Black Country, can be read here.

![flowermoonPNG[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/flowermoonpng1.png?w=437&h=291)

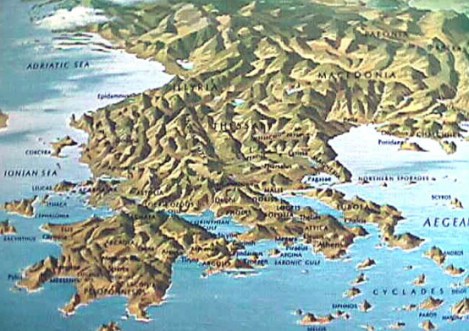

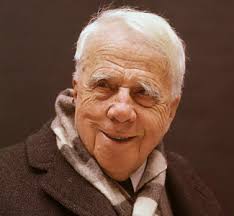

Frost wants to make big claims for metaphorical thinking: “I have wanted in late years to go further and further in making metaphor the whole of thinking”. He allows the exception of “mathematical thinking” but wants all other knowledge, including “scientific thinking” to be brought within the bounds of metaphor. He suggests the Greeks’ foundational thought about the world, the “All”, was fundamentally metaphorical in nature, especially Pythagoras’ concept of the nature of things as comparable to number: “Number of what? Number of feet, pounds and seconds”. This is the basis for a scientific, empirical (measurable) view of the world and hence “has held and held” in the shape of our still-predominating scientific view of it.

Frost wants to make big claims for metaphorical thinking: “I have wanted in late years to go further and further in making metaphor the whole of thinking”. He allows the exception of “mathematical thinking” but wants all other knowledge, including “scientific thinking” to be brought within the bounds of metaphor. He suggests the Greeks’ foundational thought about the world, the “All”, was fundamentally metaphorical in nature, especially Pythagoras’ concept of the nature of things as comparable to number: “Number of what? Number of feet, pounds and seconds”. This is the basis for a scientific, empirical (measurable) view of the world and hence “has held and held” in the shape of our still-predominating scientific view of it.

That we have a tendency to forget this provisional nature of knowledge and understanding seems to be Frost’s next point. We take up arms (as it were) by taking up certain metaphorical ideas and making totems of them. He berates Freudianism’s focus on “mental health” as an example of how “the devil can quote Scripture, which simply means that the good words you have lying around the devil can use for his purposes as well as anybody else”. That this is dangerous (makes us not safe) is illustrated by the passage of dialogue Frost now gives between himself and somebody else. The other argues that the universe is like a machine but Frost (adopting a sort of Socratic interrogation technique) draws out the limits of the metaphor, concluding he “wanted to go just that far with that metaphor and no further. And so do we all. All metaphor breaks down somewhere. That is the beauty of it. It is touch and go with the metaphor, and until you have lived with it long enough you don’t know when it is going. You don’t know how much you can get out of it and when it will cease to yield. It is a very living thing. It is as life itself”.

That we have a tendency to forget this provisional nature of knowledge and understanding seems to be Frost’s next point. We take up arms (as it were) by taking up certain metaphorical ideas and making totems of them. He berates Freudianism’s focus on “mental health” as an example of how “the devil can quote Scripture, which simply means that the good words you have lying around the devil can use for his purposes as well as anybody else”. That this is dangerous (makes us not safe) is illustrated by the passage of dialogue Frost now gives between himself and somebody else. The other argues that the universe is like a machine but Frost (adopting a sort of Socratic interrogation technique) draws out the limits of the metaphor, concluding he “wanted to go just that far with that metaphor and no further. And so do we all. All metaphor breaks down somewhere. That is the beauty of it. It is touch and go with the metaphor, and until you have lived with it long enough you don’t know when it is going. You don’t know how much you can get out of it and when it will cease to yield. It is a very living thing. It is as life itself”.

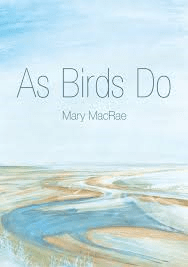

It may be that this ability to be sustained by scraps and glimpses, the sense that the self is most fully resolved in a lack of egotism, in its encounter with ordinary things, can diminish some of the sting of mortality. In a poem like ‘White’, MacRae manages to celebrate again the ordinariness of familiar things while at the same time sustaining a contentedness (or at least an absence of fear) at the prospect of the self’s vanishing: “You can disappear in a house where / you feel at home; the rooms are spaces / for day-dreams, maps of an interior / turned inside out”. Rather than Macbeth, it is Hamlet’s resolve to “let be” that comes to mind as this calm, accessible, colourful and wonderfully dignified poem concludes:

It may be that this ability to be sustained by scraps and glimpses, the sense that the self is most fully resolved in a lack of egotism, in its encounter with ordinary things, can diminish some of the sting of mortality. In a poem like ‘White’, MacRae manages to celebrate again the ordinariness of familiar things while at the same time sustaining a contentedness (or at least an absence of fear) at the prospect of the self’s vanishing: “You can disappear in a house where / you feel at home; the rooms are spaces / for day-dreams, maps of an interior / turned inside out”. Rather than Macbeth, it is Hamlet’s resolve to “let be” that comes to mind as this calm, accessible, colourful and wonderfully dignified poem concludes: For MacRae’s interest in and skill with poetic form, we need look no further than the extraordinary glose on a quatrain from Alice Oswald (the earlier collection contained another on lines from Mary Oliver). For most poets, this form is little more than an exhibitionist high-wire act, but MacRae’s poems are moving and complete. Her use of poetic form here, particularly in some of these last poems, reminds me of Tony Harrison’s conviction that its containment “is like a life-support system. It means I feel I can go closer to the fire, deeper into the darkness . . . I know I have this rhythm to carry me to the other side” (Tony Harrison: Critical Anthology, ed. Astley, Bloodaxe Books, 1991, p.43). Appropriately, in ‘Jar’, she contemplates with admiration an object that has “gone through fire, / risen from ashes and bone-shards / to float, nameless, into our air”. Here, the narrator movingly lays aside the wary scepticism of the Thomas epigraph and rests her cheek on the jar’s warmth to “feel its gravity-pull / as if it proved the afterlife of things”.

For MacRae’s interest in and skill with poetic form, we need look no further than the extraordinary glose on a quatrain from Alice Oswald (the earlier collection contained another on lines from Mary Oliver). For most poets, this form is little more than an exhibitionist high-wire act, but MacRae’s poems are moving and complete. Her use of poetic form here, particularly in some of these last poems, reminds me of Tony Harrison’s conviction that its containment “is like a life-support system. It means I feel I can go closer to the fire, deeper into the darkness . . . I know I have this rhythm to carry me to the other side” (Tony Harrison: Critical Anthology, ed. Astley, Bloodaxe Books, 1991, p.43). Appropriately, in ‘Jar’, she contemplates with admiration an object that has “gone through fire, / risen from ashes and bone-shards / to float, nameless, into our air”. Here, the narrator movingly lays aside the wary scepticism of the Thomas epigraph and rests her cheek on the jar’s warmth to “feel its gravity-pull / as if it proved the afterlife of things”.

*As a labouring translator myself, I have long remembered Grigson’s brilliant put-down in his Introduction to the Faber Book of Love Poems (1973). Explaining why he has not included any translations at all, he declares that their “unmeasured, thin-rolled short crust” would prove detrimental to the health of the nation’s poetic taste. Times have changed, thank goodness.

*As a labouring translator myself, I have long remembered Grigson’s brilliant put-down in his Introduction to the Faber Book of Love Poems (1973). Explaining why he has not included any translations at all, he declares that their “unmeasured, thin-rolled short crust” would prove detrimental to the health of the nation’s poetic taste. Times have changed, thank goodness.

.

.

![1074-Poetry-Review_Cover-RGB-300-w-shadow-429x600[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1074-poetry-review_cover-rgb-300-w-shadow-429x6001.jpg?w=199&h=279)

![jellyfish[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jellyfish1.jpg?w=700)

![alpine-skiing-877410_640[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/alpine-skiing-877410_6401.jpg?w=348&h=261)

![DKKnm3zX0AAbJg_[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/dkknm3zx0aabjg_1.jpg?w=360&h=385)

![Lee-Miller[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/lee-miller1.jpg?w=276&h=368)

![Collaborators[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/collaborators1.jpg?w=366&h=245)

![486434472_f02117992d_o[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/486434472_f02117992d_o1.jpg?w=247&h=288)

![Saphra-interview[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/saphra-interview1.jpg?w=700)

![lee_miller_biography_beautiful_young_thing_audacious_muse_photographer_3l[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/lee_miller_biography_beautiful_young_thing_audacious_muse_photographer_3l1.jpg?w=573&h=322)