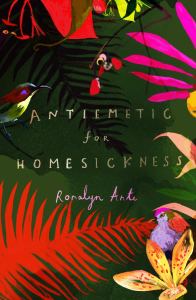

Romalyn Ante was born in Lipa Batangas, in the Philippines, in 1989. For much of her childhood her parents were absent as migrant workers and the family moved to the UK in the mid-2000s where her mother was a nurse in the NHS. Ante herself now also works as a registered nurse and psychotherapist. As a result, this debut collection has multiple perspectives running through it: the child grappling with the parents’ absence, the mother’s exile, the daughter’s later emigration and a broader, political sense of the plight of migrant workers. The economic driving force behind such movements of people is recorded in ‘Mateo’, responding to the Gospel of Matthew’s observation about birds neither sowing nor reaping with this downright response: “But birds have no bills”. So, in poem after poem, the need for money, for a roof, livestock, fruit trees, medical treatment, even for grave plots back home is made evident.

Romalyn Ante was born in Lipa Batangas, in the Philippines, in 1989. For much of her childhood her parents were absent as migrant workers and the family moved to the UK in the mid-2000s where her mother was a nurse in the NHS. Ante herself now also works as a registered nurse and psychotherapist. As a result, this debut collection has multiple perspectives running through it: the child grappling with the parents’ absence, the mother’s exile, the daughter’s later emigration and a broader, political sense of the plight of migrant workers. The economic driving force behind such movements of people is recorded in ‘Mateo’, responding to the Gospel of Matthew’s observation about birds neither sowing nor reaping with this downright response: “But birds have no bills”. So, in poem after poem, the need for money, for a roof, livestock, fruit trees, medical treatment, even for grave plots back home is made evident.

Antiemetic for Homesickness also consequently has two prime locations: the UK appears as snow-bound streets, red buses, the day to day labour of nursing grateful (and often less than grateful) patients, casual racism. But it is the home country that predominates in vivid images of its landscape, people, culture, folk tales, food and frequent fragments of its Tagalog language (there is a glossary of sorts, but I found many phrases not included). So the promise implied by the title poem – a cure for homesickness – is willed, even a delusion, but a necessary one adopted for self-preservation. It’s a great poem. Opening with “A day will come when you won’t miss / the country na nagluwal sa ‘yo” (lit. who gave birth to you), it also closes in the same mood: “You will learn to heal the wounds / of [patients’] lives and the wounds of yours”. But the central stanzas are densely populated by memories of home, the airport goodbyes, the tapes recorded by left-behind children, the recalled intimacies of the left-behind husband, the gatherings and food of the distant place. The antiemetic is proving less than effective.

This is the material for all Ante’s poems here. ‘The Making of a Smuggler’ opens with “Wherever we travel, we carry / the whole country with us” – lines that recall Moniza Alvi’s, ‘The country at my shoulder’ from 1993. Despite Ante’s personal experiences, these poems often speak in this plural pronoun (a sense of solidarity in experiences shared plus a pained awareness of the plight of unnumbered, unknown migrant workers). The ‘smuggling’ image also suggests an illicit action, a coming under suspicion in the destination country. What is being smuggled across borders under the insensitive noses of its guardians are memories, places: “He can’t cup his ear // with my palm and hear the surfs / of Siargao beach”. If these are thoughts on arrival then ‘Notes inside a Balikbayan Box’ evoke the on-going sense of loss, distance, almost bereavement accumulating through years of working abroad. Such boxes – Ante’s notes explain – are used by Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) and filled with small gifts to be eventually sent back home, a kind of ‘repatriate box’.

This is the material for all Ante’s poems here. ‘The Making of a Smuggler’ opens with “Wherever we travel, we carry / the whole country with us” – lines that recall Moniza Alvi’s, ‘The country at my shoulder’ from 1993. Despite Ante’s personal experiences, these poems often speak in this plural pronoun (a sense of solidarity in experiences shared plus a pained awareness of the plight of unnumbered, unknown migrant workers). The ‘smuggling’ image also suggests an illicit action, a coming under suspicion in the destination country. What is being smuggled across borders under the insensitive noses of its guardians are memories, places: “He can’t cup his ear // with my palm and hear the surfs / of Siargao beach”. If these are thoughts on arrival then ‘Notes inside a Balikbayan Box’ evoke the on-going sense of loss, distance, almost bereavement accumulating through years of working abroad. Such boxes – Ante’s notes explain – are used by Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) and filled with small gifts to be eventually sent back home, a kind of ‘repatriate box’.

Accordingly, the poem takes the form of a note – “Dear son” – partly accompanying objects such as shoes, video tapes, E45 cream, incontinence pads, perfume but, just as important, offering life-advice and apologies:

I owe you for every Simbang Gabi and PTA meeting

I could not attend. I promise I’ll be there for Christmas.

I know I’ve been saying this for a decade now.

Scattered throughout the collection are short extracts intended to reflect cassette tape recordings – sent in the reverse direction to the Balikbayan Box – by a child to her distant mother. The risks of attempting such a child’s perspective are many and Ante keeps these little more than fragmentary utterances, not authentically child-like. These were some of the less successful moments in the collection, many others of which also arose from such formal experiments. Ante tries out the forms of a drug protocol, a questionnaire, a concrete poem, centred, right or left justified verse, prose passages, assemblages of fragments, typographical variants. Such moments presumably constitute the “dazzling formal dexterity” alluded to in the jacket blurb, but you’d not read Ante for this but for the poems’ “emotional resonance”, also referred to in the blurb.

The plurality of her subjects also gives rise to poems in several voices. ‘Tagay!’ portrays the migrant workers’ embattled situation and their making the best of it through the communal drinking of Lambanog (distilled palm liquor) – the title is something akin to ‘Cheers!’ Each speaker toasts the others present, going on to imagine their personal homecoming: welcoming smiles at Arrivals, the bringing home of Cadbury’s chocolate, the heat of Manila, home-cooked food at last, story-telling, marital sex. Many of the speakers cannot keep their work out of the moment: “Tomorrow we’ll be changing bed covers, / soaking dentures, creaming cracked heels”… but for the moment, “Tagay!” Something similar is attempted in ‘Group Portrait at the Stopover’, in which migrant workers are briefly thrown together at an airport, in 5 short sections swapping gifts and stories of their labours and abuse, preferring not to think “of the next generation that will meet at this gate, / the same old stories that will hum out of younger mouths”.

‘Group Portrait..’ is one of Ante’s poems that explicitly addresses the long-standing global reality of migrant labour and ‘Invisible Women’ does the same. These are the women, world over, who are seldom given credit or even attention, yet are “goddesses of caring and tending”. Ante’s mother is one of them, a woman who “walks to work when the sky is black / and comes out from work when the sky is black” (the studied repetitions here more effective than many other formal innovations). The deification of such women is part of Ante’s point. The costs of such migration are repeatedly made clear in this book, but the admiration for those who leave home to earn money for the benefit of those left at home is also clear. These invisible women (and as often men) are heroic in their determination, their sacrifices and their hard work.

A poem that returns the reader to the individual is ‘Ode to a Pot Noodle’. Owing something to Neruda’s Odas elementales (1954), the narrator is taking a short break from “fast-paced” hospital duties – a Pot Noodle is all there is time for. In the daze of night and fatigue, images arise (of course) of her distant home, her grandfather, of Philippine food and conversations that, in the time it takes to boil a kettle, vanish as quickly. She addresses those distant people: “this should have been an ode to you. / Forgive me, forgive me”. But the Ode has already been written in the course of Antiemetic for Homesickness. The collection is a testament to the presence of the absent, the persistence of memory, the heroism and suffering of those who we hold at arms’ length, invisible but without whom our modern society – our NHS – would fail to function. In the time of Covid – and after it too – Romalyn Ante’s book is reminding us of debts and inequalities too long unacknowledged.

A poem that returns the reader to the individual is ‘Ode to a Pot Noodle’. Owing something to Neruda’s Odas elementales (1954), the narrator is taking a short break from “fast-paced” hospital duties – a Pot Noodle is all there is time for. In the daze of night and fatigue, images arise (of course) of her distant home, her grandfather, of Philippine food and conversations that, in the time it takes to boil a kettle, vanish as quickly. She addresses those distant people: “this should have been an ode to you. / Forgive me, forgive me”. But the Ode has already been written in the course of Antiemetic for Homesickness. The collection is a testament to the presence of the absent, the persistence of memory, the heroism and suffering of those who we hold at arms’ length, invisible but without whom our modern society – our NHS – would fail to function. In the time of Covid – and after it too – Romalyn Ante’s book is reminding us of debts and inequalities too long unacknowledged.

Nina Mingya Powles’ collection, Magnolia 木蘭, is an uneven book of great energy, of striking originality, but also of a great deal of borrowing. This is what good debut collections used to be like! I’m reminded of Glyn Maxwell’s disarming observation in On Poetry (Oberon Books, 2012) that he “had absolutely nothing to say till [he] was about thirty-four”. The originality of Magnolia 木蘭 is largely derived from Powles’ background and brief biographical journey. She is of mixed Malaysian-Chinese heritage, born and raised in New Zealand, spending a couple of years as a student in Shanghai and now living in the UK. Her subjects are language/s, exile and displacement, cultural loss/assimilation and identity. Shanghai is the setting for most of the poems here and behind them all loiter the shadows and models of

Nina Mingya Powles’ collection, Magnolia 木蘭, is an uneven book of great energy, of striking originality, but also of a great deal of borrowing. This is what good debut collections used to be like! I’m reminded of Glyn Maxwell’s disarming observation in On Poetry (Oberon Books, 2012) that he “had absolutely nothing to say till [he] was about thirty-four”. The originality of Magnolia 木蘭 is largely derived from Powles’ background and brief biographical journey. She is of mixed Malaysian-Chinese heritage, born and raised in New Zealand, spending a couple of years as a student in Shanghai and now living in the UK. Her subjects are language/s, exile and displacement, cultural loss/assimilation and identity. Shanghai is the setting for most of the poems here and behind them all loiter the shadows and models of

I don’t think the intriguing glimpses of an individual young woman in this first poem are much developed in later ones. The Mulan figure makes a couple of other appearances in the book and is reprised in the concluding poem, ‘Magnolia, jade orchid, she-wolf’. This consists of even shorter prose observations. In Chinese, ‘mulan’ means magnolia so the fragments here cover the plant family Magnoliaceae, the film again, the Chinese characters for mulan, Shanghai moments, school days back in New Zealand and Adeline Yen Mah’s Chinese Cinderella. It’s hard not to think you are reading much the same poem, using similar techniques, though this one ends more strongly: “My mouth a river in full bloom”.

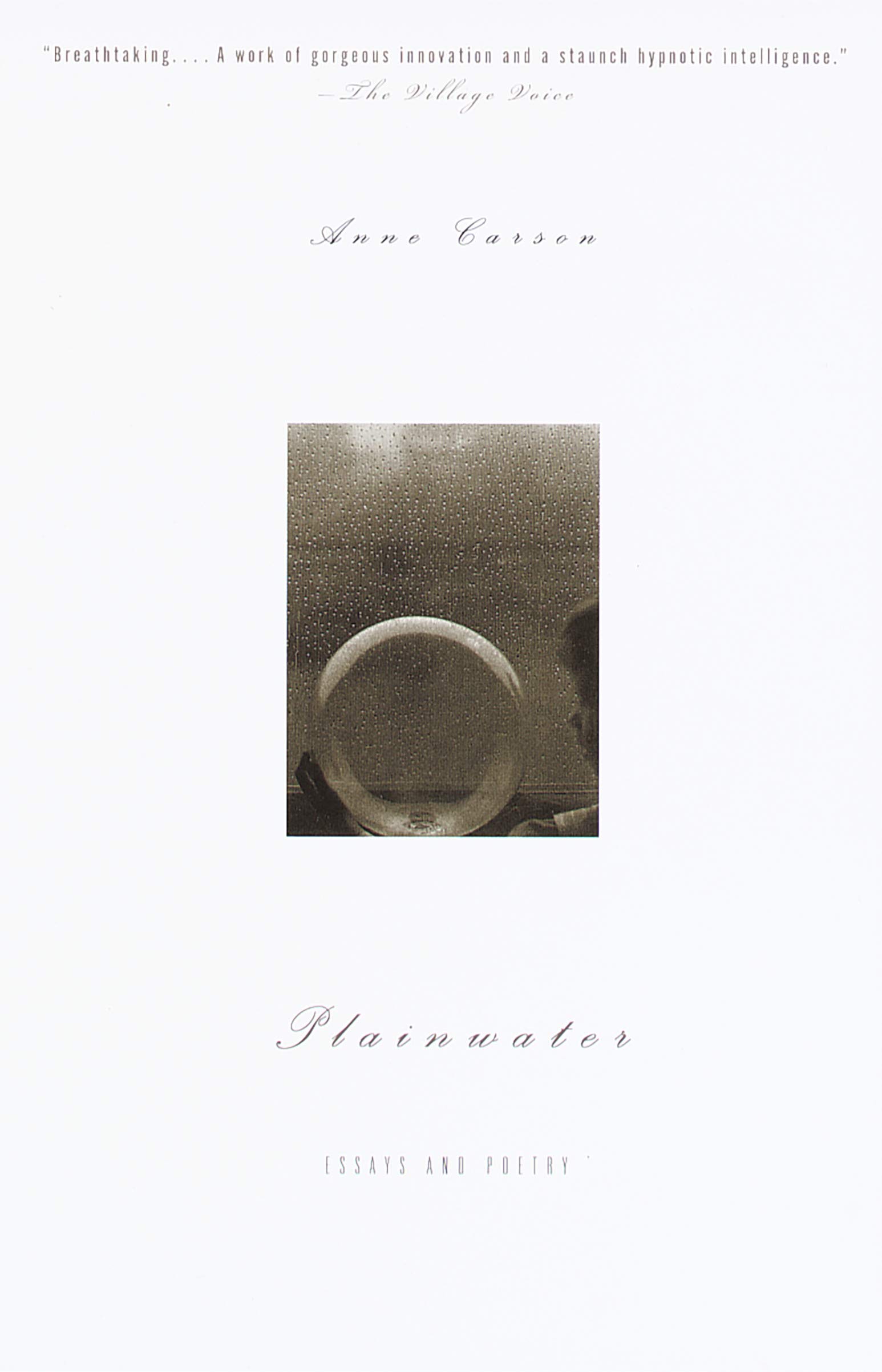

I don’t think the intriguing glimpses of an individual young woman in this first poem are much developed in later ones. The Mulan figure makes a couple of other appearances in the book and is reprised in the concluding poem, ‘Magnolia, jade orchid, she-wolf’. This consists of even shorter prose observations. In Chinese, ‘mulan’ means magnolia so the fragments here cover the plant family Magnoliaceae, the film again, the Chinese characters for mulan, Shanghai moments, school days back in New Zealand and Adeline Yen Mah’s Chinese Cinderella. It’s hard not to think you are reading much the same poem, using similar techniques, though this one ends more strongly: “My mouth a river in full bloom”. Unlike Carson’s use of fragmentary texts, Powles is less convincing and often gives the impression of casting around for links. This is intended to reflect a sense of rootlessness (cultural, racial, personal) but there is a willed quality to the composition. One of the things Powles does have to say (thinking again of Maxwell’s observation) is the doubting of what is dream and what is real. The prose piece, ‘Miyazaki bloom’, opens with this idea and the narrator’s sense of belonging “nowhere” is repeated. This is undoubtedly heartfelt – though students living in strange cities have often felt the same way. Powles also casts around for role models (beyond Mulan) and writes about the New Zealand poet, Robin Hyde and the great Chinese author Eileen Chang, both of whom resided in Shanghai for a time. ‘Falling City’ is a rather exhausting 32 section prose exploration of Chang’s residence, mixing academic observations, personal reminiscence and moments of fantasy to end (bathetically) with inspiration for Powles: “I sit down at one of the café tables and begin to write. It is the first day of spring”.

Unlike Carson’s use of fragmentary texts, Powles is less convincing and often gives the impression of casting around for links. This is intended to reflect a sense of rootlessness (cultural, racial, personal) but there is a willed quality to the composition. One of the things Powles does have to say (thinking again of Maxwell’s observation) is the doubting of what is dream and what is real. The prose piece, ‘Miyazaki bloom’, opens with this idea and the narrator’s sense of belonging “nowhere” is repeated. This is undoubtedly heartfelt – though students living in strange cities have often felt the same way. Powles also casts around for role models (beyond Mulan) and writes about the New Zealand poet, Robin Hyde and the great Chinese author Eileen Chang, both of whom resided in Shanghai for a time. ‘Falling City’ is a rather exhausting 32 section prose exploration of Chang’s residence, mixing academic observations, personal reminiscence and moments of fantasy to end (bathetically) with inspiration for Powles: “I sit down at one of the café tables and begin to write. It is the first day of spring”.

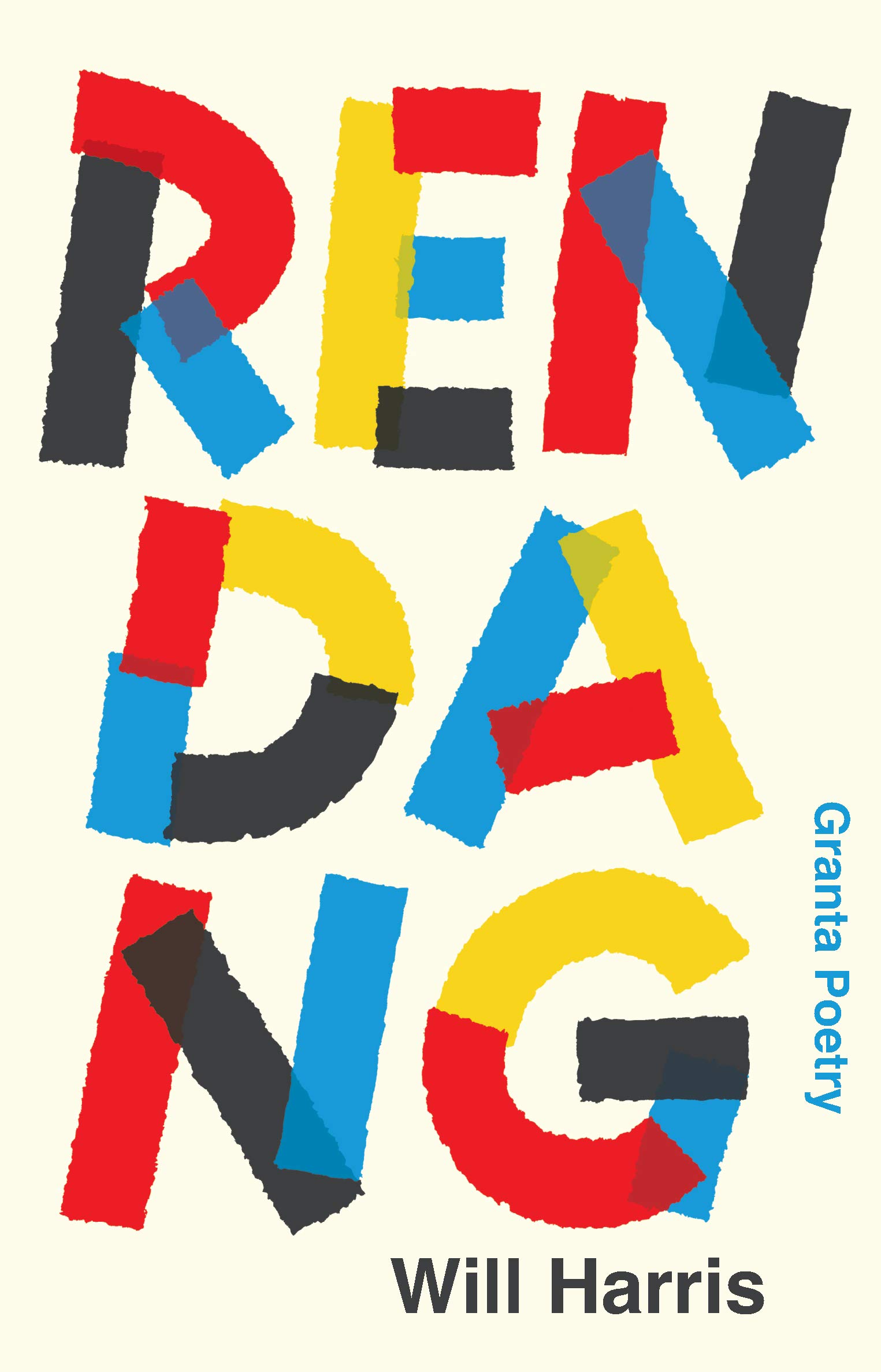

At the heart of Will Harris’ first collection is the near pun between ‘rendang’ and ‘rending’. The first term is a spicy meat dish, originating from West Sumatra, the country of Harris’ paternal grandmother, a dish traditionally served at ceremonial occasions to honour guests. In one of many self-reflexive moments, Harris imagines talking to the pages of his own book, saying “RENDANG”, but their response is, “No, no”. The dish perhaps represents a cultural and familial connectiveness that has long since been severed, subject to a process of rending, and the best poems here take this deracinated state as a given. They are voiced by a young, Anglo-Indonesian man, living in London and though there is a strong undertow of loss and distance, through techniques such as counterpoint, cataloguing and compilation, the impact of the book, if not exactly of sweetness, is of human contact and discourse, of warmth, of “something new” being made.

At the heart of Will Harris’ first collection is the near pun between ‘rendang’ and ‘rending’. The first term is a spicy meat dish, originating from West Sumatra, the country of Harris’ paternal grandmother, a dish traditionally served at ceremonial occasions to honour guests. In one of many self-reflexive moments, Harris imagines talking to the pages of his own book, saying “RENDANG”, but their response is, “No, no”. The dish perhaps represents a cultural and familial connectiveness that has long since been severed, subject to a process of rending, and the best poems here take this deracinated state as a given. They are voiced by a young, Anglo-Indonesian man, living in London and though there is a strong undertow of loss and distance, through techniques such as counterpoint, cataloguing and compilation, the impact of the book, if not exactly of sweetness, is of human contact and discourse, of warmth, of “something new” being made. This last phrase comes from ‘State-Building’, one of the more interesting, earlier poems in Rendang (a book which feels curiously hesitant and experimental in its first 42 pages, then bursts into full voice from its third section onwards). This poem characteristically draws very diverse topics together, starting from Derek Walcott’s observations on love (his image is of a broken vase which is all the stronger for having been reassembled). This thought leads to seeing a black figure vase in the British Museum which takes the poem (in a Keatsian moment, imagining what’s not represented there) to thoughts of “freeborn” men debating philosophy and propolis, or bee glue, metaphorically something that has to come “before – is crucial for – the building of a state”. The bees lead the narrator’s fluent thoughts to a humming bin bag, then a passing stranger who reminds the narrator of his grandmother and the familial connection takes him to his own father, at work repairing a vase, a process (like the poem we have just read) of assemblage using literal and metaphorical “putty, spit, glue” to bring forth, not sweetness, but in a slightly cloying rhyme, that “something new”.

This last phrase comes from ‘State-Building’, one of the more interesting, earlier poems in Rendang (a book which feels curiously hesitant and experimental in its first 42 pages, then bursts into full voice from its third section onwards). This poem characteristically draws very diverse topics together, starting from Derek Walcott’s observations on love (his image is of a broken vase which is all the stronger for having been reassembled). This thought leads to seeing a black figure vase in the British Museum which takes the poem (in a Keatsian moment, imagining what’s not represented there) to thoughts of “freeborn” men debating philosophy and propolis, or bee glue, metaphorically something that has to come “before – is crucial for – the building of a state”. The bees lead the narrator’s fluent thoughts to a humming bin bag, then a passing stranger who reminds the narrator of his grandmother and the familial connection takes him to his own father, at work repairing a vase, a process (like the poem we have just read) of assemblage using literal and metaphorical “putty, spit, glue” to bring forth, not sweetness, but in a slightly cloying rhyme, that “something new”.

I

I

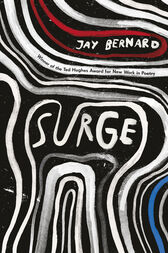

But Surge itself has since gone through various forms. There were 10 original poems written quickly in 2016. There was a performance piece (at London’s Roundhouse) in the summer of 2017 (it was this version that won the Ted Hughes Award for New Work in poetry in 2017). But it has taken 3 years for this Chatto book to be finalised. In an interview just last year, Bernard observed that they were still unclear what the “final structure” of the material would be. I’m possessed of no insider knowledge on this, but it looks as if this “final” version took some considerable effort – reading it makes me conscious of the strait-jacket that a conventional slim volume of poetry imposes – and I’m not sure the finalised 50-odd pages of the collection really act as the best foil for what are, without doubt, a series of stunningly powerful poems. The blurb and publicity present the book (as publishers so often do) as wholly focused on the New Cross and Grenfell fires but this isn’t really true and something is lost in including the more miscellaneous pieces, particularly towards the end of the book.

But Surge itself has since gone through various forms. There were 10 original poems written quickly in 2016. There was a performance piece (at London’s Roundhouse) in the summer of 2017 (it was this version that won the Ted Hughes Award for New Work in poetry in 2017). But it has taken 3 years for this Chatto book to be finalised. In an interview just last year, Bernard observed that they were still unclear what the “final structure” of the material would be. I’m possessed of no insider knowledge on this, but it looks as if this “final” version took some considerable effort – reading it makes me conscious of the strait-jacket that a conventional slim volume of poetry imposes – and I’m not sure the finalised 50-odd pages of the collection really act as the best foil for what are, without doubt, a series of stunningly powerful poems. The blurb and publicity present the book (as publishers so often do) as wholly focused on the New Cross and Grenfell fires but this isn’t really true and something is lost in including the more miscellaneous pieces, particularly towards the end of the book. Bernard’s poetic voice is at its best when making full use of the licence of free forms, broken grammar, infrequent punctuation, the colloquial voice and often incantatory patois. So a voice in ‘Harbour’ wanders across the page, hesitantly, uncertainly, till images of heat, choking and breaking glass make it clear this is someone caught in the New Cross Fire. Another voice in ‘Clearing’ watches, in the aftermath of the blaze, as an officer collect body parts (including the voice’s own body): “from the bag I watch his face turn away”. The cryptically titled ‘+’ and ‘–’ shift to broken, dialogic prose as a father is asked to identify his dead son through the clothes he was wearing. Then the son’s voice cries out for and watches his father come to the morgue to identify his body. This skilful voice throwing is a vivid way of portraying a variety of individuals and their grief. ‘Kitchen’ offers a calmer voice re-visiting her mother’s house, the details and familiarity evoking simple things that have been lost in the death of the child:

Bernard’s poetic voice is at its best when making full use of the licence of free forms, broken grammar, infrequent punctuation, the colloquial voice and often incantatory patois. So a voice in ‘Harbour’ wanders across the page, hesitantly, uncertainly, till images of heat, choking and breaking glass make it clear this is someone caught in the New Cross Fire. Another voice in ‘Clearing’ watches, in the aftermath of the blaze, as an officer collect body parts (including the voice’s own body): “from the bag I watch his face turn away”. The cryptically titled ‘+’ and ‘–’ shift to broken, dialogic prose as a father is asked to identify his dead son through the clothes he was wearing. Then the son’s voice cries out for and watches his father come to the morgue to identify his body. This skilful voice throwing is a vivid way of portraying a variety of individuals and their grief. ‘Kitchen’ offers a calmer voice re-visiting her mother’s house, the details and familiarity evoking simple things that have been lost in the death of the child: I’m guessing most of the poems I have referred to so far come from the early work of 2016. Other really strong pieces focus on events after the Fire itself. ‘Duppy’ is a sustained description – information slowly drip-fed – of a funeral or memorial meeting and it again becomes clear that the narrative voice is one of the dead: “No-one will tell me what happened to my body”. The title of the poem is a Jamaican word of African origin meaning spirit or ghost. ‘Stone’ is perhaps a rare recurrence of the author’s more autobiographical voice and in its scattered form and absence of punctuation reveals a tactful and beautiful lyrical gift as the narrator visits Fordham Park to sit beside the New Cross Fire’s memorial stone. ‘Songbook II’ is another chanted, hypnotic tribute to one of the mothers of the dead and is probably one of the poems Ali Smith is thinking of when she associates Bernard’s work with that of W.H. Auden.

I’m guessing most of the poems I have referred to so far come from the early work of 2016. Other really strong pieces focus on events after the Fire itself. ‘Duppy’ is a sustained description – information slowly drip-fed – of a funeral or memorial meeting and it again becomes clear that the narrative voice is one of the dead: “No-one will tell me what happened to my body”. The title of the poem is a Jamaican word of African origin meaning spirit or ghost. ‘Stone’ is perhaps a rare recurrence of the author’s more autobiographical voice and in its scattered form and absence of punctuation reveals a tactful and beautiful lyrical gift as the narrator visits Fordham Park to sit beside the New Cross Fire’s memorial stone. ‘Songbook II’ is another chanted, hypnotic tribute to one of the mothers of the dead and is probably one of the poems Ali Smith is thinking of when she associates Bernard’s work with that of W.H. Auden. But when the device of haunting and haunted voices is abandoned, Bernard’s work drifts quickly towards the literal and succumbs to the pressure to record events and places (the downside of the archival instinct). A tribute to Naomi Hersi, a black trans-woman found murdered in 2018, sadly doesn’t get much beyond plain location, a kind of reportage and admission that it is difficult to articulate feelings (‘Pem-People’). There are interesting pieces which read as autobiography – a childhood holiday in Jamaica, joining a Pride march, a sexual encounter in Camberwell, but on their own behalf Bernard seems curiously to have lost their eagle eye for the selection of telling details and tone and tension flatten out:

But when the device of haunting and haunted voices is abandoned, Bernard’s work drifts quickly towards the literal and succumbs to the pressure to record events and places (the downside of the archival instinct). A tribute to Naomi Hersi, a black trans-woman found murdered in 2018, sadly doesn’t get much beyond plain location, a kind of reportage and admission that it is difficult to articulate feelings (‘Pem-People’). There are interesting pieces which read as autobiography – a childhood holiday in Jamaica, joining a Pride march, a sexual encounter in Camberwell, but on their own behalf Bernard seems curiously to have lost their eagle eye for the selection of telling details and tone and tension flatten out: The mirroring architectonic of the collection emerges with the poems written about the Grenfell Tower fire. So we have ‘Ark II’, two pools of prose broken by slashes which seem to be fed by too many tributary streams: the silent marches in Ladbroke grove, the Michael Smithyman murder and abandoned investigation, Smithyman’s transition to Michelle, and the burning of the Grenfell Tower effigy, the video of which emerged in 2018.

The mirroring architectonic of the collection emerges with the poems written about the Grenfell Tower fire. So we have ‘Ark II’, two pools of prose broken by slashes which seem to be fed by too many tributary streams: the silent marches in Ladbroke grove, the Michael Smithyman murder and abandoned investigation, Smithyman’s transition to Michelle, and the burning of the Grenfell Tower effigy, the video of which emerged in 2018.

In a recent launch reading for her second collection, Dear Big Gods (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019), Mona Arshi suggested

In a recent launch reading for her second collection, Dear Big Gods (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019), Mona Arshi suggested As the blurb suggests, these poems are indeed “lyrical and exact exploration[s] of the aftershocks of grief”. But ‘Everywhere’ adopts a little more distance and develops the kind of floating and delicate lyricism that Arshi does so well. The absent brother/uncle is still alluded to: “We tell the children, we should not / look for him. He is everywhere”. As that final phrase suggests, the rawness of the grief is being transmuted into a sense of otherness, beyond the quotidian and material. It’s when Arshi takes her brother’s advice and lets go of “definitive knowledge” that her poems promise so much. ‘Little Prayer’ might be spoken by the dead or the living, left abandoned, but either way it argues a stoical resistance: “I am still here // hunkered down”. In a more conventional mode, ‘The Lilies’ develops the objective correlative of the flowers suffering from blight as an image of a spoliation that hurts and reminds, yet is allowed to persist: “I let them live on / beauty-drained / in their altar beds”.

As the blurb suggests, these poems are indeed “lyrical and exact exploration[s] of the aftershocks of grief”. But ‘Everywhere’ adopts a little more distance and develops the kind of floating and delicate lyricism that Arshi does so well. The absent brother/uncle is still alluded to: “We tell the children, we should not / look for him. He is everywhere”. As that final phrase suggests, the rawness of the grief is being transmuted into a sense of otherness, beyond the quotidian and material. It’s when Arshi takes her brother’s advice and lets go of “definitive knowledge” that her poems promise so much. ‘Little Prayer’ might be spoken by the dead or the living, left abandoned, but either way it argues a stoical resistance: “I am still here // hunkered down”. In a more conventional mode, ‘The Lilies’ develops the objective correlative of the flowers suffering from blight as an image of a spoliation that hurts and reminds, yet is allowed to persist: “I let them live on / beauty-drained / in their altar beds”.

Arshi’s continuing love affair with ghazals also seems to me to be an aspect of this same search for a form that holds both the connected and the stand-alone in a creative tension. ‘Ghazal: Darkness’ is very successful with the second line of each couplet returning to the refrain word, “darkness”, while the connective tissue of the poem allows a roaming through woods, soil, mushrooms and a mother’s praise of her daughters. Poems based on – or at least with the qualities of – dreams also stand out. The doctor in ‘Delivery Room’ asks the mother in the midst of her contractions, “Do you prefer the geometric or lyrical approach?” In ‘The Sisters’ the narrator dreams of “all the sisters I never had” and within 10 lines Arshi has expressed complex yearnings about loneliness and protectiveness in relation to siblings and self.

Arshi’s continuing love affair with ghazals also seems to me to be an aspect of this same search for a form that holds both the connected and the stand-alone in a creative tension. ‘Ghazal: Darkness’ is very successful with the second line of each couplet returning to the refrain word, “darkness”, while the connective tissue of the poem allows a roaming through woods, soil, mushrooms and a mother’s praise of her daughters. Poems based on – or at least with the qualities of – dreams also stand out. The doctor in ‘Delivery Room’ asks the mother in the midst of her contractions, “Do you prefer the geometric or lyrical approach?” In ‘The Sisters’ the narrator dreams of “all the sisters I never had” and within 10 lines Arshi has expressed complex yearnings about loneliness and protectiveness in relation to siblings and self. So, in ‘My Third Eye’, the narrator is “more perplexed than annoyed” that her own third eye – the mystical and esoteric belief in a speculative, spiritual perception – has not yet “opened”. The poem’s mode and tone is comic for the most part; there is a childish impatience in the voice, asking “Am I not as worthy as the buffalo, the ferryman, / the cook and the Dalit?”. But in the final lines, the holy man she visits is given more gravitas. He touches the narrator’s head “and with that my eyes suddenly watered, widened and / he sent me on my way as I was forever open open open”. The book also closes with the title poem, ‘Dear Big Gods’, which takes the form of a prayer: “all you have to do / is show yourself”, it pleads. The delicate probing of Arshi’s best poems, their stretching of perception and openness to unusual states of emotion are driven by this sort of spiritual quest. Personal tragedy has no doubt fed this creative drive but – as the poet seems to be aware – such grief is only an aspect of her vision and not the whole of it.

So, in ‘My Third Eye’, the narrator is “more perplexed than annoyed” that her own third eye – the mystical and esoteric belief in a speculative, spiritual perception – has not yet “opened”. The poem’s mode and tone is comic for the most part; there is a childish impatience in the voice, asking “Am I not as worthy as the buffalo, the ferryman, / the cook and the Dalit?”. But in the final lines, the holy man she visits is given more gravitas. He touches the narrator’s head “and with that my eyes suddenly watered, widened and / he sent me on my way as I was forever open open open”. The book also closes with the title poem, ‘Dear Big Gods’, which takes the form of a prayer: “all you have to do / is show yourself”, it pleads. The delicate probing of Arshi’s best poems, their stretching of perception and openness to unusual states of emotion are driven by this sort of spiritual quest. Personal tragedy has no doubt fed this creative drive but – as the poet seems to be aware – such grief is only an aspect of her vision and not the whole of it.

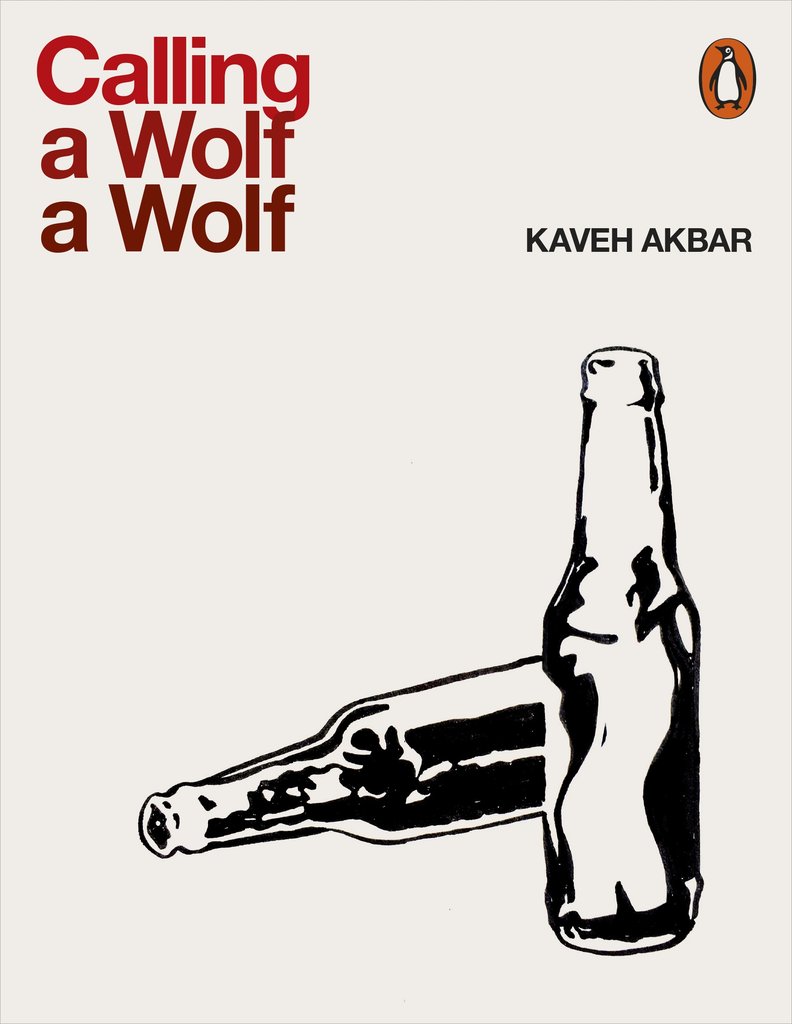

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

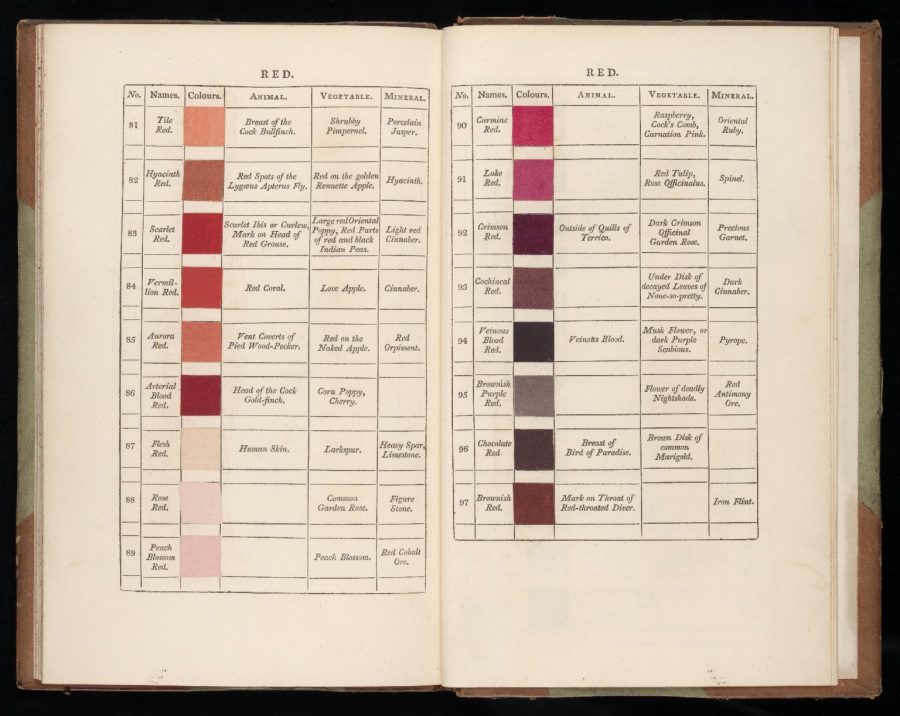

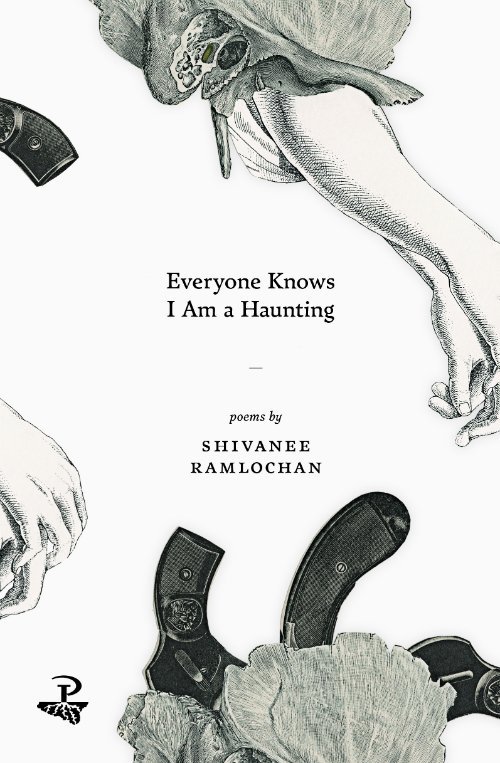

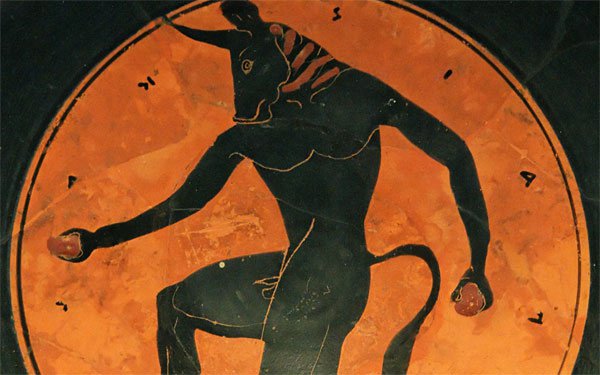

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.