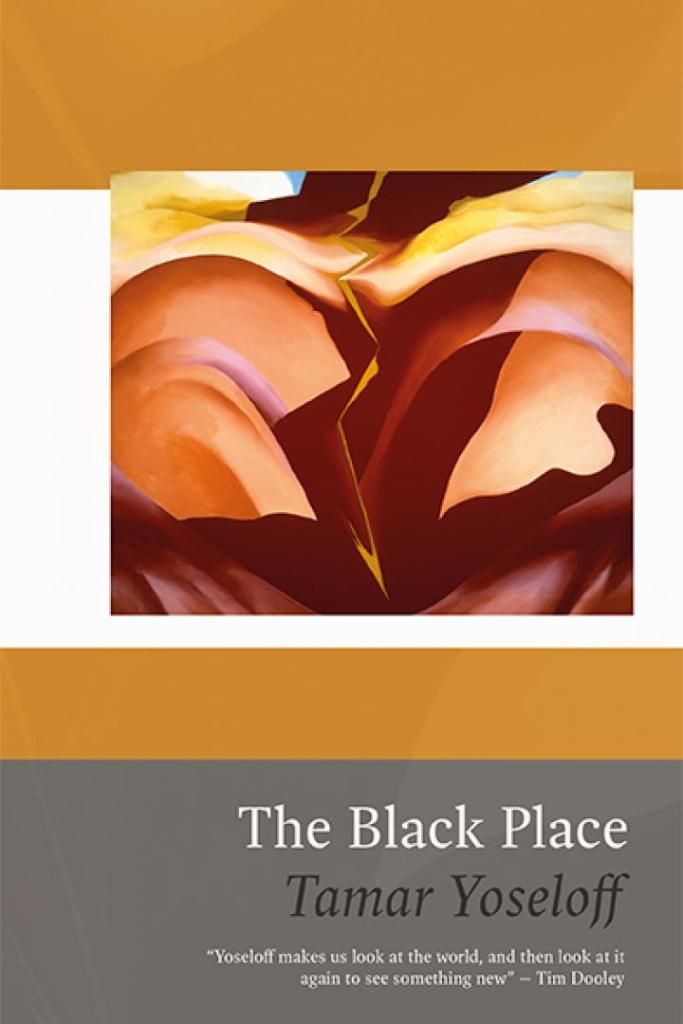

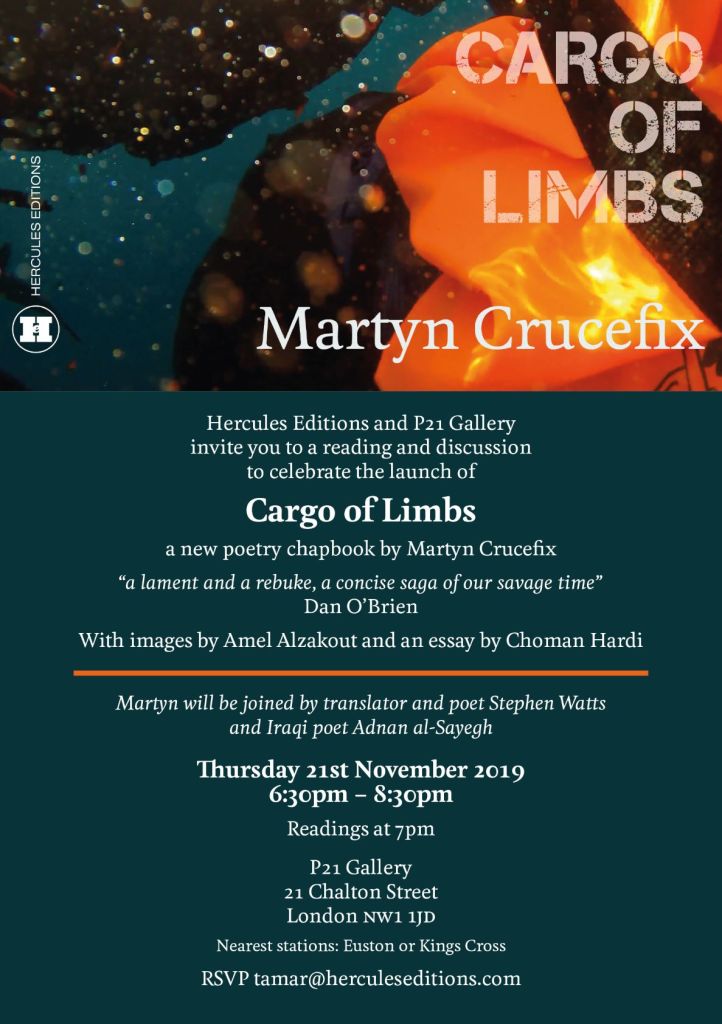

Last week I attended the launch of Tamar Yoseloff’s new collection, published by Seren Books. Tammy and I have known each other for a long while, are both published by Seren and, in her role at Hercules Editions, she has just published my own recent chapbook, Cargo of Limbs. So – in the small world of British poetry – I’m hardly an unconnected critic, but I have the benefit of having followed her work over the years, reviewing her most recent New and Selected, A Formula for Night (2015) here.

In an earlier blog post, I spoke – in rather tabloid-y terms – of the tension in Yoseloff’s poems between the “sassy and the sepulchral”. In 2007’s Fetch (Salt), there were “racy, blunt narratives” which in their exploration of female freedom, restraint and taboo made for vivid, exciting reading. The other side of her gift inclines to an “apocalyptic darkness”, a preoccupation with time, loss, the inability to hold the moment. In A Formula for Night, the poem ‘Ruin’ invented a form in which a text was gradually shot to pieces as phrases, even letters, were gradually edited out, displaying the very process of ruination. Interestingly, The Black Place develops this technique in 3 ‘redaction’ poems in which most of a text has been blacked out (cut out – see Yoko Ono later), leaving only a few telling words. A note indicates the source text in all three cases was the booklet Understanding Kidney Cancer and the author’s recent experience of illness is an important element in this new collection.

But unlike, for example, Lieke Marsman’s recent The Following Scan Will Last Five Minutes (Pavilion Poetry, 2019 – discussed here), Yoseloff’s book is not dominated by the experience of illness (and one feels this is a deliberated choice). The book opens with ‘The C Word’ which considers the phonetic parts of the word ‘cancer’, as well as its appearance: “looks like carer but isn’t”. But – within its 12 lines – Yoseloff also considers the other C word, “detonated in hate / murmured in love”. The poem is really about how an individual can contain such divergent elements, “sites of birth / and death”. So unanticipated personal experience is here being filtered through the matrix of this writer’s naturally ambivalent gift.

Illness re-emerges explicitly later in the collection, but for much of it there is a business as usual quality and I, for one, am inclined to admire this:

I refuse the confessional splurge,

the Facebook post, the hospital selfie.

I’m just another body, a statistic,

nothing special. Everyone dies –

get over yourself.

So Yoseloff gives us a marvellous send-up of Edward Thomas’ ‘Adlestrop’ in ‘Sheeple’, a central place on the darker side of Yoseloff-country: “The heartland. Lower Slaughter”. There is urbanite humour in ‘Holiday Cottage’ with its “stygian kitchen”, bad weather, boredom and kitsch:

We stare at the knock-off Hay Wain

hung crooked over the hearth

and dream of England: the shire bells,

the box set, the M&S biscuit tin

‘The Wayfarer’ is one of many ekphrastic poems here – this one based on a Bosch painting – but the “sunless land” is patently an England on which “God looked down / and spat”. These are poems written in the last 3 years or so and, inevitably, Brexit impinges, most obviously in ‘Islanders’ (“We put seas between ourselves, / we won’t be rescued”) but the cityscape equally offers little in the way of hope. There is a caricaturing quality to the life lived there: everything “pixilates, disneyfies” (‘Emoji’) and gender relationships seem warped by inequitable power, by self-destructive urges and illness: “I’d super-shrink my dimensions, / wasting is a form of perfection” (‘Walk All Over Me’).

Perhaps ‘Girl’ shows us the figure of a survivor in such a hostile environment, her energy reflecting those female figures in Fetch – “a slip, a trick, a single polka dot” – but the darkness seems thicker now, the lack of lyricism, the impossibility of a happy ending more resolved:

She’s good for nothing because nothing’s

good: sirens drown out violins

and crows swoop to carnage in the street.

As the blurb says, the book boldly eschews the sentimental sop, the capitalist hype, for truths that are hard, not to say brutal. ‘Little Black Dress’ takes both the archetypal ‘girl’ and the author herself from teen years to widowhood in a dizzyingly rapid sonnet-length poem:

drunk and disorderly, dropping off bar stools one

by one, until the time arrives for widow’s weeds

and weeping veils, Ray-Bans darkening the sun.

And it is – unsurprisingly – mortality (the sepulchral) that eventually comes to the fore. A notable absence is the author’s mother, who has often been a powerful presence in previous books. Here she re-appears briefly in ‘Jade’. The stone is reputed to be efficacious in curing ailments of the kidneys and a jade necklace inherited from Yoseloff’s mother leads her to wonder about the inheritance of disease too: “a slow / release in her body, passed down, // down”. Both parents put in a fleeting appearance in the powerful sequence ‘Darklight’, the third part of which opens with the narrator standing in a pool of streetlight, “holding the dark / at bay”. She supposes, rather hopelessly, that “this must be what it’s like to have a god”. Not an option available to her; the dark holds monsters both within and without and not just for the child:

Back then

my parents would sing me to sleep;

now they’re ash and bone. Our lives are brief

like the banks of candles in cathedrals,

each a flame for someone loved;

It’s these thoughts that further the careful structuring of this collection and return it to the experience of a life-threatening illness. ‘Nephritic Sonnet’ is an interrupted or cut off – 13 line – sonnet that takes us to the hospital ward, the I.V. tubes and – as she once said of the city – the poet finds “no poetry in the hospital gown”. Except, of course, that’s exactly what we get. The determination or need to write about even the bleakest of experiences is the defiant light being held up. Yoseloff does not rage; her style is quieter and involves a steady, undeceived gaze and also – in the sequence ‘Cuts’ – the powerful sense that (as quoted above) “I’m just another body, a statistic, / nothing special. Everyone dies”.

It’s this sense of being “nothing special” that enables ‘Cuts’ dispassionately to record very personal experiences of hospital procedures alongside the contemporaneous facts of the Grenfell Tower fire and (another ekphrastic element) a 1960s performance piece by Yoko Ono called ‘Cut Piece’. These elements are ‘leaned’ against each other in a series of 13 dismembered sonnets, each broken up into sections of 6/3/4/1 lines. The fragmentary, diaristic style works well though there are risks in equating personal illness with the catastrophic accident and vital political questions surrounding Grenfell. Ono’s performance piece offers a further example of victimhood, one more chosen and controllable perhaps. What’s impressive is how Yoseloff avoids the magnetic pull of the ego, displaying – if anything – a salutary empathy for others in the midst of her own fears.

The book is titled after a Georgia O’Keefe picture, reproduced on the cover. O’Keefe’s steady gaze into the darkness created by the jagged relief of the Navajo country is something to which Yoseloff aspires, though it “chills me / just to think it into being”. It is the ultimate reality – a nothing, le néant – though like the ultimate presence of other writers (Yves Bonnefoy’s le presence, for example), can at best only be gestured towards:

We’ll never find it; as soon as we arrive,

the distance shifts to somewhere else,

we remain in foreground, everything moving

around us, even when we’re still.

Along such a difficult path, Yoseloff insists, O’Keefe’s art found “the bellow in a skull, / the swagger in a flower”. And, even in the most frightening brush with her own mortality, the poet will follow and does so in a way that is consistent with her own nature and work over many years.

But Surge itself has since gone through various forms. There were 10 original poems written quickly in 2016. There was a performance piece (at London’s Roundhouse) in the summer of 2017 (it was this version that won the Ted Hughes Award for New Work in poetry in 2017). But it has taken 3 years for this Chatto book to be finalised. In an interview just last year, Bernard observed that they were still unclear what the “final structure” of the material would be. I’m possessed of no insider knowledge on this, but it looks as if this “final” version took some considerable effort – reading it makes me conscious of the strait-jacket that a conventional slim volume of poetry imposes – and I’m not sure the finalised 50-odd pages of the collection really act as the best foil for what are, without doubt, a series of stunningly powerful poems. The blurb and publicity present the book (as publishers so often do) as wholly focused on the New Cross and Grenfell fires but this isn’t really true and something is lost in including the more miscellaneous pieces, particularly towards the end of the book.

But Surge itself has since gone through various forms. There were 10 original poems written quickly in 2016. There was a performance piece (at London’s Roundhouse) in the summer of 2017 (it was this version that won the Ted Hughes Award for New Work in poetry in 2017). But it has taken 3 years for this Chatto book to be finalised. In an interview just last year, Bernard observed that they were still unclear what the “final structure” of the material would be. I’m possessed of no insider knowledge on this, but it looks as if this “final” version took some considerable effort – reading it makes me conscious of the strait-jacket that a conventional slim volume of poetry imposes – and I’m not sure the finalised 50-odd pages of the collection really act as the best foil for what are, without doubt, a series of stunningly powerful poems. The blurb and publicity present the book (as publishers so often do) as wholly focused on the New Cross and Grenfell fires but this isn’t really true and something is lost in including the more miscellaneous pieces, particularly towards the end of the book. Bernard’s poetic voice is at its best when making full use of the licence of free forms, broken grammar, infrequent punctuation, the colloquial voice and often incantatory patois. So a voice in ‘Harbour’ wanders across the page, hesitantly, uncertainly, till images of heat, choking and breaking glass make it clear this is someone caught in the New Cross Fire. Another voice in ‘Clearing’ watches, in the aftermath of the blaze, as an officer collect body parts (including the voice’s own body): “from the bag I watch his face turn away”. The cryptically titled ‘+’ and ‘–’ shift to broken, dialogic prose as a father is asked to identify his dead son through the clothes he was wearing. Then the son’s voice cries out for and watches his father come to the morgue to identify his body. This skilful voice throwing is a vivid way of portraying a variety of individuals and their grief. ‘Kitchen’ offers a calmer voice re-visiting her mother’s house, the details and familiarity evoking simple things that have been lost in the death of the child:

Bernard’s poetic voice is at its best when making full use of the licence of free forms, broken grammar, infrequent punctuation, the colloquial voice and often incantatory patois. So a voice in ‘Harbour’ wanders across the page, hesitantly, uncertainly, till images of heat, choking and breaking glass make it clear this is someone caught in the New Cross Fire. Another voice in ‘Clearing’ watches, in the aftermath of the blaze, as an officer collect body parts (including the voice’s own body): “from the bag I watch his face turn away”. The cryptically titled ‘+’ and ‘–’ shift to broken, dialogic prose as a father is asked to identify his dead son through the clothes he was wearing. Then the son’s voice cries out for and watches his father come to the morgue to identify his body. This skilful voice throwing is a vivid way of portraying a variety of individuals and their grief. ‘Kitchen’ offers a calmer voice re-visiting her mother’s house, the details and familiarity evoking simple things that have been lost in the death of the child: I’m guessing most of the poems I have referred to so far come from the early work of 2016. Other really strong pieces focus on events after the Fire itself. ‘Duppy’ is a sustained description – information slowly drip-fed – of a funeral or memorial meeting and it again becomes clear that the narrative voice is one of the dead: “No-one will tell me what happened to my body”. The title of the poem is a Jamaican word of African origin meaning spirit or ghost. ‘Stone’ is perhaps a rare recurrence of the author’s more autobiographical voice and in its scattered form and absence of punctuation reveals a tactful and beautiful lyrical gift as the narrator visits Fordham Park to sit beside the New Cross Fire’s memorial stone. ‘Songbook II’ is another chanted, hypnotic tribute to one of the mothers of the dead and is probably one of the poems Ali Smith is thinking of when she associates Bernard’s work with that of W.H. Auden.

I’m guessing most of the poems I have referred to so far come from the early work of 2016. Other really strong pieces focus on events after the Fire itself. ‘Duppy’ is a sustained description – information slowly drip-fed – of a funeral or memorial meeting and it again becomes clear that the narrative voice is one of the dead: “No-one will tell me what happened to my body”. The title of the poem is a Jamaican word of African origin meaning spirit or ghost. ‘Stone’ is perhaps a rare recurrence of the author’s more autobiographical voice and in its scattered form and absence of punctuation reveals a tactful and beautiful lyrical gift as the narrator visits Fordham Park to sit beside the New Cross Fire’s memorial stone. ‘Songbook II’ is another chanted, hypnotic tribute to one of the mothers of the dead and is probably one of the poems Ali Smith is thinking of when she associates Bernard’s work with that of W.H. Auden. But when the device of haunting and haunted voices is abandoned, Bernard’s work drifts quickly towards the literal and succumbs to the pressure to record events and places (the downside of the archival instinct). A tribute to Naomi Hersi, a black trans-woman found murdered in 2018, sadly doesn’t get much beyond plain location, a kind of reportage and admission that it is difficult to articulate feelings (‘Pem-People’). There are interesting pieces which read as autobiography – a childhood holiday in Jamaica, joining a Pride march, a sexual encounter in Camberwell, but on their own behalf Bernard seems curiously to have lost their eagle eye for the selection of telling details and tone and tension flatten out:

But when the device of haunting and haunted voices is abandoned, Bernard’s work drifts quickly towards the literal and succumbs to the pressure to record events and places (the downside of the archival instinct). A tribute to Naomi Hersi, a black trans-woman found murdered in 2018, sadly doesn’t get much beyond plain location, a kind of reportage and admission that it is difficult to articulate feelings (‘Pem-People’). There are interesting pieces which read as autobiography – a childhood holiday in Jamaica, joining a Pride march, a sexual encounter in Camberwell, but on their own behalf Bernard seems curiously to have lost their eagle eye for the selection of telling details and tone and tension flatten out: The mirroring architectonic of the collection emerges with the poems written about the Grenfell Tower fire. So we have ‘Ark II’, two pools of prose broken by slashes which seem to be fed by too many tributary streams: the silent marches in Ladbroke grove, the Michael Smithyman murder and abandoned investigation, Smithyman’s transition to Michelle, and the burning of the Grenfell Tower effigy, the video of which emerged in 2018.

The mirroring architectonic of the collection emerges with the poems written about the Grenfell Tower fire. So we have ‘Ark II’, two pools of prose broken by slashes which seem to be fed by too many tributary streams: the silent marches in Ladbroke grove, the Michael Smithyman murder and abandoned investigation, Smithyman’s transition to Michelle, and the burning of the Grenfell Tower effigy, the video of which emerged in 2018. In a recent launch reading for her second collection, Dear Big Gods (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019), Mona Arshi suggested

In a recent launch reading for her second collection, Dear Big Gods (Pavilion Poetry/Liverpool University Press, 2019), Mona Arshi suggested As the blurb suggests, these poems are indeed “lyrical and exact exploration[s] of the aftershocks of grief”. But ‘Everywhere’ adopts a little more distance and develops the kind of floating and delicate lyricism that Arshi does so well. The absent brother/uncle is still alluded to: “We tell the children, we should not / look for him. He is everywhere”. As that final phrase suggests, the rawness of the grief is being transmuted into a sense of otherness, beyond the quotidian and material. It’s when Arshi takes her brother’s advice and lets go of “definitive knowledge” that her poems promise so much. ‘Little Prayer’ might be spoken by the dead or the living, left abandoned, but either way it argues a stoical resistance: “I am still here // hunkered down”. In a more conventional mode, ‘The Lilies’ develops the objective correlative of the flowers suffering from blight as an image of a spoliation that hurts and reminds, yet is allowed to persist: “I let them live on / beauty-drained / in their altar beds”.

As the blurb suggests, these poems are indeed “lyrical and exact exploration[s] of the aftershocks of grief”. But ‘Everywhere’ adopts a little more distance and develops the kind of floating and delicate lyricism that Arshi does so well. The absent brother/uncle is still alluded to: “We tell the children, we should not / look for him. He is everywhere”. As that final phrase suggests, the rawness of the grief is being transmuted into a sense of otherness, beyond the quotidian and material. It’s when Arshi takes her brother’s advice and lets go of “definitive knowledge” that her poems promise so much. ‘Little Prayer’ might be spoken by the dead or the living, left abandoned, but either way it argues a stoical resistance: “I am still here // hunkered down”. In a more conventional mode, ‘The Lilies’ develops the objective correlative of the flowers suffering from blight as an image of a spoliation that hurts and reminds, yet is allowed to persist: “I let them live on / beauty-drained / in their altar beds”.

Arshi’s continuing love affair with ghazals also seems to me to be an aspect of this same search for a form that holds both the connected and the stand-alone in a creative tension. ‘Ghazal: Darkness’ is very successful with the second line of each couplet returning to the refrain word, “darkness”, while the connective tissue of the poem allows a roaming through woods, soil, mushrooms and a mother’s praise of her daughters. Poems based on – or at least with the qualities of – dreams also stand out. The doctor in ‘Delivery Room’ asks the mother in the midst of her contractions, “Do you prefer the geometric or lyrical approach?” In ‘The Sisters’ the narrator dreams of “all the sisters I never had” and within 10 lines Arshi has expressed complex yearnings about loneliness and protectiveness in relation to siblings and self.

Arshi’s continuing love affair with ghazals also seems to me to be an aspect of this same search for a form that holds both the connected and the stand-alone in a creative tension. ‘Ghazal: Darkness’ is very successful with the second line of each couplet returning to the refrain word, “darkness”, while the connective tissue of the poem allows a roaming through woods, soil, mushrooms and a mother’s praise of her daughters. Poems based on – or at least with the qualities of – dreams also stand out. The doctor in ‘Delivery Room’ asks the mother in the midst of her contractions, “Do you prefer the geometric or lyrical approach?” In ‘The Sisters’ the narrator dreams of “all the sisters I never had” and within 10 lines Arshi has expressed complex yearnings about loneliness and protectiveness in relation to siblings and self. So, in ‘My Third Eye’, the narrator is “more perplexed than annoyed” that her own third eye – the mystical and esoteric belief in a speculative, spiritual perception – has not yet “opened”. The poem’s mode and tone is comic for the most part; there is a childish impatience in the voice, asking “Am I not as worthy as the buffalo, the ferryman, / the cook and the Dalit?”. But in the final lines, the holy man she visits is given more gravitas. He touches the narrator’s head “and with that my eyes suddenly watered, widened and / he sent me on my way as I was forever open open open”. The book also closes with the title poem, ‘Dear Big Gods’, which takes the form of a prayer: “all you have to do / is show yourself”, it pleads. The delicate probing of Arshi’s best poems, their stretching of perception and openness to unusual states of emotion are driven by this sort of spiritual quest. Personal tragedy has no doubt fed this creative drive but – as the poet seems to be aware – such grief is only an aspect of her vision and not the whole of it.

So, in ‘My Third Eye’, the narrator is “more perplexed than annoyed” that her own third eye – the mystical and esoteric belief in a speculative, spiritual perception – has not yet “opened”. The poem’s mode and tone is comic for the most part; there is a childish impatience in the voice, asking “Am I not as worthy as the buffalo, the ferryman, / the cook and the Dalit?”. But in the final lines, the holy man she visits is given more gravitas. He touches the narrator’s head “and with that my eyes suddenly watered, widened and / he sent me on my way as I was forever open open open”. The book also closes with the title poem, ‘Dear Big Gods’, which takes the form of a prayer: “all you have to do / is show yourself”, it pleads. The delicate probing of Arshi’s best poems, their stretching of perception and openness to unusual states of emotion are driven by this sort of spiritual quest. Personal tragedy has no doubt fed this creative drive but – as the poet seems to be aware – such grief is only an aspect of her vision and not the whole of it.

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

![moulin-glacier-11[2]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/moulin-glacier-112.jpg)

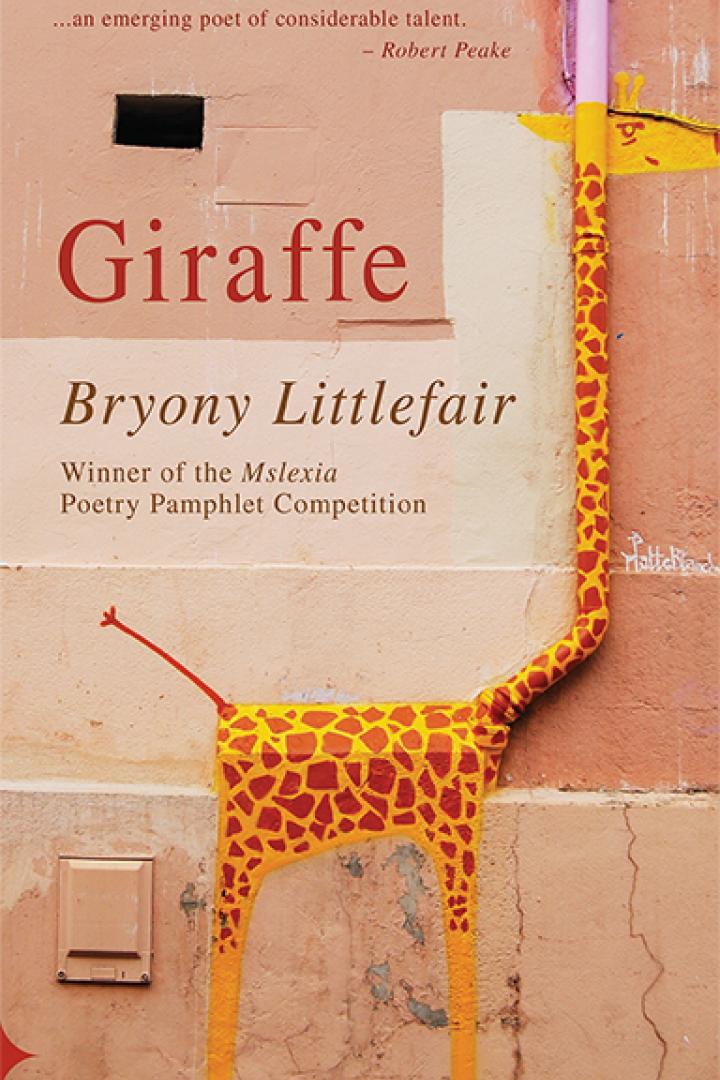

Another young female narrator deliberately stays at home while her parents (conventionally) go to church on Sundays. She’s a teenage rebel without a cause as “The truth is I’m not sure what I did / those mornings”. The poem is built from a list (one of Littlefair’s favourite forms) of what she did and did not do. Littlefair is almost always good with her figurative language and here the girl is variously an undone shoelace, an open rucksack, a blunt knife. The urge to non-conformity outruns her imagination as to how she might spend her growing independence and there is an interesting tension at the last as her parents return, “whole” having “sung their hallelujahs” while the young girl is till restlessly revising her choice of nail polish, as yet unable to find what she’s after.

Another young female narrator deliberately stays at home while her parents (conventionally) go to church on Sundays. She’s a teenage rebel without a cause as “The truth is I’m not sure what I did / those mornings”. The poem is built from a list (one of Littlefair’s favourite forms) of what she did and did not do. Littlefair is almost always good with her figurative language and here the girl is variously an undone shoelace, an open rucksack, a blunt knife. The urge to non-conformity outruns her imagination as to how she might spend her growing independence and there is an interesting tension at the last as her parents return, “whole” having “sung their hallelujahs” while the young girl is till restlessly revising her choice of nail polish, as yet unable to find what she’s after.

I think I find this with some other poems too, though it’s partly because Littlefair is admirably intent on presenting the working world, the world of labour, as routine in contrast to the allure of a more adventurous life. ‘Assignment brief’ presents itself as an old familiar’s introduction to a new girl’s routine office job; the lists and proffered options are funny but they slowly run out of steam. Likewise, the promisingly titled ‘Usually, I’m a different person at this party’ flags latterly. I’m imagining this as narrated by an older version of the girl who half fell in love with Tara Miller. Here, she shadow-boxes the risks of conventionality by over-insisting on her own sweeping and glamorous life, in the process claiming all sorts of ‘interesting’ aspects of herself: “I only ever have large and sweeping illnesses. / My lymph nodes swell glamorously. I never snuffle”. But the contrasts here are again rather roughly hewn and, in the end, close to cartoonish.

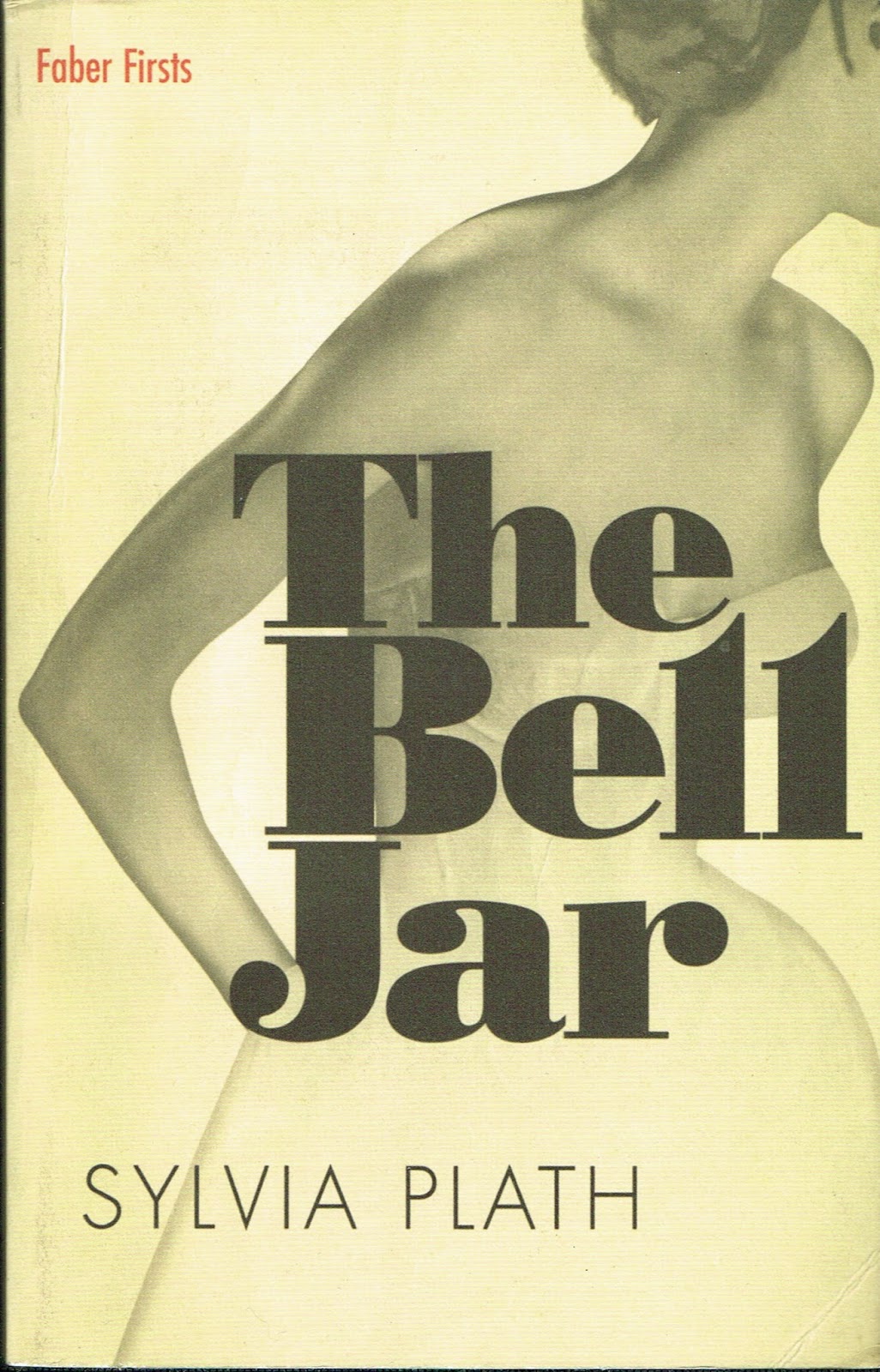

I think I find this with some other poems too, though it’s partly because Littlefair is admirably intent on presenting the working world, the world of labour, as routine in contrast to the allure of a more adventurous life. ‘Assignment brief’ presents itself as an old familiar’s introduction to a new girl’s routine office job; the lists and proffered options are funny but they slowly run out of steam. Likewise, the promisingly titled ‘Usually, I’m a different person at this party’ flags latterly. I’m imagining this as narrated by an older version of the girl who half fell in love with Tara Miller. Here, she shadow-boxes the risks of conventionality by over-insisting on her own sweeping and glamorous life, in the process claiming all sorts of ‘interesting’ aspects of herself: “I only ever have large and sweeping illnesses. / My lymph nodes swell glamorously. I never snuffle”. But the contrasts here are again rather roughly hewn and, in the end, close to cartoonish. The latter view is more than a possibility given that Littlefair’s poems also boldly explore the self’s relation with itself. The encounter between self and future self is plainly and humorously told in ‘Visitations from future self’ and it finds the present self in trouble, pleading “I can’t go on / like this, my life a tap that won’t / switch on”. Here, the present self’s cliched and optimistic hopes for a “rain-before-the-rainbow thing” are denigrated and stared down by the future self. ‘Sertraline’ echoes Plath’s The Bell Jar in its evocation of a summer spent on an anti-depressive drug. And ‘Giraffe’ itself is a prose poem (there are 3 prose pieces in the whole book) in which a voice is offering reassurances to someone hoping to “feel better”. In a final list, images of a return to ‘health’ are offered. Particularly good is the idea that suffering will remain a fact but “your sadness will be graspable, roadworthy, have handlebars”. And lastly, “When you feel better, you will not always be happy, but when happiness does come, it will be long-legged, sun-dappled: a giraffe.”

The latter view is more than a possibility given that Littlefair’s poems also boldly explore the self’s relation with itself. The encounter between self and future self is plainly and humorously told in ‘Visitations from future self’ and it finds the present self in trouble, pleading “I can’t go on / like this, my life a tap that won’t / switch on”. Here, the present self’s cliched and optimistic hopes for a “rain-before-the-rainbow thing” are denigrated and stared down by the future self. ‘Sertraline’ echoes Plath’s The Bell Jar in its evocation of a summer spent on an anti-depressive drug. And ‘Giraffe’ itself is a prose poem (there are 3 prose pieces in the whole book) in which a voice is offering reassurances to someone hoping to “feel better”. In a final list, images of a return to ‘health’ are offered. Particularly good is the idea that suffering will remain a fact but “your sadness will be graspable, roadworthy, have handlebars”. And lastly, “When you feel better, you will not always be happy, but when happiness does come, it will be long-legged, sun-dappled: a giraffe.” The designation ‘a young poet to watch’ is over-used but on this occasion it needs to be said loudly. Giraffe contains a number of fresh, intriguing and fully-achieved poems. It’s well worth seeking out. I well remember reading and being very impressed by Liz Berry’s 2010 Tall Lighthouse debut chapbook, the patron saint of schoolgirls, and this selection from Bryony Littlefair’s early work runs it close. My review of Liz Berry’s subsequent, prize-winning full collection,

The designation ‘a young poet to watch’ is over-used but on this occasion it needs to be said loudly. Giraffe contains a number of fresh, intriguing and fully-achieved poems. It’s well worth seeking out. I well remember reading and being very impressed by Liz Berry’s 2010 Tall Lighthouse debut chapbook, the patron saint of schoolgirls, and this selection from Bryony Littlefair’s early work runs it close. My review of Liz Berry’s subsequent, prize-winning full collection,