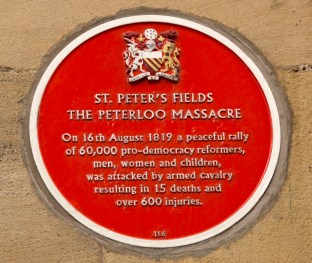

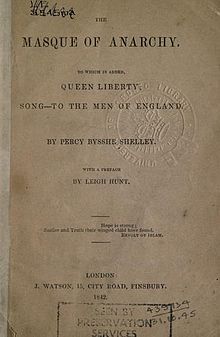

I hope you have read my earlier post on this subject because here comes my commentary on the second half of Shelley’s The Mask of Anarchy. It’s the poem he wrote in response to the so-called Peterloo Massacre on 16 August 1819 and one that Richard Holmes and Paul Foot have called “the greatest poem of political protest ever written in English”. I was sent back to the poem after having watched Mike Leigh’s recent film Peterloo – which I would recommend to those interested in the politics of the early 19th century as much as the politics of today. The political climate at the time (as Leigh’s film so vividly demonstrates) was increasingly repressive in regard to any speech or publication in favour of Reform and because of fears of prosecution the poem only saw the light of day after the Reform Bill had been passed in 1832.

Earth Speaks: on the Nature of Slavery (ll. 147-212)

So, Earth now speaks the imperative injunctions that many people will recognise. She first addresses the men of England as rightful and eventual “heirs of Glory” and nurslings “of one mighty Mother” which must be a reference to herself. Then, in what sounds like a call to battle, she cries:

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number,

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you —

Ye are many — they are few.

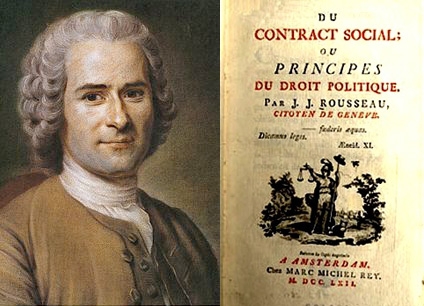

Though the nobility of lions is proverbial, so is their ferocity and here again it’s hard not to hear a call to arms as well as a shucking off of political chains that have imprisoned the Rousseauistic noble savage.

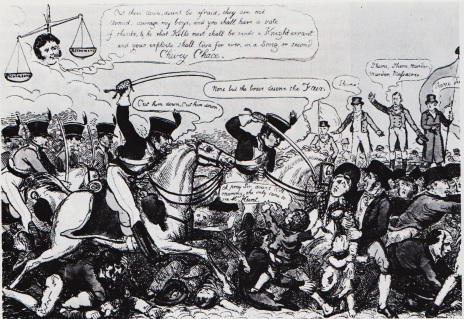

Earth continues by diagnosing the state of slavery into which England has fallen. This – and the following passage with its more positive analysis of what Freedom means to working people – makes for powerful, relevant, realistic reading in contrast to Shelley’s hard-to-pin-down mechanisms of political change. Slavery is to have to work and be paid only enough to live for another day’s work. It is to work not for oneself but for “tyrants”. It is to see family suffering and dying, to go hungry while the rich man surfeits his dogs. It is to suffer the “forgery” of paper money, to have no control over one’s own destiny. It is – when driven to the point of protest – a more direct reference to events in Manchester – “to see the Tyrant’s crew / Ride over your wives and you”.

Earth continues by diagnosing the state of slavery into which England has fallen. This – and the following passage with its more positive analysis of what Freedom means to working people – makes for powerful, relevant, realistic reading in contrast to Shelley’s hard-to-pin-down mechanisms of political change. Slavery is to have to work and be paid only enough to live for another day’s work. It is to work not for oneself but for “tyrants”. It is to see family suffering and dying, to go hungry while the rich man surfeits his dogs. It is to suffer the “forgery” of paper money, to have no control over one’s own destiny. It is – when driven to the point of protest – a more direct reference to events in Manchester – “to see the Tyrant’s crew / Ride over your wives and you”.

The remaining stanzas of this part of the poem contrast the plight of English working people to that of animals both wild and domesticated: the animals are better off. But lines 192-195 are especially interesting. In the face of such slavery, the narrator says, it is likely that the desire for vengeance will arise:

Then it is to feel revenge

Fiercely thirsting to exchange

Blood for blood – and wrong for wrong –

But such a use of force, when a degree of power has been achieved, resulting in further bloodshed, is here explicitly rejected: “Do not thus when ye are strong”. This theme of not answering violence with violence is developed much more clearly later and it’s difficult to square this with the earlier images in the poem of Hope “ankle-deep in blood”.

Earth Speaks: On the Nature of Freedom

Now earth’s imagined voice sets about answering more positively, indeed in downright terms, her own question: “What art thou Freedom?” It is not an abstraction, “A shadow . . . / A superstition . . . a name”. Rather it is the provision of bread on the table, of clothes, of fire. As Anarchy was really the law of the rich, so Freedom assumes a strong legal system to prevent exploitation of the poor by the rich. Freedom is therefore justice available to the poor as well as the rich, to protect both “high and low”. Freedom is also wisdom – this must be partly the kind of free thinking (l. 125) generated by the Shape conjured by Hope and certainly (as always for Shelley) it means a thoroughly sceptical take on the teachings of the Christian church. Freedom is also peace – Shelley regarded the war on post-Revolutionary France in 1793 as a war against Freedom.

Freedom is also love – the examples given here suggesting a narrower definition than earlier in the poem. But love is accorded a Christ-like comparison in that some of “the rich” abandon their wealth to follow him and the cause of Freedom, indeed they turn their “wealth to arms” to combat the iniquitous influence of “wealth, and war, and fraud”. The paradox of taking up arms against war itself again perhaps highlights confusion in Shelley’s thinking though the kind of rich man he must have in mind here is Orator Henry Hunt (brilliantly played by Rory Kinnear in Leigh’s film) whose commitment to the cause of Reform was genuine (if a little self-regarding).

This passage ends less effectively with something of a shopping-list of abstract qualities which also comprise the nature of Freedom: Science, Poetry, Thought, Spirit, Patience and Gentleness”. Shelley himself may sense the dropped poetical pressure as the earth here sweeps aside the risky cheapness of such words in favour of actions: “let deeds, not words, express / Thine exceeding loveliness”.

Earth Speaks: Making a Call to a Great Assembly

In this section Shelley puts aside any ambiguity as to the nature of the action required to achieve political change. Through earth’s voice he demands more occasions like the St Peter’s Field gathering.

Let a great Assembly be

Of the fearless and the free

On some spot of English ground

Where the plains stretch wide around.

People must assemble from all “corners” of the nation including palaces of the rich where “some few feel such compassion / For those who groan, and toil, and wail / As must make their brethren pale”. The purpose of the assembly will be (as at Peterloo) to declare and demand the freedom of the people. These words will be “measured” and it is they that will serve as weapons (swords and shields). Here, Shelley’s belief in passive resistance is quite explicit in contrast to earlier in the poem. The narrator anticipates the establishment’s potentially violent response to such assemblies. But the repeated phrase “Let the . . .” drives home the point of passive resistance:

Let the tyrants pour around

With a quick and startling sound,

Like the loosening of a sea,

Troops of armed emblazonry.

Let the charged artillery drive

Till the dead air seems alive

With the clash of clanging wheels,

And the tramp of horses’ heels.

Let the fixèd bayonet

Gleam with sharp desire to wet

Its bright point in English blood

Looking keen as one for food.

Let the horsemen’s scimitars

Wheel and flash, like sphereless stars

Thirsting to eclipse their burning

In a sea of death and mourning.

Earth Speaks: on the Need for and Efficacy of Passive Resistance

Safe, if unhappy, in Italy it might have seemed easy for Shelley to have been recommending this course. But he does so, imaging the passively resisting working people of England as “a forest close and mute, / With folded arms and looks which are / Weapons of unvanquished war”. Such a non-militaristic “phalanx” will remain “undismayed”, he argues, and eventually victorious for three reasons. One is that the “old laws of England” will offer them some protection. These laws are personified as wise men, now old but “Children of a wiser day” from an imagined period of Rousseauistic natural justice and freedom. But their protection is by no means strong – indeed it seems pretty flimsy. Shelley still envisages Peterloo style violence from the powers that currently rule England. But this must still to be met with passive defiance:

And if then the tyrants dare

Let them ride among you there,

Slash, and stab, and maim, and hew,–

What they like, that let them do.

With folded arms and steady eyes,

And little fear, and less surprise,

Look upon them as they slay

Till their rage has died away.

The fading of such aggression is probably linked to the second reason for the cause of Liberty’s ultimate victory. This is hardly stronger than the first: it is that the perpetrators of violence against the people will be shamed and ashamed of their actions. The blood they shed will reappear as shameful “hot blushes on their cheek”. Women will cut them dead in the street. And true soldiers will turn from them towards the people, “those who would be free”.

The third reason Shelley gives – via the voice of the earth – also offers only equivocal, indeed very uncomfortable, hope. Offering little or no consolation to the victims and their relations – though a point proven true through many centuries – such massacres by repressive forces will prove an inspiration to those who come after them: “that slaughter to the Nation / Shall steam up like inspiration”. Using another of his images for revolutionary fervour, this steam will eventually result in a volcanic explosion, “heard afar”. Once more in this poem, these reverberations are translated into words to mark “Oppression’s thundered doom”, stirring the people in their on-going fight for justice and liberty. Shelley concludes with the actual words he imagines being uttered – and we have heard them before:

The third reason Shelley gives – via the voice of the earth – also offers only equivocal, indeed very uncomfortable, hope. Offering little or no consolation to the victims and their relations – though a point proven true through many centuries – such massacres by repressive forces will prove an inspiration to those who come after them: “that slaughter to the Nation / Shall steam up like inspiration”. Using another of his images for revolutionary fervour, this steam will eventually result in a volcanic explosion, “heard afar”. Once more in this poem, these reverberations are translated into words to mark “Oppression’s thundered doom”, stirring the people in their on-going fight for justice and liberty. Shelley concludes with the actual words he imagines being uttered – and we have heard them before:

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number–

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you–

Ye are many — they are few.

At which point the poem ends, still with the imagined voice of the earth speaking, repeating herself and the impression is of some circularity in the argument though this is really one of Shelley’s core beliefs: the fight for freedom and justice is never once and for all. The enemy will re-group so the cause of the people requires a continued alertness and watchfulness as well as the offer of resistance (passive for the most part, but perhaps with occasions of violence).

But as Shelley’s sentence crosses the next stanza break – ie. without any clear pause – the seemingly unstoppable parade of bloodshed, inequality, injustice and hypocrisy is strangely interrupted by a counter personification. A crazed-looking young woman (“a maniac maid”) runs out declaring that her name is Hope, though the narrator says “she looked more like Despair”. The perception here is interesting as even Shelley’s narrator has been so infected by the toxic atmosphere spread by Anarchy that the girl (who is soon to bring about a challenge to Anarchy) looks to be insane and more resembles the absence of hope than otherwise. This is one of Shelley’s core political beliefs and had already appeared in the closing lines of Prometheus Unbound. There, Demogorgon urges optimism in the long term conflict with abusive power: “to hope, till Hope creates / From its own wreck the thing it contemplates”. The movement for Reform will – it seems – have to come close to despair, or its own wreck, before the powers of Anarchy are likely to be defeated.

But as Shelley’s sentence crosses the next stanza break – ie. without any clear pause – the seemingly unstoppable parade of bloodshed, inequality, injustice and hypocrisy is strangely interrupted by a counter personification. A crazed-looking young woman (“a maniac maid”) runs out declaring that her name is Hope, though the narrator says “she looked more like Despair”. The perception here is interesting as even Shelley’s narrator has been so infected by the toxic atmosphere spread by Anarchy that the girl (who is soon to bring about a challenge to Anarchy) looks to be insane and more resembles the absence of hope than otherwise. This is one of Shelley’s core political beliefs and had already appeared in the closing lines of Prometheus Unbound. There, Demogorgon urges optimism in the long term conflict with abusive power: “to hope, till Hope creates / From its own wreck the thing it contemplates”. The movement for Reform will – it seems – have to come close to despair, or its own wreck, before the powers of Anarchy are likely to be defeated. This mist – later called a “Shape” – is one of the mysteries of the poem’s politics. Hope provokes its appearance. At first weak, it gathers in strength. Shelley compares it to clouds that gather “Like tower-crowned giants striding fast, / And glare with lightnings as they fly, /And speak in thunder to the sky”. In the next few stanzas it becomes more soldierly, “arrayed in mail”, compared to the scales of a snake (for Shelley the snake was usually an image of just rebellion not of evil), yet it is also winged. It wears a helmet with the image of the planet Venus on it. It moves softly and swiftly – a sensed but almost unseen presence. And rather than any military action or campaign of civil disobedience, this Shape, conjured by Hope, creates thinking:

This mist – later called a “Shape” – is one of the mysteries of the poem’s politics. Hope provokes its appearance. At first weak, it gathers in strength. Shelley compares it to clouds that gather “Like tower-crowned giants striding fast, / And glare with lightnings as they fly, /And speak in thunder to the sky”. In the next few stanzas it becomes more soldierly, “arrayed in mail”, compared to the scales of a snake (for Shelley the snake was usually an image of just rebellion not of evil), yet it is also winged. It wears a helmet with the image of the planet Venus on it. It moves softly and swiftly – a sensed but almost unseen presence. And rather than any military action or campaign of civil disobedience, this Shape, conjured by Hope, creates thinking: Yet in the calm aftermath of these events, there comes a sense of renovation, a “sense awakening and yet tender / Was heard and felt” and, most importantly, there are further words. This time the speaker is unclear though it is “As if” the earth itself, the mother of English men and women, feeling such bloodshed on her brow, translates this spilt blood into a powerful, irresistible language, “an accent unwithstood”. Shelley repeats “As if” once more, confirming the mystery of this voice, a voice which proceeds now to speak the whole of the remainder of the poem. For Shelley, Poetry in his broad sense is “vitally metaphorical” and the earth’s imagined speeches convey a sense that the cause of liberty is in accordance with the truly understood (surely Rousseauistic) nature of creation.

Yet in the calm aftermath of these events, there comes a sense of renovation, a “sense awakening and yet tender / Was heard and felt” and, most importantly, there are further words. This time the speaker is unclear though it is “As if” the earth itself, the mother of English men and women, feeling such bloodshed on her brow, translates this spilt blood into a powerful, irresistible language, “an accent unwithstood”. Shelley repeats “As if” once more, confirming the mystery of this voice, a voice which proceeds now to speak the whole of the remainder of the poem. For Shelley, Poetry in his broad sense is “vitally metaphorical” and the earth’s imagined speeches convey a sense that the cause of liberty is in accordance with the truly understood (surely Rousseauistic) nature of creation.

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).

The next section of the poem displays some of Lorca’s startling, surprising images: the “stars of frost”, the “fish of shadows”, the fig-tree’s “sandpaper branches”, the mountain is a “a thieving cat” that “bristles its sour agaves”. These are good examples of Lorca’s technique with metaphor: to place together two things which had always been considered as belonging to two different worlds, and in that fusion and shock to give them both a new reality. But these lines are perhaps really more about raising the narrative tensions in the poem through rhetorical questions such as, “But who will come? And where from?”

The next section of the poem displays some of Lorca’s startling, surprising images: the “stars of frost”, the “fish of shadows”, the fig-tree’s “sandpaper branches”, the mountain is a “a thieving cat” that “bristles its sour agaves”. These are good examples of Lorca’s technique with metaphor: to place together two things which had always been considered as belonging to two different worlds, and in that fusion and shock to give them both a new reality. But these lines are perhaps really more about raising the narrative tensions in the poem through rhetorical questions such as, “But who will come? And where from?” So up they climb. We don’t know why, but the atmosphere here is dripping with ill omen: they are “leaving a trail of blood, / leaving a trail of tears”. Then there is another of Lorca’s images yoking together unlikely items. As they climb to the roof-tiles, there is a trembling or quivering of “tiny tin-plate lanterns” and perhaps it’s this that becomes the sound of a “thousand crystal tambourines / [that] wound the break of day”. Lorca himself chose this image to comment on in his talk. He says if you ask why he wrote it he would tell you: “I saw them, in the hands of angels and trees, but I will not be able to say more; certainly I cannot explain their meaning”. I hear Andre Breton there, or Dali refusing to ‘explain’ the images of the truly surreal work. In each case the interpretative labour is handed over to us.

So up they climb. We don’t know why, but the atmosphere here is dripping with ill omen: they are “leaving a trail of blood, / leaving a trail of tears”. Then there is another of Lorca’s images yoking together unlikely items. As they climb to the roof-tiles, there is a trembling or quivering of “tiny tin-plate lanterns” and perhaps it’s this that becomes the sound of a “thousand crystal tambourines / [that] wound the break of day”. Lorca himself chose this image to comment on in his talk. He says if you ask why he wrote it he would tell you: “I saw them, in the hands of angels and trees, but I will not be able to say more; certainly I cannot explain their meaning”. I hear Andre Breton there, or Dali refusing to ‘explain’ the images of the truly surreal work. In each case the interpretative labour is handed over to us. Did they know this? It appears not. But who is she? Daughter? Lover? Both? Is this really what the two men find there? For sure, there is some mystery about the chronology because the seeming explanation of the killing is couched as a flashback: “The dark night grew intimate / as a cramped little square. / Drunken Civil Guards / were hammering at the door”. But Lorca often plays fast and loose with verb tenses. Was this earlier? Were they in search of the rebellious youth? But they found his girl-friend? Hanging her on the rooftop? Is the house owner her father? Does he know what has happened? Is this why his house is not his own anymore? Is this why he is no more what he was?

Did they know this? It appears not. But who is she? Daughter? Lover? Both? Is this really what the two men find there? For sure, there is some mystery about the chronology because the seeming explanation of the killing is couched as a flashback: “The dark night grew intimate / as a cramped little square. / Drunken Civil Guards / were hammering at the door”. But Lorca often plays fast and loose with verb tenses. Was this earlier? Were they in search of the rebellious youth? But they found his girl-friend? Hanging her on the rooftop? Is the house owner her father? Does he know what has happened? Is this why his house is not his own anymore? Is this why he is no more what he was? The only certain thing is that the poem does not reply. It ends with a recurrence of that opening yearning – now it’s read as a more obviously grieving voice – though it’s not necessarily to be read as the young man’s voice. It’s the ballad voice, the one I took so long to really grasp in Lorca’s work. It is a voice involved and passionate but with wider geographical, political and historical horizons beyond the individual incident. Like Auden’s ploughman in ‘Musee des Beaux Arts’, glimpsing Icarus’ fall from the sky, yet he must get on with his work, ‘Sleepingwalking Ballad’ returns us in its final lines to the wider world:

The only certain thing is that the poem does not reply. It ends with a recurrence of that opening yearning – now it’s read as a more obviously grieving voice – though it’s not necessarily to be read as the young man’s voice. It’s the ballad voice, the one I took so long to really grasp in Lorca’s work. It is a voice involved and passionate but with wider geographical, political and historical horizons beyond the individual incident. Like Auden’s ploughman in ‘Musee des Beaux Arts’, glimpsing Icarus’ fall from the sky, yet he must get on with his work, ‘Sleepingwalking Ballad’ returns us in its final lines to the wider world:

I really didn’t know it at the time, but the song’s words are, of course, by W.B. Yeats. It is his poem ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’, from The Wind Among the Reeds (1899).

I really didn’t know it at the time, but the song’s words are, of course, by W.B. Yeats. It is his poem ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’, from The Wind Among the Reeds (1899). I have now translated a number of Lorca’s poems and one of the great difficulties is to carry over such metaphorical leaps into English where they risk sounding very silly indeed. Fair enough, the alligator is, on the face of it, obvious enough: its gaping jaws give a good jolt of comic hyperbole to his image. But it’s still surprising in the context of a be-suited, bespectacled lecture hall in Spain. There is an exoticism there on the verge of surrealism and is characteristic of Lorca’s images. This search for novelty in image is clear when he argues later that a real poet must “shoot his arrows at living metaphors and not at the contrived and false ones which surround him”.

I have now translated a number of Lorca’s poems and one of the great difficulties is to carry over such metaphorical leaps into English where they risk sounding very silly indeed. Fair enough, the alligator is, on the face of it, obvious enough: its gaping jaws give a good jolt of comic hyperbole to his image. But it’s still surprising in the context of a be-suited, bespectacled lecture hall in Spain. There is an exoticism there on the verge of surrealism and is characteristic of Lorca’s images. This search for novelty in image is clear when he argues later that a real poet must “shoot his arrows at living metaphors and not at the contrived and false ones which surround him”.

Just one last detail from this great poem. Juan Antonio de Montilla is killed in the fight and – in one of Lorca’s characteristic jump cut edits (more of that in a minute) suddenly (it seems) the “judge and Civil Guard / come through the olive groves”. Somebody – a participant, one of the old women? – gives them an account of events in the form of exactly one of Lorca’s startling metaphors. This may have been a quarrel over a card game, or a girl, like so many others, but Lorca dizzyingly elevates it into an historical, even epic context:

Just one last detail from this great poem. Juan Antonio de Montilla is killed in the fight and – in one of Lorca’s characteristic jump cut edits (more of that in a minute) suddenly (it seems) the “judge and Civil Guard / come through the olive groves”. Somebody – a participant, one of the old women? – gives them an account of events in the form of exactly one of Lorca’s startling metaphors. This may have been a quarrel over a card game, or a girl, like so many others, but Lorca dizzyingly elevates it into an historical, even epic context:

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

The gateway to Richard Scott’s carefully structured first book is one of the most conventional poems in it. It’s a carefully punctuated, unrhymed sonnet. It is carefully placed (Public Library) and dated (1998). It’s the kind of poem and confinement Scott has fought to escape from and perhaps records the moment when that escape began: “In the library [. . .] there is not one gay poem, / not even Cavafy eyeing his grappa-sozzled lads”. The young Scott (I’ll come back to the biographical/authenticity question in a moment) takes an old copy of the Golden Treasury of Verse and writes COCK in the margin, then further obscene scrawls and doodles including, ironically a “biro-boy [who] rubs his hard-on against the body of a // sonnet”. Yet his literary vandalism leads to a new way of reading as – echoing the ideas of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – the narrator suddenly sees the “queer subtext” beneath many of the ‘straight’ poems till he is picking up a highlighter pen and “rimming each delicate / stanza in cerulean, illuminating the readers-to-come . . .”

You will have gathered that one of Power’s things is to mix English and Austrian German. This happens several times in ‘A Tour of Shrines of Upper Austria’ (though in this book we only get 7 parts of the full sequence). An observer stops at various shrine sites, jotting down some thoughts and taking a picture or two. Nothing is developed though Power’s poems do show an interest in religion on several other occasions. ‘The Moving Swan’ opens with a centre-justified prose description of candles flickering in a cathedral and another poem is drawn to the grave of two goats, observing: “two heaps of ivy/straw / one unlit red tealight”. And ‘Epiphany Night’ is a more extended series of notes recording a local celebration with bells, dressing-up, boats, lanterns. This is all observed in loosely irregular lines by the narrator from her “wohnung” (apartment). To wring all engagement or emotional or imaginative response from such a text is, I suppose, quite an achievement but to spend 70-odd pages in such company really is wearisome.

You will have gathered that one of Power’s things is to mix English and Austrian German. This happens several times in ‘A Tour of Shrines of Upper Austria’ (though in this book we only get 7 parts of the full sequence). An observer stops at various shrine sites, jotting down some thoughts and taking a picture or two. Nothing is developed though Power’s poems do show an interest in religion on several other occasions. ‘The Moving Swan’ opens with a centre-justified prose description of candles flickering in a cathedral and another poem is drawn to the grave of two goats, observing: “two heaps of ivy/straw / one unlit red tealight”. And ‘Epiphany Night’ is a more extended series of notes recording a local celebration with bells, dressing-up, boats, lanterns. This is all observed in loosely irregular lines by the narrator from her “wohnung” (apartment). To wring all engagement or emotional or imaginative response from such a text is, I suppose, quite an achievement but to spend 70-odd pages in such company really is wearisome.