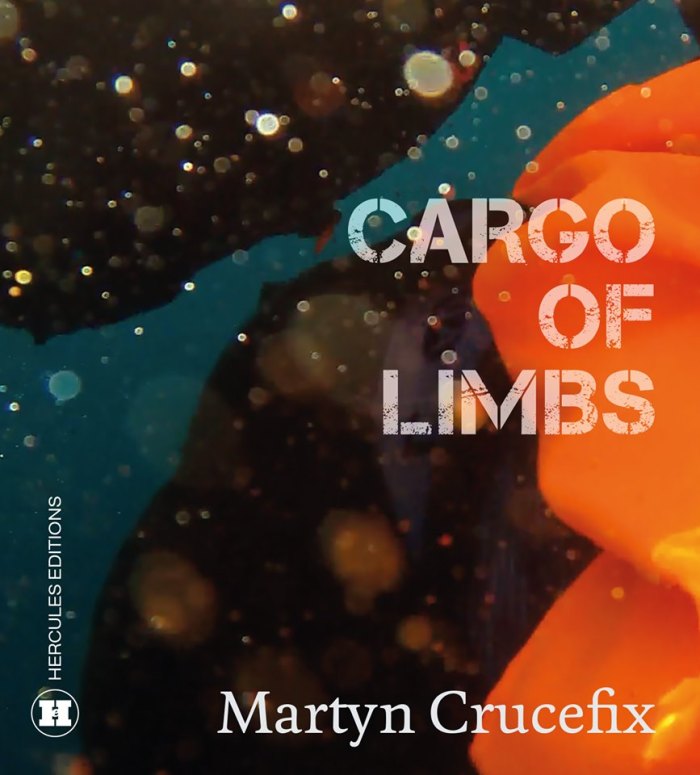

I was recently tagged in a social media post by someone doing the Sealey Challenge – one poetry book a day for the month of August! I do admire people’s stamina. I was tagged because the book of the day for this person – and a mercifully short one at that – turned out to be my own chapbook, published by Hercules Editions back in 2019 under the title Cargo of Limbs. Originating in events almost 10 years ago now, it is utterly depressing that the longish poem that constitutes most of the book remains relevant. Now – as then – the news is full of people in small boats. Then, refugees and migrants were embarking in the Mediterranean. Now, most of the talk here is of people embarking from the coast of France to risk the real dangers of the English Channel. The book remains in print and can be bought from Hercules here or by contacting me directly.

I posted a short piece about the chapbook during the Covid lockdown in April 2020. I was preoccupied then with what writers can/cannot do in such dire circumstances as pandemics and wars: ‘Beyond feeling helpless, what do writers do in a crisis? I think of Shelley hearing news of the Manchester Massacre from his seclusion in Italy in 1822; Whitman’s close-up hospital journals and poems during the American Civil War; Edward Thomas hearing grass rustling on his helmet in the trenches near Ficheux; Ahkmatova’s painfully clear-sighted stoicism in Leningrad in the 1930s; MacNeice’s montage of “neither final nor balanced” thoughts in his Autumn Journal of 1938; Carolyn Forche witnessing events in 1970s El Salvador; Heaney’s re-location and reinvention of himself as “an inner émigré, grown long-haired / And thoughtful” in 1975; Brian Turner’s raw responses to his experience as a US soldier in Iraq in 2003′. You can read more of that piece – and hear me read the opening of the poem – here.

In the chapbook I wrote a ‘How I Wrote the Poem’ type of discussion and it’s that that I felt would be worth posting in full here because, though times have changed, nothing seems very different about the refugee crisis and the moral issues surrounding it . . .

It’s early in 2016 and I am on a train crossing southern England. On my headphones, Ian McKellen is reading Seamus Heaney’s just-published translation of Book 6 of Virgil’s Aeneid. This is the book in which Aeneas journeys into the Underworld. As he descends, he encounters terror, war and violence before the house of the dead. He finds a tree filled with “[f]alse dreams”, then grotesque beasts, centaurs, gorgons, harpies. At the river Acheron, he sees crowds of people thronging towards a boat. These people are desperate to cross, yet the ferryman, Charon, only allows some to embark, rejecting others. At this point, in Heaney’s translation, Aeneas cries out to his Sibyl guide: “What does it mean [. . . ] / This push to the riverbank? What do these souls desire? / What decides that one group is held back, another / Rowed across the muddy waters?”

The timing is crucial. I’m listening to these powerful words in March 2016 and, rather than the banks of the Acheron and the spirits of the dead, they conjure up the distant Mediterranean coastline I’m seeing every day on my TV screen: desperate people fleeing their war-torn countries. The timing is crucial. It’s just six months since the terrible images of Alan Kurdi’s body – drowned on the beach near Bodrum, Turkey – had filled the media. In the summer of 2015, this three-year-old Syrian boy of Kurdish origins and his family had fled the war engulfing Syria. They hoped to join relatives in the safety of Canada and were part of the historic movement of refugees from the Middle East to Europe at that time. In the early hours of September 2nd, the family crowded onto a small inflatable boat on a Turkish beach. After only a few minutes of their planned flight across the Aegean, the dinghy capsized. Alan, his older brother, Ghalib, and his mother, Rihanna, were all drowned. They joined more than 3,600 other refugees who died in the eastern Mediterranean that year.

Beyond my train window, the fields of England swept past; Virgil’s poem continued to evoke the journeys of refugees such as the Kurdi family. It struck me that some form of versioning of these ancient lines might be a way of addressing – as a poet – such difficult, contemporary events. I hoped they might offer a means of support as Tony Harrison has spoken of using rhyme and metre to negotiate, to pass through the “fire” of painful material. I also saw a further aspect to these dove-tailing elements that interested me: the power of the image. The death of Alan Kurdi made the headlines because photographs of his drowned body, washed up on the beach, had been taken. When Nilüfer Demir, a Turkish photographer for the Dogan News Agency, arrived on the beach that day, she said it was like a “children’s graveyard”. She took pictures of Alan’s lifeless body; a child’s body washed up along the shore, half in the sand and half in the water, his trainers still on his feet. Demir’s photographs, shared by Peter Bouckaert of Human Rights Watch on social media, became world news.

Demir’s images were indeed shocking, breaking established, unspoken conventions about showing the bodies of dead children. I remember passionate online debates about the rights and wrongs of disseminating such images. Yet the power of the images, without doubt, contributed to a shift in opinion, marked to some degree by a shift in language as those people moving towards Europe came to be termed “refugees” more often than the othering word, “migrants”. This tension between the desire to draw attention to suffering and the risks of exploitation has arisen more recently. In June 2019, the hull of a rusty fishing boat arrived in Venice to form part of an installation at the Biennale by the artist, Christoph Buchel. The vessel had foundered off the Italian island of Lampedusa in April 2015 with 700 people aboard. They too were refugees seeking a better life. Only 28 people survived. When the Italian authorities recovered the vessel in 2016 there were 300 bodies still trapped inside. Buchel called his exhibit Barca Nostra (Our Boat) and there is little doubting his (and the Biennale organisers’) good intentions to raise public awareness of the continuing plight of refugees travelling across the Mediterranean. Yet Lorenzo Tondo, for example, has argued that Buchel’s exhibit diminishes, even exploits, the suffering of those who died, “losing any sense of political denunciation, transforming it into a piece [of art] in which provocation prevails over the goal of sensitising the viewer’s mind” (The Observer, 12.05.19).

Interestingly, in Book 6, Virgil asks the Gods to strengthen his resolve to report back the horrifying truths he’s about to witness and I came to realise that the narrative voice in my new version ought to be the voice of a witnessing photojournalist. It is this narrator who accompanies my Aeneas (renamed Andras) through a more contemporary ‘underworld’. I imagine Andras also as a journalist, though he is a man of words rather than images. At some distance now from the writing of the poem, I see that the two western journalists have differing reactions to what they encounter. The photographer holds firm to recording events with a distanced objectivity. He considers it his role, his duty, to deliver such truths (perhaps as Nilüfer Demir felt on the beach at Bodrum; perhaps as Amel El Zakout felt on her own harrowing journey from Istanbul in 2015, the extraordinary images of which accompany this poem). My photographer’s partner, Andras, has a lot less poem-time, yet – following the outline of Virgil’s poem closely – he has a more emotional, empathetic response. By turns, he is fearful and compassionate. I think he has more moral scruple. As well as presenting the plight of contemporary refugees, between them I hope they are also debating, in part, the role of any artist impelled to bear witness to the suffering of others.

So Virgil’s original lines provided guidance but I have changed some things. As I have said, early on he apostrophises the Gods, asking for assistance in accurately reporting his journey to the Underworld. I saw no justification for my own narrator to be appealing to divine powers, though he understands those people fleeing might well put their trust in their own God. So it’s with tongue in cheek that he asks to be allowed to “file” his work in a way that is accurate (“what / happens is what’s true”) and these lines become his moment to make his faith in objectivity clear: “let me file // untroubled as I’m able”. The “brother” he alludes to is one-time journalist, Ernest Hemingway, who would often risk gunfire to file his despatches in Madrid, during the Spanish Civil War.

Later, Virgil describes the journey of Aeneas and the Sibyl through an ill-lit landscape, drained of colour, approaching the jaws of Hell. All around are personifications of Grief, Care, Disease, Old Age, Fear, Hunger, War and Death itself (Heaney’s translation buries these personifications to a large degree; in general, I prefer Allen Mandelbaum’s 1961 translation). I wanted to retain the device of personification but shifted the physical contexts of the actions to evoke the kind of experiences refugees are still fleeing from: bombing, persecution, the use of chemical weapons (“yellow dust of poison breeze running // into the trunks of trees” – an image I have borrowed from Choman Hardi’s fine poem ‘Gas Attack’). Aeneas then discovers “a giant shaded elm” (tr. Mandelbaum). Heaney’s translation associates this with “False dreams”; Mandelbaum has “empty Dreams”. All around the tree are grotesque beasts (centaurs, gorgons, harpies) which frighten Aeneas and he draws his sword against them. In my version, the tree of false dreams becomes an image of the often vain hopes that drive people to flee their homes, while Virgil’s menagerie of beasts suggest the kinds of distortions, the physical and mental lengths to which such people are driven and the dangers they face in such extremities: “bestialised women // girls groomed to new shape”. It’s here my Andras reveals his more volatile emotional nature in fearing what he sees, thinking these figures may be a threat to him. In the original, it is the Sibyl who calms Aeneas; in my version it is the less emotionally engaged narrator/photojournalist who lends Andras the defence of more emotional “distance”.

Virgil’s Aeneas begins to descend towards the River Acheron and the “squalid ferryman”, Charon. The landscape of my version is a portrait of routes overland to the sea’s edge and my figure of Charon, “the guardian of the crossing”, becomes an inscrutable and unscrupulous people smuggler. Virgil makes it clear he is aged, “but old age in a god is tough and green”. I took this hint of ambiguity further in terms of Charon’s eyes, his outstretched hand, even his physical appearance and presence: “young and attentive / yet from the choppy tide / he’s older gazing / a while then—ah— // gone—”. Virgil describes the “multitude” rushing eagerly to Charon’s boat and makes use of two epic similes comparing the human figures to falling autumn leaves and flocks of migrating birds. I’ve kept the ghosts of these images and extended the people’s approach to the ferryman as an opportunity to describe the kinds of perilous vessels that since 2015 have been launched into the Mediterranean: “they long to stagger // into the dinghy’s wet mouth / the oil-stinking holds / where shuttered waters / pool”. Virgil’s Charon permits some to board but bars others. As Book 6 proceeds, it is made clear those who are rejected are the dead who remain as yet unburied. In my version, the people smuggler also retains the power to choose who travels, but his reasons for doing so are not clear (probably money, possibly caprice). The irony is that in not permitting some to embark he may also be saving lives.

In Virgil’s poem, before he hears the full explanation of Charon’s selection process, Aeneas is baffled and deeply moved by it. He cries out – this time in Mandelbaum’s translation – for an explanation to the guiding Sibyl: “by what rule / must some keep off the bank while others sweep / the blue-black waters with their oars?” I wanted my Andras to be equally moved by their plight and the seeming injustice. But the question he tries to articulate is directed not merely at those who make a living from such dangerous journeys but also (I hope) to those in more official, political, public capacities – those who represent us – who also possess the power to accept or deny entry to people fleeing for their lives. There is no Virgilian equivalent to my final five lines but I wanted to accentuate the growing disparity between the ways the two western journalists are responding to what they witness. The narrator still wants to take good images. But Andras is moved enough to see the need for less distance, to dash the camera to the ground, to engage with those who are fleeing, to try to help.

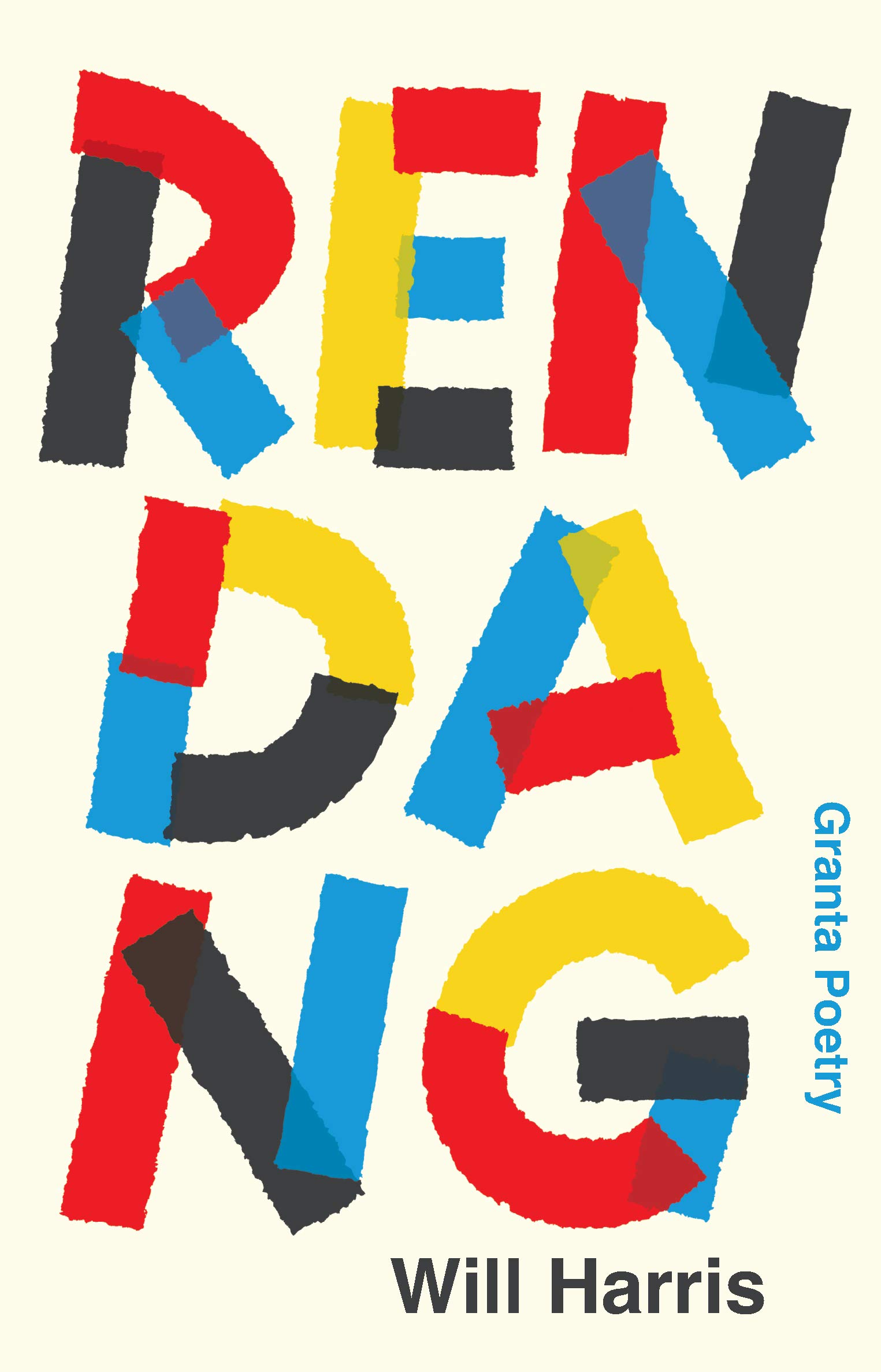

At the heart of Will Harris’ first collection is the near pun between ‘rendang’ and ‘rending’. The first term is a spicy meat dish, originating from West Sumatra, the country of Harris’ paternal grandmother, a dish traditionally served at ceremonial occasions to honour guests. In one of many self-reflexive moments, Harris imagines talking to the pages of his own book, saying “RENDANG”, but their response is, “No, no”. The dish perhaps represents a cultural and familial connectiveness that has long since been severed, subject to a process of rending, and the best poems here take this deracinated state as a given. They are voiced by a young, Anglo-Indonesian man, living in London and though there is a strong undertow of loss and distance, through techniques such as counterpoint, cataloguing and compilation, the impact of the book, if not exactly of sweetness, is of human contact and discourse, of warmth, of “something new” being made.

At the heart of Will Harris’ first collection is the near pun between ‘rendang’ and ‘rending’. The first term is a spicy meat dish, originating from West Sumatra, the country of Harris’ paternal grandmother, a dish traditionally served at ceremonial occasions to honour guests. In one of many self-reflexive moments, Harris imagines talking to the pages of his own book, saying “RENDANG”, but their response is, “No, no”. The dish perhaps represents a cultural and familial connectiveness that has long since been severed, subject to a process of rending, and the best poems here take this deracinated state as a given. They are voiced by a young, Anglo-Indonesian man, living in London and though there is a strong undertow of loss and distance, through techniques such as counterpoint, cataloguing and compilation, the impact of the book, if not exactly of sweetness, is of human contact and discourse, of warmth, of “something new” being made. This last phrase comes from ‘State-Building’, one of the more interesting, earlier poems in Rendang (a book which feels curiously hesitant and experimental in its first 42 pages, then bursts into full voice from its third section onwards). This poem characteristically draws very diverse topics together, starting from Derek Walcott’s observations on love (his image is of a broken vase which is all the stronger for having been reassembled). This thought leads to seeing a black figure vase in the British Museum which takes the poem (in a Keatsian moment, imagining what’s not represented there) to thoughts of “freeborn” men debating philosophy and propolis, or bee glue, metaphorically something that has to come “before – is crucial for – the building of a state”. The bees lead the narrator’s fluent thoughts to a humming bin bag, then a passing stranger who reminds the narrator of his grandmother and the familial connection takes him to his own father, at work repairing a vase, a process (like the poem we have just read) of assemblage using literal and metaphorical “putty, spit, glue” to bring forth, not sweetness, but in a slightly cloying rhyme, that “something new”.

This last phrase comes from ‘State-Building’, one of the more interesting, earlier poems in Rendang (a book which feels curiously hesitant and experimental in its first 42 pages, then bursts into full voice from its third section onwards). This poem characteristically draws very diverse topics together, starting from Derek Walcott’s observations on love (his image is of a broken vase which is all the stronger for having been reassembled). This thought leads to seeing a black figure vase in the British Museum which takes the poem (in a Keatsian moment, imagining what’s not represented there) to thoughts of “freeborn” men debating philosophy and propolis, or bee glue, metaphorically something that has to come “before – is crucial for – the building of a state”. The bees lead the narrator’s fluent thoughts to a humming bin bag, then a passing stranger who reminds the narrator of his grandmother and the familial connection takes him to his own father, at work repairing a vase, a process (like the poem we have just read) of assemblage using literal and metaphorical “putty, spit, glue” to bring forth, not sweetness, but in a slightly cloying rhyme, that “something new”.

I

I In lieu of a new blog post, here is a link to the Hercules Editions webpage on which I have formulated a few thoughts about the current lockdown, photography and the (forgotten?) refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. It is a piece in part related to the Hercules publication of my longer poem,

In lieu of a new blog post, here is a link to the Hercules Editions webpage on which I have formulated a few thoughts about the current lockdown, photography and the (forgotten?) refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. It is a piece in part related to the Hercules publication of my longer poem,

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood

It’s interesting then – in The Republic of Motherhood The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

The mother in the poem also suffers postpartum depression and Berry seems here to allude to experiences of First World war soldiers, wounded, repaired and sent back out to fight again, without fundamental issues being addressed: “when I was well they gave me my pram again / so I could stare at the daffodils in the parks of Motherhood”. She ends up haunting cemeteries, both real and symbolic, and it is here she finds even more tragic victims of motherhood, of birth trauma and of psychosis. The final response of the poem is to pray – though it is a prayer that has scant sense of religion but combines empathy with other women with a great anger expressed in the phrase “the whole wild fucking queendom [of Motherhood]”. The paradoxically inextricable sorrow and beauty of motherhood becomes the subject of the rest of the pamphlet, but this poem ends with the mother echoing a baby’s “nightcry” and erasing her own self, “sunlight pixellating my face”. The poem’s rawness is unresolved. Having crossed the border into motherhood (that decision is never questioned here), the contradictory pulls of Motherhood (capital M) and the stresses of mothering (small m) have a devastating impact. In a recent poem called ‘The Suburbs’ – Berry’s contribution to the National Poetry Competition 40th Anniversary Anthology – she records the effect of mothering even more starkly: “my world miniaturised”.

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

But such optimism is not a frequent note. Most of the remaining poems deal with the experience of depression in motherhood. ‘Early’ is almost as happy as it gets with mother and child now like “new sweethearts, / awake through the shining hours, close as spoons in the polishing cloth of dawn” (what a glorious image that is). But even here there are demands from the child that will need “forgiving” by the mother. One of these concerns her role as writer, particularly the difficulty of writing in the maelstrom of mothering: “every line I wanted to write for you / seems already written, read / and forgotten”. And this is why Berry chooses to co-opt lines from Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s terrifying story, The Yellow Wallpaper in ‘The Yellow Curtains’. Both texts can be read as studies of postpartum depression, but the despair has as much to do with the women as writers, confined, and – as in Gillman – the husband voices the demands and expectations of convention, of queendom: “He said [. . .] I must / take care of myself. For his sake.”

In the summer of 2018, John Greening spent 2 weeks as artist-in-residence at the Heinrich Boll cottage in Dugort, Achill Island. The resulting

In the summer of 2018, John Greening spent 2 weeks as artist-in-residence at the Heinrich Boll cottage in Dugort, Achill Island. The resulting

![DM-HkzHWkAAx8CG[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/dm-hkzhwkaax8cg1.jpg)

![laocoon[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/laocoon1.jpg)

![8226eece-e840-4378-9fb4-cd24af13aef4[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/8226eece-e840-4378-9fb4-cd24af13aef41.jpg)

![DLRftRFW4AAtwJQ[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/dlrftrfw4aatwjq1.jpg)

![making-ends-meet-cover[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/making-ends-meet-cover1.jpg)

![182712359-a2163bed-2fd9-4910-9e04-673d2bb611ef[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/182712359-a2163bed-2fd9-4910-9e04-673d2bb611ef1.jpg)