This review first appeared in Acumen Poetry Magazine in the autumn of 2025. Many thanks to the reviews editor, Andrew Geary, for commissioning it.

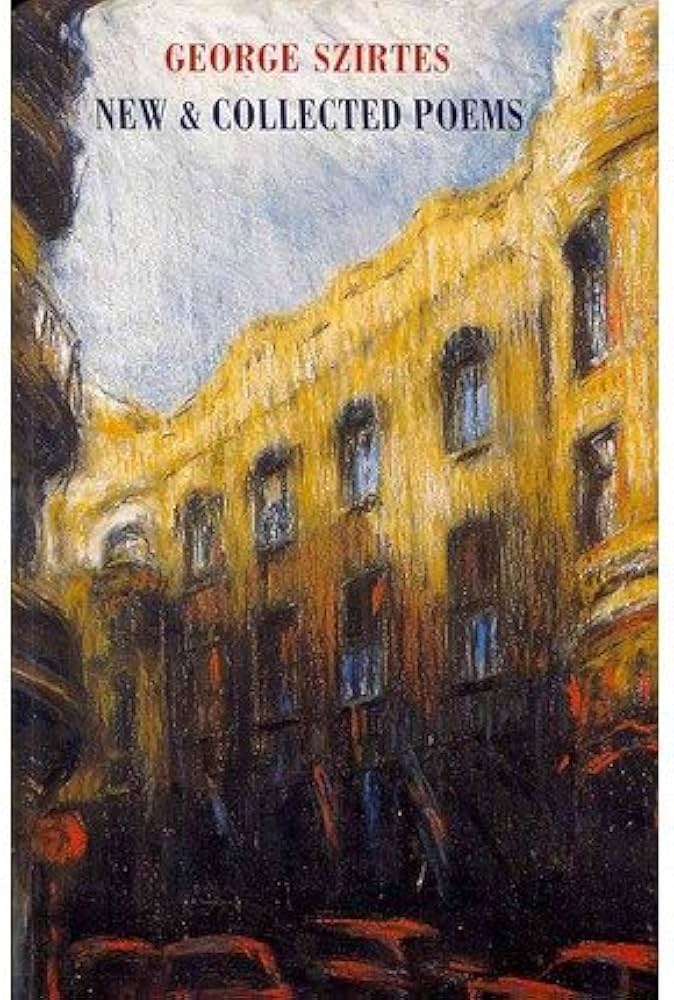

As a female writer, talented in a variety of genres, living in a difficult political climate, Hungarian born Krisztina Tóth shares a good deal with Huch (my review of Tim Adès translation of Huch’s final book was posted here). Coming to the fore around the revolutionary year, 1989, Tóth has written poetry, children’s books, fiction, drama and musicals. My Secret Life (Bloodaxe Books, 2025) is her first sole author publication in English, ably translated and introduced by George Szirtes, presenting an overview of her poetry from 2001 to the present. Szirtes tells us that Tóth is no longer living in Hungary because of unbearable frictions with the Orbán regime. Like Huch she is drawn to poetry as personal expression, often to the formal elements of the art, both perhaps offering a redoubt against values she finds unacceptable. If there is little redemption to be found in her poems, there is some consolation to be had through the twin imperatives she expresses, to remain compassionate and to persist in trying to articulate human experience. Neither goal is easy.

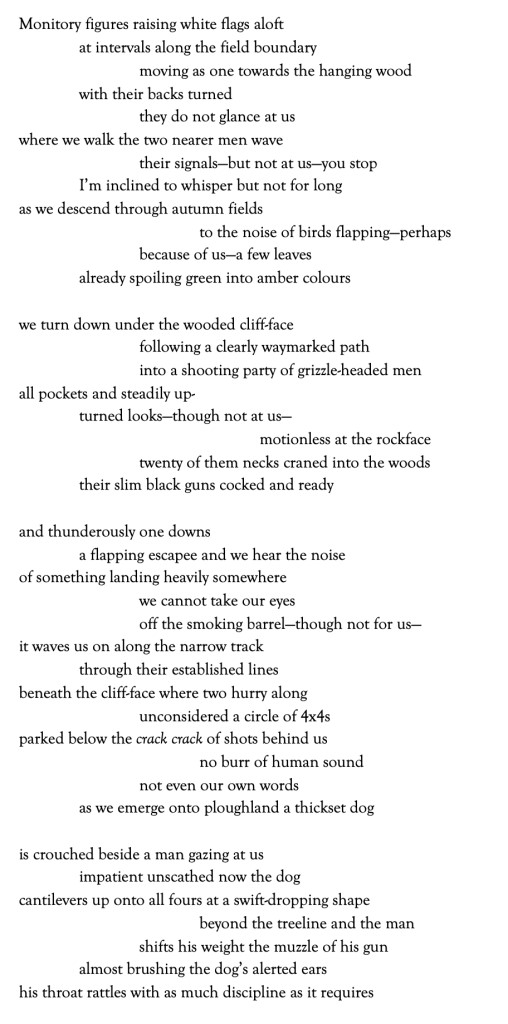

Szirtes argues Tóth’s style is conversational, plain, precise, offering ‘a kind of kitchen-sink realism’. The personal also features and in these self-selected poems we get glimpses of a barely affectionate mother, a father who dies young, children, lovers, and a difficult grandmother. It’s not clear if these are genuinely autobiographical portraits and, anyway, they are most often absorbed into Tóth’s emblematic writing. An example would be ‘Barrier’ in which a couple are crossing a bridge, seemingly discussing ending their relationship. With the river below and trams thundering past, ‘the pavement was juddering’ and the poem is really about this instability in relationships as much as the (social/political) world, concluding there were ‘certain matters that couldn’t be finalised’. Such uncertainty drives roots even into the self: ‘I’m somebody else today or simply elsewhere’ (‘Send me a Smile’). Tóth uses the image of the ‘professional tourist’ in one of the major poems included here. With little background given, the narrator visits town after town, apparently hoping to be joined by a ‘you’ who never appears. Obviously a ‘stranger’, she wanders aimlessly, haplessly, buys a few things, the poem inconclusively ending with an image of a used toothbrush, ‘like an angry old punk, / its face turned to the tiles, / its white bristles stiff with paste’ (‘Tourist’).

Alienation, expressed through a profound sense of homelessness, is Tóth’s real subject. With the irony turned up to 11, the poem ‘Homeward’ ends quizzically, ‘But where’s home?’ In such a world view, the ability to remain compassionate is important to the poet, however hard it may be. The painfully brilliant ‘Dog’ presents a couple driving at night, seeing a badly injured dog at the roadside, and the woman wants the man to stop. I think they do, but the poem’s focus is on the powerful impetus to help versus the powerful sense that whatever can be done will prove futile. More weirdly, in ‘Duration’, the narrator finds a Mermaid Barbie doll stuck in the ground outside her flat. The childhood associations, the vulnerability of the frail figure, seem to compel action, but ‘what’?

Should I pull the thing out of the ground so it

sheds earth every night, because however often

we wash it, or wrap it in a tissue or leave it

on the radiator we’ll only have to bin it in the end?

Tóth’s wry, highly original lament, on deciding not to buy a universal plug adaptor, perhaps suggests what is being wished for in many of these poems. It is a way for a feeling human being to feel more at home in a world of suffering: ‘how to adapt the world / and its gizmos to the pounding of so many hearts’.

‘Song of the Secret Life’ pulls together many of these strands with the life as much the inner life of the self (the heart) as the life kept hidden in an unsympathetic personal or political environment. In the case of an artist, it is also the creative life, and as much ‘an utter mystery, a puzzle undone’, to the writer herself. But in order ‘to survive it needs telling’ and – like Huch’s creative figure in ‘The Poet’ – even if current conditions do not welcome such efforts, the individual must continue to write, to use language, to affirm the validity of the individual viewpoint. This is the burden of the magnificently hypnotic long concluding poem, ‘Rainy Summer’, in which the long-lined, rhymed couplets, express an unrelenting haunting of the speaker by ‘a sentence’. The latter phrase opens many of the lines, and it goes talking, throbbing, pulsing, dancing and rushing through the poem itself, though as much as the sentence might prove to be some sort of ‘home’ we are never told what it expresses. This is largely because it is a ‘rhythmic unit without words’, it is ‘the bodiless body of language’, it is the ‘speech that knows no speech’, it is ‘a sentence that contained you, gone yet here, some of each’.

Szirtes’ emphasis on the political backdrop to Tóth’s poems might lead us to expect more obvious political engagement and subject matter. That’s not what we get here, though no doubt her surroundings have determined many aspects of the work. Hers is a profound voice, finding in the menace, alienation, and instability around her emblems of more universally shared experiences of rootlessness, troubled self-questioning, of sensibilities that find the world as it is a painful and difficult place to navigate, of the pull of pity and compassion versus an overwhelming sense of the futility of individual action. ‘Sleeper’ addresses what might be a transmigrating soul or spirit, a ‘little pulse box’, asking question after question about where it has been, what it has seen, the mysterious passage from life to death, or vice versa: ‘what’s it like to step into such cold, unlit fiefdoms, / does anything remain’? Tóth’s poems ask such questions and like the best modern poems offer us equivocal answers only, consolatory but not redemptive.

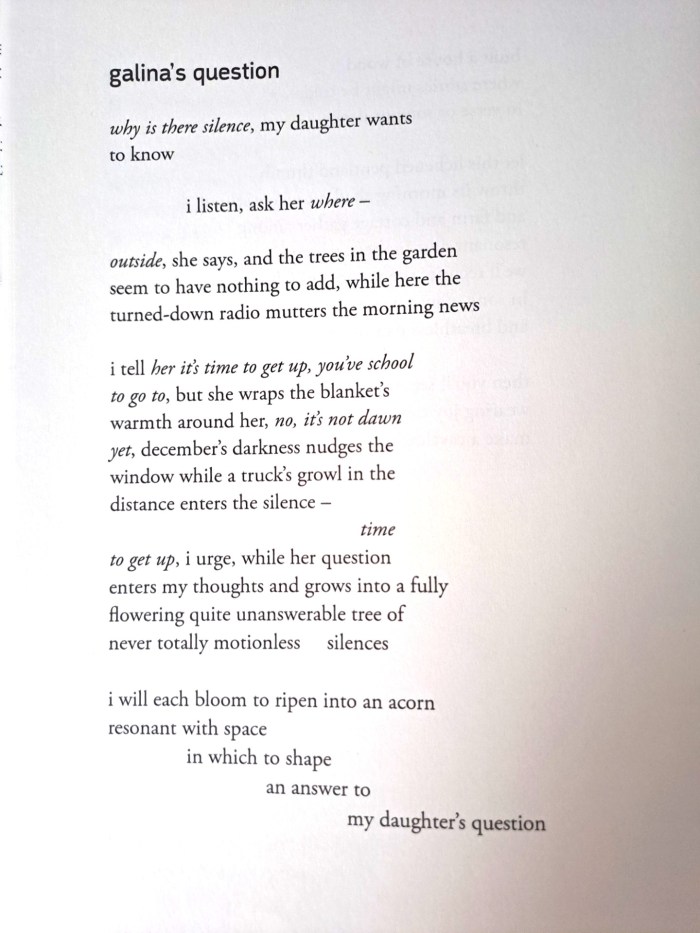

Here is the whole of one poem included here:

Where – Kristina Toth, tr. George Szirtes

Not there, on the tight bend of the paved highway,

where cars are occasionally prone to skidding,

chiefly in winter, though no one dies there,

x

not there where streets are greener and leafier

where lawns are mowed and there’s a dog in the garden

and the head of the family gets home late at night,

x

nor there in front of the school where every morning

a man is waiting regular as clockwork,

nor inside the gates on the concrete playground,

x

nor in the neglected, dehydrated meadow

where a discarded dog-end hits the ground and glows

for a moment, it doesn’t begin there

x

but at the edge of the forest, in rotting humus

where somebody once was buried alive,

that’s where the poem begins.