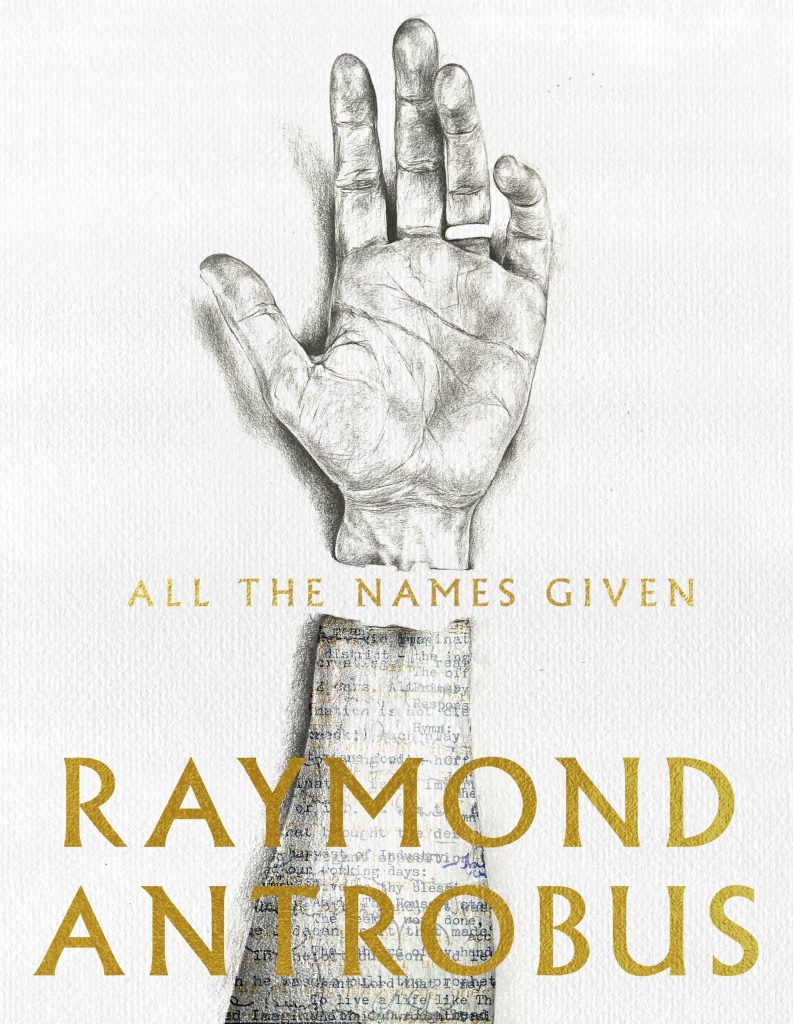

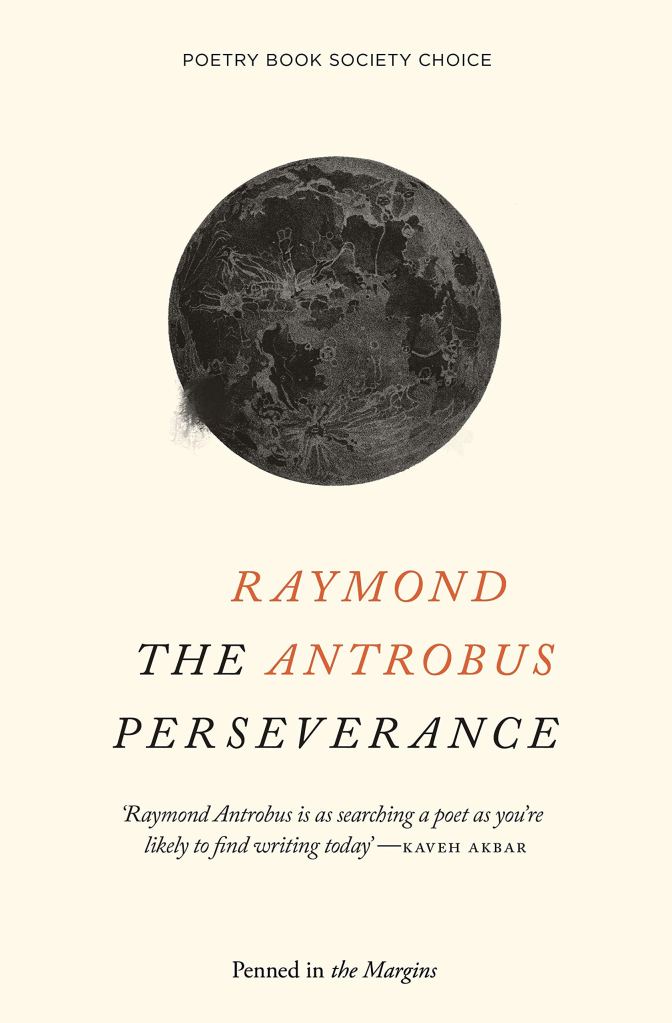

Genuinely acclaimed first books can be hard to follow up. Raymond Antrobus’ The Perseverance (Penned in the Margins, 2018) was a Poetry Book Society Choice and won the Ted Hughes Award and the Rathbone’s Folio Prize in 2019. I reviewed the book that year as one of the five collections shortlisted for the Forward Felix Dennis First Collection Prize. In many ways it was a conventional book of poems – its voice was colloquial, it successfully employed a range of (now) traditional forms (dramatic monologues, prose poem, sestina, ghazal, pantoum), its syntax and punctuation were nothing out of the ordinary. Its subject matter was to a large extent dominated by a son’s difficult relationship with his father, by questions of racial identity and (this is what made it especially distinctive) the experience of a young Deaf man. Besides the latter, what really marked the book out (I argued) was ‘that impossible-to-teach, impossible-to-fake, not especially ultra-modern quality of compassion’. Listen to Raymond Antrobus talking about his first collection here.

Now several years on and literary acclaim, a new publisher (this book is published by Picador Poetry – Penned in the Margins has since sadly ceased operations), a recent marriage and a broadening of perspective (particularly towards the USA) all place Antrobus in a very different environment. He has set aside a lot of the experimentation with recognised forms (which is not to say the new poems do not experiment with poetic form) and the book opens very positively:

Give thanks to the wheels touching tarmac at JFK,

give thanks to the latches, handles, what we squeeze

x

into cabins, the wobbling wings, the arrivals,

departures, the long line at the gates, the nerves held,

x

give thanks to the hand returning the passport [. . .]

In a similar tone, ‘The Acceptance’ concludes with the word ‘Welcome’ being signed. But the 30 lines preceding this hark back to that ‘complicated man’ (a phrase from ‘Dementia’, from The Perseverance), the poet’s father. Though dead for several years now, he continues to haunt his son’s dreams and a number of these new poems. In ‘Every Black Man’, the ‘dark dreadlocked Jamaican father’ meets his prospective, English mother-in-law for the first time. He’s already drunk, there is shouting, he lashes out, she racially insults him: they never meet in the same room again. The father’s ‘heartless sense of humour’ is turned into a slow blues: ‘I think that’s how he handled pain, drink his only tutor’ (‘Heartless Humour Blues’). And the man’s ‘complication’ is reaffirmed in the poem, ‘Arose’, in which, talking to his embarrassed son, the father boasts of the great sex had with the boy’s mother, but then is touchingly remembered, calling out her name: ‘Rose? And he said it like something in him / grew towards the light.’

But All The Names Given also pays more fulsome tribute to Antrobus’ mother. In ‘Her Taste’, despite her conventional, English, religious background, she drops out, joins a circus (literally, I think!), has various relationships, and eventually gets pregnant by Seymour, the ‘complicated man’ from Jamaica, who left her to raise the children. Thirty years on, she’s defiant, independent, ‘holding her head higher at seventy’. We see her leafing through a scrapbook of her past, ‘rolling a spliff on somebody’s balcony’ or again, ‘in church reading Bertrand Russell’s ‘Why I’m Not a Christian’.’ Despite such moments, the maternal portrait does not quite possess the vivid distinctiveness of the paternal one. But, with the benefit of the passing years, Antrobus can now write, ‘On Being A Son’, in which he unreservedly praises Rose in her neediness, her self-sufficiency, her helplessness with IT, her helpfulness in so much else. He concludes, channelling her voice: ‘mother / dyes her hair, / don’t say greying / say sea salt / and cream’.

This greater focus on the mother is partly a redressing of the previous book’s gender imbalance, but it is also at one with Antrobus’ interest in family and heritage as offering clues to his own identity. It turns out the Antrobus name – from his mother’s English side – is anciently English (or far distantly Norse) and associated with Antrobus in Cheshire. ‘Antrobus or Land of Angels’ records a visit (by mother and son) to the place, to face the suspicious looks in The Antrobus Arms, the guard dogs at the Hall:

A farmer appears, asks if we’re descended

from Edmund Antrobus.

x

Sir Edmund Antrobus, (3rd baronet)

slaver, beloved father,

over-seer, owner of plantations

x

in Jamaica, British Guiana and St Kitts.

The son’s quick denial of the line of descent is a complex moment. Despite carrying the same name, his mother is not truly a descendant. But given His Lordship’s slave-owning history, who is to say whether there is any genetic relation, ironically, through his Jamaican-born father, Seymour. The thought surfaces in ‘Horror Scene as Black English Royal (Captioned)’. Antrobus’ note tells us this poem was sparked by tabloid/CNN speculations in 2019 about the likely ‘blackness’ of the Sussexes’ royal baby. The poem’s narrator looks down at his own hands and sees ‘your great-great-great Grandfather’s owner’s hands’.

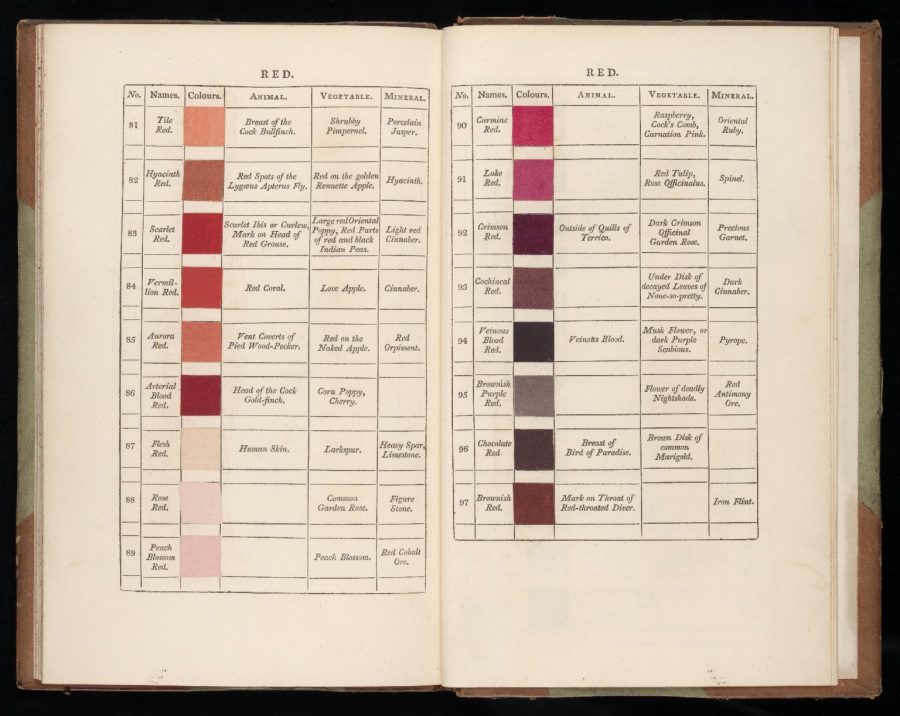

So All The Names Given quickly reveals itself to be a book deeply troubled by the kinds of questions raised in the poem ‘Plantation Paint’: ‘Why am I like this? // What am I like? / Who does / it matter to?’ In this second book, Antrobus is still working towards an ‘overstanding’. The idea was alluded to in The Perseverance via a Peter Tosh lyric: ‘love is the man overstanding’. It is a form of understanding that emerges after all untruths have been overcome. The truths, untruths and complications of identity preoccupy the majority of these new poems. Only occasionally does Antrobus set aside such profound (perhaps irresolvable) anxieties. The African/Vietnamese waitress in ‘A Short Speech Written on Receipts’ is a figure who seems to outweigh the poet’s wrangling over his own selfhood, leading him to wonder: ‘Maybe kindness is how / you take down the stalls’. The gates of compassion also open frankly and to great effect in ‘At Every Edge’ and ‘A Paper Shrine’, two brief poems remembering very different students in creative writing classes. Likewise, ‘For Tyrone Givans’, commemorates a young Deaf man (a friend and contemporary of Antrobus) who committed suicide in Pentonville Prison in 2018. Here too, the vector of attention is outwards, towards Tyrone’s mistreatment by the authorities, his suffering and despair, rather than inwards towards the poet’s own ‘complications’:

Tyrone, the last time I saw you alive

I’d dropped my pen

on the staircase

x

didn’t hear it fall but you saw and ran

down to get it, handed it to me

before disappearing, said,

x

you might need this.

This review was originally commisioned and published by The High Window

Nina Mingya Powles’ collection, Magnolia 木蘭, is an uneven book of great energy, of striking originality, but also of a great deal of borrowing. This is what good debut collections used to be like! I’m reminded of Glyn Maxwell’s disarming observation in On Poetry (Oberon Books, 2012) that he “had absolutely nothing to say till [he] was about thirty-four”. The originality of Magnolia 木蘭 is largely derived from Powles’ background and brief biographical journey. She is of mixed Malaysian-Chinese heritage, born and raised in New Zealand, spending a couple of years as a student in Shanghai and now living in the UK. Her subjects are language/s, exile and displacement, cultural loss/assimilation and identity. Shanghai is the setting for most of the poems here and behind them all loiter the shadows and models of

Nina Mingya Powles’ collection, Magnolia 木蘭, is an uneven book of great energy, of striking originality, but also of a great deal of borrowing. This is what good debut collections used to be like! I’m reminded of Glyn Maxwell’s disarming observation in On Poetry (Oberon Books, 2012) that he “had absolutely nothing to say till [he] was about thirty-four”. The originality of Magnolia 木蘭 is largely derived from Powles’ background and brief biographical journey. She is of mixed Malaysian-Chinese heritage, born and raised in New Zealand, spending a couple of years as a student in Shanghai and now living in the UK. Her subjects are language/s, exile and displacement, cultural loss/assimilation and identity. Shanghai is the setting for most of the poems here and behind them all loiter the shadows and models of

I don’t think the intriguing glimpses of an individual young woman in this first poem are much developed in later ones. The Mulan figure makes a couple of other appearances in the book and is reprised in the concluding poem, ‘Magnolia, jade orchid, she-wolf’. This consists of even shorter prose observations. In Chinese, ‘mulan’ means magnolia so the fragments here cover the plant family Magnoliaceae, the film again, the Chinese characters for mulan, Shanghai moments, school days back in New Zealand and Adeline Yen Mah’s Chinese Cinderella. It’s hard not to think you are reading much the same poem, using similar techniques, though this one ends more strongly: “My mouth a river in full bloom”.

I don’t think the intriguing glimpses of an individual young woman in this first poem are much developed in later ones. The Mulan figure makes a couple of other appearances in the book and is reprised in the concluding poem, ‘Magnolia, jade orchid, she-wolf’. This consists of even shorter prose observations. In Chinese, ‘mulan’ means magnolia so the fragments here cover the plant family Magnoliaceae, the film again, the Chinese characters for mulan, Shanghai moments, school days back in New Zealand and Adeline Yen Mah’s Chinese Cinderella. It’s hard not to think you are reading much the same poem, using similar techniques, though this one ends more strongly: “My mouth a river in full bloom”. Unlike Carson’s use of fragmentary texts, Powles is less convincing and often gives the impression of casting around for links. This is intended to reflect a sense of rootlessness (cultural, racial, personal) but there is a willed quality to the composition. One of the things Powles does have to say (thinking again of Maxwell’s observation) is the doubting of what is dream and what is real. The prose piece, ‘Miyazaki bloom’, opens with this idea and the narrator’s sense of belonging “nowhere” is repeated. This is undoubtedly heartfelt – though students living in strange cities have often felt the same way. Powles also casts around for role models (beyond Mulan) and writes about the New Zealand poet, Robin Hyde and the great Chinese author Eileen Chang, both of whom resided in Shanghai for a time. ‘Falling City’ is a rather exhausting 32 section prose exploration of Chang’s residence, mixing academic observations, personal reminiscence and moments of fantasy to end (bathetically) with inspiration for Powles: “I sit down at one of the café tables and begin to write. It is the first day of spring”.

Unlike Carson’s use of fragmentary texts, Powles is less convincing and often gives the impression of casting around for links. This is intended to reflect a sense of rootlessness (cultural, racial, personal) but there is a willed quality to the composition. One of the things Powles does have to say (thinking again of Maxwell’s observation) is the doubting of what is dream and what is real. The prose piece, ‘Miyazaki bloom’, opens with this idea and the narrator’s sense of belonging “nowhere” is repeated. This is undoubtedly heartfelt – though students living in strange cities have often felt the same way. Powles also casts around for role models (beyond Mulan) and writes about the New Zealand poet, Robin Hyde and the great Chinese author Eileen Chang, both of whom resided in Shanghai for a time. ‘Falling City’ is a rather exhausting 32 section prose exploration of Chang’s residence, mixing academic observations, personal reminiscence and moments of fantasy to end (bathetically) with inspiration for Powles: “I sit down at one of the café tables and begin to write. It is the first day of spring”.

At the heart of Will Harris’ first collection is the near pun between ‘rendang’ and ‘rending’. The first term is a spicy meat dish, originating from West Sumatra, the country of Harris’ paternal grandmother, a dish traditionally served at ceremonial occasions to honour guests. In one of many self-reflexive moments, Harris imagines talking to the pages of his own book, saying “RENDANG”, but their response is, “No, no”. The dish perhaps represents a cultural and familial connectiveness that has long since been severed, subject to a process of rending, and the best poems here take this deracinated state as a given. They are voiced by a young, Anglo-Indonesian man, living in London and though there is a strong undertow of loss and distance, through techniques such as counterpoint, cataloguing and compilation, the impact of the book, if not exactly of sweetness, is of human contact and discourse, of warmth, of “something new” being made.

At the heart of Will Harris’ first collection is the near pun between ‘rendang’ and ‘rending’. The first term is a spicy meat dish, originating from West Sumatra, the country of Harris’ paternal grandmother, a dish traditionally served at ceremonial occasions to honour guests. In one of many self-reflexive moments, Harris imagines talking to the pages of his own book, saying “RENDANG”, but their response is, “No, no”. The dish perhaps represents a cultural and familial connectiveness that has long since been severed, subject to a process of rending, and the best poems here take this deracinated state as a given. They are voiced by a young, Anglo-Indonesian man, living in London and though there is a strong undertow of loss and distance, through techniques such as counterpoint, cataloguing and compilation, the impact of the book, if not exactly of sweetness, is of human contact and discourse, of warmth, of “something new” being made. This last phrase comes from ‘State-Building’, one of the more interesting, earlier poems in Rendang (a book which feels curiously hesitant and experimental in its first 42 pages, then bursts into full voice from its third section onwards). This poem characteristically draws very diverse topics together, starting from Derek Walcott’s observations on love (his image is of a broken vase which is all the stronger for having been reassembled). This thought leads to seeing a black figure vase in the British Museum which takes the poem (in a Keatsian moment, imagining what’s not represented there) to thoughts of “freeborn” men debating philosophy and propolis, or bee glue, metaphorically something that has to come “before – is crucial for – the building of a state”. The bees lead the narrator’s fluent thoughts to a humming bin bag, then a passing stranger who reminds the narrator of his grandmother and the familial connection takes him to his own father, at work repairing a vase, a process (like the poem we have just read) of assemblage using literal and metaphorical “putty, spit, glue” to bring forth, not sweetness, but in a slightly cloying rhyme, that “something new”.

This last phrase comes from ‘State-Building’, one of the more interesting, earlier poems in Rendang (a book which feels curiously hesitant and experimental in its first 42 pages, then bursts into full voice from its third section onwards). This poem characteristically draws very diverse topics together, starting from Derek Walcott’s observations on love (his image is of a broken vase which is all the stronger for having been reassembled). This thought leads to seeing a black figure vase in the British Museum which takes the poem (in a Keatsian moment, imagining what’s not represented there) to thoughts of “freeborn” men debating philosophy and propolis, or bee glue, metaphorically something that has to come “before – is crucial for – the building of a state”. The bees lead the narrator’s fluent thoughts to a humming bin bag, then a passing stranger who reminds the narrator of his grandmother and the familial connection takes him to his own father, at work repairing a vase, a process (like the poem we have just read) of assemblage using literal and metaphorical “putty, spit, glue” to bring forth, not sweetness, but in a slightly cloying rhyme, that “something new”.

Ella Frears’ Shine, Darling is brimming with youthful exuberance and despair, yet not a jot lacking in thoughtful sophistication. Her subjects are boredom, sex, a woman’s body and the harassment that rushes to fill the void left by uncertain selfhood. A key poem is ‘The (Little) Death of the Author’, about a 13-year-old girl texting/sexting boys in her class, though the title is, of course, one Roland Barthes would have enjoyed. The narrator – looking back to her teen self – remembers pretending to be texting in the bath. The “triumph” is to make the boys think of herself naked (when she’s really eating dinner or doing homework). Hence “Text / and context are different things”. Her texts are careful constructions, evocative, alluring, full of tempting ellipses. On both sides, there is a filmic fictionalising going on (in the absence of any real sexual experience). The poem (which is a cleverly achieved irregularly lined sestina) ends with the authorial voice breaking cover: the poem itself is “a text I continue to send: Reader, I’m in the bath . . . / Nothing more to say than that. And if you like / you can join me”. The flirtation is a bit overdone (but other poems show Frears is wholly conscious of that) and the poem indicates one of this book’s chief concerns is with the difference between the truth of what happens and the truth of a poem.

Ella Frears’ Shine, Darling is brimming with youthful exuberance and despair, yet not a jot lacking in thoughtful sophistication. Her subjects are boredom, sex, a woman’s body and the harassment that rushes to fill the void left by uncertain selfhood. A key poem is ‘The (Little) Death of the Author’, about a 13-year-old girl texting/sexting boys in her class, though the title is, of course, one Roland Barthes would have enjoyed. The narrator – looking back to her teen self – remembers pretending to be texting in the bath. The “triumph” is to make the boys think of herself naked (when she’s really eating dinner or doing homework). Hence “Text / and context are different things”. Her texts are careful constructions, evocative, alluring, full of tempting ellipses. On both sides, there is a filmic fictionalising going on (in the absence of any real sexual experience). The poem (which is a cleverly achieved irregularly lined sestina) ends with the authorial voice breaking cover: the poem itself is “a text I continue to send: Reader, I’m in the bath . . . / Nothing more to say than that. And if you like / you can join me”. The flirtation is a bit overdone (but other poems show Frears is wholly conscious of that) and the poem indicates one of this book’s chief concerns is with the difference between the truth of what happens and the truth of a poem.

The obvious risk of such sexual adventuring is the subject of ‘Hayle Services (grease impregnated)’. The parenthetical allusion here is to Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘Filling Station’ where everything is “oil-soaked, oil-permeated [. . .] grease / impregnated”, a poem which concludes, against the odds of its grimy context, that “Somebody loves us all”. In contrast, Frears’ crappy, retail-dominated English motorway service station is (ironically) the stage for a pregnancy scare, a desperate search for a test kit in Boots and an anxious, “[p]issy” fumbling in the M&S toilet cubicle, then waiting for the “pink voila”. The headlong, impossible-to-focus, sordid anxiety here is brilliantly captured in the short, run-on lines. Frears also catches the young woman’s multiplicity of streams of consciousness, the scattershot: the potential father is present but soon forgotten, his reassurances dismissed, the pushy sales staff avoided in anger and embarrassment, the difficulty of urinating, the cringingly inappropriate joke-against-self in “et tu uterus”, the conventional moral judgement (“soiled / ruined spoiled”) and the final phone call to “Mamma, can you come pick me up?”

The obvious risk of such sexual adventuring is the subject of ‘Hayle Services (grease impregnated)’. The parenthetical allusion here is to Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘Filling Station’ where everything is “oil-soaked, oil-permeated [. . .] grease / impregnated”, a poem which concludes, against the odds of its grimy context, that “Somebody loves us all”. In contrast, Frears’ crappy, retail-dominated English motorway service station is (ironically) the stage for a pregnancy scare, a desperate search for a test kit in Boots and an anxious, “[p]issy” fumbling in the M&S toilet cubicle, then waiting for the “pink voila”. The headlong, impossible-to-focus, sordid anxiety here is brilliantly captured in the short, run-on lines. Frears also catches the young woman’s multiplicity of streams of consciousness, the scattershot: the potential father is present but soon forgotten, his reassurances dismissed, the pushy sales staff avoided in anger and embarrassment, the difficulty of urinating, the cringingly inappropriate joke-against-self in “et tu uterus”, the conventional moral judgement (“soiled / ruined spoiled”) and the final phone call to “Mamma, can you come pick me up?”

And yet, poems in Shine, Darling do regularly turn to the moon for possible explanations of actions (‘Phases of the Moon / Things I Have Done’), for a witness if not for protection (‘Walking Home One Night’) and for directions (‘I Knew Which Direction’). The latter poem is a beautiful lyric opener to the book but is rather misleading. The repetition of the word “moonlight” seems to give an almost visionary access: “no longer a word but a colour and then a feeling / and then the thing itself”. It is curious that a poet asserts the transparency of language in this way (Frears is not much concerned with the nature, limits and impositions of language, unlike Nina Mingya Powles’ shortlisted Magnolia 木蘭), but also the idea of such an untrammelled access to “the thing itself” is countered by every poem that follows. Frears’ world view may not be too much troubled by words but the very idea of a unitary truth to be beheld with clarity is profoundly doubted.

And yet, poems in Shine, Darling do regularly turn to the moon for possible explanations of actions (‘Phases of the Moon / Things I Have Done’), for a witness if not for protection (‘Walking Home One Night’) and for directions (‘I Knew Which Direction’). The latter poem is a beautiful lyric opener to the book but is rather misleading. The repetition of the word “moonlight” seems to give an almost visionary access: “no longer a word but a colour and then a feeling / and then the thing itself”. It is curious that a poet asserts the transparency of language in this way (Frears is not much concerned with the nature, limits and impositions of language, unlike Nina Mingya Powles’ shortlisted Magnolia 木蘭), but also the idea of such an untrammelled access to “the thing itself” is countered by every poem that follows. Frears’ world view may not be too much troubled by words but the very idea of a unitary truth to be beheld with clarity is profoundly doubted.

I’m not proud to admit that Way More Than Luck passed me by when it was first published. As you are probably aware, Wilkinson reviews poetry regularly for The Guardian, and he’s very familiar on social media as a poet and critic, a distance runner and a passionate Liverpool football fan. But the book’s cover (Dalglish, I think), its title and some of the publicity persuaded me that the football bit was going to be predominant. It’s certainly an almost unique aspect of the collection, but it turns out the debilitating darkness of psychological depression is an even more significant one. Wilkinson signals this concern via the book’s two epigraphs. One is about the nature of depression

I’m not proud to admit that Way More Than Luck passed me by when it was first published. As you are probably aware, Wilkinson reviews poetry regularly for The Guardian, and he’s very familiar on social media as a poet and critic, a distance runner and a passionate Liverpool football fan. But the book’s cover (Dalglish, I think), its title and some of the publicity persuaded me that the football bit was going to be predominant. It’s certainly an almost unique aspect of the collection, but it turns out the debilitating darkness of psychological depression is an even more significant one. Wilkinson signals this concern via the book’s two epigraphs. One is about the nature of depression

For me, it’s these psychological truths that Wilkinson is so good at conveying. There are other poems later in the book (and perhaps ‘Stag’ is an elusive example) which begin to sketch episodes of a foundering romantic relationship and ‘Building a Brighter, More Secure Future’ is a very effective excursion into witty political satire (a skilfully handled sestina based on the Conservative Party election manifesto, 2015). And there are the football poems. They comprise the central sequence of 14 poems, introduced with a heart-felt Prologue that says what follows is for the ordinary football fans, written out of “a love beyond the smear campaigns, / the media’s hooligans”. A large part of what Wilkinson has in mind here is the shocking response in parts of the media to the Hillsborough tragedy in 1989, when 96 men, women and children died (David Cain’s Forward prize shortlisted book, Truth Street, from Smokestack Books, movingly dealt with this event and the media and policing responses and

For me, it’s these psychological truths that Wilkinson is so good at conveying. There are other poems later in the book (and perhaps ‘Stag’ is an elusive example) which begin to sketch episodes of a foundering romantic relationship and ‘Building a Brighter, More Secure Future’ is a very effective excursion into witty political satire (a skilfully handled sestina based on the Conservative Party election manifesto, 2015). And there are the football poems. They comprise the central sequence of 14 poems, introduced with a heart-felt Prologue that says what follows is for the ordinary football fans, written out of “a love beyond the smear campaigns, / the media’s hooligans”. A large part of what Wilkinson has in mind here is the shocking response in parts of the media to the Hillsborough tragedy in 1989, when 96 men, women and children died (David Cain’s Forward prize shortlisted book, Truth Street, from Smokestack Books, movingly dealt with this event and the media and policing responses and  But the poems also show how difficult it is to escape the miasma of cliché that seems to engulf football itself. Anfield is filled with a “fabled buzz”, then “the place erupt[s]”. Barnes unleashes a “a sweeping, goal-bound ball”, and a particular game offers one “last-ditch twist”. I’m reminded of Louis MacNeice’s observation (now sadly compromised in various ways, but the spirit of it remains valid, I think) that he wanted a poet not to be “too esoteric. I would have a poet able-bodied [sic], fond of talking, a reader of the newspapers, capable of pity and laughter, informed in economics, appreciative of women [sic], involved in personal relationships, actively interested in politics, susceptible to physical impressions’. There are many more of these poets around these days and to bring (even) football into the purview of poetry can hardly be a bad thing. Yet it is not an easy one and there may be some risks in deciding to headline the attempt. Ian Duhig’s blurb note to Way More Than Luck has gingerly to negotiate this issue: “The beautiful game inspires some beautiful poems in Ben Wilkinson’s terrific debut collection … but there’s far more than football to focus on here”. Yes, indeed.

But the poems also show how difficult it is to escape the miasma of cliché that seems to engulf football itself. Anfield is filled with a “fabled buzz”, then “the place erupt[s]”. Barnes unleashes a “a sweeping, goal-bound ball”, and a particular game offers one “last-ditch twist”. I’m reminded of Louis MacNeice’s observation (now sadly compromised in various ways, but the spirit of it remains valid, I think) that he wanted a poet not to be “too esoteric. I would have a poet able-bodied [sic], fond of talking, a reader of the newspapers, capable of pity and laughter, informed in economics, appreciative of women [sic], involved in personal relationships, actively interested in politics, susceptible to physical impressions’. There are many more of these poets around these days and to bring (even) football into the purview of poetry can hardly be a bad thing. Yet it is not an easy one and there may be some risks in deciding to headline the attempt. Ian Duhig’s blurb note to Way More Than Luck has gingerly to negotiate this issue: “The beautiful game inspires some beautiful poems in Ben Wilkinson’s terrific debut collection … but there’s far more than football to focus on here”. Yes, indeed.

But Surge itself has since gone through various forms. There were 10 original poems written quickly in 2016. There was a performance piece (at London’s Roundhouse) in the summer of 2017 (it was this version that won the Ted Hughes Award for New Work in poetry in 2017). But it has taken 3 years for this Chatto book to be finalised. In an interview just last year, Bernard observed that they were still unclear what the “final structure” of the material would be. I’m possessed of no insider knowledge on this, but it looks as if this “final” version took some considerable effort – reading it makes me conscious of the strait-jacket that a conventional slim volume of poetry imposes – and I’m not sure the finalised 50-odd pages of the collection really act as the best foil for what are, without doubt, a series of stunningly powerful poems. The blurb and publicity present the book (as publishers so often do) as wholly focused on the New Cross and Grenfell fires but this isn’t really true and something is lost in including the more miscellaneous pieces, particularly towards the end of the book.

But Surge itself has since gone through various forms. There were 10 original poems written quickly in 2016. There was a performance piece (at London’s Roundhouse) in the summer of 2017 (it was this version that won the Ted Hughes Award for New Work in poetry in 2017). But it has taken 3 years for this Chatto book to be finalised. In an interview just last year, Bernard observed that they were still unclear what the “final structure” of the material would be. I’m possessed of no insider knowledge on this, but it looks as if this “final” version took some considerable effort – reading it makes me conscious of the strait-jacket that a conventional slim volume of poetry imposes – and I’m not sure the finalised 50-odd pages of the collection really act as the best foil for what are, without doubt, a series of stunningly powerful poems. The blurb and publicity present the book (as publishers so often do) as wholly focused on the New Cross and Grenfell fires but this isn’t really true and something is lost in including the more miscellaneous pieces, particularly towards the end of the book. Bernard’s poetic voice is at its best when making full use of the licence of free forms, broken grammar, infrequent punctuation, the colloquial voice and often incantatory patois. So a voice in ‘Harbour’ wanders across the page, hesitantly, uncertainly, till images of heat, choking and breaking glass make it clear this is someone caught in the New Cross Fire. Another voice in ‘Clearing’ watches, in the aftermath of the blaze, as an officer collect body parts (including the voice’s own body): “from the bag I watch his face turn away”. The cryptically titled ‘+’ and ‘–’ shift to broken, dialogic prose as a father is asked to identify his dead son through the clothes he was wearing. Then the son’s voice cries out for and watches his father come to the morgue to identify his body. This skilful voice throwing is a vivid way of portraying a variety of individuals and their grief. ‘Kitchen’ offers a calmer voice re-visiting her mother’s house, the details and familiarity evoking simple things that have been lost in the death of the child:

Bernard’s poetic voice is at its best when making full use of the licence of free forms, broken grammar, infrequent punctuation, the colloquial voice and often incantatory patois. So a voice in ‘Harbour’ wanders across the page, hesitantly, uncertainly, till images of heat, choking and breaking glass make it clear this is someone caught in the New Cross Fire. Another voice in ‘Clearing’ watches, in the aftermath of the blaze, as an officer collect body parts (including the voice’s own body): “from the bag I watch his face turn away”. The cryptically titled ‘+’ and ‘–’ shift to broken, dialogic prose as a father is asked to identify his dead son through the clothes he was wearing. Then the son’s voice cries out for and watches his father come to the morgue to identify his body. This skilful voice throwing is a vivid way of portraying a variety of individuals and their grief. ‘Kitchen’ offers a calmer voice re-visiting her mother’s house, the details and familiarity evoking simple things that have been lost in the death of the child: I’m guessing most of the poems I have referred to so far come from the early work of 2016. Other really strong pieces focus on events after the Fire itself. ‘Duppy’ is a sustained description – information slowly drip-fed – of a funeral or memorial meeting and it again becomes clear that the narrative voice is one of the dead: “No-one will tell me what happened to my body”. The title of the poem is a Jamaican word of African origin meaning spirit or ghost. ‘Stone’ is perhaps a rare recurrence of the author’s more autobiographical voice and in its scattered form and absence of punctuation reveals a tactful and beautiful lyrical gift as the narrator visits Fordham Park to sit beside the New Cross Fire’s memorial stone. ‘Songbook II’ is another chanted, hypnotic tribute to one of the mothers of the dead and is probably one of the poems Ali Smith is thinking of when she associates Bernard’s work with that of W.H. Auden.

I’m guessing most of the poems I have referred to so far come from the early work of 2016. Other really strong pieces focus on events after the Fire itself. ‘Duppy’ is a sustained description – information slowly drip-fed – of a funeral or memorial meeting and it again becomes clear that the narrative voice is one of the dead: “No-one will tell me what happened to my body”. The title of the poem is a Jamaican word of African origin meaning spirit or ghost. ‘Stone’ is perhaps a rare recurrence of the author’s more autobiographical voice and in its scattered form and absence of punctuation reveals a tactful and beautiful lyrical gift as the narrator visits Fordham Park to sit beside the New Cross Fire’s memorial stone. ‘Songbook II’ is another chanted, hypnotic tribute to one of the mothers of the dead and is probably one of the poems Ali Smith is thinking of when she associates Bernard’s work with that of W.H. Auden. But when the device of haunting and haunted voices is abandoned, Bernard’s work drifts quickly towards the literal and succumbs to the pressure to record events and places (the downside of the archival instinct). A tribute to Naomi Hersi, a black trans-woman found murdered in 2018, sadly doesn’t get much beyond plain location, a kind of reportage and admission that it is difficult to articulate feelings (‘Pem-People’). There are interesting pieces which read as autobiography – a childhood holiday in Jamaica, joining a Pride march, a sexual encounter in Camberwell, but on their own behalf Bernard seems curiously to have lost their eagle eye for the selection of telling details and tone and tension flatten out:

But when the device of haunting and haunted voices is abandoned, Bernard’s work drifts quickly towards the literal and succumbs to the pressure to record events and places (the downside of the archival instinct). A tribute to Naomi Hersi, a black trans-woman found murdered in 2018, sadly doesn’t get much beyond plain location, a kind of reportage and admission that it is difficult to articulate feelings (‘Pem-People’). There are interesting pieces which read as autobiography – a childhood holiday in Jamaica, joining a Pride march, a sexual encounter in Camberwell, but on their own behalf Bernard seems curiously to have lost their eagle eye for the selection of telling details and tone and tension flatten out: The mirroring architectonic of the collection emerges with the poems written about the Grenfell Tower fire. So we have ‘Ark II’, two pools of prose broken by slashes which seem to be fed by too many tributary streams: the silent marches in Ladbroke grove, the Michael Smithyman murder and abandoned investigation, Smithyman’s transition to Michelle, and the burning of the Grenfell Tower effigy, the video of which emerged in 2018.

The mirroring architectonic of the collection emerges with the poems written about the Grenfell Tower fire. So we have ‘Ark II’, two pools of prose broken by slashes which seem to be fed by too many tributary streams: the silent marches in Ladbroke grove, the Michael Smithyman murder and abandoned investigation, Smithyman’s transition to Michelle, and the burning of the Grenfell Tower effigy, the video of which emerged in 2018.