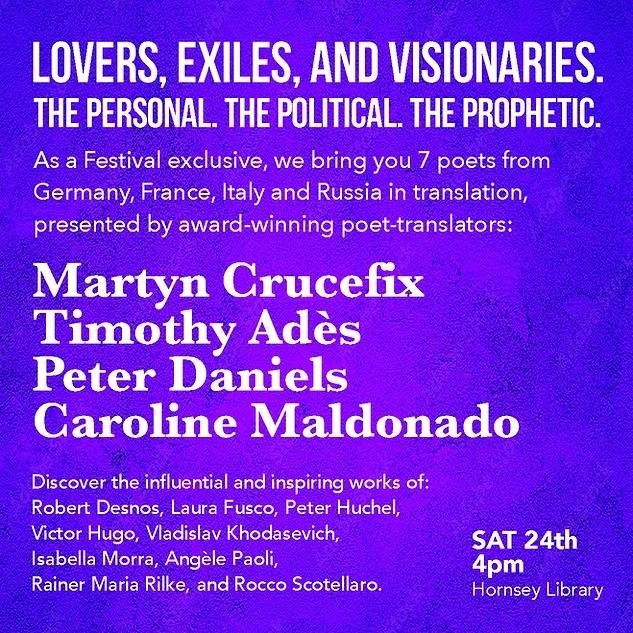

Rather late notice – not wholly down to my own tardiness – but I will be reading work in translation at the inaugural Crouch End Literary Festival this weekend. Do come along if you can. There are plenty of other events scheduled in the Festival, but this one is at 4pm on Saturday 24th February in the Gallery upstairs at the Hornsey Library Haringey Park, London N8 9JA (see map on location and how to get there). The event is free to attend and as you’ll see I am reading alongside poet/translator friends Timothy Ades, Caroline Maldonado and Peter Daniels. The poster, left, is not wholly accurate as I’ll be reading work by Rilke (Pushkin Press) and Peter Huchel (Shearsman Books) and not from my translations of Angele Paoli (that chapbook has been delayed at present). Tim will be reading from his Robert Desnos (Arc) and Victor Hugo; Peter is reading from his Vladislav Khodasevich and Caroline will (I think) be reading from her Smokestack books of work by Scotellaro and Laura Fusco.

Here are more details about the 4 of us:

Timothy Adès is a rhyming translator-poet with awards for, among others, the French poets – Victor Hugo (1802-1885) and Robert Desnos (1900-1945). Both were enormously prolific and engaged passionately with the issues of their times. Timothy is a much-praised translator with further published books from Spanish, French, and (coming soon) the German of Ricarda Huch. He runs a bookstall of translated poetry and is a member of the Royal Society of Literature and a Trustee of Agenda poetry magazine. His translations have won the John Dryden prize and the TLS Premio Valle Inclán prize. Find him on Facebook and YouTube and his website is http://www.timothyades.com

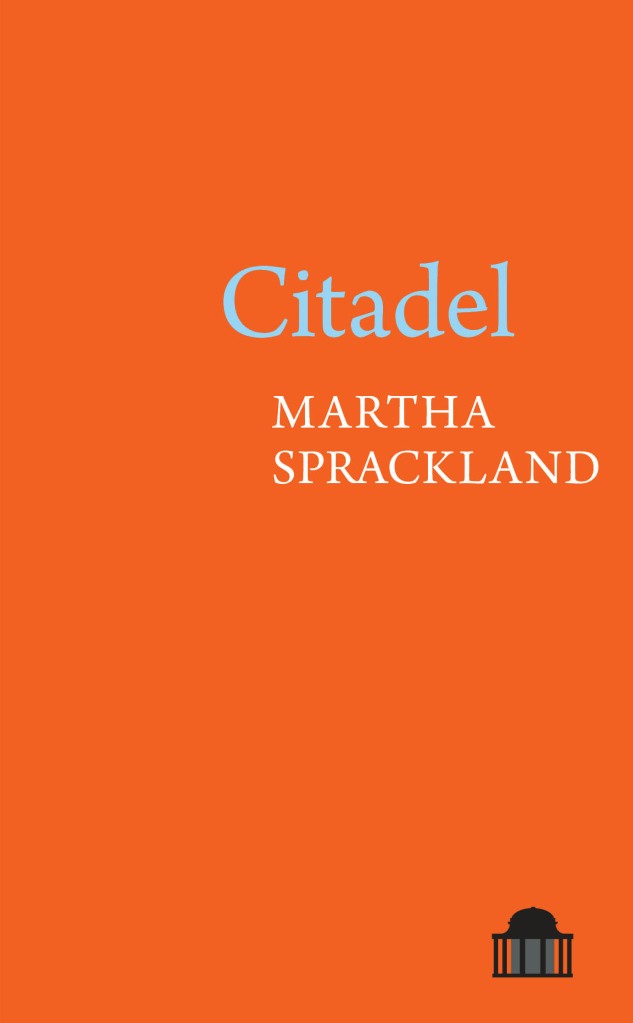

Martyn Crucefix is the author of seven original collections of poetry, most recently Between a Drowning Man (Salt, 2023) and Cargo of Limbs (Hercules Editions, 2019). Awards include an Eric Gregory award, a Hawthornden Fellowship, and the Schlegel-Tieck Prize for translations (from the German) of the poems of Peter Huchel. His translation of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies (Enitharmon, 2006) was shortlisted for the Popescu Prize for Poetry Translation. A major Rilke selected poems, Change Your Life, will be published by Pushkin Press in 2024. Till recently a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at The British Library, he also edits the Acumen Poetry Magazine Young Poets web page. Website at http://www.martyncrucefix.com

Peter Daniels’ most recent original books of poetry are Old Men (forthcoming, Salt 2024) and My Tin Watermelon (Salt, 2019). His acclaimed translations from the Russian of Vladislav Khodasevich appeared in 2023 from Angel Classics and was a Poetry Book Society Recommended Translation. Other publications include Counting Eggs (Mulfran Press, 2012) and the pamphlets Mr. Luczinski Makes a Move (HappenStance, 2011) and The Ballad of Captain Rigby (Personal Pronoun, 2013). Peter has won first prizes in the 2010 TLS Poetry Competition, the 2010 Ver Poets Competition, the 2008 Arvon competition, the 2002 Ledbury competition, and has twice been a winner in the Poetry Business pamphlet competition. Website at https://www.peterdaniels.org.uk

Caroline Maldonado is a poet and translator living in London and Italy. She has worked in community regeneration, in law centres and with migrants and refugees in London. She chaired the Board of Trustees of Modern Poetry in Translation until 2016. Publications of her own work include the pamphlet What they say in Avenale (Indigo Dreams Publishing, 2014) and a full collection Faultlines (Vole Books, 2022). Translations include Isabella (Smokestack Books, 2019). Other translations (all published by Smokestack Books) are poems by Rocco Scotellaro, Your call keeps us awake (2013), co-translated with Allen Prowle, and two collections of poems by Laura Fusco: Liminal (2020), which received a PEN (UK) Translates award, and Nadir (2022). More at http://www.poetrypf.co.uk/carolinemaldonadobiog.shtml