In the light of recent political events in the UK, it seemed important to be thinking about wider perspectives this week – Europe, Revolutions, the role of poetry. The poems of Vladislav Kodasevich came easily to mind and I have wanted to praise Peter Daniels’ translations of them for a while now.

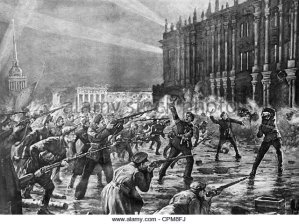

What emerges from Peter Daniels’ Vladislav Khodasevich: Selected Poems (Angel Classics, 2013) is a vivid picture of a poet who was, both by temperament and historical circumstance, very much an individual. From a Lithuanian Polish background, coming to creativity at the fag end of Symbolism, witnessing Russia’s revolutionary year of 1917, going into permanent exile in 1922, Khodasevich (1886-1939) was perhaps inevitably a writer with little sense of belonging, of sure identity. It’s no surprise that he plays with images of doubles, often standing outside himself, then counters such doubts with rather grandiose claims to his poetic vocation.

The consequent difficulty of pigeon-holing him as a poet is one of the reasons why he is less well-known than his more familiar contemporaries – Mandelshtam, Akhmatova, Tsvetayeva and Pasternak. He is also difficult to pin down because he is “a modernist, but with a classical temperament” (Daniels’ Preface). In a period when others were tearing up rule books (poetical and political) Khodasevich harks back to the “eight little volumes” of Pushkin’s works. Amongst the ruck of Symbolists, Acmeists, Futurists and Cubo-Futurists, Khodasevich’s poems mostly retain traditional forms and he proudly declares: “I grafted the classic rose / to the Soviet briar bush” (‘Petersburg’). Such formalism presents great challenges for the translator, of course, with Khodasevich flaunting his conservative and poetic concerns – “O may my last expiring groan / be wrapped inside an articulate ode!” – and, like many before and since, he argues such formal frameworks are paradoxically the way to find release. (Carol Rumens has discussed some formal aspects of a Daniels/Khodasevich poem for The Guardian). Curiously, his last ever poem was in praise of the iambic tetrameter, the classic metre of the Russian tradition:

Its nature is mysterious,

where spondee sleeps and paeon sings,

one law is held within it – freedom.

Freedom is the law it brings . . .

If Khodasevich uneasily straddles a variety of poetic strategies, there is a fascinating parallel to this in his views on self and society. The self is at one moment urged to “be a star that breaks away from the night” but in the next is “grunt[ing] to yourself, / looking for spectacles or keys”. This “usual self” is preoccupied with tarnished spires, the tops of cars, old iron eaves, and in ‘Berlin View’ sits shivering and sneezing in a café, surrounded by “plate-glass” reflections of itself. A couple of years later, at what seems a Dantesque ‘mid-point’ in his life, Khodasevich stares hopelessly into a mirror: “Me, me, me. What a preposterous word! / Can that man there really be me?” This is the Modernist side of the poet, observing from “the gutter”, watching a sordid Parisian cabaret, a dismal demi-monde of “tinselled chaos”. Yet the poem quoted here – ‘The Stars’ – goes on to suggest our gaze may sometimes incline upwards, “from the horizon to the stars” and – at least on occasions – we are aware of a “starry universe in glory / and the primordial loveliness”.

This suggests Khodasevich was still enough of a Symbolist to see the poet’s role as seeking out such “loveliness”, the transcendent within the quotidian (as Michael Wachtel’s Introduction defines this key Symbolist intent). This accounts for Khodasevich’s repeated images of stars often unseen above us (but still there) and also of the flourishing of seeds in the earth as an image of personal and social growth. The title poem of The Way of the Seed (1920), in rhymed couplets, describes the traditional sower, with seed gleaming golden in his hand, but scattered into “the blackness of the land”. There it finds “its moment for dying, and for growth”. Latterly, the poem suggests this is also the path of the “soul” as well as “my native country, and her people”. This nicely sums up Khodasevich – the progressive conservative, these organic and traditional images of the farmer absorbed into bold ideas of growth and change incorporating both a dying back and re-birth. A similar pattern is reflected in ‘Gold’ – a coin is placed into the mouth of a corpse, buried, and after many years, in the unearthed skull, the coin is found again, rattling: “the gold will flash in the midst of bones, / a tiny sun, the imprint of my soul”.

It is in such longevity, such insightfulness that continues to be true, that Khodasevich finds reasons to celebrate the poetic vocation. Though the names of the dead who fell at the Battle of Khotin (1739) are forgotten, “the Ode upon Khotin” by Lomonosov is still recited. ‘Ballad of the Heavy Lyre’ opens with Khodasevich in the Soviet-run House of the Arts, surveying his life and finding it “worthless, a quagmire”. But eventually verses burst from him till “a galaxy streams at my head” (those stars again) and a heavy lyre is mysteriously thrust into his hands and, in the final line, he understands this is the lyre of Orpheus. Written in 1921, this poem foreshadows Khodasevich’s departure from the Soviet restrictions in the following year with hopes (one imagines) of further freedoms to be enjoyed.

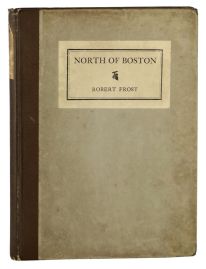

I was especially interested in the seven substantial blank verse poems Khodasevich wrote in a brief period between 1918-20 (David Cooke’s review of the book for London Grip makes the same observation). These in particular bring to mind the modernist-conservatism of Robert Frost (whose two first books were published in 1913 and 1914) and it’s astonishing that Khodasevich did not pursue these successful experiments with a less formal verse that seems an ideal vehicle for his quiet observational voice, his sense of the mystery or beauty that lies beneath the ordinary, his observations of a provisional self often encountering an unstable, uncertain world.

‘An Episode’ appears to record, moment by moment, an out-of-body experience Khodasevich had in 1915 (these blank verse poems are always keen to name times, places, people). At one moment, he sits before a shelf of books, at the next he is gazing at himself as if looking at “a simple, old, old friend”. The transitional moments are evoked through the marvellous image of feeling like a “diver, plunging to the deep, [hearing] / the running about on deck and the shouts / of the sailors”. ‘2nd November’ describes the aftermath of revolution – again the precision of street names, people’s responses as they emerge into the smashed and bullet-scarred streets makes this read as a very contemporary poem indeed. The narrator watches a neighbour, a joiner, building a coffin and painting it: “under the brush / the boards were turning crimson”. But the golden seed in black earth comes to mind again as a child is observed – a “four-year-old, chubby, in a flap-eared hat” – who manages a smile as if listening to Moscow’s “beating heart, / the moving fluids, growth” though for the narrator even Pushkin’s beloved works, on this occasion, fail to alleviate the shock of political change.

The unresolved tensions Khodasevich manages to hold together in these blank verse poems create a very modern impression. Another child appears in ‘Midday’, the narrator sitting in the most ordinary street scene, recalling a visit to Venice, fleeting glimpses of those “incandescent stars” once more. ‘An Encounter’ drops the star images for a more conventional image of beauty or inspiration, a “lovely English girl” glimpsed in Venice with its “black gondolas, / the fleeting shadows of pigeons, and the red / flow of the wine”. The extraordinary poem ‘The Monkey’ replaces the stars and the girl with the bizarre image of a tame monkey in a “red skirt”, led on a chain by an itinerant Serbian man (a much inferior translation of this poem by Alex Cigale can by read in The Kenyon Review). After a drink of water from a bowl, the monkey offers “her black and calloused hand” with such “nobility”. It’s the realism of the setting – the heat, the cock crow, the dusty lilacs – that enables Khodasevich to anthropomorphise the animal to such an extent and get away with it. It becomes another epiphanic moment in which the transcendent emerges from the quotidian. Here, a great chain of brotherhood seems implied and this makes the final line all the more devastating: “That was the day of the declaration of war”.

The two most Frost-like of these blank verse poems describe respectively a derelict house and a couple of neighbours chopping wood. ‘The House’ leads to reflections on transience, whether for a “palace” or a “shack”, the sudden advent of “war, plague, famine, or civil turmoil”. Such contrasts are again viewed from an Olympian height, an aloofness which has more negative capability about it than unfeeling Modernist cynicism. An old woman appears, scraping a living, and rather than pass judgement on her or her fate, the narrator joins her in stripping useful materials from the ruined house: “in pleasant harmony / we do some of the work of time”. A green moon rises ambiguously over the scene, casting light over a “tumbled” stove. Khodasevich’s rich embrace and acceptance are also evident in ‘The Music’ as two neighbours chop wood. One suddenly claims to hear music but try as he might the other cannot hear it. In ‘Mending Wall’, Frost’s narrator likewise teased his farmer/neighbour and drew from him an old saying: “Good fences make good neighbours”. Khodasevich’s poem yields only a sense of earthly work well done together, the remoteness of the sky (from which perhaps that music fell), the clouds passing onward as “feathery angels”, or perhaps they are really no more than clouds.