One of my most visited blogs in recent months was the provocatively titled How Do You Judge a Poem?, sparked by my judging the Torriano Poetry Competition 2015. The results are now in the public sphere and on the evening of Sunday 12th April, at the Torriano Meeting House in Camden, north London, many of the winners in the Competition gathered to share their poems.

All proceeds go towards funding the future work of the Torriano Meeting House and this year as there were no plans for winning and highly placed poems to appear in print, I thought I might grace this blog with them. The authors whose poems are included below have kindly given permission for them to appear and I have also included my own brief comments – all this in continuing pursuit of the vexed question of what it is that makes a good poem.

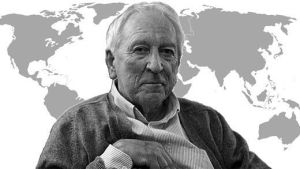

At the beginning of the awards evening I alluded to the sad news of the recent death of Swedish poet and Nobel prize-winner, Tomas Transtromer. In reading his work again in the last week or so, I was struck by this passage from his 1970 poem ‘The Open Window’ (in Robin Fulton’s translation). I thought it relevant to the evening as it starts in a familiar world, undergoes a mysterious transformation, all the while never losing sight of the need to keep our eyes open, our senses open. This for me is what poetry can do, must do perhaps, if we insist on setting poems into a competitive environment.

I stood shaving one morning

before the open window

one storey up.

I switched the shaver on.

It began to purr.

It buzzed louder and louder.

It grew to an uproar.

It grew to a helicopter

and a voice – the pilot’s – penetrated

through the din, shrieked:

‘Keep your eyes open!

You’re seeing all this for the last time.’

We rose.

Flew over the summer.

So many things [. . . ]

The urgency of (as if) seeing things for the last time is something we want from poems, the need to be spoken. We want the ability of a poem to open itself to the world around it, not to shutter it out with preconceptions, indeed with language itself. We want poems to contain ‘so many things’. Scanning the top 25 poems in this competition, their topics are love, relationships, war, the self, the body, ageing, politics (broadly defined), nature, language itself. So many things . . .

With apologies to the poets for some loss of some stanza break formatting (I still can’t make WordPress obey me on that), here are the texts of those poems for which I have permission, followed by my comments:

Winning Poem:

One Small Act of Survival – Claire Dyer (NB. this poem should appear in couplets)

In my hand a shiny new hammer

bought to forge a carapace from commonplace things:

door handles, empty soup cans, the almost-over

hyacinth blooms in my mother’s blue vase.

The shape I’ll fashion will not be symmetrical

but I’ll spend a while writing charms on its underside

then flip it, polish its surface until I can see my face in it.

It’ll be shallow and, roughly the size of silence.

Next up, a Stanley knife to incise my chest, peel back the skin.

My blood will blossom like chrysanthemums as I slide my creation in.

So much done in 10 lines! The poet as maker, as technician, rather than inspired Romantic genius – I have always loved poems that deal with the processes of things; how to, rather than look at me doing it. I like the modesty of the title, though that is promptly undermined by the importance of the word ‘survival’. The poem starts so well with its hammer and precise verb ‘forge’, though this is also immediately, clearly metaphorical, a gathering of raw materials, adding a little magic, till the object (as in all poems) is also a reflection of the self that made it. The brutality of the final lines has – by what has preceded them – come to be balanced between self-harm and self-repair. Blood as flowers is Sylvia Plath to some degree but this re-birth has more, is more, and is more convincingly, of the future tense than Plath’s ‘difficult borning[s]’ ever were.

*

Second Place Poem:

The Ghost Orchid* – Dilys Wood

I hear him claim, “A flower for all seasons –

only she needs no sun, no seasons . . . “, as if

this grey-haired plant hunter is thrusting

into the woven thickness of the forest

like a man into a woman. I ask

how rare this orchid is, has he seen it,

what kind of plant is it? “A plant

for the heart”, he says, “Of old woodland like this.

She’s very rare, in fact – has no green parts,

doesn’t photosynthesise, doesn’t exist

but the hundredth time you look in the same place

she’s there”. He’s fixated but quite normal,

stopping for a break in my patch of shade.

Common plants are there, low-growing Wood Sorrel,

Wind Flowers he calls ‘Wood Anemone’

with petals that blush like adolescence.

Her ashes (that’s my thin girl’s ashes)

are indistinct among small white flowers,

ferns, wood-ash from log-burnings on this spot;

but he sees how, with the box still in my hand,

I stare into the thicker trees for glimpses

of my strange one and how I’ve not spread out

but spilled her heap of absence on the ground.

We exchange photos for a minute. “It’s weird

enough?”, giving me his colour snap

of the ‘Ghost’ lit by a camera-flash,

and so albino, transparent, spectral,

I catch my breath. It’s so like my daughter,

or what we saw inside, her ‘lit-up’ self.

Running his fingers under Wood Sorrel leaves

to show delicate, bent flowers, he says,

“Life-cycles are so utterly diverse –

see a miracle in all lives, if you like”.

*The Ghost Orchid, Epipogium Aphyllum, is Britain’s rarest flower with findings reported in 1986 and 2010. It has been described, ‘In a torch beam . . . they appear translucent white . . . almost like a photographic negative’.

Dialogue is difficult to use convincingly in a poem but this poet dives straight in without context or scene setting, though as we are baffled we are also intrigued. The “grey-haired plant hunter” is a near relation of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner initially, though on this occasion he seems to need a little prompt or two to get going. Instead of a victim of experience though, he turns out to be a seeker – for the rare, the beautiful, the elusive, valuable precisely because so seldom of this world. The compassionate heart of the poem is only introduced (bravely) half way through with the more than strange coincidence of what the narrator is up to. The exchange they pursue is very moving, a quiet (can I say) English version of those often more hysterical scenes of mothers holding out photographs of the disappeared. The throw away ending is a stroke of genius, throwing this extraordinarily intimate moment back to the reader.

*

Third Place Poem:

The Haircut – Catherine Edmunds

She stands in front of the bathroom mirror, ties her hair back, presses

the fringe down flat on her forehead. It reaches over her eyes. She

picks up the scissors for the last time. First she thins the fringe, just a little.

There’s not much hair. Alopecia – stress related.

That’s what the nurse said. Here, have some pills.

Next she cuts along in a gentle curve, level

with the underside of her eyebrows.

He’s never known the colour of her eyes. They’d played that game once:

what would you sooner lose, a leg or an arm? Your hearing or your sight?

Okay, she’d said, go on – tell me the colour of my eyes. She’d shut them

tight, laughing, expecting the right answer, expecting a kiss.

The hairs drop into the sink. It will be blocked

by the time she’s finished.

She looks at her face in the mirror. There they are; her eyes,

her beautiful hazel eyes.

The fringe isn’t straight. She levels it, brushes it out.

Still isn’t straight. Snip-snip-snip.

Still. Not. Straight. snip-snip-snip-snip-snip-snip-snip-snip-snip

He’s suggested she dye it. Cover up the grey. Maybe bleach it,

go blonde, but get it done properly, he’ll pay. She’d sooner be a redhead.

She sticks the point of the scissors into her scalp, watches the blob of blood.

Stands and watches. Watches. The red blob settles, works its way

along a few hairs, glues them together. Darkens. She preferred the brighter red.

She slips the scissors under the skin. Snip. Snip-snip.

Raw and pink underneath. Snip. Snip.

And then she slashes at the hair, all the hair, and cuts and cuts until

it’s reduced to tufts across her head, and then she hacks at her scalp

to get rid of the tufts, hacks and hacks.

Pink. Oozy.

Her eyes are crying. She doesn’t want to see

her eyes crying. She holds the scissors firmly with both hands.

I agonised over this one because I doubted, at times, the intentionality of the effects. Yet even if the monstrously powerful impact was fortuitous – does that matter? The words do their work. I was agnostic because of the looseness, the long lines, the repetitions, the plainness, the directness. But aren’t these elements precisely what makes the poem so gut-wrenchingly unforgettable? Well – I stopped agonising and I went with the opening – so familiar as a moment of self-reflection, though not the condition briefly, dismissively alluded to. The relationship information is quick, convincing, just a facet of this person, not the whole story. How brave to be so repetitively onomatopoeic in the middle of the poem. Then it turns – sickeningly – on the word “redhead”, making it ambiguous, and so begins its horrible descent into drama. Perhaps into melodrama – but I teach teenagers and melodrama is a currency they trade in, knowing that it’s real.

*

5 Highly Commended Poems: Highly Commended of course means, that on another day, certainly perhaps with another judge, these poems might have been in the top three.

The Disappeared – Norbert Hirschhorn

What makes us human is soil.

Landfill of bones, shredded tees, jeans;

mass graves paved over for parking.

What makes us human are portraits

– graduation, weddings –

mounted in house shrines and on fliers, Have You Seen?

Names inscribed around memorial pools

or incised on granite. Names waiting,

waiting for that slide of DNA, any piece of flesh –

for the haunted to be put to rest.

What makes us human is soil.

To stare into a hole in the ground,

fill with the deceased, throw earth down,

place a stone. Bread. Salt.

For Fouad Mohammed Fouad

A triumph of tone this one – from the intriguing, imperturbable, magisterial judgement of the opening, end-stopped line through to the stalling, breathlessly punctuated, fragmenting, grief-stricken ending. Between those lines the poem plays with the tension between its hard, objective tone, concerned with evidence, details, the empirical gathering of science and its efforts to articulate what it is that makes us what we are.

*

When I Heard Your Chemo Hadn’t Worked – Carole Bromley

I had the urge to pick blackcurrants,

why it had to be blackcurrants and not blueberries,

raspberries or strawberries I don’t know. We never eat

blackcurrants, I guess because they must be cooked

with added sugar and if you boil the pan dry they stick

like crazy and even if the compote works it stains

and the stains never come out however many times

you put the clothes through the hot wash.

It rained on me so hard I had to park my bike

under a tree and try to shelter though the rain

meant business and hit my back over and over

like my mother that time I flicked water

down the stairs at my brother and didn’t know

she’d spent all day painting the landing and hall.

When I got there the notice said Far Field

and I walked miles and there were only blackberries

and I’d set my heart on blackcurrants.

Then I spotted the bushes and there was no-one

else and even though it started to rain again and my shoes

were getting stained purple, I didn’t care, just crouched

down and milked the fat black drops into the bowl.

A poem that triumphantly recovers from its own title – because the poem itself avoids any reference to the situation about which the title has to inform the reader. What we are left with is a direct, if self-mystifying, narrative. This is a search, a little quest, haunted by the indelible, the irrevocable, by stains. It’s a trial narrative, a coming through, a survival, but the grail here is extraordinarily equivocal; listen to the verb applied in the final line to the gathering of this ominous crop.

*

My Humble Body – Kate Foley

Just as a cloud becomes more

or less as it frays,

my humble body

is slowly learning to speak.

Not hint, not whinge

but say direct to my face

‘I am your face.’

‘Oh?’ I answer from somewhere

up here.

‘Yes! Not the memory

of your face, its trace

in old mirrors

but the now of it.’

And my body, no longer so humble,

like an old donkey with a spring

in its heels says ‘Listen!

Rough bits, wrinkles, furrows

where half-buried truths lie,

twinges, and you up there, we

can’t wait forever. It’s

now or never

to get together!’

‘Cliche!’ I smile,

scoring a point

but my body raises

its suddenly wise

hand and places

a gentle finger on my lips.

I’ve always disliked those poems which record a dialogue between the soul and the body, but this one convinced me (though I don’t know if ‘soul’ is the right word). The directness with which the humble body begins to speak is reflected throughout the poem in its clean, economical, lean lines. The progressive ironising – indeed, mickey-taking – of the soul/self’s arrogance is an object lesson in gradualist narrative development

*

At the War Museum – Tony Lucas

Here is the shadow that was always at

our backs, though we were shielded. We knew

the stories – or the ones they chose to tell

to us, to tell themselves. Also the silences,

events that no one dared to mention.

These faces look familiar – recall the ones

who brought us up, who filled our world, but here

in uniform, removed to strange locations,

and performing tasks we never saw

them do. This is the world made strange, furnished

with obsolete contraptions that delivered

death, the well-known places mostly wrecked –

a quiet church you visited last year,

calm as Wren left it, is shown broken, open

to the sky, with shattered monuments;

a library’s hush, all raucous debris, plaster dust –

and if that happened to the books, what of

the people shelved in tidy residential

streets, gap-toothed with rubble, bathrooms

bared, paper hung ripped from private walls?

They had their modes of coping with it all –

swagger and slang, ‘business as usual’, wink

of an eye – that got them through. Styles

at first quaint to us, and now a foreign language.

Pictures, writings that seemed so peripheral

at the embattled time, now offer

our most intimate approach to this

alternate world. While, always, looming

back behind, what they themselves half knew,

an elder dark – of shells and mud, of gas

and blasted stumps, torn flesh and broken minds,

that forged, and warped, the world in which we grew.

This struck me as the most ‘well made’ poem in the top rankings. Though not using end rhyme, the quatrains are carefully controlled, making good use of the de-stabilising of enjambement. There is a formality in tone too, from the title onwards. A distance perhaps but that enables the narrative voice to reflect, to judge and in the end to compassionate with the elder generation who suffered the horrors of war.

*

Theft – Josh Ekroy

Awaiting permission for this text

The opening lines of this poem have an epigrammatic quality to them which the subsequent lines proceed to follow to their logical conclusion (though perhaps with a bit of black magic thrown in). This is like Blake in the mood of ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’ and this poem gives us more modern Proverbs of Hell, reversing our preconceptions to both comic and politically serious effects.

*

10 Commended Poems:

Body Evidence – Alexandra Davis

Kentucky Fried Chicken in Georgia – Valerie Darville

The Man Whose Car was Stolen… – Christopher North

Ordinary Love – Noel Williams

Vulcano – Julie Mellor

Dear Revisionist – Martin Malone

A Sedge of Herons – Noel Williams

Teign – Roland Malony

As the days play on – Maria Stasiak

Quickly – Sue MacIntyre