In the early 1980s I arrived in Oxford as a self-absorbed post-graduate and promptly sought out student poets wherever I could find them. The group I joined was then (I think) meeting in rooms in Hertford College, opposite the Bodleian Library (and happily very close to the Kings Arms). Bill (W N) Herbert was there, as was Keith Jebb and Paul Mountain. The group, with changing personnel – I remember Elise Paschen was a member for a while – continued to meet throughout my 4 year stint among the dribbling spires, but we would supplement it by decamping to the Old Fire Station on George Street where Tom Rawling was running a public workshop. Tom had taken over when Anne Stevenson moved north. As a retired headmaster, Tom ran us all as a well organised and disciplined class. Elizabeth Garret joined later and I think Peter Forbes was already a member, as was Helen Kidd. Jeremy Round, who was soon to achieve short-lived fame for his cookery writing, was also a regular. My poem ‘In Memory of Jeremy Round’ (eventually published in Beneath Tremendous Rain (Enitharmon, 1990) https://martyncrucefix.com/publications/beneath-tremendous-rain-1990/) is a lament for his tragic early death, but also tries to paint a vivid picture of the workshop and its members:

We’d wrangle inconclusively

between the beers and crossfire from Tom,

elder statesman who’d slip quietly glittering

poems from his tackle bag like fish; from Helen,

whose pages always seemed typed under earthquake

conditions, whose baggy poems had more passion

than most of us could muster; from Peter’s

exactitude, schooled on a diet of science, he held

each piece like a prism till it shed eloquent

rainbows; from Bill and Keith, the ferocious

tyros, the university wits, who minced nothing

but their language into strange sweet things;

from Paul whose poems were amazed not to find

themselves loosed into a more graceful age

than the one we live in.

There were others writers, of course, to whom I apologise for not recalling them clearly. Bill has also written about these few years with great eloquence and insight: http://tracearchive.ntu.ac.uk/poets/herbert/dec_2.htm.

But rather than his aspiring students, it’s Tom Rawling’s own poetry that I want to highlight. A pamphlet called A Sort of Killing appeared in 1978 (an historical event now as this was one of the first publications by a young Neil Astley). OUP published Ghosts at My Back (1982). Two other books followed: The Old Showfield (Taxus, 1984) and The Names of the Sea-Trout (Littlewood Arc, 1993).

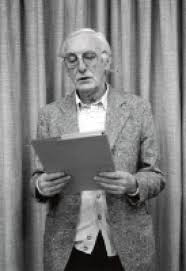

Grevel Lindop has long been a fan of Tom’s work (http://grevel.co.uk/poetry/tom-rawling-rediscovering-ennerdales-poet/). There is an audio recording of Tom reading many of his best poems (you can listen to one of them here: http://listenupnorth.typepad.com/listenupnorth/tom-rawling-poet.html). Listening to him again, what what comes over is his modesty, his sharp intelligence, his confidence in his own work and the vivid recall he had of his formative years, growing up in Ennerdale, Cumbria. Tom’s poems, in their accessibility, boldness with language, natural and ecological themes are (as my review concludes) ideal for the classroom and it is still a cherished hope of mine that they might be taken up by a mainstream publisher and presented to a new generation (a Rosemary Tonks of the western valleys of Cumbria, wielding his fly-fishing rod). Perhaps the best way to sing my praise of Tom’s work is to post up a review I wrote of his posthumous collection How Hall (2009).

I recommend you search out more of his work (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Rawling). Here is my review:

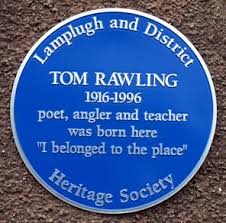

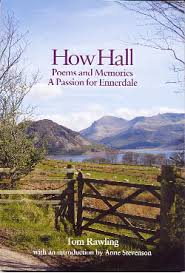

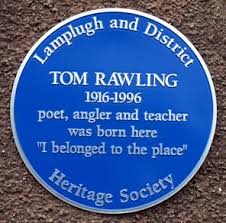

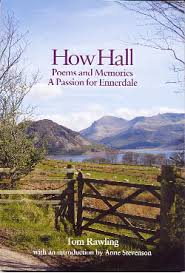

Tom Rawling, How Hall: Poems and Memories, a passion for Ennerdale (Lamplugh and District Heritage Society, 2009), £7.50, ISBN 978-0-9547482-1-0

Tom Rawling, How Hall: selected poems of Ennerdale poet Tom Rawling, read by the author (Lamplugh and District Heritage Society, 2009), £5, CD audio recording

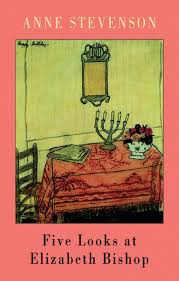

As a child in the 1920s, Tom Rawling grew up in the Ennerdale valley in what was then called Cumberland. It was not until his retirement in the shallow decades of the 1970s and ‘80s that he began to write poetry as a man “haunted . . . even bullied by his memories” as Anne Stevenson’s insightful introduction to this new selection explains. A marvellous collection was published by OUP in 1982 and two further publications from smaller presses resulted, but at his death in 1996 Rawling had not attracted the kind of attention he had hoped for and certainly deserved.

How Hall is a new edition of more than 70 poems, three pieces of autobiographical prose and some wonderfully evocative photographs. The accompanying CD is an audio recording of an extended reading given in 1983 and the passion and precision of his voice and his humble and insightful comments add further invaluable dimensions to any appreciation of his work. Rawling shares with Heaney the kind of vivid recall of childhood that yielded the title of his first book, Ghosts at My Back. An early poem has the young Rawling playing “squire” to the village blacksmith who also introduced him to his life-long passion, fishing – both are described as “tying knots / That didn’t slip” (‘Johnny’). Yet home life was not always so easy and there are poems that bitterly lament the repressed and repressive life of his mother (‘Hands’), his father’s drinking (‘Honour thy Father and thy Mother’) and the son’s rebellious, divisive “radical words” (‘Clipping Day’).

His rebellion took him away from home, but ironically it is for the authenticity of Rawling’s responses to the farm life and countryside of the Ennerdale of his youth that we should continue to read him. Perhaps it has taken us 25 years to understand what he felt intuitively, the importance of our relationships with the natural world and the kind of folklore that once bound man and nature together. Even in the 1920s, it was only Rawling’s grandmother who “glimpsed beyond the byre” to the atavistic fertility beliefs that lay behind “ritual no longer understood” (‘Grandmother’); it was she who knew the spell to complete a whistle carved from hedgerow sycamore (‘Sap-Whistle’). ‘The Barn’ vividly evokes the thrill of the hay harvest: “Bright prongs pierced and unpicked, ash handles / bent, they launched the bundles we embraced” and as the barn filled it was only when “heads bumped the slates / we came down the ladder in triumph”.

Anne Stevenson – who met Rawling in Oxford in the late 1970s – rightly directs us not to dismiss his work as “romantic retrospection” because he really “wrote poems to tell the truth and in them rehearsed the daily rituals of life and death”. ‘Rumbutter’ characteristically revels in that recipe’s “sweet beginning” as well as, “not quite hidden, the cinnamon / of the coming funeral feast”. There is certainly no room for sentimentality in Rawling’s view of nature: a pig is to be cared for only till the “pole-axe fell” (‘Hooks in the Ceiling’) and chickens are nurtured carefully, but in their “due season, each neck pulled / . . . the admired knack of killing” (‘Feathers’). Rawling also shares with Heaney a fascination with the insights embedded in idiom and dialect. ‘Hearthwords’ addresses the younger Irish poet with their shared belief that “the naming spell / gives the thing itself / into our hands” And then, as his own poetry began to flow, he swiftly developed a precise, lean, direct form of free verse, capable of moving from the joyous observations of “cloud and sun pursu[ing] / Their steeplechase across the land (‘I Am What I Was’) to the shockingly frank recording of the realities of the cow shed: “ a column of piss / cascades to the cobbles . . . a face gurning, whistling and whispering soft farts” (‘Privy’).

But Rawling’s reach is not confined to the material. Perhaps his most distinctive poems are those that deal with angling, especially fly-fishing for salmon and sea-trout which his poems transform into an almost religious questing and testing of the individual’s devotion, skill and subterfuge. His own first encounter with the power of the sea-trout he recalled as a moment when he had “waded / into mystery, tampered with Leviathan” (‘Leviathan’). One function of any poem is to offer us profound if vicarious experiences and these poems succeed so well in this evocation, taking us to the riverside at night, “to the dub / where sea-trout rest” where we might “hear an old ewe’s husky cough, / the water slopping, slapping” (‘Night Fisherman’).

Poem after poem makes it clear that to fish in this way is to engage differently, intimately with the world and to embark on the difficult process of laying aside our humanity’s hobbling self-consciousness, to cast off the accretions of civilisation until we allow “the body [to] flow into the rod” (‘Torridge Salmon’), achieving a different form of consciousness as we “wade in deeper, / Share with the fish / Its lateral line / The current’s push” (‘Only the Body’). It’s easy to understand why Ted Hughes came to admire these poems as Rawling triumphantly celebrates the efforts and occasions when we encounter the Other in what becomes a frankly spiritual communion. So in ‘A Shared Rod’, a kingfisher perches on the “bamboo rod-tip” as the angler waits in the reed bed:

His great eye turns, a moment’s stare,

then, blue-green whirr,

the arrow skims downstream,

leaving an emptied space,

a shared rod quivering.

It is really this kind of encounter – with all that is not bounded by ourselves – that Rawling is conjuring in ‘The Names of the Sea-Trout’, a spell for fishermen that revises and revivifies his grandmother’s superstitious connections with the natural world:

Bender of steel, the breaker, the smasher,

The strong wench, the cartwheeler,

The curve of the world,

She who doesn’t want to surrender,

The desired, the sweet one.

Profound, vivid, honest, accessible – these are poems that at once connect us to a lost past and prepare us for a world in which the environment must again become our close companion. Rawling’s work would be wonderful to teach in schools if it were more easily available and a mainstream publisher would do well to bring him nearer centre stage. For the time being we must thank Michael Baron, Stan Buck and the Lamplugh and District Heritage Society for the very many pleasures of this marvellous book.