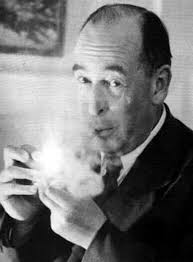

By 1956, C.S. Lewis was famous as a Christian apologist, literary historian, critic, BBC broadcaster and a writer of science fiction and children’s books (the Narnia books appeared almost yearly from 1950 to 1956). He had long been a confirmed bachelor, living with a housekeeper and his brother in Headington, just outside Oxford, since 1930. For most of his life he’d been a don at Magdalen College, Oxford. Just the year before, in 1955, he had accepted a new professorship at Magdalene College, Cambridge, but remained living in Headington. An establishment, if eccentric, figure whose views on so many things are scarred by the era in which he grew up, nevertheless he is a writer capable of remarkable insight.

He first met Joy Gresham in September 1952 and the two grew closer over the ensuing four years. Gresham was an American whose marriage was collapsing. By 1956, she wanted to remain in the UK with her two children, but the Home Office refused to renew her visa. To secure her residence, Lewis offered to marry her in a civil ceremony in a registry office. He seems to have suggested that he already loved her in all ways but one – the erotic – and he would continue to do so. In fact, they had just four years of marital happiness (and a love that seems to have included the erotic) before Gresham died of cancer in July 1960. Lewis jotted thoughts down after the event, referring to it as a record, “a defence against total collapse, a safety valve”. What he wrote was published in 1961 (under a pseudonym) as A Grief Observed. A version of these events is played out in the film Shadowlands (1993).

A Grief Observed does what it says on the tin. Lewis observes the progress of his own grief after the death of Joy Gresham – she’s referred to in the text as Helen. For example, “No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering in the stomach, the same restlessness, the yawning. I keep on swallowing.” A little later: “I am thinking about her nearly always. Thinking of the H. facts – real words, looks, laughs, and actions of hers. But it is my own mind that selects and groups them. Already, less than a month after her death, I can feel the slow, insidious beginning of a process that will make the H. I think of into a more and more imaginary woman.” It’s these thoughts about a closely observed mental process that particularly interested me.

Way back in 1926, in a now mostly unread long poem of ‘scientifiction’ (as he called the sci fi genre) called Dymer, an individual who for years has been refined, clipped, moulded and adorned by an oppressive regime suddenly acts freely: “Then came the moment that undid the whole – / The ripple of rude life without warning”. On that occasion, the rebellion of real/rude life takes the form of an almost inadvertent violent action. But this pattern of the mental/social construct being breached by an undeniable and more authentic reality seems for Lewis to have been one of those magnetic norths that serve to guide any reflective individual’s thinking. In Lewis’ religious thinking, the authentic was, of course, the presence of God. Epistemologically, he never doubted a real presence behind all perceived phenomena. And this is the point he makes in relation to his recall of his wife.

The accumulating false image of Helen would, of course, be founded on fact, nothing fictitious as such, but the composition of the image would become more and more his own. He compares the process to the settling of snowflakes: “little flakes of me, my impressions, my selections, are settling down on the image of her. The real shape will be quite hidden in the end”. Eventually, if the process continues uninterrupted, the image “will do whatever you want. It will smile or frown, be tender, gay, ribald, or argumentative just as your mood demands. It is a puppet of which you hold the strings”.

Lewis wonders if this is the real meaning of all those ballads and folk tales in which the dead return to the living to inform us that our mourning somehow does them wrong. Counter-intuitively, he argues it is our passionate grief that actually cuts us off from the dead. In such moments, because of the power of our emotion, all is “foreshortened and patheticized and solemnized by [our] miseries”. The real presence of the lost one is swamped and submerged beneath a passionate egotism. Lewis observed something resembling this just a week after Joy’s death. An American, Nathan Starr, who he’d not met up with for years, visited him in Oxford and, in his notes, Lewis wrote: “don’t we often make this mistake as regards people who are still alive – who are with us in the same room? Talking and acting not to the man himself but to the picture – almost the précis – we’ve made of him in our own minds? And he has to depart from it pretty widely before we even notice”.

This matters less when the real person is on hand to breach and explode the fictional composition we make of them – though Lewis is right to note how tenaciously we hang on to our précis before accepting its divergence from the real. But in the case of the dead? “The reality is no longer there to check me, to pull me up short, as the real H. so often did, so unexpectedly, by being so thoroughly herself and not me”. In some of his most moving lines, this ageing don and once-confirmed bachelor argues: “The most precious gift that marriage gave me was this constant impact of something very close and intimate yet all the time unmistakably other, resistant – in a word, real”. One of Lewis’ great gifts was his ability to communicate. He often declared his belief in the vernacular, even (or rather especially) when it came to religion, arguing the vernacular was the real test – if beliefs could not be turned into it, then either you didn’t fully understand them or you didn’t truly believe them. In A Grief Observed, he describes what he misses of his wife’s real presence, “the rough, sharp, cleansing tang of her otherness”. In contrast to the puppet-like, “insipid dependence” of the image or précis created by the person left behind, the lost one’s real presence was “obstinate, resistant, often intractable”.

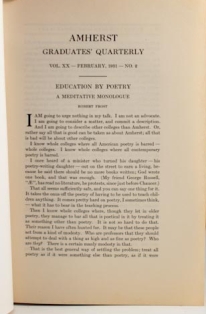

Moving from this particular to the general, it’s here that Lewis memorably declares “all reality is iconoclastic”. Our true acquaintance with reality or real presence is the only way to cleanse and scour our egotistical preconceptions whether of the dead or the living: “Not my idea of God, but God. Not my idea of H., but H. Yes, and also not my idea of my neighbour, but my neighbour”. In William Griffin’s hyper-episodic biography of Lewis, he reports a 1944 BBC broadcast given by Lewis in which he refers to Christians as “new men”, a new step in evolution. This is because they have abandoned their own personalities and allowed God to inhabit them. In looking for your self, Lewis argued, you find only hatred, loneliness, despair and rage. In turning away from the self we find “Him, and with Him everything else thrown in”. This is interesting as it’s a later (though ironically more traditional) version of Keats’ Godless explanation of the importance of negative capability (which I have discussed at length elsewhere).

Whether in Keats’ or Lewis’ view, what the individual – whether we think of ourselves as artists or not – must always bring to the table is our attentiveness. The etymology of the word attend shows its roots lie in the Latin verb tendo – to stretch, to stretch out. The effort implied is the energy and precision with which we must perceive and this energy breaches the accumulated shell, the snow-cover of our preconceptions. At the close of A Grief Observed Lewis says “Attention is an act of will. Intelligence in action is will par excellence”. The willing poet, of course, must apply attentiveness in 3 directions – to the outer world (including the living and the dead), to my inner conditions, to my language.