Don Paterson’s 1997 book, God’s Gift to Women (Faber) includes a poem sporting the title ‘On Going to Meet a Zen Master in the Kyushu Mountains and Not Finding Him’. The reader’s eye hops off the perch of this lengthy title only to flutter down, looking in vain for a foothold, for a line, even a word – it’s a completely blank page. In a collection that includes a poem called ‘Postmodern’ and another on ‘The Alexandrian Library’, the joke is obvious enough. Any search for ‘masterly’ advice in the Kyushu Mountains or closer to home in a post-modern, relativist world in which language hides as much as it might reveal, must draw a blank. I remember seeing the poem – probably heard Paterson ‘read’ it too – the long title building expectation, a too-long pause, the announcement of the next poem (cue laughter) – and something bothered me. I think now I know what it was.

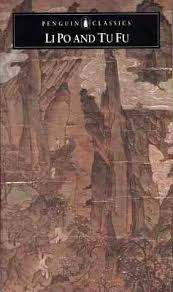

I wondered if Paterson had been reading the Penguin Classics selection of Li Po and Tu Fu (tr. Arthur Cooper, 1973). The Li Po selection opens with the poem ‘On Visiting a Taoist Master in the Tai-T’ien Mountains and Not Finding Him’. Cooper’s note tells us that ‘Visiting a Hermit and Not Finding Him’ is actually a very common theme in Chinese poetry. Such a poem (we are told) is not just an excuse for a “nature poem” but relates to the frequent “spirit-journeys” that Li Po was fond of writing. Here is Cooper’s translation:

Where the dogs bark

by roaring waters,

whose spray darkens

the petals’ colours,

deep in the woods

deer at times are seen;

the valley noon:

one can hear no bell,

but wild bamboos

cut across bright clouds,

flying cascades

hang from jasper peaks;

no one here knows

which way you have gone:

two, now three pines

I have leant against!

I had come across this poem while compiling my first book, Beneath Tremendous Rain (Enitharmon, 1990). I liked it for reasons I didn’t then understand and, in a very simple form of translation, I wrote an up-dated version:

Looking for an Old Man

Where red dogs bark

on the sodium ring-road

and traffic noise

blackens adjacent houses,

I’ve come to seek you.

In each garden I pass,

pale heads of bindweed.

The night is undistinguished.

The savour of coalsmoke

flattens across the kerb.

No-one here knows

which way you have gone:

two, now three lampposts

I’ve leant against.

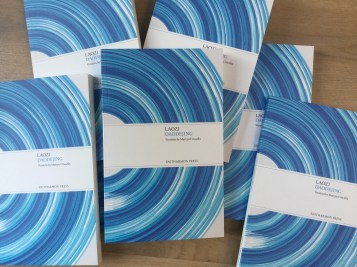

Li Po is the more Daoist of the two poets presented as a complementary pair in this Penguin book. Now, with a bit more understanding of this tradition, I’m sure that 26 years ago I was responding to something at the heart of the poem. The fact that the Daoist master cannot be found by the searching student is precisely the point since the Daoist teacher teaches “in the absence of words” (Chapter 43, ‘Best Teaching’) as I translated it in my version of the Daodejing (Enitharmon, 2016).

Interestingly, Li Po’s poem expresses this not with a blank page but (as Cooper says) through further encounters with “nature” (petals, woods, deer, valley, bamboo, clouds) or, in my version, the natural and urban world (ring-road, traffic, houses, garden, bindweed, coalsmoke, kerb). Whether we designate this a ‘spiritual’ journey or not, the point remains that the student’s search for knowledge in the form of a direct download from some master must be denied. The student’s anxious search for guidance is reflected in the number of pines/lampposts he leans against as well as the geographical over-specificity of the titles of such poems. The student’s dependency and naïve optimism is the satirical butt of the poem as he is directed back to the source of all knowledge (the world surrounding him) even as he wanders in search of his master. So Paterson’s 1997 version achieves three things: it misrepresents the spirit of the original, it’s more dramatic (comic), it’s more superficial.

When I first read Li Po’s poem I was coming off the back of doctoral work on the Romantics, especially Shelley whose ‘A Defence of Poetry’ (1821) argues that the “poetry in [our] systems of thought is concealed by the accumulation of facts and calculating processes [. . .] we want the creative faculty to imagine that which we know”. This is succinctly put in Keats’ idea of Negative Capability, defined as a passive openness to the fullest range of human experience (“uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts”) without any imposition of preconceived notions, ideas or language: “without any irritable reaching after fact & reason”. The student in Li Po’s poem seeks just such certainties and facts and is gently deflected back into the world of observation where (I take it) he is encouraged to pursue a more full-blooded, full-bodied, open-minded encounter with the 10,000 things which (in Daoism) constitute the One, ‘what is’.

The two attitudes to knowledge here are really two ‘ways of being’ as Iain McGilchrist’s fascinating book, The Master and his Emissary (Yale, 2009) phrases it. McGilchrist argues that right and left human brain hemispheres deliver quite different kinds of attention to the world. The left perceives the world as “static, separable, bounded, but essentially fragmented [. . .] grouped into classes”. Shelley described this in 1821 and linked it to the processes of Reason and this is the attitude to knowledge and education that the anxious student of Li Po’s poem possesses. In contrast, what Shelley calls Poetry or the Imagination is what McGilchrist associates with the right brain. It tends to perceive “the live, complex, embodied, world of individual, always unique beings, forever in flux, a net of interdependencies, forming and reforming wholes, a world with which we are deeply connected”.

Without doubt, this is also the viewpoint of the Daoist master whose teaching evokes the uncarved block, the One, and who teaches best without words. Ordinary language usage is dependent on conceptual thought which is left-brain work – ordering, categorising, re-presenting the minute particulars of the world as they are perceived by the right brain. I imagine that Li Po’s master-teacher and sage is deliberately hiding somewhere beyond the bamboo canes – and this is part of the student’s lesson.

So Don Paterson’s blank page bothers me because – as McGilchrist expresses it – it represents a rather glib, post-modern position, a scepticism about language which is in danger of throwing out the interconnected real world along with the suspect tokens and counters of left-brain language: “To say that language holds truth concealed is not to say that language simply serves to conceal truth [. . .] or much worse, that there is no such thing as truth” (McGilchrist, p. 6). I’m also reminded of Yves Bonnefoy, engaging in his own battle with the early stirrings of French post-modernism. He writes: “This world here exists, of that I am certain [. . .] It is simply with us. In what can be felt and sensed”. In The Tombs of Ravenna (1953), he names this underlying truth, not as existence, but as “presence”. The right brain knows this; the left brain sets about fragmenting it, making use of it, disappearing it.