This week’s announcement of the award of the King’s Gold Medal for Poetry to George Szirtes gives me the opportunity to re-post a long and detailed review I wrote (for Poetry London) of the two books that Bloodaxe Books published to celebrate Szirtes’ 60th birthday. These were the New and Collected Poems and a critical book about his work, Reading George Szirtes, written by John Sears. Though Szirtes has continued to publish a good deal since the late 2000s, this review still seems to me to have something useful to say about the development and poetical achievement of this outstanding writer and might be of interest to those not yet familiar with his work. (For WordPress readers, I am experimenting with posting also on Substack. Do subscribe here if you’d like to read in that format: https://open.substack.com/pub/mcrucefix/)

This 500-page New and Collected Poems demonstrates the breadth and depth of George Szirtes’ achievements and will bring his work to even wider notice, casting the poet as a recording angel. His lines of literary influence run from Eliot’s phrase-making and metaphysics, through Auden’s formalism and politics, to earlier contemporaries like Peter Porter and Martin Bell (at the Leeds College of Art and Design). There are distinct phases to Szirtes’ oeuvre, but his work tends to a density of fragmented detail, bound by a allegiance to visible form, shot through with explicit theorising about perception, language, time, memory, self, the art itself. This is a heady and immensely ambitious mix – not one likely to appeal to popular tastes, but there is no-one more dedicated to poetry, to playing the long game, to bringing a uniquely European perspective to the theme of our age, the search for personal identity.

Szirtes’ career illustrates what Pasternak discusses in An Essay in Autobiography (Harvill, 1990). Though our experience of the world is necessarily subjective, there is a sufficient underlying matrix that remains “the common property of man” – the hard-wiring implicit in being human. Superimposed on this is the softer wiring derived from upbringing, environment and education, and the self is ultimately a function of these base matrices in progressive interaction with individual decision-making in the flow of experience. So the objective world is processed through the individual’s particular matrices – his/her sets of harmonies and disharmonies – and must emerge coloured, spun, texturised as it were, accordingly. From this, Pasternak argues that when an individual dies he leaves behind his own unique “share of this . . . the share contained in him in his lifetime . . . in this ultimate, subjective and yet universal area of the soul”. This, of course, is where “art finds its . . . field of action and its main content . . . the joy of living experienced by [the artist] is immortal and can be felt by others through his work . . . in a form approximating to that of his original, intimately personal experience”. Art can be defined as the expression of experience playing across the matrices of the self, saying not this is me, but this is, this was, mine.

It is the raw imagery of stasis and movement that emerges in Szirtes’ early work as being truly his and it blooms into the maturity of the late 1980s. In short lyrical pieces the point of stasis is associated with the preservative of art in the spit ball gobbed by a foreign worker in ‘Anthropomorphosis’ which is caught and “suspended” by the poem. The afternoon rearranges itself around it and even the narrator “hung there / Encapsulated in that quick pearled light”. Versions of this encapsulation abound: girls creating a silver foil tree find themselves absorbed into a Keatsian “cold pastoral”. Such freeze-frame moments anticipate Szirtes’ sustained meditations on photography but early on, images of snow and frost suggest the ambivalent status of such suspension. In ‘The Car’ a snowfall is both beautiful and sepulchral: “Fantastic Gaudi-like structures hung / Under the mudguard . . . . / Wonderful, cried the girls under the snow”. A girl who is observed sewing causes consternation (“I do not like you to be quite so still”) caught in a stasis that can “eat away a life” that can “freeze the creases of a finished garment” (‘A Girl Sewing‘).

In contrast, it is movement in the shape of the passage of time that spurs many other early poems and the artist’s power is limited to “measure breath in a small space” (‘Group Portrait with Pets’). The enigmatic title poem of the first collection seems to teeter elegantly along the knife-edge of the sense of threat to domesticity and the desire to secure in a “cage” and convert to “metaphors” (‘The Slant Door’). It seems for time there is “no use, no cure” (‘Silver Age’) and Szirtes senses this especially in the domestic sphere. ‘House in Sunlight’ casts the busy sun as the agent of transience threatening the house itself and the life within it:

Whoever lives here knows what they are about –

Forms appear suddenly in mirrors and photographs,

We do not think however that they are entirely at home.

x

At night the doors are locked. We lock them now.

John Sears’ book is a comprehensive academic review of Szirtes’ career, tracing the development of both key themes and formal experimentation. He suggests Martin Booth’s 1985 critique of Szirtes’ early work as “withdrawn and laidback” was influential on the poet. Booth suggested that Szirtes might try writing about “his childhood” (Sears, p. 61). If true, we have reason to be thankful to Booth, but there are signs that Szirtes was moving in this direction already. He travelled to Hungary in 1984 and was casting his gaze beyond these shores towards people who “lie in complete unity / In graves as large as Europe and as lonely” (‘Assassins’). The title poem of Short Wave (1984) deploys its central image to suggest the deciphering of voices that are obscure yet seem suggestive of “all Europe in her song”. The self-deprecating picture of Szirtes “listening / and turning dials, eavesdropping” is something to be treasured given the explosive impact these deciphered voices will eventually have on his work.

Several members of Szirtes’ family were caught up in the Holocaust and later in the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956, escaping to the UK. Much of this was known to Szirtes only sketchily and he set himself the task of recovering what seemed lost. It is because Szirtes’ underlying matrices as an individual – stasis and movement, preservation and loss – mapped so powerfully onto his family’s own history and this history encompassed important European historical events that his work becomes in the late Eighties so much more complex, ambitious and important. History had determined his nature as a poet; his nature as a poet primed him to be able to encompass the burden of his own history.

So the title poem of The Photographer in Winter (1986) attempts the imaginative recovery of Szirtes’ mother from the Budapest of the 1940s and 50s. She was herself a photographer and her son traces her movements with “thoroughness and objectivity” as far as he can. Both as an artist and poet, Szirtes declares he has been “trained / To notice things” (the deliberate echo of Hardy’s ‘Afterwards’ is but one example of Szirtes’ very frequent intertextual allusions). But the recovery process seems often subject to disintegration, “trying to focus through this swirl / And cascade of snow”. At times the tone is more optimistic, like the final section of ‘The Swimmers’ in which a drowning girl survives the “icy Danube”. Elsewhere, intervening time destroys so much, and the later sequence ‘Metro’ (1988) uses the image of the Budapest underground system for “everything that is past, the hidden half”. His choice here of the deliberately curtailed thirteen-line sonnet is a characteristic recognition in formal terms that the search must remain incomplete.

The balance between one man’s search for his background and the conversion of this to poetry is a difficult one and if the marvelous sequence ‘The Courtyards’ is counted as one of the great successes, for me ‘Metro’ itself tips too far away from the memorial towards the monumental. There are occasions when Szirtes’ desire to recover and pay respects to his own history impels him to erect such elaborately formal accumulations of images that the reader may feel excluded, even if always impressed. The later ‘Transylvana’ is another occasion when the act of imaginative recovery can seem propelled for its own sake and despite the glittering formal achievement – terza rima in this case – the piling of detail on detail can become wearisome.

But Szirtes’ openness to theoretical thinking has always propelled his work forward and often derives more from his training in the visual rather than the literary arts. Blind Field (1994) draws on Barthes’ idea that in photography all that is not portrayed in an image may be implied by the presence of a “punctum” or detail within it. As Sears suggests (this is the sort of idea he is very good at elucidating) this bears some relation to Eliot’s objective correlative but is seen by Szirtes as a solution to the paradox that art stills the life it presents: “Out of this single moment a window opens” (‘Window’). This sense of the ballooning fluidity of experience, past and present, is one thing that marks his work as Modern and Post-Modern and it’s no surprise to see Szirtes countering Larkin’s belief that the passage of years makes us “smaller and clearer” arguing we grow “blurrier, vaster, ever more unfocused” (‘On a Young Lady’s Photograph Album’). It’s this slipperiness of personal identity that is Szirtes’ true theme and the one that elevates his work above the merely personal into a body of work addressing urgent contemporary concerns. As the poem ‘Soil’ puts it “there is nowhere to go / but home, which is nowhere to be found . . . / the very ground / on which you stand but cannot visit / or know”.

Everywhere these days, the recovery/re-construction of our own identities seems to be a pressing issue and the three sonnet sequences in Portrait of My Father in an English Landscape (1998) triumphantly present and simultaneously enact this process. Sears describes Szirtes’ form here as a “deliberately baroque form of the Hungarian sonnet sequence” or sonnets redouble (Sears, p. 145) in which the final line of each sonnet is repeated (approximately) as the opening line of the next and the final (fifteenth) sonnet is composed of approximations of each preceding sonnet’s closing line. Yet this is not an arid exercise in form as the recurrences and accumulations enact precisely what Szirtes believes is the process of the construction of the self – largely via language into a “lexical demesne” – in this case said to be “part Hungary, part England” (‘The Looking-Glass Dictionary’).

Retaining his love of the titled sequences, sections and subsections which had helped him draw a bead on his family’s obscured past – a tendency which produces the most typographically diverse and complex contents pages I’ve ever seen – from the late 1990s Szirtes’ work turns a firmly European gaze on the UK. An English Apocalypse ranges through Great Yarmouth, Keighley, Orgreave, Preston North End. all-in-wrestling and antisemitic violence towards images of “a tense / empire that could fall” (‘All In’), towards something “crumbling – a people possibly” (‘Dog-Latin’) and specific individuals “speaking the innate vernacular // of the trapped. He’s shit. Scum” (‘Offence’). Despite the success of Reel (2004), the new poems in this 2001 compilation, portraying an outmoded and disconnected England, are one of the high points of Szirtes’ career so far and they culminate in the extraordinary sequence of imagined apocalypses by meteor, power cut, deluge and suicide that caught the flip side of millennial euphoria and seem now years ahead of their time.

Apart from the sceptical cinematic pun Reel/real, the title of Szirtes’ 2004 T.S. Eliot prize-winning collection is an allusion to the predominance of the rolling, unravelling impact of his majestic terza rima. By this stage, there is a greater ease to the looping to and fro, the past and present, which Szirtes encompasses in this form.

Here I find bits of my heart. In these

Dark corridors and courtyards something true

x

Survives in such obsessive images

As understand the curtains of the soul

Drawing together in the frozen breeze.

(‘Reel’)

‘Sheringham’ also reinforces Szirtes’ familiar cumulative techniques remarking on the “boiled down particulars that regularly come / knocking at the skull”. Sonnets too continue to be a favoured form, though in the beautiful meditation on the aging processes, ‘Turquoise’, the neatly closing couplet of the “Shakespearian ending” is both employed and simultaneously questioned.

Indeed, echoes of the Bard’s obsessive negotiations with “swift-footed Time” (XIX) re-emerge as one of the most striking features of Szirtes’ more recent poems. A pizza can be enjoyed – but not to the exclusion of the river nearby, an unavoidable “emblem of time” (‘In the Pizza Parlour’). Szirtes is re-visiting the concerns of younger days from more slant-lit uplands. Now images of dust recur, here in the woman’s “dust-laden hair” while elsewhere birds are “swimming through dust” (‘Winter Wings’) and – in one of Szirtes’ most beautiful sonnets – a woman regards herself in the mirror, contemplating the impact of the passing years and gazing at her face “drowned in a cloud of dust: / How beautiful, she thought, and how unjust” (‘The Breasts’).

![DKKnm3zX0AAbJg_[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/dkknm3zx0aabjg_1.jpg)

![Lee-Miller[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/lee-miller1.jpg)

![Collaborators[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/collaborators1.jpg)

![486434472_f02117992d_o[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/486434472_f02117992d_o1.jpg)

![Saphra-interview[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/saphra-interview1.jpg)

![lee_miller_biography_beautiful_young_thing_audacious_muse_photographer_3l[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/lee_miller_biography_beautiful_young_thing_audacious_muse_photographer_3l1.jpg)

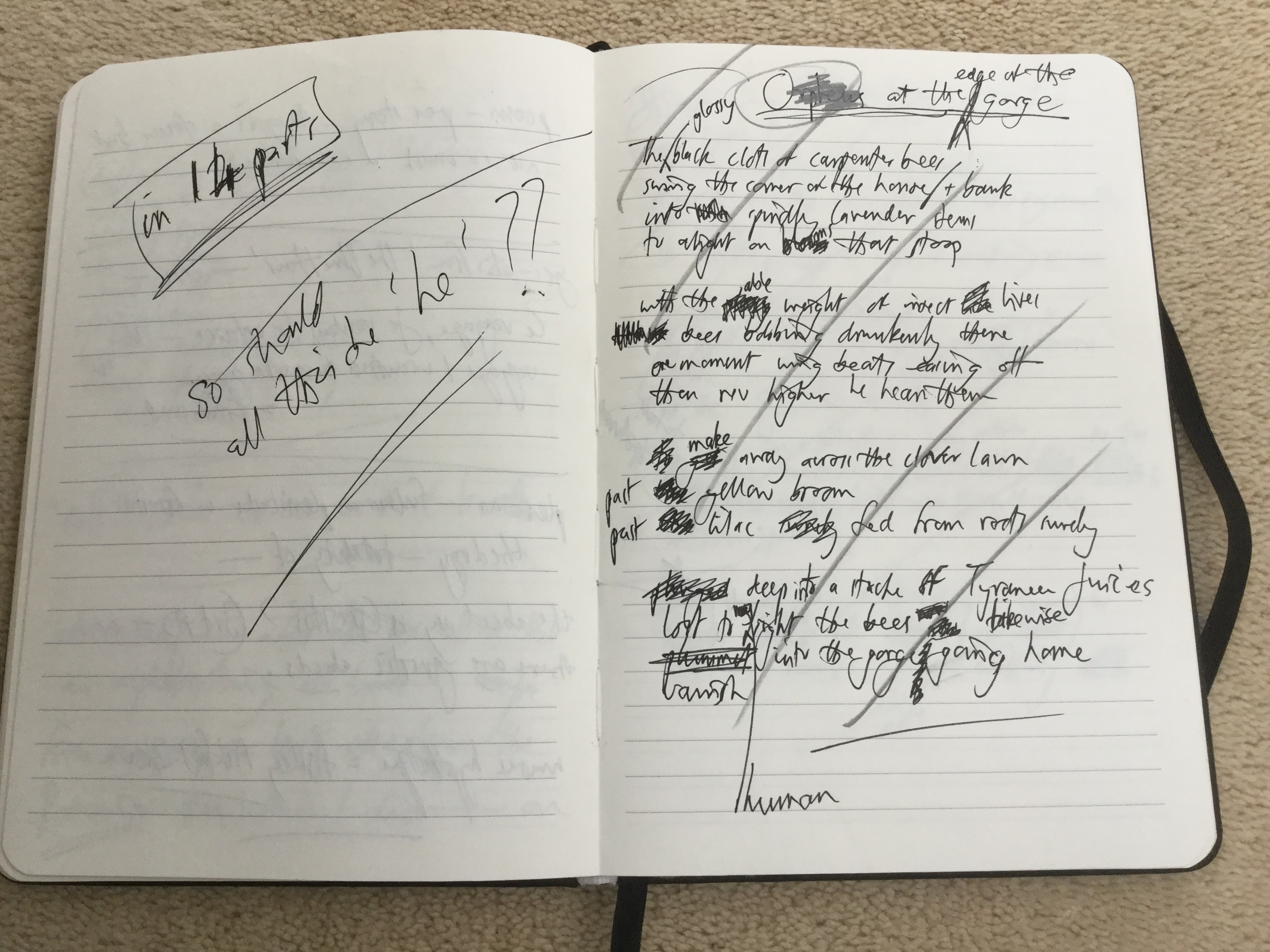

The poems move from one image to the next but there are the same preoccupations – the specks and the flocks and movements alongside monuments and geology – contrasting contexts of time, and the sense (especially given the form) of something trying to be ordered or sorted out, but not quite complying – “dicing segments of counted time…” The diagrammatic, map-like – but not-quite scrutable imagery is a response to this – an attempt to make sense of forms and information, or grasp a particular memory and note it down. Not quite successfully. We are left with a string of related thoughts and a measuring or structuring impulse.

The poems move from one image to the next but there are the same preoccupations – the specks and the flocks and movements alongside monuments and geology – contrasting contexts of time, and the sense (especially given the form) of something trying to be ordered or sorted out, but not quite complying – “dicing segments of counted time…” The diagrammatic, map-like – but not-quite scrutable imagery is a response to this – an attempt to make sense of forms and information, or grasp a particular memory and note it down. Not quite successfully. We are left with a string of related thoughts and a measuring or structuring impulse.