Please Note: this blog and website are now captured and preserved at the UK Web Archive held at The British Museum. Many thanks to them.

The highlight of last week was attending Durs Grünbein’s reading at The Goethe- Institute, where he was in discussion with his English translator, Karen Leeder. At the beginning of the evening, Grünbein joked that he’d not been in the UK for a few years and this was the first time he’d had to produce his passport (the blessings of Brexit). Interestingly, in the light of last weekend’s German election results, Grünbein has often been described as a poet of the reunified Germany, having been born in Dresden and now living with his family in eastern Berlin. Grünbein’s poetry is witty, wry, perceptive, and influenced by a broad range of literary texts and often presents the disillusionment of having grown up in East Germany and explores Germany’s identity in post-Cold War Europe. He has been very vocal in recent years on the issues of immigration and the defence of Ukraine. Helen Vendler commented on the ‘sardonic humour, the savagery, the violent candor—all expressed in lines of cool formal elegance’ and Philip Ottermann, in The Independent, noted ‘Grünbein loves to jump from one register to another—one moment he is the street poet of Berlin, the next … all marble and ancient philosophy’.

Grünbein’s earlier poems were translated into English by Michael Hofmann and published in Ashes for Breakfast: Selected Poems (Faber, 2005). Karen Leeder has now published Psyche Running, a selection of more recent poems from 2005–2022 (Seagull Books). During the evening, Grünbein commented on the process of those earlier translations as ‘strange’ and the results (as is Hofmann’s wont) as being very free, very sparky, and Leeder suggested there was a particular excitement in the ‘to and fro’ between author and translator to be found in them. She then suggested her approach has been rather different, perhaps a more dutiful one, still needing to make the poems ‘live’ in the target language, but also demanding a fidelity, to capture the original’s form and architecture as closely as possible. The work read during the evening suggests that her translations triumphantly achieve these goals.

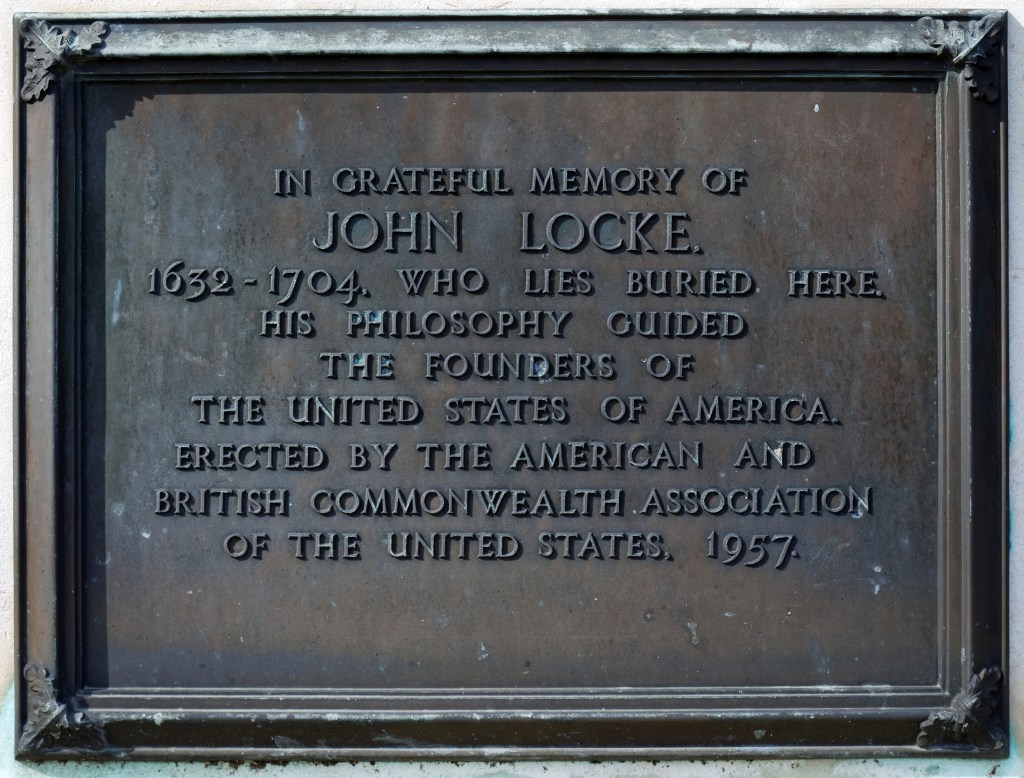

Leeder said that his work can have a ‘marble’-like quality, a firm (unbending?) Classicism, and also that he has himself been labelled a ‘poeta doctus’, given the learned, wide-ranging references he incorporates. Grünbein rather demurred at these descriptions and (an idea he repeated a couple of times in slightly different forms) any interesting poem must be the result of two steps, the first poetic, the second, a more critical, a process of reflection (a later formulation suggested the two steps were ‘perceptual’ and ‘conceptual’). These two phases result in the finished poem as ‘a form of knowledge’; Grünbein pointed out that philosophy arose out of poetry in Classical times (not the other way round). The first poem he read, ‘Childhood in the Diorama’, does have a ‘marble’-like quality to it: longish, unrhymed lines in a solid verse paragraph and the child’s preference for the posed scenes of a museum’s diorama, their ‘inert’ quality. But on one occasion, the boy sensed some movement, a ‘draught, perhaps, had blown through the displays’, perhaps suggestive of the child’s development into a more unstable, fluid view of the world.

Other poems read that evening included ‘Nee Wachtel’, ‘Exaltations in Sleep’, and ‘Inspector Kobold’ which is a ‘Martian’ sort of piece describing seahorses, in ‘their whalebone corsets, like ‘tiny ocean Lipizzaners’ (here’s an alternative translation by Michael Eskin). If we are to take Grünbein’s poems as ‘forms of knowledge’ then they certainly range widely through the natural sciences, language, science more generally, astronomy, history and politics. He felt what binds all this together is the one individual life, the single life perspective, poetry as a sort of anthropological study, at which Leeder suggested there was a ‘fragility’ to much of his work, the vulnerability of the single life as much as all life (ecologically?). The poet was happy to agree to this, suggesting ‘marble’ was not at all the right term for his poetry, that there was always something ‘flowing’ about it, multiple angles and perspectives. He once claimed not to be a ‘German’ poet, but simply someone who wrote in the German language. This evening he stood by that statement: his own identity is wrapped up in language use, the mother’s language, used daily for years, and is not a function of birthplace alone (remember Grünbein grew up in East Germany and now lives in the unified Germany).

But his birthplace has been undoubtedly important in Porcelain (Seagull, 2020), the long sequence of poems (written slowly, we learned, on the February anniversaries of the Allies’ bombing of his hometown, Dresden). I reviewed this book here, when it was published). Grünbein read 10 poems from this sequence (some poems were read only in German with the English translation projected above), other poems read in both languages. Porcelain is an elegy the poet suggested, a Classical form, longing for what is lost. Poem #7 is one of the most remarkable, another museum visit by the young poet, who’d stare at a cherry stone from the 16th century, carved with 185 tiny heads. The poem comes to regard the curious object as an ‘emblem of the future’ of Dresden, presenting as it seemed to, faces, ‘eyes wide with terror, on every tiny screaming face, / inferno on a needle tip’.

The poet suggested the whole sequence of poems is also a kind of ‘sound system’ containing echoes or samples of other poets’ work, including Paul Celan, with Grünbein’s title (Porce-lain) being a pun on the earlier poet’s name. Leeder added that it should not be read in a narrowly nationalistic fashion, that a lot more (bombed) cities than just Dresden were alluded to by the poem (Coventry, Warsaw, Odessa, Guernica). She asked Grünbein what was it that kept drawing him back to Dresden as a subject matter for poems. He thought it had something to do with the moment when he realised that his own childhood was ‘historical’, in the sense of being intimately connected to major historical events. He recalls seeing truckloads of Russian soldiers passing where he grew up, heading to the nearby Russian military barracks. This produced a sense in the young boy that much in (his) life had been determined before his arrival on the scene. In this sense, his hometown acquired a ‘mythic’ quality.

KL: You mean it was a ‘world place’?

DG: Yes – I realised it was a reference point, worldwide, its splendour and its ruins. From the city of Dresden one can draw out a lot of history, a seed point, or like a jigsaw, that can be slowly pieced together.

Perhaps half a dozen more poems were presented from more recent collections. ‘Flea Market’ is a peerless poem about German history, starting from the bric-a-brac found in such markets – the spoons, brooches, bird cages, tables – and wondering ‘what / do they say, what do they hide’? Quiet allusions to ‘uniforms and daggers of honour’, seque into the next, even more troubling, question: ‘How can one’s thoughts not go astray / faced with the piles of glasses, / and old leather suitcases?’ The poem ‘Lumière’ also alludes to the Holocaust and starts out from descriptions of the Lumière brothers’ 1896 film of a train pulling into a station. The first film-goers were frightened at the image of the train’s approach, ‘but not yet the horror / at all the implacable trains / that have criss-crossed the century, / the endless rows of sealed trucks.’

Asked where his poetry might be heading, Grünbein surprisingly suggested that he felt a more prose-like quality entering his work – not so Classical then! A soberness in some ways – but with flashes of magic, magic spells even. His earlier suggestion that the good poem is a 2-step process – perceptual, conceptual – seems to be still important, though in the final result (I’m guessing Grünbein would agree with this) the two stages must be simultaneously present in the reader’s experience.

I have to say, one of the great pleasures of the evening was the way in which both participants took the poetry seriously and gave it a good outing. This may sound odd for a poetry reading, but often these days, I find too many readings/launches contain too little poetry and rather too much gossiping, drinking and networking (all of which can be excluding for those not in the swim). Can I make a plea for more reading at readings, a little less career-building? Of course, at The Goethe-Institute we were listening to two writers at the very top of their game and what they are creating – in German and in English – is vital, lasting stuff. But, if we are publishing poetry, we should not be shy of reading it (remember, not everyone attending will be able to afford to buy the book and take it home).