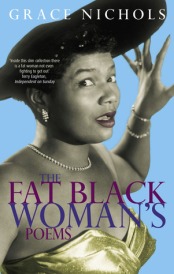

Several things coinciding . . . my last-but-one blog had Helen Mort wondering if cliché was an acceptable response to a vast and alien landscape (the Arctic) before which “linguistic originality can almost seem a little arbitrary”. Then, in the recent PN Review (May/June 2018 – No 241), there is a terrific essay by Kei Miller in which he is proposing a different kind of noise to more traditional English poetics which he characterises by using a passage from Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel, The Remains of the Day. Englishness, he argues, lies in a “lack of obvious drama or spectacle [. . .] a sense of restraint”; there is no need “to shout it”, there is a desire to avoid “unseemly demonstrativeness”. Miller goes on to explain how he found, in Grace Nichol’s 1982 collection, The Fat Black Woman’s Poems, a far noisier, more playful, more liberated and liberating kind of voice, in contrast to the (still) prevailing “critical landscape [and] reviewing discourse that continues to heap accolades and praise onto poets for their restraint and their subtlety and their quietness, not stopping nearly enough to think how such praise can be racially loaded”.

Then I have been reading poems for Grenfell Tower (The Onslaught Press) and picking away at some link between the (in)adequacy of a certain English poetic voice to confront the scale of ecological issues, or as a vehicle for expressing certain cultural differences, or as a way of exploring the kind of tragic and grievous event represented by the Grenfell fire and its aftermath. This struck me particularly as, in the Grenfell anthology, there are well-know poets alongside others less well-known, plus some who felt impelled to write as a direct result of the catastrophe. I felt many of the more well-known names struggled to find a sufficient voice for this appalling event, often sounding too careful, overly subtle, perhaps too concerned with Mort’s “linguistic originality”. Does such a devastating, large scale, well publicised event require a different kind of voice from poets?

Then I have been reading poems for Grenfell Tower (The Onslaught Press) and picking away at some link between the (in)adequacy of a certain English poetic voice to confront the scale of ecological issues, or as a vehicle for expressing certain cultural differences, or as a way of exploring the kind of tragic and grievous event represented by the Grenfell fire and its aftermath. This struck me particularly as, in the Grenfell anthology, there are well-know poets alongside others less well-known, plus some who felt impelled to write as a direct result of the catastrophe. I felt many of the more well-known names struggled to find a sufficient voice for this appalling event, often sounding too careful, overly subtle, perhaps too concerned with Mort’s “linguistic originality”. Does such a devastating, large scale, well publicised event require a different kind of voice from poets?

I hope it’s not invidious to make comments on poetic success or failure in an anthology intended to draw attention to the human victims and survivors of the fire (and through its sales to raise money for the Grenfell Foundation). The editor, Rip Bulkley, writes about compiling the anthology here. But the struggle of artists to respond to such events is worth considering because it reflects how we might respond, or find it hard to respond, or find words for our responses. MP David Lammy’s Foreword to the book says that the Grenfell Tower fire exposes a tale of two cities – one with a voice, another without. Or rather, those in power continue to be deaf “to Grenfell’s voices and voices like them”. So this anthology is just one of many efforts to speak out, encouraging its readers to listen and “bear witness” and perhaps – as Kei Miller suggests in a different context – such work needs greater volume and less quiet restraint. This is certainly reflected in the frequency with which bold repetitions and rough balladic forms are used in these poems and there is chanting too – less liturgical, more Whitehall demo, more football terrace.

The difficulties of addressing such a subject are expressed by Joan Michelson’s contribution which announces and extinguishes itself in the same moment: “This is the letter to the Tower / that I cannot write”. One of the best poems which does display evident ‘literary’ qualities is Steven Waling’s ‘Fred Engels in the Gallery Café’. It cleverly splices several voices or narratives together, one of these being quotes from Engels’ 1844 The Condition of the Working Class in England. Other fragments used allude to gentrification and the wealth gap in the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Other poems, like Pat Winslow’s ‘Souad’s Moon’, focus on the presence of refugees in the Tower, or the role of the profit-motive in the disaster (‘High-Rise’ by Al McClimens), or the presence of an establishment cover-up after the event (Tom McColl’s ‘The Bunker’).

The difficulties of addressing such a subject are expressed by Joan Michelson’s contribution which announces and extinguishes itself in the same moment: “This is the letter to the Tower / that I cannot write”. One of the best poems which does display evident ‘literary’ qualities is Steven Waling’s ‘Fred Engels in the Gallery Café’. It cleverly splices several voices or narratives together, one of these being quotes from Engels’ 1844 The Condition of the Working Class in England. Other fragments used allude to gentrification and the wealth gap in the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Other poems, like Pat Winslow’s ‘Souad’s Moon’, focus on the presence of refugees in the Tower, or the role of the profit-motive in the disaster (‘High-Rise’ by Al McClimens), or the presence of an establishment cover-up after the event (Tom McColl’s ‘The Bunker’).

But more often than not, these poets opt for more tangential routes to expression. Other disasters – such as Nero watching Rome burn, the 1666 Fire of London, the bomb falling on Hiroshima and the Aberfan disaster – prove ways in for Abigail Elizabeth Rowland, Neil Reeder, Margaret Beston and Mike Jenkins. The naivety and innocence of a child’s eye is another common device. Andrew Dixon’s ‘Storytime’ takes this approach, the child’s language and vision allowing simple but nevertheless powerful statements: “Mama don’t be afraid. Do you / want us to pray? I know what / to say. We’re both in a rocket / and we’re going away.” Finola Scott does the same with a Glasgow accent, a child staring from her own tower block home: “she peers doon at hir building, wunners / Whit’s cladding?’ A young life cut off before its full development by the fire is also the theme of two poems that refer to the death of Khadija Saye. She was a photographer who died in the blaze, whose work had been exhibited in Britain’s Diaspora Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Michael Rosen’s contribution again uses childlike simplicity and obsessive repetition – as much representing a struggle to comprehend as the gnawing of realised grief:

But more often than not, these poets opt for more tangential routes to expression. Other disasters – such as Nero watching Rome burn, the 1666 Fire of London, the bomb falling on Hiroshima and the Aberfan disaster – prove ways in for Abigail Elizabeth Rowland, Neil Reeder, Margaret Beston and Mike Jenkins. The naivety and innocence of a child’s eye is another common device. Andrew Dixon’s ‘Storytime’ takes this approach, the child’s language and vision allowing simple but nevertheless powerful statements: “Mama don’t be afraid. Do you / want us to pray? I know what / to say. We’re both in a rocket / and we’re going away.” Finola Scott does the same with a Glasgow accent, a child staring from her own tower block home: “she peers doon at hir building, wunners / Whit’s cladding?’ A young life cut off before its full development by the fire is also the theme of two poems that refer to the death of Khadija Saye. She was a photographer who died in the blaze, whose work had been exhibited in Britain’s Diaspora Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Michael Rosen’s contribution again uses childlike simplicity and obsessive repetition – as much representing a struggle to comprehend as the gnawing of realised grief:

In London W11

a school.

In the school

a room.

In the room

a chair.

A chair that is empty.

A chair that waits.

Of course, there are also poems that take a more direct approach. The role of the firefighters recurs. Christine Barton’s poem is spoken by a local teacher, remembering Fire Brigade visits to her school and the tragic irony of their trying to rescue those same schoolchildren on the night of the fire. Andre Rostant – whose steelband practiced in the shadow of Grenfell Tower – addresses the fire-men as ‘The Heroes on the Stair’. And Ricky Nuttall was one of those men. A biographical note says he has been writing for many years, “as a coping mechanism for life and an expression of self”. We can be sure he would never have wished such an occasion to write about. He does so with devastating directness and authenticity about the facts of PTSD:

The silence of death

My smoke-stained hair

A hole in my soul

That will never repair

The feeling of failure

And pride that combine

To leave me confused

And abused in my mind

My lips wet with tears

I am lost There’s no plan

Emotionally ruined

One broken man

It’s no surprise that – as a politically engaged, punk performance poet – Attila the Stockbroker gets the tone and noise level right. Most of his poem ventriloquises the uncaring voices of the Royal Borough’s council with his direct, angry protest against ‘Keeping Up Appearances’:

. . . it’s time to refurbish your building.

Not with fire doors, sprinklers and care

But with cladding to make it look nicer

So the rich can pretend you’re not there.

Perhaps the most powerful poem here is by Nick Moss. He grew up in Liverpool but now lives in London. In the light of Kei Miller asking for a noisier, less restrained poetic sound, it’s interesting that Moss’ biog note tells us he performs regularly and continues to write because “if we keep shouting, eventually we’ll hear each other.” I don’t know if ‘Minimising Disruption’ is especially autobiographical, though it sounds like it (an earlier version of the poem can be found here). In it, memories of Ladbroke Grove music shops move on to song lyrics on the subject of murderers. Then Moss describes Grenfell, directly:

There are ‘Missing’ posters plastered all round Ladbroke grove.

The faces of the missing who are not-yet-officially-dead

The poem is powerful partly because it manages to tear its gaze away from the blackened stub of the Grenfell Tower to achieve some historical perspective, not to calm and reassure but to stoke the anger it so evidently feels. The poem recalls other, older song lyrics and then a comment made by John La Rose about the New Cross fire in 1981:

‘an unparalleled act of barbaric violence

against the black community’.

I guess history teaches us to be wary

Of words like ‘unparalleled’.

However you read/judge the poems I’ve discussed and whether or not you think such a devastating, large scale, well publicised event as Grenfell requires a different kind of poetic voice, please buy a copy of this anthology – as I have said, all proceeds go to the Grenfell Foundation. Go straight to: The Onslaught Press or Amazon

PS. Myra Schneider, one of the poets included in this anthology has linked me to a later poem she wrote on this subject, published here.

.

.