I am very grateful to Ian Brinton’s and Michael Grant’s recent translation of a selected Mallarmé (Muscaliet, 2019) for sending me back to a poet who has always proved problematic for me. My natural inclination draws me more to Louis MacNeice’s sense of the “drunkenness of things being various” (‘Snow’) – his emphasis on poetry’s engagement with “things” – and his desire to communicate pretty directly with his fellow wo/man, than with what Elizabeth McCombie bluntly calls “the exceptional difficulty” of Mallarmé’s work. I appreciate that such a dichotomy seems to shove the French poet into an ivory tower (albeit of glittering and sensuous language) while casting the Irish one as too narrowly engagé, but I’m also aware that Sartre praised Mallarmé as a “committed” writer and that, despite some evident remoteness from the ‘tribe’, the French poet’s political views were both radical and democratic.

I am very grateful to Ian Brinton’s and Michael Grant’s recent translation of a selected Mallarmé (Muscaliet, 2019) for sending me back to a poet who has always proved problematic for me. My natural inclination draws me more to Louis MacNeice’s sense of the “drunkenness of things being various” (‘Snow’) – his emphasis on poetry’s engagement with “things” – and his desire to communicate pretty directly with his fellow wo/man, than with what Elizabeth McCombie bluntly calls “the exceptional difficulty” of Mallarmé’s work. I appreciate that such a dichotomy seems to shove the French poet into an ivory tower (albeit of glittering and sensuous language) while casting the Irish one as too narrowly engagé, but I’m also aware that Sartre praised Mallarmé as a “committed” writer and that, despite some evident remoteness from the ‘tribe’, the French poet’s political views were both radical and democratic.

Yet the question of difficulty remains. Proust is said to have berated Mallarmé for using “a language that we do not know” and Paul Valéry’s first encounter with the poems was also troubled: “There were certain sonnets that reduced me to a state of stupor . . . associations that were impossible to solve, a syntax that was sometimes strange, thought itself arrested at each stanza”. Yet Valéry also notes the tension between Mallarmé’s fierce semantic difficulties and his deployment of traditional form, rhyme and rich phonetic patterning; the latter inevitably suggesting that there is (or ought to be) some semantic completion in the poem. But (as J.H. Prynne comments in his Preface to Brinton’s Muscaliet translations) Mallarmé’s “flamboyant boldness, by leaps and pauses and leaps again” serves to disrupt such conventional expectations of interpretative transparency, a resolution of the many puzzles. McCombie again, writing in the Oxford World’s Classics Mallarmé: Collected Poems and Other Verses: “criticism has been dogged by an erroneous belief that such completion is recoverable”.

So, if we must give up on such ‘understanding’, what was Mallarmé – writing in the 1880-90s – doing? Something recognisably very modern, it turns out. Contra Wordsworth (and MacNeice, I guess), Mallarmé and his Symbolist peers, held ordinary language in suspicious contempt as too ‘journalistic’, too wedded to a world of facts. Poetry was to be more a communication, or evocation, of emotion, of a detachment from the (merely) everyday and a recovery of the mystery of existence which rote and routine has served to bury. Such a role demanded linguistic innovation as suggested in ‘The Tomb of Edgar Poe’ in which the American writer is praised for giving “purer meaning to the words of the tribe” (tr. Brinton/Grant). Writing about Edouard Manet’s work, Mallarmé saw the need to “loose the restraint of education” which – in linguistic terms – would mean freeing language from its contingent relations to the facticity of things (and the tedium and ennui that results from our long confinement to them) and hence moving language nearer to what he called the “Idea” and the paradoxical term Nothingness (as Brinton/Grant translate “le Neant”).

So, if we must give up on such ‘understanding’, what was Mallarmé – writing in the 1880-90s – doing? Something recognisably very modern, it turns out. Contra Wordsworth (and MacNeice, I guess), Mallarmé and his Symbolist peers, held ordinary language in suspicious contempt as too ‘journalistic’, too wedded to a world of facts. Poetry was to be more a communication, or evocation, of emotion, of a detachment from the (merely) everyday and a recovery of the mystery of existence which rote and routine has served to bury. Such a role demanded linguistic innovation as suggested in ‘The Tomb of Edgar Poe’ in which the American writer is praised for giving “purer meaning to the words of the tribe” (tr. Brinton/Grant). Writing about Edouard Manet’s work, Mallarmé saw the need to “loose the restraint of education” which – in linguistic terms – would mean freeing language from its contingent relations to the facticity of things (and the tedium and ennui that results from our long confinement to them) and hence moving language nearer to what he called the “Idea” and the paradoxical term Nothingness (as Brinton/Grant translate “le Neant”).

This latter term is a key to Mallarmé’s work. Nothingness is non-meaning, but not as “an absence of meaning but a potentiality of meaning that no specific meaning can exhaust” (McCombie, p. xii). There are Platonic, Hegelian elements here, but I’d like to understand this as alluding to what Yves Bonnefoy terms (more obviously positively) Presence. In considering both ideas, we are likely to feel some anxiety or even terror (again Mallarmé tends to accentuate the dislocation involved), simply because we are being taken beyond what is familiar. And what is familiar (both French poets understand) is largely contrasted from language use, as language is a conceptual vehicle. So the poet must re-make language and Mallarmé is much more thorough-going about this and looks, in part, to music as a non-referential model. Language must be freed from a narrowly denotative function, revelling in reflections, connections, silences and hermeneutic lacunae which simultaneously allude to, but knowingly fall short of, articulating Nothingness. Mallarmé’s use of form suggests but fails to deliver resolution in this same way, what Henry Weinfield has called a “tragic duality” at the heart of Mallarmé ‘s project.

For these reasons, Mallarmé “cede[s] the initiative to words” (‘Crise de Vers’), to language’s material aspects as much as to its referential functions. Carrying over the material aspects of his French verse into English is then, to say the least, difficult. I’m inclined to agree with Weinfield (Introduction to Stephane Mallarmé Collected Poems (Uni. Of California Press, 1994) that it is “essential to work in rhyme and metre, regardless of the semantic accommodations and technical problems this entail[s]. If we take rhyme from Mallarmé, we take away the poetry”. But is that even possible? The accommodations and problems that arise are huge! Mallarmé placed the sonnet, ‘Salut’, at the start of his Poésies as a toast, salutation and mission statement. Weinfield gives the sestet as follows:

For these reasons, Mallarmé “cede[s] the initiative to words” (‘Crise de Vers’), to language’s material aspects as much as to its referential functions. Carrying over the material aspects of his French verse into English is then, to say the least, difficult. I’m inclined to agree with Weinfield (Introduction to Stephane Mallarmé Collected Poems (Uni. Of California Press, 1994) that it is “essential to work in rhyme and metre, regardless of the semantic accommodations and technical problems this entail[s]. If we take rhyme from Mallarmé, we take away the poetry”. But is that even possible? The accommodations and problems that arise are huge! Mallarmé placed the sonnet, ‘Salut’, at the start of his Poésies as a toast, salutation and mission statement. Weinfield gives the sestet as follows:

A lovely drunkenness enlists

Me to raise, though the vessel lists,

This toast on high and without fear

Solitude, rocky shoal, bright star

To whatsoever may be worth

Our sheet’s white care in setting forth.

A concern for form and musicality throws up problems like the near-identical rhyme (enlists/lists), the choice of ‘lists’ which underplays the dangers envisaged, the adjectival filling out of the toast line itself and the final line’s inversion and convolution. I prefer Brinton/Grant’s more flexible approach, lowered register (with some humour) and half rhymes:

A beautiful intoxication urges me

With no fear of keeling over

To stand and raise a glass

To solitude, rocky shore and star

And whatever else was worth

Hoisting our white sail for.

Mallarmé’s sonnet, ‘The Tomb of Edgar Poe’ opens roundly and clearly in Brinton/Grant’s translation: “As if eternity at last transfigured him into himself’ where Weinfield again inverts and clogs the line: As to himself at last eternity changes him”. The poem ends with the wish that Poe’s granite tomb might mark an end to the disparagement (blasphemy in Mallarmé’s mind – the many attacks on Poe himself) of poets by the generality, “the tribe”. Though Brinton/Grant’s translation is a bit rhythmically inert, both Weinfield’s and E.H. and A.M. Blackmore’s Oxford World Classics translations groan under the constraints of rhyme and metre. Here are all three:

Let this same granite at least mark out a limit for all time

To the black flights of blasphemy scattered through the future. (Brinton/Grant)

Let this granite at least mark the boundaries evermore

To the dark flights of Blasphemy hurled to the future. (Weinfield)

.. this calm granite, may limit all the glum

Blasphemy-flights dispersed in days to come (Blackmore)

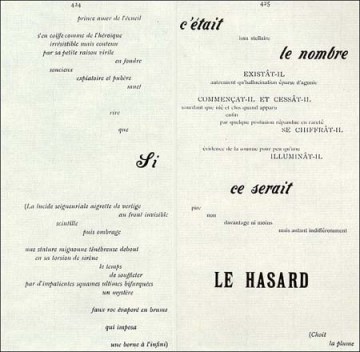

Famously, Mallarmé took his concern for the material aspects of language (hence to the placing of words, the white spaces between them) to stunning extremes. He gradually dropped most punctuation and ‘Un Coup de Dés (‘A Roll of the Dice’ tr. Brinton/Grant) spread the text across two pages with variations in both font and size, to create something more akin to a musical score (see image below). In his own Preface, he explains how the white spaces of paper “take on some importance . . . The paper asserts its presence every time that an image comes to a halt and vanishes before accepting the presence of its successors” (tr. Brinton/Grant). The result is that the “fictive reality” of language is endlessly sinking and surfacing into/out of the white of Nothingness. We read a musical score evoking the struggle (imaged as another sea voyage) between our efforts to make conceptual sense and our glimpses and intuited (?) accesses to “a potentiality of meaning that no specific meaning can exhaust”.

As words reach for meaning, so it slips away and so we are intended to experience both the attempt and the plenitude of what is lost . . . I think. I don’t know that I DO experience anything like this in reading Mallarmé – my limitations too often leave me with something more like Valéry’s “state of stupor”, a sort of numbness (and a headache), a sense of my own falling short. My French is not really good enough to ‘enjoy’ the original poems, so I must depend on translation and, happily, those by Ian Brinton and Michael Grant have helped me move a notch or two along the road towards appreciating Mallarmé’s still extraordinary work.

Displaying his characteristic flair, craft and intelligence, Crucefix’s poems often begin with the visible, the tangible, the ordinary, yet through each act of attentiveness and the delicate fluidity of the language they re-discover the extraordinary in the everyday.

Displaying his characteristic flair, craft and intelligence, Crucefix’s poems often begin with the visible, the tangible, the ordinary, yet through each act of attentiveness and the delicate fluidity of the language they re-discover the extraordinary in the everyday.

I

I In lieu of a new blog post, here is a link to the Hercules Editions webpage on which I have formulated a few thoughts about the current lockdown, photography and the (forgotten?) refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. It is a piece in part related to the Hercules publication of my longer poem,

In lieu of a new blog post, here is a link to the Hercules Editions webpage on which I have formulated a few thoughts about the current lockdown, photography and the (forgotten?) refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. It is a piece in part related to the Hercules publication of my longer poem,

This is Walford Davies’ fourth book from Seren and it is an ambitious project, combining narrative and lyric form (every poem is 16 lines long, in unrhymed couplets, most in four beat lines). It’s also a dramatic monologue, in effect, as the speaker is a thoroughly unpleasant, arrogant, but haunted architect engaged in several large urban projects in Cardiff between the years 1890 and 1982. Talk about the male gaze, this man epitomizes it. He and his wife have recently buried a child lost in stillbirth (“they wrapped it in a pall // not bigger than my handkerchief”) and while she mourns the loss, he gets on with his work and frequents bars and prostitutes in Cardiff’s docklands. The sympathetic reader is probably going to try to read this man’s cruel and dismissive treatment of his wife (and his exploitative relationships with other women) as his own rather twisted way of dealing with grief. But it’s hard to maintain that view, as Walford Davies is often shockingly good at catching his loathsome attitudes, especially towards women: “This quarter grows on me. / In shabby rooms in Stuart Street // my new friend swears // she’ll tackle anything for oranges”.

This is Walford Davies’ fourth book from Seren and it is an ambitious project, combining narrative and lyric form (every poem is 16 lines long, in unrhymed couplets, most in four beat lines). It’s also a dramatic monologue, in effect, as the speaker is a thoroughly unpleasant, arrogant, but haunted architect engaged in several large urban projects in Cardiff between the years 1890 and 1982. Talk about the male gaze, this man epitomizes it. He and his wife have recently buried a child lost in stillbirth (“they wrapped it in a pall // not bigger than my handkerchief”) and while she mourns the loss, he gets on with his work and frequents bars and prostitutes in Cardiff’s docklands. The sympathetic reader is probably going to try to read this man’s cruel and dismissive treatment of his wife (and his exploitative relationships with other women) as his own rather twisted way of dealing with grief. But it’s hard to maintain that view, as Walford Davies is often shockingly good at catching his loathsome attitudes, especially towards women: “This quarter grows on me. / In shabby rooms in Stuart Street // my new friend swears // she’ll tackle anything for oranges”. Walford Davies, in an end note, talks of the ambiguity of the female figures – wife, prostitutes, dead girl – who do tend to float without clear identity, disembodied, through the text. It adds something to the ghost-like quality of the book, but the loss is any more powerful evocation of them. Also, the choice of brief lyrics to develop what could well have been a novel, gives the reader some powerful moments but few prolonged engagements with any of the characters. And the nature of the central male figure is problematic because of his downright unpleasantness (though, I suppose, Browning managed it in ‘My Last Duchess’) and in 2020 there will be plenty of readers who find such a portrayal an absolute bar to reading. I don’t think Walford Davies ironises and critiques his male figure enough, or clearly enough.

Walford Davies, in an end note, talks of the ambiguity of the female figures – wife, prostitutes, dead girl – who do tend to float without clear identity, disembodied, through the text. It adds something to the ghost-like quality of the book, but the loss is any more powerful evocation of them. Also, the choice of brief lyrics to develop what could well have been a novel, gives the reader some powerful moments but few prolonged engagements with any of the characters. And the nature of the central male figure is problematic because of his downright unpleasantness (though, I suppose, Browning managed it in ‘My Last Duchess’) and in 2020 there will be plenty of readers who find such a portrayal an absolute bar to reading. I don’t think Walford Davies ironises and critiques his male figure enough, or clearly enough.