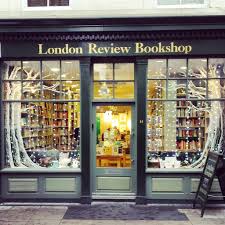

Last Friday night I read briefly (partly from my Worple Press book: https://martyncrucefix.com/publications/a-hatfield-mass/) at the LRB bookshop, 14 Bury Place, London WC1A 2JL (in fact just doors along from Enitharmon Press’ new offices). It was the launch of Magma magazine’s new issue (http://magmapoetry.com/). Magma really has become one of the must-read magazines in UK poetry and the event was one of two national launches (the other is on Thursday 11 December at 7pm at the Lit & Phil, 23 Westgate Rd, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 1SE, with guest reader Sean O’Brien). The LRB is a spectacularly good bookshop but you feel acutely the vanishing of bookshops elsewhere – to be surrounded by shelves of ‘proper’ books is a real pleasure, distressingly beginning to take on the quality of a sepia-tinted memory. Yet, as one of the readers commented, this is a dangerous place to visit if you’re not prepared to part with hard cash: so many temptations. It’s also a good place for a reading: chairs from front to back on the ground floor, seating well over 50, and on Friday it was packed.

Magma 60 is edited by Rob A. Mackenzie and Tony Williams (one of the good and distinctive things about the magazine is its rolling editorship) and 19 poets were asked to read a couple of poems each, with Kei Miller putting in a longer shift at the end as guest poet. Among others, Peter Daniels’ poems evoked a quiet, desperate sense of things not holding, of wider societal failing (‘you might discover you’re painting the house / while the other side’s on fire’). Jacqueline Saphra remembered being seventeen and then dealing with her own seventeen-year olds, boys and girls, the latter crying from their rooms, ‘Come in, I won’t let you in, Come in’. Michael Henry recalled Finals exams and wanting to write about Brecht, which he does in his poem ‘Agent provocateur’: ‘The Brechtian grape is a dry white grape / and it tastes like the white corpuscles in blood’. Martha Sprackland and Jasmine Simms found common ground and a source of poetry in drifting off in science classes at school (I remember it well).

John Greening read about visiting the archaeological dig at Sutton Hoo and an intriguing poem about ‘The Battle of Maldon’ which knowingly fails to offer ‘an explanation // of what happens in the end [. . .] about how whatever it is was broken’. DA Prince also evoked an earlier age with ‘The bell-makers’ reminding me of sequences from Tarkovsky’s film Andrei Rublev (1966): ‘the brilliant blistering light, / that cataract of blazing air, the stream / of liquid pain’. Karen Leeder presented new translations of German poet, Volker Braun. Braun was writing in part through the upheavals of 1989, exploring the triumph of capitalism: ‘EVERYTHING AND NOTHING / Was it ever really yours? Fuck you, fantasist. / The encore: all that you could never need!’ (http://www.amazon.co.uk/Rubble-Flora-Selected-Seagull-German/dp/0857422189/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1417365225&sr=1-1&keywords=volker+braun).

At the end of the first half, Gwen Adshead, a forensic psychiatrist and psychotherapist who works in secure hospitals, talked about her work and love of Philip Larkin’s poetry and read ‘Talking in Bed’ (one of my own Larkin favourites; see below). Kei Miller’s live delivery illuminates and energises his own words on the page. I’ve written more about his prize-winning The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion (Carcanet) on this blog (https://martyncrucefix.com/2014/10/22/kei-millers-cartographer-and-friels-translations/). He read several of the Place Name pieces, the poem where the Cartographer asks for directions and gets indirections instead (‘all true’ Kei said), the ‘Hymn to the Birds’ and the 28,000 rubber ducks poem which moves (almost imperceptibly) from children’s bath toys to captives lost overboard on trans-Atlantic passages years ago. Miller finished with his short poem ‘Distance’ which seemed to be something of an answer to Larkin’s poem chosen by Gwen Adshead; here are the two of them. . .

Talking in bed

Talking in bed ought to be easiest,

Lying together there goes back so far,

An emblem of two people being honest.

Yet more and more time passes silently.

Outside, the wind’s incomplete unrest

Builds and disperses clouds in the sky,

And dark towns heap up on the horizon.

None of this cares for us. Nothing shows why

At this unique distance from isolation

It becomes still more difficult to find

Words at once true and kind,

Or not untrue and not unkind.

Distance

Distance is always reduced at night

The drive from Kingston to Montego Bay is not so far

Nor the distance between ourselves and the stars

And at night there is almost nothing between

The things we say, and the things we mean.