Up-dated December 2015

Terry Gifford’s Cambridge Companion to Ted Hughes is a fantastic summing up of where Hughes’ reputation now is, including articles by various hands on Hughes and animals, Plath, myth, feminism (it’s complicated) and a clear account of the poet’s fascination with Shakespeare by Jonathan Bate.

Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love – a book I’ve intended to read for decades and though I baulk at much of it still I love her focus on the visions taking place in “an ordinary, household light”, her vivid descriptions and tentative, undogmatic prose. She also boldly talks of Christ as our mother: “Who showed you this? Love. What did he show? Love. Why did he show it to you? For love.”

Few poets can travel such distances with such ease and brevity as Penelope Shuttle. I saw her read at the recent Second Light Festival in London and picked up her Templar Poetry chapbook, In the Snowy Air. It belies it’s rather Xmas-y title by being rather a hymn to London (with occasional snow showers) including the Shard, the Walbrook, the British Library and even Waitrose in Balham.

Hands and Wings: Poems for Freedom for Torture has been edited by Dorothy Yamamoto in support of the Freedom from Torture charity and includes work by Gillian Allnutt, Alison Brackenbury, David Constantine, Carrie Etter, Vicki Feaver, Pippa Little and Susan Wicks.

Up-dated November 2015

With the cold weather coming, Yves Bonnefoy’s 1991 Beginning and End of Snow(Bucknell University Press, 2012) is an exquisite read in Emily Grosholz’s translation, including an original essay by the poet on ‘Snow in French and English’.

I’m convinced Bonnefoy’s response to snow is not a million miles distant from the Daoist idea of the uncarved block and Rudolph G Wagner’s second magnificent volume on Wang Bi’s A Chinese Reading of the Daodejing is full of insights through its literal readings of the 81 chapters. I have been comparing his readings with my own new versions before going to press in the next few weeks.

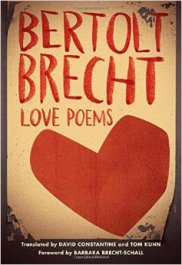

Bertolt Brecht: Love Poems (Norton, 2015) is the first instalment in David Constantine and Tom Kuhn’s project to translate anew Brecht’s complete poems. Ranging from the delicate, literary, erotic and plainly pornographic, here’s yet more evidence (should we need it) of Brecht’s breadth as a poet. The Introduction also reveals that Brecht refused to award any prizes in a poetry competition he was asked to judge – because none of the poems successfully communicated anything of any value to anybody, they were all of no use.

Maggie Butt’s new collection is published by The London Magazine and contains work from the period in which she also published the themed books Ally Pally Prison Camp(Oversteps, 2011) and Sancti-Clandestini – Undercover Saints (Ward-Wood, 2012). Though miscellaneous in nature, it is time that dominates this book – historical time in a variety of European locations and personal time in several moving elegies and acts of remembrance.

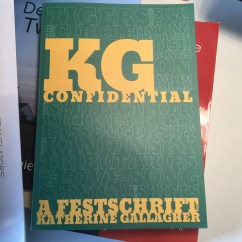

KG Confidential: a festschrift for Katherine Gallagher is a wonderful tribute to one of the great movers and shakers in poetry (in London and in her native Australia and in translation from the French). These tributes of poems or prose include contributions from Liz Berry, Jane Duran, Kate Foley, Mimi Khalvati and Les Murray.

Up-dated October 2015

Alan Brownjohn’s new book is full of excellent poems, several of which (a few decades ago) would have been designated ‘secret narratives’. The title poem, ‘A Bottle’, is a strange noir thriller set in some undefined coastal region, an enigma of messages, relationships, landscape and murder. Always surprising; no let up in vigour and inventiveness.

Kate Foley’s ‘The Don’t Touch Garden’ (Arachne Press) is a treatment of adoption to rival Jackie Kay’s ‘The Adoption Papers’. “Mirror, mirror, on the wall” the old joke says, “I am my mother after all”. But which one? Brilliantly focused and carefully sequenced, these poems provide a thrilling and moving account of the processes by which any of us – adopted or not – become who we are.

Agenda’s ‘Family Histories’ issue has poems from Tony Curtis, Claire Crowther, Sean Street, Peter McDonald, Sheenagh Pugh, Maitreyabandhu and Danielle Hope, an interview with Robin Robertson and reviews of Abse, Hugo Williams, Sebastian Barker, Bryce, Liardet, McVety and Eilean Ni Chuilleanain.

The new issue of Stand has tributes to the late John Silkin from John Matthias and Anne Stevenson. I remember seeing Silkin selling Stand in the late 1970s on the campus at Lancaster University. This issue also has new poems from Muldoon, Mort, Valerie Jack, Sam Gardiner and (even) Martyn Crucefix.