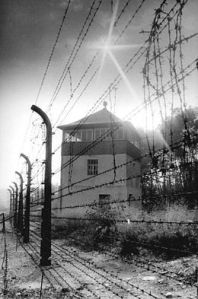

Last week, the 27 January 2015 marked the seventieth anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp. I have only once tried to address the subject – in a poem dedicated to my father who served in WW2 in the RAF, mostly in the deserts of Egypt (he was with 80 Squadron: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No._80_Squadron_RAF).

He was an engineer by trade and – as far as I know – saw no hand to hand combat. His brief was to maintain the Hawker Hurricanes that were a major component of Allied air power in North Africa. The poem records his only war injury: badly burned legs from jumping too quickly onto the nose of an aircraft after it had landed, straddling its still blisteringly hot twin exhausts. In the 1960s, he’d tell us about this while we sat at the dining table gluing together Airfix models of Hurries (as he calls them), Spits and Lancs.

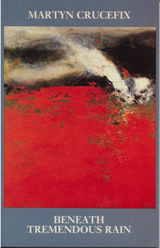

The poem was finally published in 1994 in On Whistler Mountain (see https://martyncrucefix.com/publications/on-whistler-mountain/) It opens with a less than complimentary picture of my father’s unreconstructed political and racial views which I wanted to link to the birth of Christ and the Holocaust. Ironically, given his attitude to people of colour, my father dreams in the poem that he is one of the Magi, Caspar, often depicted as a King from the Indian sub-continent. The poem’s narrative folds over to encompass both the first stirrings of Caspar’s dream about the birth of Christ as well as his last days which I imagine him spending in northern Europe.

Being a King of sorts, my-father-as-Caspar imagines the birth of a conventional king, one of conventional powers, but the child’s family turns out to be of no “consequence”. The child he finds in Bethlehem (I was thinking of course of T S Eliot’s ‘Journey of the Magi’) seems little more than a “futile gesture”. More dreams – which the poem takes as shorthand/short-cuts to the life of the imagination – then drive Caspar north to settle in northern Europe, himself facing racist attitudes among the native peoples there.

My father’s imagined bafflement before this strange dream in which he plays the role of a non-white king is – I’m sure now – partly his son’s liberal conscience obliquely criticizing his politics. My poem leaves Caspar to die in the northern forests, himself bewildered by what his own dreams have driven him to. The Christ child he dismissed years earlier, continues to visit him in dreams where he goes weeping over that “precise, god-forsaken ground”. The visionary child sees into the future, is a prescient witness to his own Jewish people rounded up by the Nazis’ similarly repellent attitudes to power and racial difference, finally entering “incinerators smoking in the German forest”. Of course, Auschwitz itself and many other camps were not built on German soil, but it was important to use the ‘G’ word at the end of the poem. In the strict pursuit of truth, I was imagining Caspar’s long-house on German soil in the locality of Dachau or Buchenwald, the name of the latter translating as ‘beech forest’.

A Long-House in the Forest

for my father

1.

His war happened in the blazing Middle East.

When he was young, far from the mud of Europe

and the wired camps, his thighs were burned

by too much bravado, sitting astride

the exhausts of a Hurricane that hadn’t cooled.

He picked up the language. Never liked Arabs.

Any dark skin’s still a nigger to this day.

So he votes for the Right, though he’s careless

of politics and takes it as read: we all

long for power and we all need to be led.

2.

In his dream, he is Caspar. He has chosen

to wait in the draughty long-house, watching

the yard collect its ragged slush of leaves.

He knows the corn-bins are flooded and rotten.

He knows this month is the anniversary

of nights when Caspar rolled in distress, youth,

dream illumination – an excited showing

of power’s open hearth, its air-gulping fire –

his sleep filled with the birth of a king

whose strong arm would invigorate the world.

At once, Caspar instructed a journey. His gift

for this new king, of course, was gold.

3.

A wretched child asleep on that year’s straw.

Neither mother nor father people of consequence,

but simple Jews – trouble-making, deluded.

This was nothing worth his understanding.

(He knows Caspar is a man of wisdom and books).

What could be the need for this powerless figure?

Why this pot-bellied brat? This futile gesture?

Shepherds stood with doting faces for the boy.

He turned his back, dropped the derisory gift.

4.

Without wishing, Caspar gleaned what became

of the lad from travellers’ unlikely tales.

How he saw no reason to cloak humility.

Nor saw the need to make a show of strength.

No surprise the authorities destroyed him.

And on that day, Caspar, his dream-self,

was driven by dreams again, north this time,

to the Black Sea, fighting the Danube inland,

to this blond-haired, beer-drunk, long-limbed place,

whose people mistake him for a piece of Hell

with his blackened face and barbarian tongue.

5.

Sitting by the squadron’s crest, a photograph

of the kids, he sees no reason to dream himself

black and ignorant, plagued by dreams. But he is

Caspar, has chosen the long-house and struggles

at night – not with dreams of the hot south,

of home, courtyards, frescoes and fountains-

but with a dream that has no place yet, though

he searches for it, now that same, futile boy

in the straw has grown his only dream-guide

and weeps over this precise, god-forsaken ground.

He finds it ruled by those whose failure is to see

no need for an icon of the weak, the needful.

Here, the boy’s deluded people prove no trouble at all,

filing from wooden huts ranged like inland galleys,

to incinerators smoking in the German forest.