This is the fifth and final installment in the series of reviews I have been posting of the collections chosen for the 2016 Forward Prizes Felix Dennis award for best First Collection. The £5000 prize will be decided on 20th September. Click here for all 5 of my reviews of the 2015 shortlisted books (eventual winner Mona Arshi).

The 2016 shortlist is:

Nancy Campbell – Disko Bay (Enitharmon Press) – click here for my review of this book

Ron Carey – Distance (Revival Press) – click here for my review of this book

Harry Giles – Tonguit (Freight Books)

Ruby Robinson – Every Little Sound (Liverpool University Press) – click here for my review of this book

Tiphanie Yanique – Wife (Peepal Tree Press) – click here for my review of this book

Thanks to Freight Books for providing a copy of Harry Giles’ book for review purposes.

I’d only come across Harry Giles’ work as a Guardian featured poem in June in response to his Forward short-listing. The chosen poem was ‘Piercings’ and suggested Giles was working the same area that Andrew McMillan did so successfully last year. What might be an autobiographical masculine narrative voice recognises a passer-by as an old encounter: “four years since / he hauled me into a lift with / Want to make out?” But the man had then been sporting various body piercings which have since been removed in order to become “employable, less obvious” whereas the narrator has continued making “more holes”, continued to accumulate the badges of a rebelliousness the other has given up on. The final question, “So what do you do now?” is therefore made poignantly redundant, each, surely, reading the tell-tale signs of the other’s body.

But ‘Piercings’ is by far the most conventional poem in Tonguit and Giles is no McMillan, nor does he want to be. On the facing page is a poem made from extracts from One Direction’s Harry Styles’ fanfiction. The title, ‘Slash poem in which Harry Giles meets Harry Styles’, gives a feel for its playfulness though the poem itself does not seem to amount to much. Perhaps it amounts to more if read in the context of Giles’ other manipulations of texts and discourses which have a more obviously seditious intent. The last poem in the collection offers ‘Further Drafts’ of a phrase often used by Alistair Gray: “work as if you live in the early days of a better nation”. Giles works various rhyming turns on the first and last words of this phrase eventually to arrive at “lurk as if you live in the early days of a better sedition”. It’s ‘Harry Styles’, manufactured pop idol and X Factor/Simon Cowell cash cow, that is the real target of Giles’ poem (though it lurks with some seditious intent, it’s still not among his best).

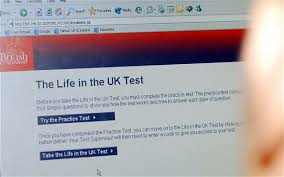

Giles is interested in the processing of texts, sampling from George R R Martin’s A Game of Thrones, or creating cut-up texts from information associated with Abu Dhabi’s artificial island and cultural centre, ‘Saadiyat’. The satirical effects are delivered through simple repetition and disjunction, questioning the original source’s coherence and integrity, where ecological sustainability becomes “a core value integrated into the design approach / in terms of throughout the the the concept design” [sic]. ‘You Don’t Ever Have to Lose’ does something similar with advertising text from IT services company Atos. ‘Your Strengths’ is a more powerful text in its own right, this time using source material from the Department of Work and Pensions Capability Assessment, the UK Citizenship Test and other psychometric tests to make a thunderous barrage of questions ranging from the invasive, absurd, profound, squirm-inducing and piddling to the politically loaded. Giles also works textual legerdemain in ‘Sermon’, based on a speech by David Cameron in which the word “terrorism” is replaced by the word “love”:

We must make it impossible

for lovers to succeed. We need to argue

that love is wrong. To belong here

is to believe in these things.

This processing of texts, often randomly, often derived from the internet or Google searches, sometimes with editorial influence in the final result is presented as politically subversive. As the Tonguit blurb suggests, it derives from the belief that we are all warped and changed by the language/s that surround us and inhabit us. The hope of the lyric poet working towards his/her own truth is devalued, considered delusional, impossibly bound up in Blake’s socio-psycho-political “mind-forged manacles”. We liberate ourselves by breaking these, unpicking or smashing the dominating discourses around us. And if our deliberate intention is already suspect then we must achieve it randomly, perhaps via a machine. It’s a form of surrealism which profoundly questions our use of language and owes a lot to the Oulipian experiments of Raymond Queneau. Giles’ collection title, Tonguit, productively seems to hover between an urgent imperative to individual vocalisation – tongue it! – and more passive implications about the way other people’s language/s oppress the individual – we have been tongued!

The more imperative mood is obvious in ‘Curriculum’ which takes aim at normative education and gives it both barrels:

Mix me a metaphor of noble gases,

economic engines and avant-garde

taxonomies, with Kingdom Phylum Order

gone to bloody Dada. Get down and dirty

with transects, quadrants.

There is a Wildean element to this sort of systematic over-turning though there is no doubt about Giles’ seriousness beneath the often funny, ludic quality of these poems and there is none of Wilde’s self-regarding quality. Harry Giles himself – as a recognisable, recurring, coherent, autobiographical figure – is curiously absent from most of these poems though I don’t doubt the sincerity of a poem like ‘Waffle House Crush’:

I’ll have you smothered n covered

diced n peppered n

capped n lathered n

lustred n smoothed n

spread

Giles’ various linguistic masks don’t hide so much as free him into more liberated forms of expression. I’ve deliberately not yet mentioned his most obvious, deliberately chosen mode of expression: what he calls his own “mongrel and magpie” form of Scots. Dave Coates has pointed out that, as in Kathleen Jamie’s The Bonniest Companie, Giles provides no glosses in the book on his particular Scots, “an implicit assertion of the language’s place within the broader spectrum of Englishes”. Giles’ Scots sets itself deliberately against discourses like those of the DWP and Atos as a declaration of variousness. Nor is he averse to something like a declaration of war:

Let’s be arsonists. Let’s birn the year.

[. . .]

Let’s mak like airtists

n birn the leebrars [libraries] acause we shoudna, n birn

Pairlament acause we shoud.

What follows is an apocalyptic conflagration of all things, down to the “thocht o fire”.

But the sheer vigour of Giles’ intent means his Scots is a lot harder to follow than Jamie’s. In fact, he does provide his readers with a full gloss/translation on his website. I needed this to be honest to deal with a lot of the Scots text, though the ‘translations’ then read as somewhat awkward, watered down versions of a quite different language (rather than a form of English). But it is worth the effort to really appreciate the tour de force of national- and self-assertion that is ‘Brave’. Like some Highland Whitman, making himself and his nation through singing (I’m losing some of the lay-out here):

A sing o google Scotland

o laptop Scotland,

o a Scotland sae dowf on [dulled by] bit-torrentit HBO

drama series n DLC packs fer

paistapocalyptic RPGs

But also the Scotland “whit chacks the date o Bannockburn on Wikipaedia” and fears “o wan day findin oot / juist hou parochial aw hits cultural references mey be”. ‘The Hairdest Man in Govanhill’ takes all the clichés that phrase might suggest and instead describes a man who “has thay lang white scairs on / baith sides o his mooth fae smiling that damn wide” (my italics). This is of a piece with the Cameron subversion as we hear that the man is “that bluidy haird he’s a hairt tattoed wi Dulux on his bicep n aw hit says is A LUV YE”. There’s a risk of this getting as caricatured as the cliché it intends to subvert but Giles’ Scots is put to terrific seditious intent in ‘Tae a Cooncillor’ – a kind of one-sided flyting in which the local councillor who wants to close down a swimming pool is mocked mercilessly:

Wee glaikit, skybald, fashious bastart,

whit unco warld maks ye wir maister?

Whit glamour has ye risin fest as

projectile boak?

Hit’s time tae gie yer feechie fouster [nasty fester]

an honest soak.

This is committed, bolshie, rebel-script done with great skill and immense energy but Harry Giles is too interested in too much to settle merely for this. I was interested in his Scots (or rather specifically Orcadian) versions of a few chapters of the Laozi’s Daodejing. He astutely titles these ‘Aald rede fir biggin a kintra’ [Old advice for building a country] again recalling Alistair Gray’s dictum. The opacity of the language makes Giles’ versions a hard read but (if I may) here’s his boldly economical version of chapter 53 (some indentations lost here again) followed by my own recently published version:

53

a bit wittins

whan waakan the wey

are a rod tae dree

the wey is snod

an fock cheust fancy the ramse

govrenment divided

sheens growen-up

kists empie

but heidyins’ claes are braa

thay’ve barrie blads

are stecht wi maet

gey rowthie

caa this the darg o reivers

an no the wey

Crooked avenue

chapter 53

—perhaps you have begun well

one step after another along the way

yet you walk in fear of side-tracks

the great way running level and plain

still who can resist those side-tracks

soon as good governance is in place

we’re liable to neglect our business

too soon the tall barns lie empty

sooner wear fashionable clothes heels

daggers for glances glut on food and booze

have more than we can sensibly use—

dawn breaks on some crooked avenue

what was it happened to the way

Tonguit is a bubbling cauldron of a book, willing to take risks that don’t always come off, but guided by a belief in the need to challenge the assumptions and languages of the status quo. Harry Giles is a fascinating figure (go to his website here ) and his characterisation of his Scots as “magpie” is as much applicable to his multifaceted work in theatre, software, twitterbots and visual arts, all forms of “art about protest and protest about art”. Whether contemporary poetry, as in books like this one, will prove sufficiently interesting and flexible for his creativity remains to be seen.