The shortlist for the eco-poetry/nature poetry Laurel Prize 2025 has just been announced. The finalists – judged this year by the poets Kathleen Jamie (Chair), Daljit Nagra, and the former leader & co-leader, Green Party of England and Wales Caroline Lucas – are (in alphabetical order):

Judith Beveridge Tintinnabulum (Giramondo Publishing)

JR Carpenter Measures of Weather (Shearsman Books)Carol Watts

Eliza O’Toole A Cranic of Ordinaries (Shearsman Books)

Katrina Porteous Rhizodont (Bloodaxe Books)

Carol Watts Mimic Pond (Shearsman Books)

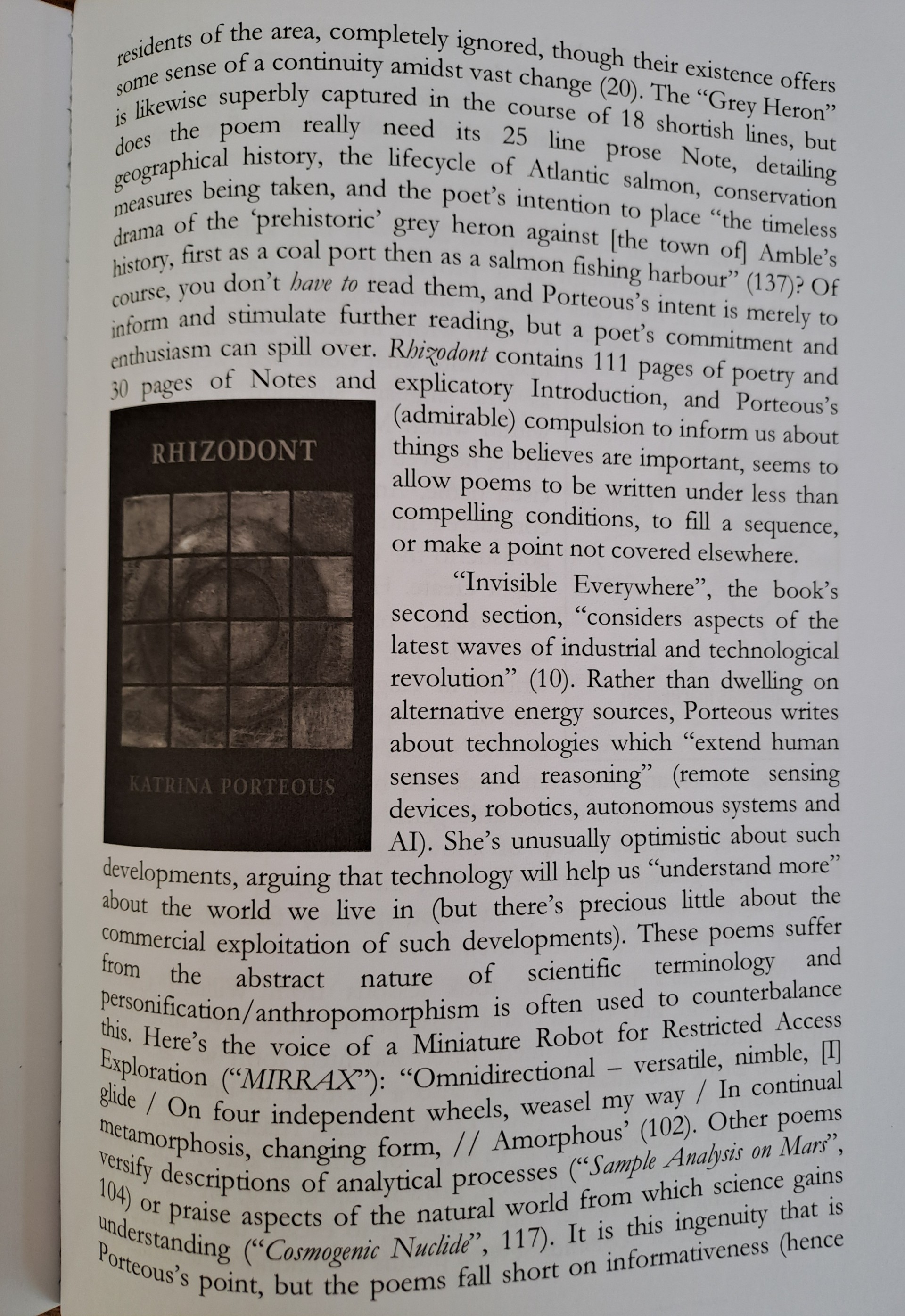

It turns out I have reviewed two of these collections – one of them I have been bending the ears of anyone who will listen about how very very good it is. I reviewed Katrina Porteous’s Rhizodont (Bloodaxe Books) for Poetry Salzberg Review fairly recently and posted an extended version of the review here. I concluded that ‘The people and landscapes of ‘Carboniferous’ are far more successful as poems to be read and enjoyed, while ‘Invisible Everywhere’ is a bold, well-intentioned experiment that fails’.

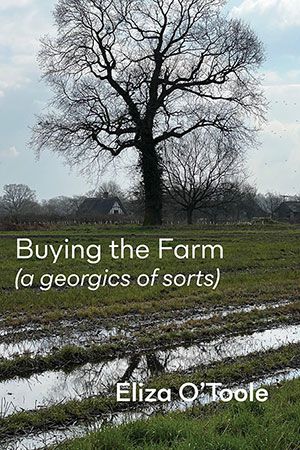

It is Eliza O’Toole’s A Cranic of Ordinaries (Shearsman Books) that I have been telling everybody about. Interestingly – and demonstrating the great enthusiasm the publisher shares for this poet – Shearsman have just published her NEXT collection: Buying the Farm (a georgics of sorts). The nominated collection was published in 2024.

I reviewed it in brief for The Times Literary Supplement recently, as follows:

The premise of Eliza O’Toole’s superb debut collection, A Cranic of Ordinaries, is unpromising: a year’s cycle of diaristic pieces in which the poet walks her dog through the Stour valley. But the result is a sublime form of ecopoetry which is visionary, yet creaturely and incarnate, and to achieve this O’Toole channels two great nineteenth century writers. Gerard Manley Hopkins’ ‘Hurrahing in Harvest’ joys in the things of Nature which are always ‘here and but the beholder / Wanting’. When self and natural world do communicate, Hopkins named that flash of true relationship ‘instress’. O’Toole’s ‘Stour Owls’ records just such a moment, listening to the calls of a female tawny owl, the ‘slight pin-thin / hoot’ of the male, followed by a tense silence: ‘then the low slow of the barn owl as the / white slide of her glide brushes the air we / both hold & then breathe’ (12).

O’Toole also adopts Emerson’s idea of the ‘transparent eyeball’, seeing all, yet being itself ‘nothing’. The excision of the self’s perspective is systematically pursued. Seldom is the landscape ‘seen’ but is rather subject to plain statement: ‘It was a machine-gun of a morning’ (11), ‘a vixen-piss of a morning’ (13), ‘a muck spread of a morning’ (34). O’Toole has an extraordinarily observant eye, but this repeated trope counters any taint of the constructed picturesque, the human-centring of vanishing points and perspective. The observer grows ‘part or parcel’ of the world. Such a vision makes demands on language because in truth, ‘It is necessary / to write what cannot be written’ (94), and this yields one of the most exciting aspects of this collection as the poet deploys varieties of plain-speaking, scientific, ancient, and esoteric vocabularies as well as a Hopkinsesque ‘unruly syntax’. She describes ‘young buds. Just starting from / the line of life, phloem sap climbing, / a shoot apical meristem and post / zygotic. It was bud-set’ (26).

O’Toole’s choices about form are also bold, almost all the poems being both right and left justified, creating blocks (windows?) opening on each page. The realm the reader is invited into (not told about, not shown) is one where the manifold particularities of the natural world are also and at once a whole. O’Toole’s dog digs a hole: ‘In / the hole and out of it, the soil was / whole. There was a unity and no lack. / In the hole was soil. It was a / comprehensive various entirety; it / was a universe of relatings’. (38) In such ways O’Toole’s ordinaries are made ‘strange’ (33) and the toxic divide between modern humanity and the natural is momentarily, repeatedly, bridged.

Here’s one of the poems from A Cranic of Ordinaries. Apologies are due for formatting accuracy as – as we all know – WordPress is rubbish at dealing with poetry. But you’ll get the idea…..

Perpetual gravity – Box Tombs at Wiston

(the quality of appearing to recede, essential to the landscape tradition)

Now illegible, the children of John

Whitmore and Susanna his wife,

Sarah aged 11 Months,

Robert aged 2 Years,

Rebeckah aged 11 Months,

Elizabeth aged …. Weeks,

Lucy aged 1 Week,

Susanna aged 20 Years,

Thomas Aged 6 Years.

John Whitmore departed this life Jany

the ….6th 1746 Aged (6)6. He was a

good husband loving father faithful

friend and a Good Christian. Susanna

Whitmore died / Jany. 25 1789 Aged

(?8)6. To dwell until all the world

inscribed when it was still possible to

die. To lie slightly foxed, mortared in

a brick box irregularly repaired, alive

with stone-devouring lichen and

littered with dry lime, leaves and

frass. Fin* pees antimony and sees off

the squirrel, wards off unbelievers we

have no need for having no place

amongst toppling tombs. A litany

indescribable, a conjugation beyond

reach, an accent mark over a vowel,

an entire landscape made grave. It

was October, the same fields were

ditched, furrowed, carved, still dug

over and still the Stour was flowing. In

the picture’s distant plain, the sun

like other yellows, was still fading.

Generally, a history remains unsure.

*O’Toole’s dog

The Laurel Prize awards £5,000 for the winner of the prize and £1,000 for the other four finalists – so congratulations are due to all of them. The winner will be announced at the Laurel Prize Ceremony which is taking place on Friday 19 September at 5.30pm (BST), and will be aired via a free live-stream. This year’s ceremony is a part of BBC Contains Strong Language which takes place in Bradford from 18-21 September.