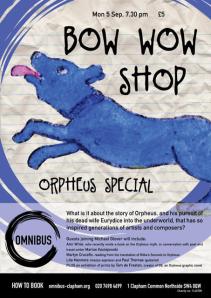

Last week I was pleased to be involved in the first of the on-line journal Bow-Wow Shop’s evening events in Clapham. Its focus was the figure of Orpheus: What is it about the story of Orpheus and his pursuit of his dead wife, Eurydice, into the underworld that has so inspired generations of artists, writers and composers?

Editor of The Bow-Wow Shop, poet and Independent arts and culture journalist, Michael Glover organises and he programmed a terrific mix of material. Ann Wroe’s 2011 book, Orpheus: the song of life (Cape), explores the roots of the Orphic story and traces its many manifestations through Classical to modern times. I was lucky enough to read with her at an event at Lauderdale House a couple of years ago. In Clapham she was in conversation with Marius Kociejowski. I was there on the strength of my 2012 translations of Rilke Sonnets to Orpheus (Enitharmon Press). Providing musical illustrations of the power of the Orpheus story were mezzo-soprano Lita Manners and guitarist Paul Thomas. There was also an exhibition of prints by Tom de Freston, creator of OE, a graphic novel on the Orpheus material.

Lita and Paul performed extracts for Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), songs by Vaughn-Williams and from the 1959 film Black Orpheus. Marius interviewed Ann though she needed little prompting to discuss several aspects of what is a wonderfully original book. Rilke’s inspired writing of the Sonnets to Orpheus (1922) form a thread through the book but she steered clear of that and concentrated more on the first evidence of the myth in the 6th BCE: a painting in black figure on a Greek vase, pictured with a huge lyre that almost seems part of him. Already at that early stage he is called ‘famous’. A 13th century BCE Cretan vase perhaps images him, again with the super-sized lyre (denoting divine powers, his music powerful even over inanimate objects birds, trees). Elsewhere he seems imaged as a bird himself – the power of song and music so strong that he must take on the attributes of a bird-god.

Perhaps even further back, Ann suggested, the figure is based on fertility myths, perhaps of Indian origin. His wife Eurydice likewise is linked to the figure of Persephone, the whole narrative in its original forms reflecting ideas of the seasons, death and re-birth of the earth, the crops. But there remains something irresolvable about the Orpheus myth – this polyvalent quality is one of the reasons for its productive quality in terms of inspiring artists. We kept recurring to the question: why must Orpheus turn as he is leading Eurydice out of the Underworld? The story contains its own tragedy. Ann suggested one interpretation might be to do with the fact the Eurydice represents the mystery of the natural world, or perhaps of knowledge/speech about the natural world, and that must necessarily remain hidden. Such a thing is the remit of the Gods alone. Orpheus must leave the Underworld empty-handed.

I spoke about Rilke in 1921, settling into the Château de Muzot in the Swiss Valais. How he liked to walk in the garden with its orchards and roses in full bloom, a landscape often evoked in the sonnet sequence which eventually arrived. He later declared that in the month of February 1922, he ‘could do nothing but submit, purely and obediently, to the dictation of [an] inner impulse’. In an extraordinary inspirational period, between the 2nd and 5th of that month, most of the 26 sonnets of Part One of Sonnets to Orpheus were written. He then polished off the ten year old sequence of the Duino Elegies. Between the 15th and the 23rd, Rilke went on to complete the 29 poems of Part Two.

Perrcy Bysshe Shelley wrote a longish fragment on the myth in 1820:

His [song]

Is clothed in sweetest sounds and varying words

Of poesy. Unlike all human works,

It never slackens, and through every change

Wisdom and beauty and the power divine

Of mighty poesy together dwell,

Mingling in sweet accord.

Here, as often, Orpheus is an image of the (male) artist/poet as well as being an image of our desire to find or create order or harmony in the world about us.

Rilke’s inspired poems brim with optimism and confidence about the role of poetry. In contrast, but more typical of the growing 20th century gloom, perhaps with intimations of a second world war, 15 years later – Auden’s brief 1937 poem ‘Orpheus’ is mired in uncertainty, asking “What does the song hope for?” Is it to be “bewildered and happy” – a sort of ecstatic but unthinking bliss? Or is it to discover “the knowledge of life”? No answer is given. The poem ends: “What will the wish, what will the dance do?” This is the Auden who doubts the power of poetry – it makes nothing happen – in his Elegy to Yeats.

And more like Auden than Rilke, the 20th century tended to take a more sceptical view of the myth – giving a more powerful voice to the traditionally passive Eurydice – more critical of Orpheus as careless, self-centred, weak. For example, in 1917 – 4 years before Rilke arrived in his chateau, H.D.’s Eurydice was condemning Orpheus:

for your arrogance

and your ruthlessness

I have lost the earth

and the flowers of the earth

Such radical revisions come also from more explicitly feminist poets like the American, Alta:

all the male poets write of orpheus

as if they look back & expect

to find me walking patiently

behind them, they claim I fell into hell

damn them, I say.

I stand in my own pain

& sing my own song

Carol Ann Duffy’s revision (in her 1999 book The World’s Wife) gives Eurydice both poem title and narrative perspective. Her Orpheus is:

the kind of a man

who follows her round

writing poems, hovers about

while she reads them,

calls her his Muse,

and once sulked for a night and a day

because she remarked on his weakness for abstract nouns.

She saves herself from having to accompany Orpheus back to the upper world by offering to listen to his poem again. Orpheus, seduced and flattered, turns. “I waved once and was gone” she comments.

In this context Rilke’s take on the myth is (not surprisingly) very traditional and brimming with confidence in the role of the poet and patriarchal sidelining of Eurydice. So Rilke’s interest lies with the world and the underworld, life and death. He is more like Shelley who set his fragmentary poem after the loss of E and it’s coming through that experience that seems to add power to his song. Rilke is interested in the idea of transition. Orpheus tries to recover Eurydice; he moves from life, into death and then back again. This fluidity, the courage and a readiness to renew ourselves, to be risked in the absorption with something other, to be translated from one realm to another, to come and go, to be and not to be is what draws Rilke to the myth.

This is also Don Paterson’s thinking behind his versions of the Sonnets in Orpheus (Faber, 2006). He argues Man is unique in having foreknowledge of his own death, meaning we act as if we are already dead, or historical. This means that we construct life as an authentic and intelligible narrative, a life with meaning, but it is death that drives the plot of our life. This is one of Paterson’s key ideas and he refers to it as our ‘ghost-hood’. So we are like Orpheus: we too have descended to the land of the shades and then returned to the present moment – our condition is therefore existentially transgressive, riven, divided.

It’s the singing of the Orphic artist that addresses and bridges such divisions. This explains Rilke’s interest in the Orpheus myth: its narrative is a metaphor for the longed-for transit or communion between the realms of life and death. He possesses the desired ability to inspire the renovation of human perception that can initiate a more comprehensive, joyful and celebratory experience of life. One of the things most people know of Rilke is his exhortation to praise. Praise is a form of secular prayer for Rilke and it demands a renovation of conventional language through Orpheus’ song – as also noted by Shelley in Prometheus Unbound:

Language is a perpetual Orphic song,

Which rules with Daedal harmony a throng

Of thoughts and forms, which else senseless and shapeless were

Orpheus’ singing as a way to think about the language of poetry can clearly be seen in Rilke’s celebratory sonnets about the garden at Muzot. Here’s my translation of sonnet I 13:

Pear and plump apple and gooseberry,

banana . . . all of these have something to say

of life and death to the tongue . . . I guess . . .

Read it in the expression on a child’s face

as she tastes them. It comes from far off.

Slowly, does speechlessness fill your mouth?

In place of words, a flood of discovery

from the flesh of fruit, astonished, free.

Try to express what it is we call ‘apple’.

This sweet one with its gathering intensity

rising so quietly – even as you taste it –

becomes transparent, wakeful, ready,

ambiguous, sunny, earthy, native.

O experience, touch, pleasure, prodigal!

Rilke’s vigorous and self-conscious mutations of the sonnet form create a variety of rhyme schemes, line lengths, iambic and dactylic pulses. David Constantine has described this as suitably fitting forms for the figure of Orpheus because he is himself a figure of transition, fluency and mystery.

Forthcoming Bow-Wow Shop events in Clapham will focus on the work of Edward Lear and Gabriel Garcia Lorca.