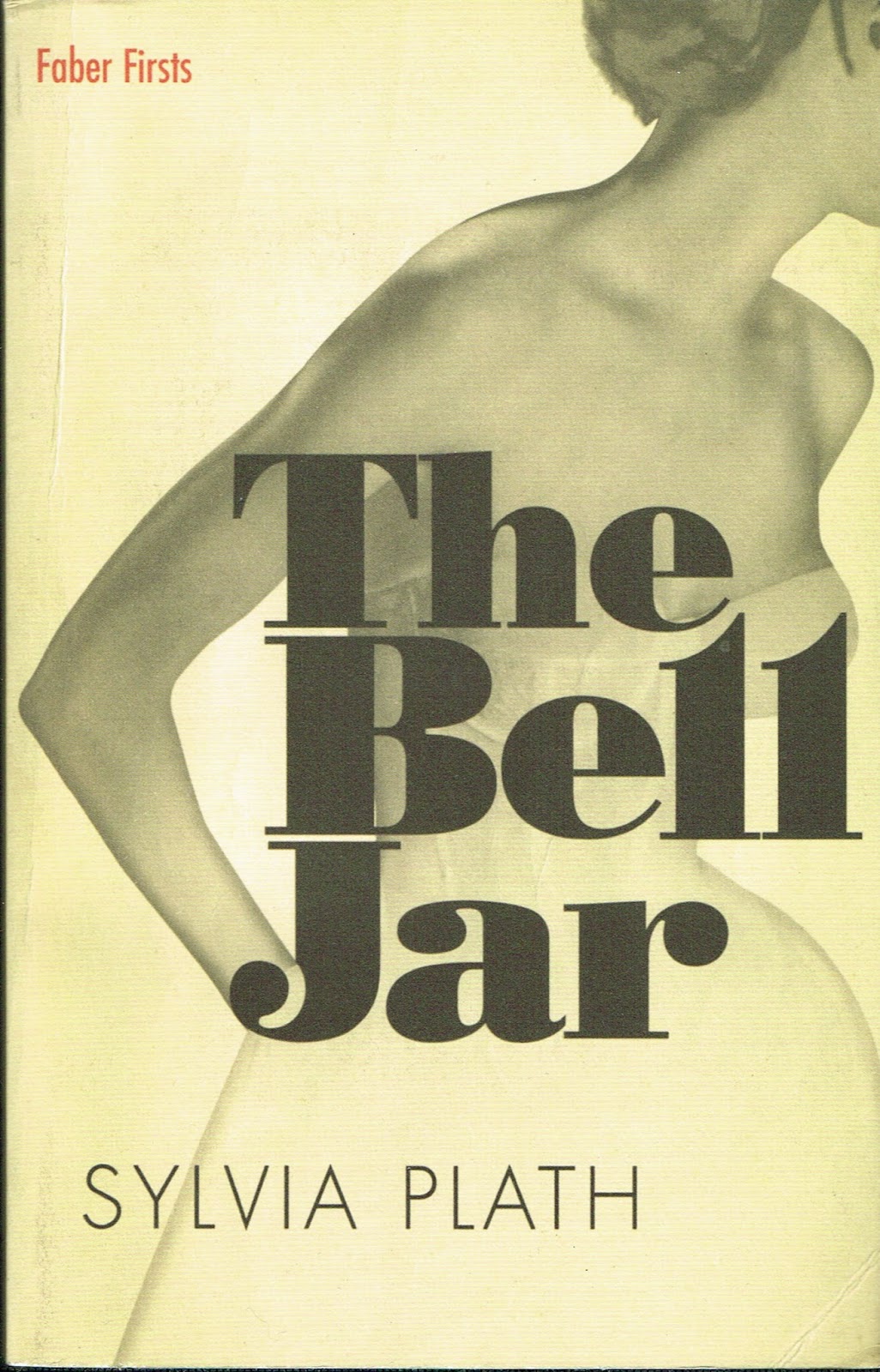

A couple of recent experiences with my own poems being posted/published on-line and kind readers then commenting on them has made me think again about the use of the first-person singular in poems – the use of ‘I’. Perhaps ‘think again’ is the wrong phrase as I have never – or at least not since my far distant teen years – really thought of the ‘I’ appearing in my poems as identical to the biographical, historical, personal ‘me’ tapping this out on a keyboard on a sunny Tuesday morning after the Easter weekend. How many millions of times have I suggested to students: let’s not make the assumption that the ‘I’ in Sylvia Plath’s poems is necessarily Sylvia Plath. And that perhaps is not the best example to give as we’ll then get into a debate about what exactly ‘confessional’ poetry is. But the fact that there has sprung up a category of ‘confessional’ suggest that the majority of other poems are not of that type. In which case the ‘I’ is to be taken with a large pinch of salt. Poems are not diaries or even journals but finely (I mean carefully) constructed mechanisms and the ‘I’ is but one of the building blocks.

Artists regularly move trees I’m told (within their frame). A painting is not a documentary. Some way back I remember reading that Auden would switch a positive to a negative for the sake of the music he aspired to. I’ve often found myself suggesting (in workshops) that the writer might try shifting the first person to the third, even the masculine pronoun to the feminine. These are just the little lies we tell in order to express the larger truth we are aspiring to and I’d fight to preserve that freedom of language and imagination, even the questions it might raise about ‘identity’. But what about the two poems I mentioned before. What was going on there?

The first poem appeared on Bill Herbert’s fascinating Ghost Furniture Catalogue site – which if you haven’t been there – go! Responses to this poem seemed to suggest the literalness with which some readers will approach a poem as voicing a ‘personal’ experience. Perhaps I was already wary of a too literal reading even in sending it out for publication. The title (‘A bedroom paranoia’) I chose wants to warn readers: there is something fantastical or imaginary here – there is a paranoia at work (that is not really the truth). One thing I’d say about the poem was that the experience – based on a real incident – had been sitting in a notebook for several years. I’d always felt there was something interesting in it – but couldn’t get it anywhere near right. I think my own learning experience was that to succeed you have to move a few trees… The opening 5 lines are (I’ll admit) close to the truth…

Pitch-dark, the carpet brushed by the door,

hush-ush, you’re up, a while, now you’re back,

damp from the shower, waking the radio,

and – who knew? – a king’s birthday, his anthem

x

limping on while you find clothes for the day

…. but by the time I felt I was getting close to the true poem that I wanted, the Queen had died and I had to substitute her son, Charles III, for her, in order not to make the whole thing misleadingly ‘historical’. The door brushing the carpet is something to be heard every morning. The woman rising before the (loafing) poetic voice is also not uncommon in real life. It’s the second line that is crucial: ‘hush-ush, you’re up, a while, now you’re back’. I wanted to evoke my own experience of dozing to and fro, time slipping forwards without being conscious (awake) to experience it. And that experience is taken up in the next 4 lines:

and I roll – the pomp now fading – to take

my usual plunge, all the way to the floor,

turning to smile at you. But the shadows

x

are vacant where you stood moments before

The first person has dozed off again for several minutes and the woman has simply gone downstairs to begin her day. The paranoia kicks in in the final 5 lines, despite the rational mind knowing what has happened. I wanted to capture (something I did feel to a degree) the sense of ‘what if’? What if the partner had gone not merely down the stairs but off into the world, away from home, never to return? I thought ‘brute stab of abandonment’ was a decent phrase for this emotional moment.

and – though explaining this is easy

as my drifting in and out of sleep – all day

x

I’ll nurse the brute stab of abandonment,

gone – the shock – you left no word – worse,

you were sure no word was worth the leaving.

Looking back, the verb ‘nurse’ seems important. The paranoia is largely self-inflicted, even encouraged (even as the day goes on), in a kind of picking at a scab, a masochistic inclination to ‘try out’ how that ‘abandonment’ would feel. I don’t think this is an admirable trait – but one which of us would say we have never felt? It’s here that the fictionalising comes in. I don’t think I DID feel like this all day, but I’m happy to represent ‘myself’ in this way to explore the (rather male?) emotional response. One of the comments on this poem was to commiserate with me that my partner had indeed actually left me. I guess that needs to be read as a compliment: it suggests the poem conveys the ‘stab’ as pretty convincingly ‘true’.

The second poem was recently published in Poetry Scotland and I trumpeted the fact (as you do) with a Facebook post to which there were a number of likes and comments. Several clearly implied that the reader had read the poem as autobiographical. In fact, there is less here that is personal than the previous poem. It derives from notes I made back in the time of Covid. My own father in fact died before the pandemic (a fact for which I often feel grateful… then guilty). So – as the poem discusses an absent father – the truth it is exploring is my own ‘feeling’ about an absent parent (though the cause of death is different). The title was a late addition (‘How to Address the Inquiry’), chosen as the Covid Inquiry has been taking place (to very little public response. The tone of the poem is angry:

If he was still in his armchairbeside me

I guess I’d try to raise a smile—

perhaps, for want of better, with this tale

of last night’s troubled tossing in bed

one arm snagging the bedside lamp

x

to bring it thump onto the bridge of my nose

to leave a bleb of dried blood

in the mirror this morning proving

I fought and lost—or else I might

tease him with his beloved City

x

in the fight for relegation again

or perhaps I’d pull back the curtain

you see there! a few primroses!

Plenty of the detail here is personal – the wrestling with the bedside lamp actually happened (to me – though after Dad had died), he supported (rather unenthusiastically, Bristol City), he loved his garden. The next detail is pure fiction but I felt the showing of the image to a man already dead would be a powerful one:

or I’d find my phone and maybe show

the newly done memorial bench

x

bearing his name by a tree in the park

And I wanted to let him speak for himself, to express his own anger. To me he is one of the many voiceless dead, resulting from Covid, especially those in care homes (both my parents ended in such a place and died there), those who could not be visited by relatives and friends due to contact restrictions:

and in the quiet I’d hear ashes stir

a murmuring of lips beyond cracked

and inaudible though I know the gist

that I was let down—they’re slow to act

x

letting people come they let people go

running it’ll be fine! up their fucking flagpole

then backhanding fat cat chums

with a hundred and fifty thousand lives

a fire sale fobbed me off with shit deals

x

even dangling one last Christmas before me

only to shove it—old ashy whisperer—

foldedinto yourself a dishcloth

on the drainer—a hiccupping cough

into your pillow—a last companion—

x

too old to ventilate . . .

We all read the stories of deaths of this sort. None of this is ‘true’ to my own experience (or my parents) but this is where the ‘larger’ truth surfaces, and this was my own way of trying to say something about it. The poem ends very emotionally (for me) because it returns again to autobiographical details. I DO have this picture on my mantlepiece (behind me as I type this out). I’m drawing on my own sense of loss, but I hope the dovetailing with what is fictional (for me) is effective enough. People wrote indicating their compassionating sense that I had indeed lost a parent during Covid and I want to again take this as a compliment to the technical success of the poem in its final state.

I’ve his wedding day

on my fireplace—you should come see

how young they are with what awkward pride

he stands in sunlight at the end of the war

in his mid-twenties in his air force uniform

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”.

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”. For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?

For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?

Another young female narrator deliberately stays at home while her parents (conventionally) go to church on Sundays. She’s a teenage rebel without a cause as “The truth is I’m not sure what I did / those mornings”. The poem is built from a list (one of Littlefair’s favourite forms) of what she did and did not do. Littlefair is almost always good with her figurative language and here the girl is variously an undone shoelace, an open rucksack, a blunt knife. The urge to non-conformity outruns her imagination as to how she might spend her growing independence and there is an interesting tension at the last as her parents return, “whole” having “sung their hallelujahs” while the young girl is till restlessly revising her choice of nail polish, as yet unable to find what she’s after.

Another young female narrator deliberately stays at home while her parents (conventionally) go to church on Sundays. She’s a teenage rebel without a cause as “The truth is I’m not sure what I did / those mornings”. The poem is built from a list (one of Littlefair’s favourite forms) of what she did and did not do. Littlefair is almost always good with her figurative language and here the girl is variously an undone shoelace, an open rucksack, a blunt knife. The urge to non-conformity outruns her imagination as to how she might spend her growing independence and there is an interesting tension at the last as her parents return, “whole” having “sung their hallelujahs” while the young girl is till restlessly revising her choice of nail polish, as yet unable to find what she’s after.

I think I find this with some other poems too, though it’s partly because Littlefair is admirably intent on presenting the working world, the world of labour, as routine in contrast to the allure of a more adventurous life. ‘Assignment brief’ presents itself as an old familiar’s introduction to a new girl’s routine office job; the lists and proffered options are funny but they slowly run out of steam. Likewise, the promisingly titled ‘Usually, I’m a different person at this party’ flags latterly. I’m imagining this as narrated by an older version of the girl who half fell in love with Tara Miller. Here, she shadow-boxes the risks of conventionality by over-insisting on her own sweeping and glamorous life, in the process claiming all sorts of ‘interesting’ aspects of herself: “I only ever have large and sweeping illnesses. / My lymph nodes swell glamorously. I never snuffle”. But the contrasts here are again rather roughly hewn and, in the end, close to cartoonish.

I think I find this with some other poems too, though it’s partly because Littlefair is admirably intent on presenting the working world, the world of labour, as routine in contrast to the allure of a more adventurous life. ‘Assignment brief’ presents itself as an old familiar’s introduction to a new girl’s routine office job; the lists and proffered options are funny but they slowly run out of steam. Likewise, the promisingly titled ‘Usually, I’m a different person at this party’ flags latterly. I’m imagining this as narrated by an older version of the girl who half fell in love with Tara Miller. Here, she shadow-boxes the risks of conventionality by over-insisting on her own sweeping and glamorous life, in the process claiming all sorts of ‘interesting’ aspects of herself: “I only ever have large and sweeping illnesses. / My lymph nodes swell glamorously. I never snuffle”. But the contrasts here are again rather roughly hewn and, in the end, close to cartoonish. The latter view is more than a possibility given that Littlefair’s poems also boldly explore the self’s relation with itself. The encounter between self and future self is plainly and humorously told in ‘Visitations from future self’ and it finds the present self in trouble, pleading “I can’t go on / like this, my life a tap that won’t / switch on”. Here, the present self’s cliched and optimistic hopes for a “rain-before-the-rainbow thing” are denigrated and stared down by the future self. ‘Sertraline’ echoes Plath’s The Bell Jar in its evocation of a summer spent on an anti-depressive drug. And ‘Giraffe’ itself is a prose poem (there are 3 prose pieces in the whole book) in which a voice is offering reassurances to someone hoping to “feel better”. In a final list, images of a return to ‘health’ are offered. Particularly good is the idea that suffering will remain a fact but “your sadness will be graspable, roadworthy, have handlebars”. And lastly, “When you feel better, you will not always be happy, but when happiness does come, it will be long-legged, sun-dappled: a giraffe.”

The latter view is more than a possibility given that Littlefair’s poems also boldly explore the self’s relation with itself. The encounter between self and future self is plainly and humorously told in ‘Visitations from future self’ and it finds the present self in trouble, pleading “I can’t go on / like this, my life a tap that won’t / switch on”. Here, the present self’s cliched and optimistic hopes for a “rain-before-the-rainbow thing” are denigrated and stared down by the future self. ‘Sertraline’ echoes Plath’s The Bell Jar in its evocation of a summer spent on an anti-depressive drug. And ‘Giraffe’ itself is a prose poem (there are 3 prose pieces in the whole book) in which a voice is offering reassurances to someone hoping to “feel better”. In a final list, images of a return to ‘health’ are offered. Particularly good is the idea that suffering will remain a fact but “your sadness will be graspable, roadworthy, have handlebars”. And lastly, “When you feel better, you will not always be happy, but when happiness does come, it will be long-legged, sun-dappled: a giraffe.” The designation ‘a young poet to watch’ is over-used but on this occasion it needs to be said loudly. Giraffe contains a number of fresh, intriguing and fully-achieved poems. It’s well worth seeking out. I well remember reading and being very impressed by Liz Berry’s 2010 Tall Lighthouse debut chapbook, the patron saint of schoolgirls, and this selection from Bryony Littlefair’s early work runs it close. My review of Liz Berry’s subsequent, prize-winning full collection,

The designation ‘a young poet to watch’ is over-used but on this occasion it needs to be said loudly. Giraffe contains a number of fresh, intriguing and fully-achieved poems. It’s well worth seeking out. I well remember reading and being very impressed by Liz Berry’s 2010 Tall Lighthouse debut chapbook, the patron saint of schoolgirls, and this selection from Bryony Littlefair’s early work runs it close. My review of Liz Berry’s subsequent, prize-winning full collection,