‘I always write that which is not’ says one of Alireza Abiz’s poems, because ‘[t]hat which is is too terrifying / to wear the garment of the word’. To understand what Abiz means here – how can / why should a poet avoid writing of what is real? – we have to understand his historical and political contexts.

Abiz belongs to the 1990s generation of Iranian writers. The unattributed Introduction to The Kindly Interrogator (Shearsman Books, 2021) provides help for those of us who don’t know much about the development of modern Iranian poetry. It was Nima Yushij who, at the opening of the twentieth century, felt the then-current forms of Persian poetry had become too abstract, subjective and metaphysical. He advocated a more modern, objective approach, a more natural diction and the use of forms closer to what we would regard as blank verse. By the 1960s such freshness and freedom had yielded some of the best modern Persian poets, writing diversely, mostly in free verse. But both before and after the 1979 Revolution (which replaced a millennia old monarchical system with the Islamic Republic), poets continued to engage in political struggles and were often prosecuted by the authorities for their writings. Following 1979, and during the 8 years of war with Iraq, the artistic atmosphere continued to be both difficult and repressive.

The political reforms of the 1990s – Abiz’s period – saw a new optimism and revival in the arts, yet still prosecution and censorship remained a fact of life. Many artists left Iran and – especially after the 2009 uprising – there was a considerable migration into exile. Though currently resident in the UK (he lives in London and has a Creative Writing doctorate from Newcastle University) Abiz does not consider himself an exile as such, though inevitably his perspective has an ex patria quality, looking both dispassionately at Iran’s nature and continuing development, as well as harking back to an affective homeland.

In these translations by the author and WN Herbert, Abiz’s free verse poems are not always reluctant to address realities, but they do tend to deploy (what the Introduction calls) a kind of ‘dialled-down or even buttoned up surrealism’. ‘The Tired Soldier’ is brief and universal. His weariness is symptomatic of a lengthy war, as well as his disillusionment with it. Jackals wail, bugles “cough” like roosters – the real and figurative creatures here close to anthropomorphic portraits of societal/political elements, close to the derangement of the surreal which is also signaled in the soldier’s action which (besides the obvious disrespect for his military service) involves an overturning, a literal inversion (feet to head, head to feet) of the norm:

The tired soldier

hangs his boots around his neck

and pisses in his helmet.

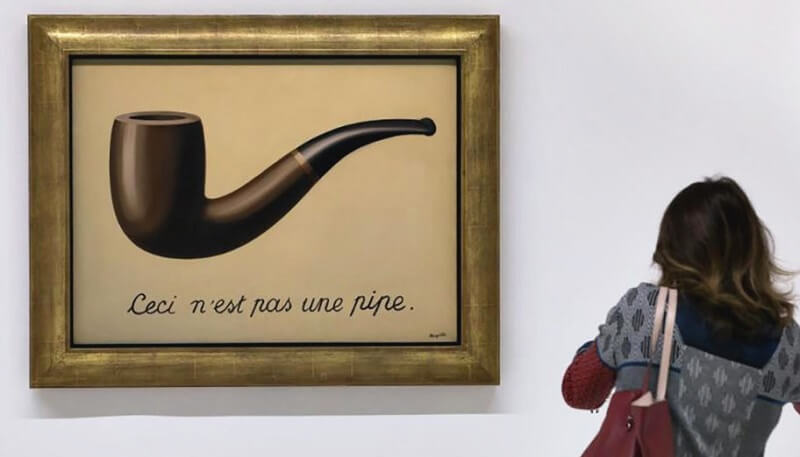

The surreal is inevitably emergent when we cease to trust our senses, or our interpretation of what we think we witness (think of Rene Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe). A black cat watches the narrator from the veranda. Given a political context in which persecution (even elimination) has become common currency, the narrator seems to fear for his own life:

It’s been a long time since I was a sparrow,

since I was a dove,

even since I was a backyard hen.

The sense of danger and paranoia here is obvious, but perhaps vague enough, quirkily surreal enough, to elude the censors. The Introduction suggests parallels with the Menglong Shi or so-called ‘Misty Poetry’ generation of writers in China in the 1980s. Then, the ‘Misty’ handle was initially a disparaging one given by officially sanctioned reviewers, suggesting these writers were creating ‘obscure, vague, incomprehensible work’ (for a good account of these issues see Yang Lian’s introductory essay to Jade Ladder: Contemporary Chinese Poetry (Bloodaxe, 2012) edited by WN Herbert and Yang Lian). But their obscurity was only really in comparison to official Chinese poetry of the period full of banal (but never obscure) sloganizing about the virtues of Socialism and the evils of Capitalism. Yang argues the mistiness of the new 1980s Chinese poets was really a return to ‘Sun, Moon, Earth, River, Life, Death, Dream’ – to the territory of Classical Chinese poetry (Li Bai and Du Fu), though often encoded within it were observations about contemporary political life. So also with Abiz’s poetry in which images of ‘doves, rabbits, ghouls, lemons, feasting, wine’ develop and imply their own slant or misty significances.

Inevitably, death and the threat of it is a preoccupation of many of these poems. The mundane incident of a fly buzzing in a kitchen leads to a meditation on conflict, guilt and futility. Looking through a window into ‘The Anatomy Hall’, the narrator sees a surgeon? a mortician? a torturer? leaning over a body on a table. He senses the man’s fear; he glimpses the flash of a knife. Then:

He bends over my head and smiles,

looking at me like a butcher looks at a carcass.

X

On the table in the middle of the hall,

relaxed, I sleep.

The relaxation of the victim comes as an additional surprise, but it gestures towards the sense of complicity that is another of Abiz’s concerns. A lengthy quotation in the Introduction, which I take to be in Abiz’s own words, argues: ‘the corrupting influence of dogmas is so insidious that no-one remains entirely innocent, or, if carried along by the paranoias of ideological purity, should be considered completely guilty’.

So in ‘The Informer’ the narrator (in a Kafkaesque sort of world) has been invited to attend a ceremony to select the ‘finest informer’. There appears to be a confident pride in the way he dresses up for the occasion. In the hall, the candidates (those you expect to be on the ‘inside’) are in fact excluded. It turns out, in a detail suggestive of the elusive nature of truth and the levels on levels of surveillance in such a repressive society, that all the seats are to be taken ‘by the officers responsible for informing on the ceremony’. There is a calculated bewilderment to all this as is also revealed in the oxymoronic title of the eponymous poem, ‘The Kindly Interrogator’. Nothing so simple as a caricatured ‘bad cop’ here:

He’s interested in philosophy and free verse.

He admires Churchill and drinks green tea.

He is delicate and bespectacled.

He employs no violence, demands no confession, simply urging the narrator to ‘write the truth’. The narrator’s reply to this epitomises the uncertainties a whole society may come to labour under. He cries, ‘on my life!’. Is this the ‘I will obey’ of capitulation or the ‘kill me first’ of continued resistance? Is this the repressed and persecuted ‘life’ of what is, of what is the case, or an expression of the inalienable freedom of the inner ‘life’? Abiz is very good at exploring such complex moral quandaries and boldly warns those of us, proud and self-satisfied in our liberal democracies, not to imagine ourselves ‘immune from [the] temptation towards unequivocality’. Fenced round with doubt, with a recognition of the need for continual watchfulness, with a suspicion of the surface of things, perhaps these poems never really take off into the kind of liberated insightfulness or expression of freedom gained that the Introduction suggests a reader might find here. Abiz – the ‘melancholic scribbler of these lines’ – is the voice of a haunted and anxious conscience, a thorn in the side of repressive authorities, as much as a monitory voice for those of us easily tempted to take our eye off the ball of moral and political life nearer home.

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

Akbar doesn’t generally do the more familiar, simply focused poem. There are a few in the book like ‘Learning to Pray’, in scattered unrhymed triplets, in which a young boy (Akbar allows a straight autobiographical reading usually) watches his father pray, “kneeling on a janamaz” or prayer mat. The wish to emulate the admired father is conveyed pin-sharp. A later poem also starts from childhood and (mostly in loose unrhymed couplets) traces the boy’s later maturing in an America “filled with wooden churches / in which I have never been baptized” (‘Personal Inventory: Fearless (Temporis Fila)’). This poem also attracts threads of two of Akbar’s other main themes: his personal addictions and the ubiquitous sense of living in a fallen world.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

One of the main elements of this fallen state (again Akbar allows a simple autobiographical interpretation) is the damage caused by his past addictions, especially to alcohol. This is the main hook Penguin hang the book on (a cover of empty beer bottles, for example). Poems styled ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic …’ recur throughout the book, but the first section is most focused on this. A familiar comment from W.H. Auden is used to firmly yoke spirit to bottle: “All sins tend to be addictive, and the terminal point of addiction is damnation”. Many of the poems then have this sense of inebriation, muddling, confusion which Akbar’s style of writing is very at home with. ‘Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and Housefly’ presents the drinker waking up, seemingly attacked by a home invader with a knife. Memories of keeping a housefly on a string intervene, perhaps because in the fly’s death the young boy confronted the idea of death: “I opened myself to death, the way a fallen tree // opens itself to the wild”. The poem returns to the threatening situation, then to more abstract thoughts of scale, a TV programme and the speaker passively returns to sleep. This is a great poem of the self as both endangered and paranoid, distanced from danger, the blurring of perception, thought and memory.

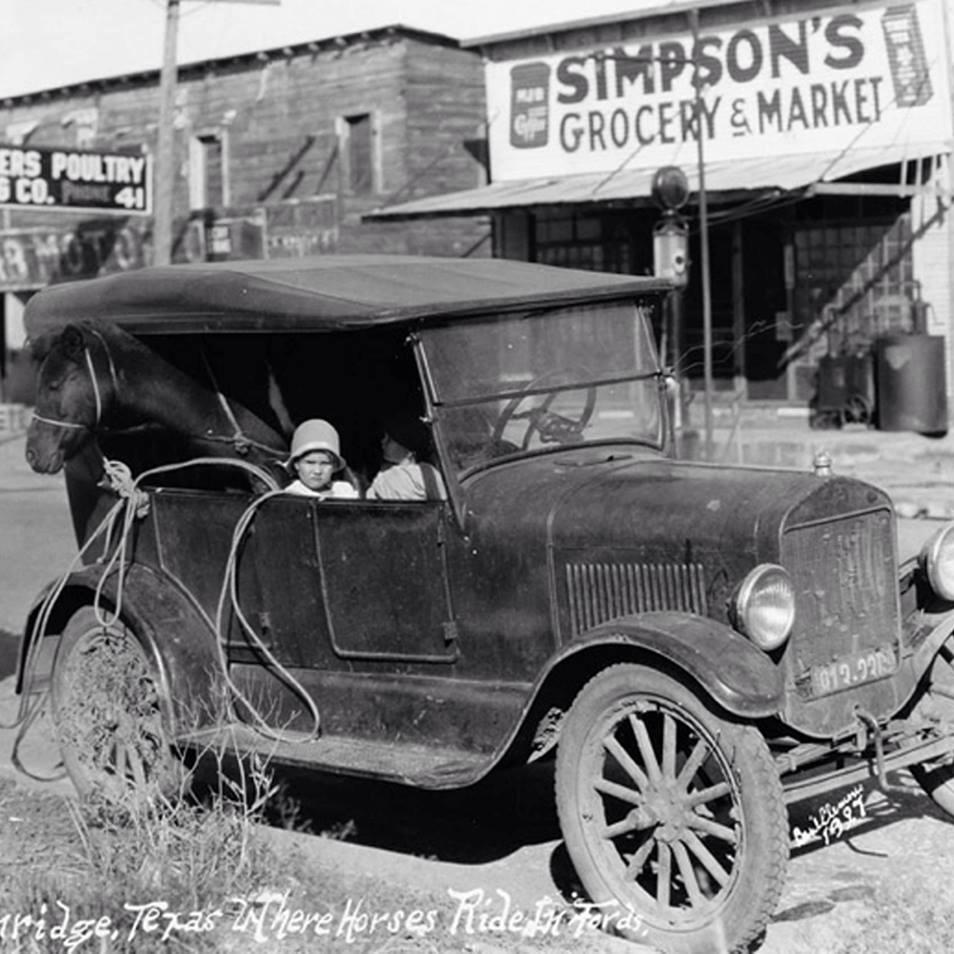

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.

But when it works, these are marvellous poems – and, for my money, this book would make a worthy winner of the 2018 Felix Dennis Prize. ‘Wild Pear Tree’ – as if in one breath – conveys a wintry scene/mental state, recalls halcyon days (of spring) and ends lamenting the forgetting of an “easy prayer” intended for emergencies: “something something I was not / born here I was not born here I was not”. ‘Exciting the Canvas’ is much more risky in its jig-sawing together of disparate elements – a bit of Rumi, the sea, a child’s drawing, a drunken accident, the Model T Ford, crickets, snakes – but somehow manages to hold it all together to make a snap-shot of a troubled, curious, still-open consciousness. And finally, ‘So Often the Body Becomes a Distraction’, dallies with the Rilkean idea of dying young, alludes to recovery from addiction, then grasshoppers, ice-cubes, personal ambitions and the self-image of “rosejuice and wonderdrunk” (which is merely one side of Akbar’s work). This one ends with the not-infrequent trope of a re-birth from burial in the earth. I like these images, suggesting that, for all the fretting about lost paradise, the absence of God, the self-destructiveness of the individual, whatever redemptive re-birth may be possible is only likely to come from our closeness and attentiveness to things about us, an eschewing of the “self-love” Akbar struggles to free himself from in ‘Prayer’: in a lovely phrase –though I’m still figuring it – he concludes, “it is not God but the flower behind God I treasure”.