(Thanks to Bloodaxe Books for a review copy of this collection)

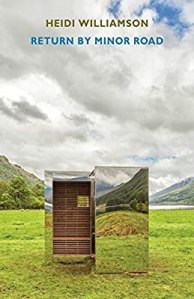

The return alluded to in Heidi Williamson’s Return by Minor Road (Bloodaxe Books, 2020) is partly physical, but predominantly one of memory and yet, the book argues, it is an almost redundant journey in that we carry important events with us anyway. In confronting a particular tragic event from the past, these poems strike me as offering routes through our current experiences – of pandemic, grief, lockdown – in particular an appreciation of the ‘minor roads’ along which we might recover a sense and shapeliness in what now strikes us as chaotic and closer to a deletion of meaning.

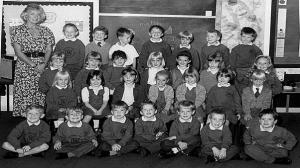

The event at the centre of this collection occurred at Dunblane Primary School, north of Stirling, Scotland, on 13 March 1996, when Thomas Hamilton shot 16 children and one teacher dead, injuring 15 others, before killing himself. It remains the deadliest mass shooting in British history. What Williamson is not doing here is exploring the nature of evil, the damaged personality of the perpetrator, or the wider political/social fallout of such terrible events. She was living in the area at the time (I think as a student) and this retrospective collection is divided into three parts: the haunting of memories (but Williamson has more powerful ways of articulating this than the ‘ghostly’ metaphor), the re-examining of the actual event, and a physical re-visiting of the location.

The event at the centre of this collection occurred at Dunblane Primary School, north of Stirling, Scotland, on 13 March 1996, when Thomas Hamilton shot 16 children and one teacher dead, injuring 15 others, before killing himself. It remains the deadliest mass shooting in British history. What Williamson is not doing here is exploring the nature of evil, the damaged personality of the perpetrator, or the wider political/social fallout of such terrible events. She was living in the area at the time (I think as a student) and this retrospective collection is divided into three parts: the haunting of memories (but Williamson has more powerful ways of articulating this than the ‘ghostly’ metaphor), the re-examining of the actual event, and a physical re-visiting of the location.

The personal nature of the response offered by these poems is flagged in an epigraph from Jane Hirshfield: “our fleeting lives do not simply ‘happen’ and vanish – they take place”. She means that events do not slip away into the past, but take or carve out a place in our historical and present selves and it is this geographical/topographical idea that Williamson pursues so effectively in many of the poems. The particular, the creaturely and the personal predominate. A mother settles her child back to sleep at night – the troubled sleep patterns of the innocent in this context have immediate resonance – and returning to her own bed she finds how awkwardly the bedspread rucks up, “how hard it is to settle”. Uneasiness at night recurs in ‘Thrawn’, images of Allan Water (the river running through Dunblane) surfacing years after the event. ‘Loch Occasional’ again uses a local geographical reference to suggest the sudden flooding of memories, when “the silt of what happened rises” and – echoing Hirshfield’s comment – the “occasional”, which one might expect to have its moment and vanish, is said to “endure”. The rise and fall of Allan Water is the primary image for the persistence of memory in so many of these poems. Rain falling, “insistently / with its own unnameable scent”, is an image chosen elsewhere and (rather more conventionally, à la Henry James) ‘Fugitive dust’ is literally haunted by the figure of a child.

What such resurfacings mean in personal, day-to-day terms is clear in the prose poem, ‘It’s twenty-two years ago and it’s today’. Besides the form, this is a different style of writing: shorthand, a journalese of plain statement, brief jottings of a day spent with husband and child. The ordinary is tilted out of true by unwanted remembrance, manifesting as unusual quietude, the papers left unread, the phone disconnected: “Neither of us says why”. Halfway through this poem, the narrator manages to write, she says, “[s]mall hard coughs on the page”. Perhaps this alludes to the (again) quite different style of verse in ‘Cold Spring #1’ which is the key section recounting the events of the 13 March 1996, though the massacre itself is reduced to a single word, “incident”. Covering 4 pages in total, we are given dislocated fragments only – speech, visual images – as an ordinary day turns into an historical event. This works really well and, without pause, the poems move off again to explore the aftermath: phone calls from worried relatives and friends, hesitant visits to the local pub, encounters with news journalists, memorial flowers already beginning to fade.

What the book offers as healing counterweight to the massacre – and there’s no doubt that Williamson wants to offer something despite the troubled days and nights, despite quoting from Hopkins’ ‘terrible sonnet’, ‘No worst there is none, pitched past pitch of grief’, despite allusions to the “uncontrollable heart” – what the poems offer is the natural world’s existence and persistence and the innocence of the child. Williamson’s response to nature is always powerful and detailed, carrying a lode of emotional implications. As has become a commonplace idea in these ‘lockdown’ times, the loss or expansion of our narrow selves in the world of nature is redemptive. ‘Dumyat’ opens:

Some days we cried ourselves out,

packed our coats and climbed

the soggy rock to its small summit.

There was something about stepping

one by one, beside each other

without speaking, without the need.

Elsewhere, striding up into the nearby Ochil Hills was a way to “clear us of ourselves”. Another poem celebrates the “Reliability of rain. / Durability of rain” and in another the (relative) unchanging nature of the nearby Trossachs offers a consolation of sorts; I guess a longer perspective in which even such human-scale horrors must be found to shrink.

It is also the presence of – and the need to provide for and protect – her own child that offers a path beyond tragedy. The title poem offers a straightforward account of Williamson’s return to the landscape of Dunblane, but she and her husband visit with their child who carries nothing of what the place means to his parents, hence he is innocent, complaining, distracted, playful … The poem ends with the child playing a horse racing game, taken down from the hotel bookshelf, in a wonderful image of the onward propulsion of youthfulness, its greed for the future, the as-yet unburdened nature of its vitality: “He gallops his horses forwards, forwards”.

I don’t mean to give the impression that Williamson’s book offers anything like an ‘easy’ response to the horrors of Dunblane. The ‘minor roads’ by which people mostly manage to pick up their old lives – here nature and family – remain shadowed and troubled in two late poems. ‘Self’ offers a liturgical series of questions to which the poet can only ever answer “I don’t know” and the concluding poem also makes use of repetition, recording the landscapes around Dunblane once again with the repeats playing variations on the idea that all this was left behind when the poet moved away and yet all this was also carried away too. It’s the paradox of the book as expressed to perfection in the poem ‘Culvert’. More typically in this poem, Williamson observes her “unassuming heart” and the water images recur with the heart becoming a valley collecting waters and debris after a downfall (the traumatising event). But the event does not merely pass through the heart:

I don’t mean to give the impression that Williamson’s book offers anything like an ‘easy’ response to the horrors of Dunblane. The ‘minor roads’ by which people mostly manage to pick up their old lives – here nature and family – remain shadowed and troubled in two late poems. ‘Self’ offers a liturgical series of questions to which the poet can only ever answer “I don’t know” and the concluding poem also makes use of repetition, recording the landscapes around Dunblane once again with the repeats playing variations on the idea that all this was left behind when the poet moved away and yet all this was also carried away too. It’s the paradox of the book as expressed to perfection in the poem ‘Culvert’. More typically in this poem, Williamson observes her “unassuming heart” and the water images recur with the heart becoming a valley collecting waters and debris after a downfall (the traumatising event). But the event does not merely pass through the heart:

it was the heart,

rent in the same way

a clearing is made

by great and incremental

incidents.

Experiences make the heart what it is, carving our selves, finding a permanent place within them, shaping them for the future, always flowing through them, even if unseen for the most part:

its pulse ebbs in culverts

below neat estates,

a furtive love trickling

deeper and deeper.

Love of the natural world and love of family – especially youth – resonates through this quietly convincing collection which manages to take on its daunting subject matter and emerge, not victorious of course, but having argued on behalf of resilience, on the side of hope.

Love of the natural world and love of family – especially youth – resonates through this quietly convincing collection which manages to take on its daunting subject matter and emerge, not victorious of course, but having argued on behalf of resilience, on the side of hope.

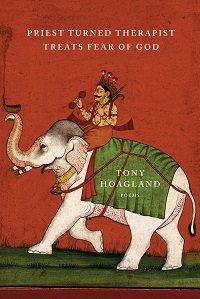

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).

Nevertheless, some uncertain light can be cast on the human condition by ‘The Neglected Art of Description’. A man descending into a man-hole can remind us of “the world // right underneath this one” though Hoagland treats this idea with three doses of ironic distancing. He’s even more confident that the pleasures of perceptual surprise can “help me on my way” (even this, an equivocal sort of progress and destination; no golden goal).

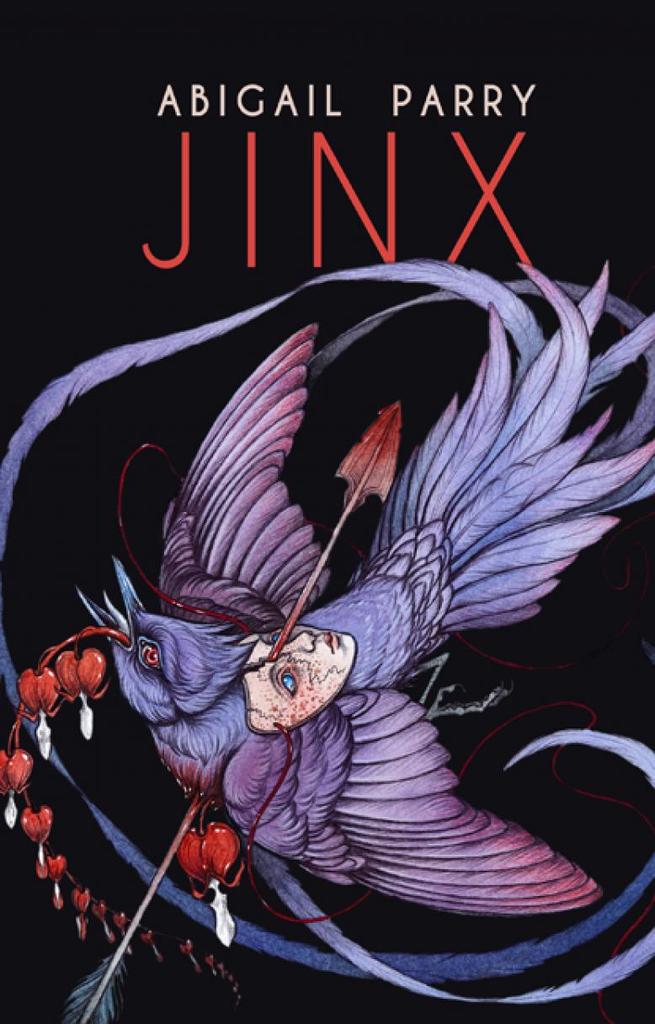

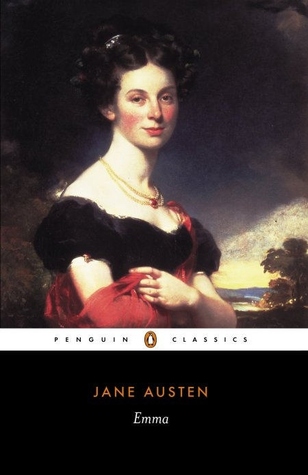

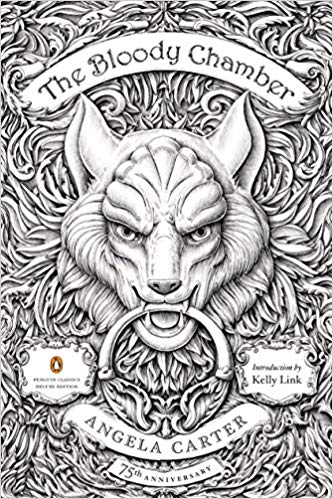

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”.

Mr Knightley is an absent figure in that poem, but Jinx is repeatedly visited by powerful, seductive, dangerous males who – in ways now very familiar since Angela Carter started the ball rolling – are morphed into animal figures. ‘Hare’ is an early example, leaning invasively over the female narrator at a wedding party, “those fine ears folded smooth down his back, / complacent. Smug. Buck-sure”. As in ‘Daddy’, the woman is drawn to the man despite (or because of) his obvious threat but unlike Plath’s powerful final repulse (“Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through”), Parry’s narrator is fatalistic: “Your part is fixed: // a virgin going down, / a widow coming back”. Elsewhere, ‘Goat’ and ‘Magpie as gambler’ work similarly and ‘Ravens’ is a particularly Plathian version: “In fact, every man I thought was you / had a bird at his back / and a black one too”. For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?

For all the frenetic playfulness of the book, Parry’s mostly female narrators and subjects are beset by threats. ‘The Lemures’ re-Romanises the creatures into psychological pests, aspects of self-doubt perhaps, appearing on the furniture, at the roadside, in a reflection in a lift door: “They will steal from you. Pickpockets, / rifling the snug pouches at the back of your mind”. Parry is evidently a fan of mid-twentieth century film and she explores Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man from the perspective of dark powers surfacing. The question being asked is whether such forces represent the overturning of the real self or the manifestation of it in contrast to what a later poem calls “the dreary boxstep of propriety”. Locks and keys recur in the poems – are we confined, or about to set something loose, or to leap to real freedom?

It may be that this ability to be sustained by scraps and glimpses, the sense that the self is most fully resolved in a lack of egotism, in its encounter with ordinary things, can diminish some of the sting of mortality. In a poem like ‘White’, MacRae manages to celebrate again the ordinariness of familiar things while at the same time sustaining a contentedness (or at least an absence of fear) at the prospect of the self’s vanishing: “You can disappear in a house where / you feel at home; the rooms are spaces / for day-dreams, maps of an interior / turned inside out”. Rather than Macbeth, it is Hamlet’s resolve to “let be” that comes to mind as this calm, accessible, colourful and wonderfully dignified poem concludes:

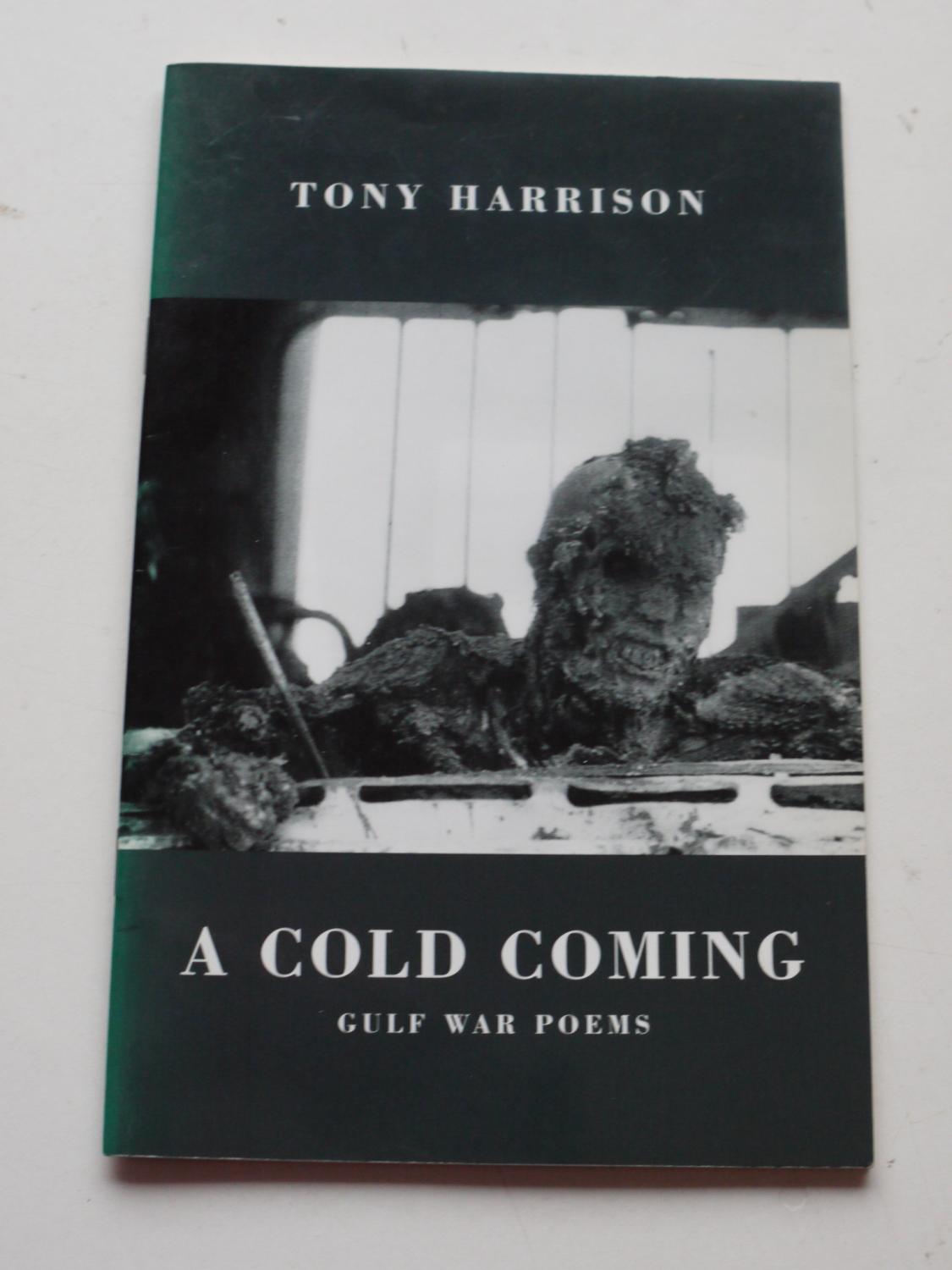

It may be that this ability to be sustained by scraps and glimpses, the sense that the self is most fully resolved in a lack of egotism, in its encounter with ordinary things, can diminish some of the sting of mortality. In a poem like ‘White’, MacRae manages to celebrate again the ordinariness of familiar things while at the same time sustaining a contentedness (or at least an absence of fear) at the prospect of the self’s vanishing: “You can disappear in a house where / you feel at home; the rooms are spaces / for day-dreams, maps of an interior / turned inside out”. Rather than Macbeth, it is Hamlet’s resolve to “let be” that comes to mind as this calm, accessible, colourful and wonderfully dignified poem concludes: For MacRae’s interest in and skill with poetic form, we need look no further than the extraordinary glose on a quatrain from Alice Oswald (the earlier collection contained another on lines from Mary Oliver). For most poets, this form is little more than an exhibitionist high-wire act, but MacRae’s poems are moving and complete. Her use of poetic form here, particularly in some of these last poems, reminds me of Tony Harrison’s conviction that its containment “is like a life-support system. It means I feel I can go closer to the fire, deeper into the darkness . . . I know I have this rhythm to carry me to the other side” (Tony Harrison: Critical Anthology, ed. Astley, Bloodaxe Books, 1991, p.43). Appropriately, in ‘Jar’, she contemplates with admiration an object that has “gone through fire, / risen from ashes and bone-shards / to float, nameless, into our air”. Here, the narrator movingly lays aside the wary scepticism of the Thomas epigraph and rests her cheek on the jar’s warmth to “feel its gravity-pull / as if it proved the afterlife of things”.

For MacRae’s interest in and skill with poetic form, we need look no further than the extraordinary glose on a quatrain from Alice Oswald (the earlier collection contained another on lines from Mary Oliver). For most poets, this form is little more than an exhibitionist high-wire act, but MacRae’s poems are moving and complete. Her use of poetic form here, particularly in some of these last poems, reminds me of Tony Harrison’s conviction that its containment “is like a life-support system. It means I feel I can go closer to the fire, deeper into the darkness . . . I know I have this rhythm to carry me to the other side” (Tony Harrison: Critical Anthology, ed. Astley, Bloodaxe Books, 1991, p.43). Appropriately, in ‘Jar’, she contemplates with admiration an object that has “gone through fire, / risen from ashes and bone-shards / to float, nameless, into our air”. Here, the narrator movingly lays aside the wary scepticism of the Thomas epigraph and rests her cheek on the jar’s warmth to “feel its gravity-pull / as if it proved the afterlife of things”.![p045rwch[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/p045rwch1.jpg)

![train[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/train1.jpg)

![DuncanForbes-200x245[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/duncanforbes-200x2451.jpg)

![blogcharlescausley2[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/blogcharlescausley21.jpg)

![wp2f72b580_06[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/wp2f72b580_061.png)