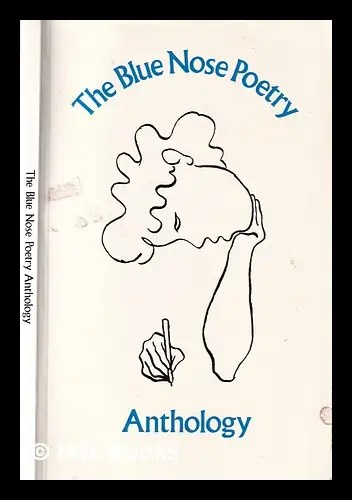

I recently attended the launch of Philip Gross’ new collection, The Shores of Vaikus (Bloodaxe Books, 2024) at the Estonian Embassy (the poems and prose pieces in the book refer to Gross’ father’s Estonian heritage and the poet’s visits to that country). I’ve followed his poetry since Faber published The Ice Factory in 1984. Neither of us could recall when we’d last met up but, after the event, I remembered that Philip was one of the first poets to read at the series of poetry readings (and associated workshops) I helped curate in the late 1980s/early 1990s, the Blue Nose Poetry series in London. I introduced him on the occasion (I still have the notes I made for the event in a Notebook for Spring 1989). I checked out the precise date in The Blue Nose Poetry Anthology (1993) which has sat on my shelves for many years now. The Blue Nose Poets (for personnel see below) invited all those who had read in the series to submit work and it strikes me now that it would be a shame if a record of our endeavours over a number of years was lost to sight completely. So, I’m posting here the Introduction to the Anthology and the full list of readers who appeared (often being paid nothing or a mere pittance) between 1989 and 1993. Interesting? I think so – given we hosted the likes of Dannie Abse, Patience Agbabi, Moniza Alvi, Simon Armitage, James Berry, Robert Creeley, Fred D’Aguiar, Michael Donaghy, Carol Ann Duffy, Michael Horowitz, Jackie Kay, Adrian Mitchell, Peter Porter, Peter Reading, Michèle Roberts, Ken Smith, and many more.

Introduction to The Blue Nose Poetry Anthology

This anthology celebrates four years of Blue Nose Poetry in London. Its beginnings can be traced back to 1988, when Sue Hubbard advertised for members to join a small poetry workshop at her house in Highbury. Amongst others who began meeting regularly were the four founder members of the Blue Nose: Sue, Martyn Crucefix, Mick Kinshott and Denis Timm. At that time, poetry readings in London seemed to be in the doldrums. Uninviting rooms and draughty halls with chairs in impersonal ranks were often depressingly matched by poor organisation. The Blue Nose Poetry activities were set up with the express intention of providing workshops and readings in a friendly, accessible and organised atmosphere for new voices, up and coming writers and the already established. We were convinced that a cabaret setting of tables, candles and a drink with other enthusiasts could make poetry enjoyable. It was only with the discovery of The Blue Nose Cafe in Mountgrove Road, close to Highbury Stadium, that we found a name for the project and the real success of the Blue Nose began.

Our first poets came to the Cafe and read out of the goodness of their hearts. We thank them all once again. The first event with Michèle Roberts was packed and exceeded our wildest expectations. Within the course of one evening we had proved that exciting contemporary poetry could be presented really successfully. Soon, in response to Blue Nose’s track record of commitment and quality, GLA (later LAB) and Islington Borough agreed to support the project. Since then, there have been various changes. Mick Kinshott felt unable to continue as an organiser in 1990 and his commitment and humour was a great loss. His place was taken for two years by Bruce Barnes, whose knowledge of the poetry and arts funding world in London proved invaluable to the development of the project. More recently, Mimi Khalvati and Mario Petrucci have joined the three original members. In the middle of the Spring 1991 season, the Cafe where we held the events went into liquidation and a reading by Tom Pickard and Rosemary Norman sadly had to be called off. Regular events did not begin again until May 1991, when we moved into the more accessible, roomy and centrally located Market Tavern in Islington. Despite the many advantages of this new venue, there are a few who still regret the passing of the old Café which, though tiny, disorganised and terminally broke, did have a superb atmosphere for poetry.

In an appendix to this anthology, we list all the readers who have appeared at the venue/s – a genuinely comprehensive survey of poetry in recent years. This, of course, does not include the many poets who have had the opportunity to read from the floor at Blue Nose events. More importantly, this book contains no record of the hundreds and hundreds of people who have enjoyed and supported Blue Nose Poetry. This book is dedicated to them.

Martyn Crucefix / Sue Hubbard / Mimi Khalvati / Mario Petrucci / Denis Timm

Full List of Main/Support Readers for Blue Nose Poetry Seasons 1989 – 1993

March – July 1989

Michèle Roberts read with Martyn Crucefix; Philip Gross read with Sue Hubbard; Jeremy Silver read with Mick Kinshott; Jo Shapcott read with Denis Timm; Leo Aylen read with Gerda Mayer; Alison Fell read with Hume Cronyn; The Blue Nose Poets; Carole Satyamurti read with Barbara Zanditon; Michael Donaghy read with Rupert Slade; Adam Thorpe read with Al Celestine.

September – December 1989

Ken Smith read with Mimi Khalvati; Anna Adams and Julian May; Gerda Mayer read with Chris Powici; The Blue Nose Poets; The Performing Oscars; Maura Dooley read with Sara Boyes; Fred D’Aguiar read with Matt Caley; Matthew Sweeney read with Hilary Davies.

January – April 1990

Fleur Adcock read with John Harvey; Dannie Abse read with Myra Schneider; Elaine Randell read with Frances Presley; Hugo Williams read with Keith Spencer; Pitika Ntuli read with Bruce Barnes; John Cotton read with Bridget Bard; Michele Roberts read with Peter Daniels.

May – July 1990

The Blue Nose Poets; Sarah Maguire read with Vicki Feaver; Jeni Couzyn read with W N Herbert; James Berry read with Susan McGarry; Simon Armitage read with Chris Gutkind; E A Markham read with Mimi Khalvati; Brian Patten.

September – December 1990

In the Gold of Flesh anthology with Valerie Sinason, Dinah Livingstone, Pascal Petit, Jenny Vuglar; George Szirtes read with Gabriel Chanan; Kit Wright read with Candice Lange; The Blue Nose Poets; Michael Horovitz read with Raggy Farmer; Patience Agbabi and Judi Benson; Jenako Arts Writers; Carol Ann Duffy read with Steve Griffiths.

January – March 1991

Judith Kazantzis read with Mario Petrucci; Robert Creeley read with Mick Kinshott; Jackie Kay read with the Speech Painters; Peter Forbes and Eva Salzman; [Blue Nose Cafe in Highbury suddenly closes]; Lemn Sissay read with Adam Acidophilus.

May – July 1991

Peter Porter read with Elizabeth Garrett; The Blue Nose Poets; Carole Satyamurti read with Leon Cych; Peter Scupham read with Lucien Jenkins; Leo Aylen read with Rosemary Norman.

October – December 1991

Sylvia Kantaris read with Andrew Jordan; Gillian Allnutt read with Helen Kidd; Alan Jenkins read with Eric Heretic; Sean Street and Hubert Moore; Lee Harwood and Richard Cadell; Xmas Party – Tony Maude, Speech Painters and music from Dean Carter.

January – April 1992

Adrian Mitchell; David Constantine read with Tim Gallagher; David Morley with Martyn Crucefix; Sue Stewart read with Bruce Barnes; Glyn Maxwell read with Sue Hubbard; Peter Abbs read with Nicky Rice.

May – July 1992

Jo Shapcott read with Mick Kinshott; Bobbie Louise Hawkins read with Robert Sheppard; Birdyak – Bob Cobbing and Hugh Metcalfe; Colin Rowbotham read with Richard Tyrrell; Ken Smith read with Eric Heretic.

October – December 1992

Connie Bensley and Felicity Napier; The Poetry Show at Rebecca Hossack Gallery; Donald Atkinson read with Jane Duran; Ruth Fainlight read with Moniza Alvi.

January – April 1993

Peter Reading read with Briar Wood; Ruth Valentine; Myra Schneider read with Mario Petrucci; Carol Rumens read with Daphne Rock.

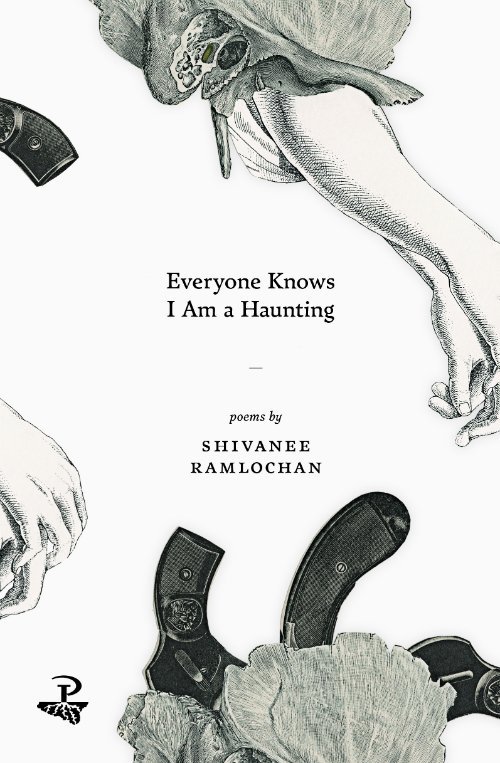

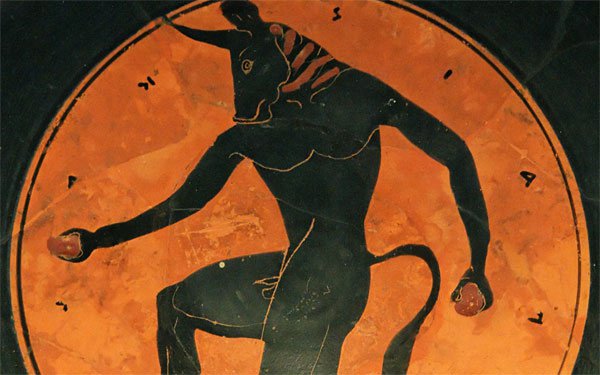

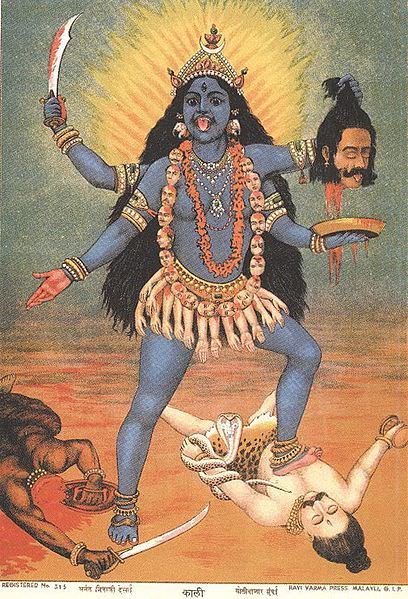

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

There is a sequence in the middle of the book which offers a clearer view of Ramlochan’s approach. ‘The Red Thread Cycle’, on the face of it, explores the traumatic consequences of rape. How to articulate the event is one theme and there is a magic-real quality which initially seems to add to the horror: “Don’t say Tunapuna Police Station. / Say you found yourself in the cave of the minotaur”. But this shifts quickly instead to reflect how police and authorities fail to take such a literal description seriously, even blaming the woman herself: “Say / he took something he’ll be punished for taking, not something you’re punished for holding / like a red thread between your thighs”. Other poems trace improvised rituals (real and semi-real) to expiate the crime and trace the passage of years. Some moments suggest the lure of suicide with allusions to Virginia Woolf’s death by water, carrying “pockets of white stones”. Seeing the unpunished rapist at large eventually becomes possible: “Nothing drowns you, when you see him again”. The sequence is a lot less chronological than I am making it sound, but what the woman has been doing over the years is, in a striking phrase, “working to train the flinch out of myself”. This has been achieved partly through art. Ramlochan certainly sees such pain as an essential part of the artist’s apprenticeship, that it will “feed your best verse”, and the sequence ends with her reading poems in public as an act of strength and self-affirmation, marking the psychic death of the aggressor: “applause, hands slapping like something hard and holy / is grating out gold halleluiahs / beneath the proscenium of his grave”.

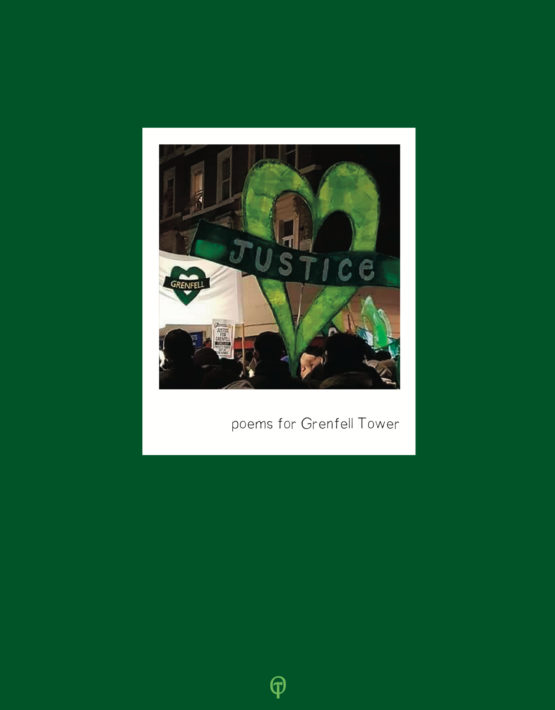

Then I have been reading poems for Grenfell Tower (The Onslaught Press) and picking away at some link between the (in)adequacy of a certain English poetic voice to confront the scale of ecological issues, or as a vehicle for expressing certain cultural differences, or as a way of exploring the kind of tragic and grievous event represented by the Grenfell fire and its aftermath. This struck me particularly as, in the Grenfell anthology, there are well-know poets alongside others less well-known, plus some who felt impelled to write as a direct result of the catastrophe. I felt many of the more well-known names struggled to find a sufficient voice for this appalling event, often sounding too careful, overly subtle, perhaps too concerned with Mort’s “linguistic originality”. Does such a devastating, large scale, well publicised event require a different kind of voice from poets?

Then I have been reading poems for Grenfell Tower (The Onslaught Press) and picking away at some link between the (in)adequacy of a certain English poetic voice to confront the scale of ecological issues, or as a vehicle for expressing certain cultural differences, or as a way of exploring the kind of tragic and grievous event represented by the Grenfell fire and its aftermath. This struck me particularly as, in the Grenfell anthology, there are well-know poets alongside others less well-known, plus some who felt impelled to write as a direct result of the catastrophe. I felt many of the more well-known names struggled to find a sufficient voice for this appalling event, often sounding too careful, overly subtle, perhaps too concerned with Mort’s “linguistic originality”. Does such a devastating, large scale, well publicised event require a different kind of voice from poets? The difficulties of addressing such a subject are expressed by Joan Michelson’s contribution which announces and extinguishes itself in the same moment: “This is the letter to the Tower / that I cannot write”. One of the best poems which does display evident ‘literary’ qualities is Steven Waling’s ‘Fred Engels in the Gallery Café’. It cleverly splices several voices or narratives together, one of these being quotes from Engels’ 1844 The Condition of the Working Class in England. Other fragments used allude to gentrification and the wealth gap in the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Other poems, like Pat Winslow’s ‘Souad’s Moon’, focus on the presence of refugees in the Tower, or the role of the profit-motive in the disaster (‘High-Rise’ by Al McClimens), or the presence of an establishment cover-up after the event (Tom McColl’s ‘The Bunker’).

The difficulties of addressing such a subject are expressed by Joan Michelson’s contribution which announces and extinguishes itself in the same moment: “This is the letter to the Tower / that I cannot write”. One of the best poems which does display evident ‘literary’ qualities is Steven Waling’s ‘Fred Engels in the Gallery Café’. It cleverly splices several voices or narratives together, one of these being quotes from Engels’ 1844 The Condition of the Working Class in England. Other fragments used allude to gentrification and the wealth gap in the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Other poems, like Pat Winslow’s ‘Souad’s Moon’, focus on the presence of refugees in the Tower, or the role of the profit-motive in the disaster (‘High-Rise’ by Al McClimens), or the presence of an establishment cover-up after the event (Tom McColl’s ‘The Bunker’). But more often than not, these poets opt for more tangential routes to expression. Other disasters – such as Nero watching Rome burn, the 1666 Fire of London, the bomb falling on Hiroshima and the Aberfan disaster – prove ways in for Abigail Elizabeth Rowland, Neil Reeder, Margaret Beston and Mike Jenkins. The naivety and innocence of a child’s eye is another common device. Andrew Dixon’s ‘Storytime’ takes this approach, the child’s language and vision allowing simple but nevertheless powerful statements: “Mama don’t be afraid. Do you / want us to pray? I know what / to say. We’re both in a rocket / and we’re going away.” Finola Scott does the same with a Glasgow accent, a child staring from her own tower block home: “she peers doon at hir building, wunners / Whit’s cladding?’ A young life cut off before its full development by the fire is also the theme of two poems that refer to the death of Khadija Saye. She was a photographer who died in the blaze, whose work had been exhibited in Britain’s Diaspora Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Michael Rosen’s contribution again uses childlike simplicity and obsessive repetition – as much representing a struggle to comprehend as the gnawing of realised grief:

But more often than not, these poets opt for more tangential routes to expression. Other disasters – such as Nero watching Rome burn, the 1666 Fire of London, the bomb falling on Hiroshima and the Aberfan disaster – prove ways in for Abigail Elizabeth Rowland, Neil Reeder, Margaret Beston and Mike Jenkins. The naivety and innocence of a child’s eye is another common device. Andrew Dixon’s ‘Storytime’ takes this approach, the child’s language and vision allowing simple but nevertheless powerful statements: “Mama don’t be afraid. Do you / want us to pray? I know what / to say. We’re both in a rocket / and we’re going away.” Finola Scott does the same with a Glasgow accent, a child staring from her own tower block home: “she peers doon at hir building, wunners / Whit’s cladding?’ A young life cut off before its full development by the fire is also the theme of two poems that refer to the death of Khadija Saye. She was a photographer who died in the blaze, whose work had been exhibited in Britain’s Diaspora Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Michael Rosen’s contribution again uses childlike simplicity and obsessive repetition – as much representing a struggle to comprehend as the gnawing of realised grief: