As in the previous five years, I am posting – over the summer – my reviews of the 5 collections chosen for the Forward Prizes Felix Dennis award for best First Collection. This year’s £5000 prize will be decided on Sunday 25th October 2020. Click here to see my reviews of all the 2019 shortlisted books (eventual winner Stephen Sexton); here for my reviews of the 2018 shortlisted books (eventual winner Phoebe Power), here for my reviews of the 2017 shortlisted books (eventual winner Ocean Vuong), here for my reviews of the 2016 shortlisted books (eventual winner Tiphanie Yanique), here for my reviews of the 2015 shortlisted books (eventual winner Mona Arshi).

The full 2020 shortlist is:

Ella Frears – Shine, Darling (Offord Road Books) – reviewed here.

Will Harris – RENDANG (Granta Books) – reviewed here.

Rachel Long – My Darling from the Lions (Picador)

Nina Mingya Powles – Magnolia 木蘭 (Nine Arches Press) – reviewed here.

Martha Sprackland – Citadel (Pavilion Poetry)

After her Gregory Award in 2014 and two chapbook publications since, Martha Sprackland has long been pondering those decisions about constructing a first full collection. (She talks briefly about that process here). Ought it to be a Rattle Bag of the best poems to date, or a more coherently shaped and organised ‘concept album’? Citadel is evidently being presented to readers as the latter – but with equivocal results. The first reference of the book’s blurb is to Juana of Castile, commonly referred to as Juana la Loca (Joanna the Mad), a 16th century Queen of Spain. She was daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, instigators of the Spanish Inquisition, but was conspired against, declared mad, imprisoned and tortured by her father, husband and her son, leaving almost no written record of her own. Sprackland – having studied Spanish and spent time in Madrid – presents herself as becoming fixated on this earlier woman, engaged in conversations with her to such a degree that (according to the blurb again) the poems in Citadel are written by a “composite ‘I’ – part Reformation-era monarch, part twenty-first century poet”.

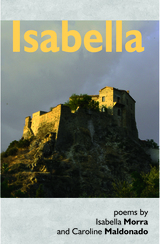

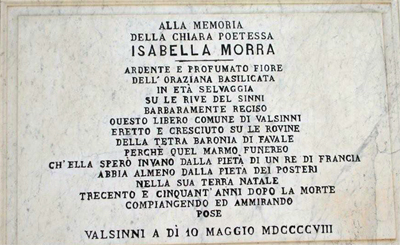

While happy to accept the desire of the poet to maintain a distance between the lyric/dramatic ‘I’ and her autobiographical self, I find the idea, the ‘as if’, of this composite authorship hard to take. There is even something disproportionate about the claim of identity between the two women, given the extremity of Juana’s life-long suffering. I’m reminded of Caroline Maldonado’s 2019 book, Isabella (Smokestack Books) in which she translates and writes poems to Isabella Morra, an Italian aristocrat of the 16th century who also suffered appalling hardship (and likely murder) at the hands of her male relations. But Maldonado’s interest in the historical figure is never claimed as an identity. (I reviewed this book here).

The awkwardness of the leap of faith in this alignment between Sprackland and Juana gives rise to several of the opening poems which seem to want to ‘explain’ empirically the (perfectly legitimately) imagined connection. ‘Beautiful Game’ is a family-holiday-in-Spain poem, in which the Martha figure (the collection does use its author’s name on several occasions) is hit on the head with a pool ball. The next but one poem takes this up. ‘A Blow to the Head’ takes the injury as a moment of profound psychological importance. The narrator is “cracked open” and in the same moment retreats into a psychological “citadel”. The protection this offers her becomes “habit-forming, I was fortified”. The latter pun is good and the poem suggests that it is in this state of defensive retreat, perhaps of ‘imprisonment’, that she passes through a portal, making first contact with “her”, Juana. One of the tortures that Juana faced, for her religious unorthodoxy, was la cuerda, being strung up with cord/rope, weights attached to her feet. In this poem, Martha loosens “the cord from her wrists”.

It’s the poem placed between these two that perhaps provides a further clue to the undoubtedly powerful link felt by Sprackland to Juana, the link between the personal and the historical. Much is left unsaid in ‘A Room in London’; the reluctance to reveal is part of the fortified ‘citadel’. In a vaguely defined medical environment there are several young women, one of them being given misoprostol (a drug used to induce abortion). Such a moment of profound emotional, physical and psychological experience must be the origins of the identification between two individuals so remote in time and Sprackland catches the paralleled shift of innocence to pained maturity in the brilliant final line: “Our little beds, bars of autumnal light falling through the curtains”.

The fact is that this identification of the two women does then give rise to several excellent (I’d describe them as uncanny) poems – though their existence does not need anything more by way of justification than a belief in language and the poetic imagination. In ‘They Admit Each Other to the Inquisitor’, the two women are bound together by the first-person plural pronouns: “We were eighteen and pregnant and mad”. The force and flow of the poem takes the reader quickly beyond questions of likelihood:

When we undid the cord that tied our wrists

it bound us; something in that blow

knocked through the city walls

and through it we are talking, still.

We can’t explain this.

The same device is used in ‘Juana and Martha in Therapy’; this time it’s the third person plural. They are as one and yet at the same time they are communicating down a cup-and-string telephone, made from a cord and two tins of cocido (chick-pea and meat stew). There is great humour here besides the serious experiment in imaginative identification: “Time is complicated, especially at these distances”. But also, Time can be collapsed into magically anachronistic moments of intimacy: “They are in the bland room / above the Pret in Bishopsgate, trying to understand. / The walls of the mind are deep and moated”. The final poem in Citadel is ‘Transcript’ which is a verbatim record of a conversation between the two women:

- i’ll sing you something, and you’ll sleep, tomorrow I will go falconing –

- and I will go to work and try to hold the yolk of myself together, try not to spill –

I wish there were more poems in the book in which this sort of unashamed, ludicrous, heartfelt and imaginatively suggestive communication was portrayed. There are a few other occasions where poems approach it, but the leap of faith required seems even too much for the poet and the results feel more willed than wholly convinced. Juana alone (though in the third person) appears to good effect in ‘Falconry’, an excellent poem that hovers, alongside the hunting bird, over the landscape of the Alhambra. The bird’s searching out of its prey represents the young Queen’s curiosity, her challenge to authority (that will soon get her into so much trouble), and its tearing up of a lark seems to foreshadow Juana’s own suffering.

Otherwise, Citadel contains plenty of poems more directly connected to what we might tactfully designate the author’s biography, poems which might have constituted a Rattle-Bag-style first collection. The five sections of ‘Melr’ read very autobiographically, a childhood in a village north of Liverpool: “I grew up coastal with the land to my back”. It’s portrayed as a place of shifting sands and, as teenage years advance, that sense of novelty-seeking (like Juana and deploying similar bird imagery) grows: “villagers heard / the clatter of the entire migratory flock / lifting off under cover of darkness”. Youthful experimentation, unpredictability and the allure of travel are all expressed in the excellent ‘Pimientos de Padron’. One imagines language students in Madrid, “lovesick, shamed or fleeing / or brisant and in shock”, then heading to the airport for “the first flight anywhere but home”.

There is a motif in the book of those brought up on sand finding it hard to settle. ‘Anti-metre’ suggest this even reaches the menstrual cycle which shifts, “mutable as a dune” and one recalls the clinical environment of ‘A Room in London’ when ‘Hunterian Triptych’ concludes with the narrator and her boyfriend running out in alarm at the sight of preserved foetuses in a museum, “ranged by month and weight”. I sense the Catholicism of Spain in general (and Juana’s wrestling with it, in particular) haunting Citadel. So a visit to an orthognathic surgeon is portrayed in terms of the confessional and a poem like ‘Charca’ is underscored by a baptismal or redemptive sense. A charka is a pool, here a natural bathing pool in a valley. The narrator and her friends go there and, beyond the hedonism and holiday pleasures, she finds something more profound shifting, beginning to lift and heal into freedom:

Something frozen

and distant starts to thaw in me

and to carve these deeper channels

into which we jump, again and again,

looked over by nothing but the mountains,

the overhanging leaves,

the lifted winter lived through and unbound.

This might suggest ‘Martha’ already outgrowing the need to speak to Juana. Another poem like ‘Still Life Moving’ – for me one of the best in the book – suggests the poet’s concern for Time as a theme, that “complicated” thing, here matched with Art (a still life, perhaps in the Prado) and, as time the destroyer creeps into the frame, rotting the lilies and spilling the apples, she utters a cry for some form of redemptive salvation, whether from God or Juana or elsewhere:

Are there hands, just out of the frame,

that might dart forward in time to catch them?

I’m not proud to admit that Way More Than Luck passed me by when it was first published. As you are probably aware, Wilkinson reviews poetry regularly for The Guardian, and he’s very familiar on social media as a poet and critic, a distance runner and a passionate Liverpool football fan. But the book’s cover (Dalglish, I think), its title and some of the publicity persuaded me that the football bit was going to be predominant. It’s certainly an almost unique aspect of the collection, but it turns out the debilitating darkness of psychological depression is an even more significant one. Wilkinson signals this concern via the book’s two epigraphs. One is about the nature of depression

I’m not proud to admit that Way More Than Luck passed me by when it was first published. As you are probably aware, Wilkinson reviews poetry regularly for The Guardian, and he’s very familiar on social media as a poet and critic, a distance runner and a passionate Liverpool football fan. But the book’s cover (Dalglish, I think), its title and some of the publicity persuaded me that the football bit was going to be predominant. It’s certainly an almost unique aspect of the collection, but it turns out the debilitating darkness of psychological depression is an even more significant one. Wilkinson signals this concern via the book’s two epigraphs. One is about the nature of depression

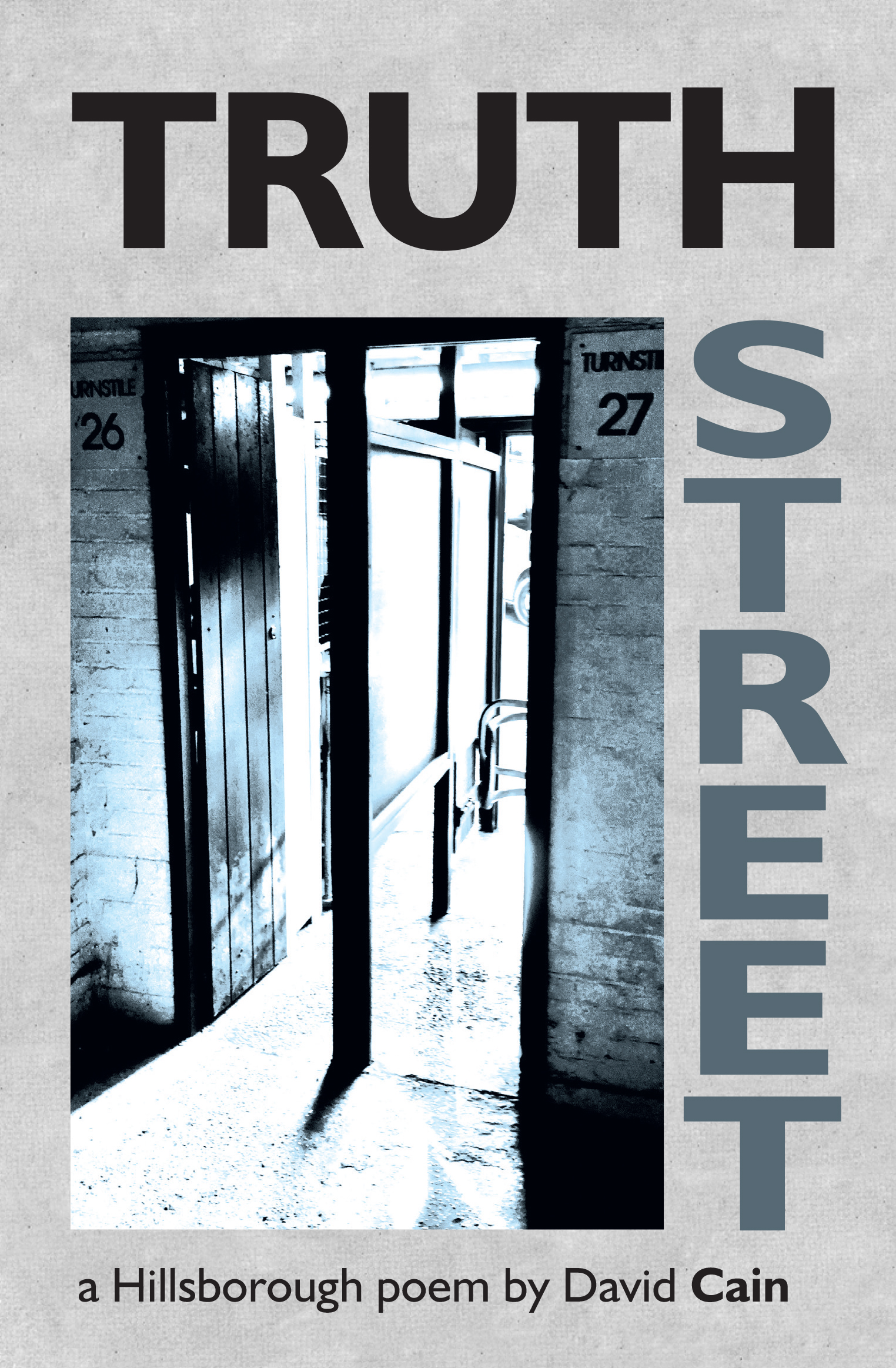

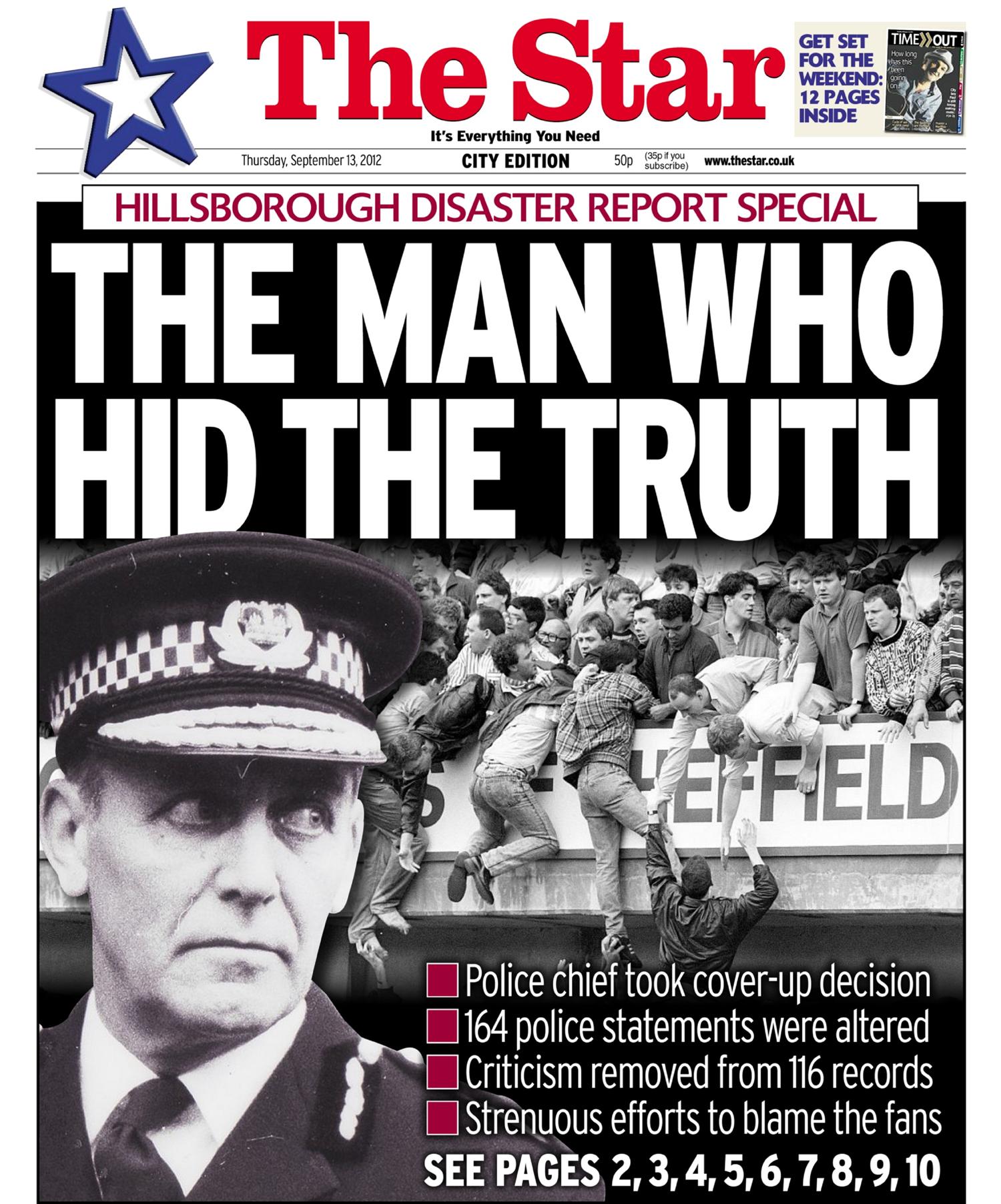

For me, it’s these psychological truths that Wilkinson is so good at conveying. There are other poems later in the book (and perhaps ‘Stag’ is an elusive example) which begin to sketch episodes of a foundering romantic relationship and ‘Building a Brighter, More Secure Future’ is a very effective excursion into witty political satire (a skilfully handled sestina based on the Conservative Party election manifesto, 2015). And there are the football poems. They comprise the central sequence of 14 poems, introduced with a heart-felt Prologue that says what follows is for the ordinary football fans, written out of “a love beyond the smear campaigns, / the media’s hooligans”. A large part of what Wilkinson has in mind here is the shocking response in parts of the media to the Hillsborough tragedy in 1989, when 96 men, women and children died (David Cain’s Forward prize shortlisted book, Truth Street, from Smokestack Books, movingly dealt with this event and the media and policing responses and

For me, it’s these psychological truths that Wilkinson is so good at conveying. There are other poems later in the book (and perhaps ‘Stag’ is an elusive example) which begin to sketch episodes of a foundering romantic relationship and ‘Building a Brighter, More Secure Future’ is a very effective excursion into witty political satire (a skilfully handled sestina based on the Conservative Party election manifesto, 2015). And there are the football poems. They comprise the central sequence of 14 poems, introduced with a heart-felt Prologue that says what follows is for the ordinary football fans, written out of “a love beyond the smear campaigns, / the media’s hooligans”. A large part of what Wilkinson has in mind here is the shocking response in parts of the media to the Hillsborough tragedy in 1989, when 96 men, women and children died (David Cain’s Forward prize shortlisted book, Truth Street, from Smokestack Books, movingly dealt with this event and the media and policing responses and  But the poems also show how difficult it is to escape the miasma of cliché that seems to engulf football itself. Anfield is filled with a “fabled buzz”, then “the place erupt[s]”. Barnes unleashes a “a sweeping, goal-bound ball”, and a particular game offers one “last-ditch twist”. I’m reminded of Louis MacNeice’s observation (now sadly compromised in various ways, but the spirit of it remains valid, I think) that he wanted a poet not to be “too esoteric. I would have a poet able-bodied [sic], fond of talking, a reader of the newspapers, capable of pity and laughter, informed in economics, appreciative of women [sic], involved in personal relationships, actively interested in politics, susceptible to physical impressions’. There are many more of these poets around these days and to bring (even) football into the purview of poetry can hardly be a bad thing. Yet it is not an easy one and there may be some risks in deciding to headline the attempt. Ian Duhig’s blurb note to Way More Than Luck has gingerly to negotiate this issue: “The beautiful game inspires some beautiful poems in Ben Wilkinson’s terrific debut collection … but there’s far more than football to focus on here”. Yes, indeed.

But the poems also show how difficult it is to escape the miasma of cliché that seems to engulf football itself. Anfield is filled with a “fabled buzz”, then “the place erupt[s]”. Barnes unleashes a “a sweeping, goal-bound ball”, and a particular game offers one “last-ditch twist”. I’m reminded of Louis MacNeice’s observation (now sadly compromised in various ways, but the spirit of it remains valid, I think) that he wanted a poet not to be “too esoteric. I would have a poet able-bodied [sic], fond of talking, a reader of the newspapers, capable of pity and laughter, informed in economics, appreciative of women [sic], involved in personal relationships, actively interested in politics, susceptible to physical impressions’. There are many more of these poets around these days and to bring (even) football into the purview of poetry can hardly be a bad thing. Yet it is not an easy one and there may be some risks in deciding to headline the attempt. Ian Duhig’s blurb note to Way More Than Luck has gingerly to negotiate this issue: “The beautiful game inspires some beautiful poems in Ben Wilkinson’s terrific debut collection … but there’s far more than football to focus on here”. Yes, indeed.

Cain also cites the work of Charles Reznikioff and Svetlana Alexievich as models. The former, an Objectivist poet, developed work from

Cain also cites the work of Charles Reznikioff and Svetlana Alexievich as models. The former, an Objectivist poet, developed work from

In fact – as Cain’s sequence shows – what was being covered up was the original decision of Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield to open the exit gates at 2.47pm. One of his officers spoke to the inquiry: “I was quite shocked // It was totally unprecedented. // It was something you just didn’t do”. This was what caused the inflow of fans – “like sand into an egg timer”. Only at the second inquiry, did Duckenfield revise his earlier false statements: “I didn’t say, // ‘I have authorised the opening of the gates’”.

In fact – as Cain’s sequence shows – what was being covered up was the original decision of Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield to open the exit gates at 2.47pm. One of his officers spoke to the inquiry: “I was quite shocked // It was totally unprecedented. // It was something you just didn’t do”. This was what caused the inflow of fans – “like sand into an egg timer”. Only at the second inquiry, did Duckenfield revise his earlier false statements: “I didn’t say, // ‘I have authorised the opening of the gates’”.