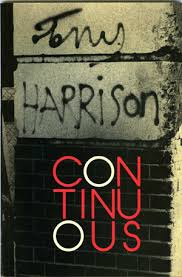

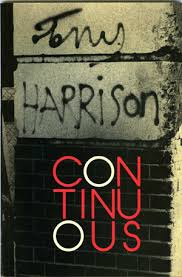

Last week I posted on Tony Harrison’s ‘A Cold Coming’. The following discussion of another extraordinary Tony Harrison poem originally appeared in book form in Tony Harrison: Loiner (Clarendon Press, 1997), edited by Sandie Byrne.

‘Them and [uz]’ – listen to Harrison read this poem here.

for Professors Richard Hoggart & Leon Cortez

I

αίαι, ay, ay! … stutterer Demosthenes

gob full of pebbles outshouting seas –

4 words only of mi ‘art aches and … ‘Mine’s broken,

you barbarian, T.W.!’ He was nicely spoken.

‘Can’t have our glorious heritage done to death!’

I played the Drunken Porter in Macbeth.

‘Poetry’s the speech of kings. You’re one of those

Shakespeare gives the comic bits to: prose!

All poetry (even Cockney Keats?) you see

‘s been dubbed by [Λs] into RP,

Received Pronunciation, please believe [Λs]

your speech is in the hands of the Receivers.’

‘We say [Λs] not [uz], T.W.!’ That shut my trap.

I doffed my flat a’s (as in ‘flat cap’)

my mouth all stuffed with glottals, great

lumps to hawk up and spit out… E-nun-ci-ate!

II

So right, ye buggers, then! We’ll occupy

your lousy leasehold Poetry.

I chewed up Littererchewer and spat the bones

into the lap of dozing Daniel Jones,

dropped the initials I’d been harried as

and used my name and own voice: [uz] [uz] [uz],

ended sentences with by, with, from,

and spoke the language that I spoke at home.

RIP, RP, RIP T.W.

I’m Tony Harrison no longer you!

You can tell the Receivers where to go

(and not aspirate it) once you know

Wordsworth’s matter/water are full rhymes,

[uz] can be loving as well as funny.

My first mention in the Times

automatically made Tony Anthony!

Read about the drafting of this poem – in the Tony Harrison Archive at Leeds University.

Though it was Keats’ ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ Harrison ‘mispronounced’ at school, it is actually Wordsworth who is more important to him because both share a belief in poetry as the voice of a man speaking to men. This conception of poetry as speech is a powerful constituent in Harrison’s work and perhaps one not clearly understood. John Lucas, for example, has attacked what he sees as loose metrics in the poem ‘V’ but, to reverse Harrison’s comment that all his writing (theatrical or otherwise) is poetry, all his poetry needs to be read as essentially dramatic and deserves to be tested in the spoken voice as much as in the study. Harrison’s interest in the curious idea that the true poet is born without a mouth implies the difficult battling for a voice or voices which can be found everywhere in his work and it is in this clamour that I find its dramatic quality. In a public poem like ‘A Cold Coming’, Harrison makes use of the contrasting and conflicting voices by playing them off against a regular form. This is almost always the case, but in what follows I prefer to concentrate less on metrical effects than on the way voices interweave.

The very title of the pair of sonnets, ‘Them & [uz]’, seems to promise conflict, at best dialogue, and it opens with what could be taken as the howl of inarticulacy. In fact each pair of these opening syllables gestures towards crucial worlds in Harrison’s universe. The ‘αίαι’ of classical dramatic lament is echoed by the “ay, ay!” of the musical hall comedian cheekily working up an audience. Immediately, the reader is plunged into the unresolved drama of two differing voices, instantly implying the two cultures of the sonnets’ title. The line and a half which follows, sketching Demosthenes practicing eloquence on the beach, is intriguing in that its locus as speech is hard to pin down. It is perhaps intended at this stage (apart from introducing the poems’ central issue) to hover in an Olympian fashion above the ruck of dialogue that follows, implying the heroic stance which will be taken up in the second sonnet.

Line 3 opens again into a dramatic situation with the voice of the narrator (the adult Harrison), repeating his own interrupted recital of Keats in the classroom, while the master’s scornful comments appear fresh, unreported, as if still raw and present, in speech marks. The narratorial comment on this – “He was nicely spoken” – confirms this poem’s tendency to switch voices for its effects, this time its brief sarcasm barely obscuring the unironic comment likely to be made by an aspiring Loiner, or by an ambitious parent. The example of nice speaking given (again in direct quotes in the following line) is the master’s claim to possession, to authority in matters of language and culture and the separated-off reply of the narrator – “I played the Drunken Porter in Macbeth – with its full rhyme and sudden regular iambic pentameter, implies both a causal link between the two lines, painting Harrison as dispossessed specifically by the master’s attitudes, as well as conveying the tone of resignation in the young schoolboy.

Much of the tension and success of the poem has already arisen from the dramatic interchange of voices and the master’s voice asserts itself again in line 7 ironically claiming a kind of monolithic, aristocratic purity to poetry which this poem has already attempted to subvert:

Poetry’s the speech of kings. You’re one of those

Shakespeare gives the comic bits to: prose!”

The following lines contain a curious wavering in the clear interplay of dramatic voices, only part of which is resolved as the poem proceeds. Evidently, the intrusive, even hectoring, parenthesis (at line 9) is the narrator’s questioning of what appears to be the master’s voice’s continuing argument that “All poetry” belongs to Received Pronunciation. Yet the aggression of this attack, with its harsh alliteration and sarcastic question mark, is out of key with the other narratorial comments in part I, though the tone is re-established in part II. In addition, I have some difficulty in accepting the master’s words as appropriate to the situation which – with no break – continues the speech made to the young Harrison. For example, the word “dubbed”, with its implication of the deliberate laying of a second voice over an ‘original’, already hands victory in the argument to Harrison’s claim for the authenticity of ‘dialect’ and, as such, would not be used by the believer in “the speech of kings”. Equally, the apparent plea, “please believe [ s] / your speech is in the hands of the Receivers”, does not accord with the voice that summarily dismissed the pupil as a “barbarian” 7 lines earlier. In this case, Harrison’s desire for the dramatic has foundered momentarily on that old dramatist’s rock, the necessity for exposition which compromises the integrity of the speaking voice.

The true note of the master returns – interestingly, following one of Harrison’s movable stanza breaks, as if confirming a shift in voice though the speech actually continues across the break – with “We say [Λs] not [uz], T.W.!” The tone of the responding voice, after the suggestion of a more spirited response in the Keats comment, has returned to the resignation of the brow-beaten pupil. This is reinforced by the more distant comparison of the boy to the ancient Greek of the opening lines, heroically “outshouting seas”, while the young Harrison’s mouth is “all stuffed with glottals, great / lumps to hawk up and spit out”. This first sonnet draws to a close with this tone of frustrated defeat for the boy, yet the drama has one final twist, as the voice of the master, sneering, precise and italicised, has the last word – “E-nun-ci-ate!“. There can be little doubt that the boy must have felt as his father is reported to have done in another sonnet from The School of Eloquence, “like some dull oaf”.

The second part of ‘Them & [uz]’ contrasts dramatically with the first, though the seeds of it lie in the image of heroic Demosthenes and the accusatory tone of the reference to Keats which seemed a little out of place in part I. This second sonnet’s opening expletive aggression strikes a new tone of voice altogether. “So right, yer buggers, then! We’ll occupy / your lousy leasehold Poetry”. The poem’s premise is that it will redress the defeat suffered in part I in an assertive, unopposed manner. Not the master, nor any spokesman for RP is allowed a direct voice, yet the interchange of speech and implied situation can still be found to ensure a dramatic quality to the verse.

The passionate and confrontational situation of the opening challenge is clear enough, yet it’s striking how it has taken the autobiographical incident in part I and multiplied it (“yer buggers . . . We’ll occupy”) to present the wider political and cultural context as a future battlefield. Even so, there is no let up in the clamour of voices raised in the poem. Immediately, the narratorial voice shifts to a more reflective, past tense (at line 3) as the rebel reports actions already taken – and with some success, judging from the tone of pride and defiance: “[I] used my name and own voice: [uz] [uz] [uz]”. Even within this one line, the final three stressed syllables are spat out in a vivid reenactment of Harrison’s defiant spoken self-assertion. It is this slippery elision of voice and situation which creates the undoubted excitement of these and many of Harrison’s poems as they try to draw the rapidity and short-hand nature of real speech, its miniature dramas and dramatisations into lyric poetry. A further shift can be found in lines 9 and 10, in that the voice now turns to address a different subject. The addressee is not immediately obvious as the staccato initials in the line are blurted out in what looks like a return to the situation and voice with which this sonnet opened. Only at the end of line 10 does it become clear that the addressee is the poet’s younger self, or the self created as the “dull oaf” by the kind of cultural repression practised by the schoolmaster. The reader is further drawn into the drama of the situation by this momentary uncertainty: RIP RP, RIP T.W. / “I’m Tony Harrison no longer you!”.

The remaining 6 lines are, as a speech act, more difficult to locate. There is an initial ambiguity in that they may continue to address “T.W.”, though the stanza break suggests a change and, anyway, this makes little sense as T.W. is now dead (“RIP T.W.”). In fact, these lines use the second person pronoun in the impersonal sense of ‘one’, addressing non-RP speakers in general, and it is the generalised nature of these lines which disarms the effectiveness of the passage. This is particularly important in line 14, “[uz] can be loving as well as funny”, the tone of which, commentators like John Haffenden have questioned. The difficulty here is that if Harrison is addressing those who might use [uz] anyway, though there may well be many amongst them for whom the fact that “Wordsworth’s matter / water are full rhymes” is useful ammunition and reassurance, the same cannot be said of the “loving as well as funny” line which might variously be construed as patronising, sentimental or just plain unnecessary. Nevertheless, the poem regains a more sure touch in the final lines in its use of the reported ‘voice’ of The Times in renaming the poet “Anthony“. The effect here is both humorous (this, after all the poet’s passionate efforts!) and yet ominous in that the bastions of cultural and linguistic power are recognised as stubborn, conservative forces, still intent on re-defining the poet according to their own agenda, imposing their own hegemonic voice where there might be many.