When Shearsman Books published my translations from the German of Peter Huchel’s 1972 collection These Numbered Days (Gezählte Tage), we were still in the early days of Covid restrictions and so launch events and so on were very difficult. I was pleased when the book was recognised in 2020 by winning the Schlegel-Tieck Prize for translation from German awarded by the Society of Authors. The judges were Steffan Davies and Dora Osbourne. Yet the wheels of reviewing such books turn very slowly. And I am pleased once more with the appearance of a lengthy review of the book by Frank Beck which has recently appeared in the excellent journal, The Manhattan Review, edited by Philip Fried. So, with due acknowledgements, I am reproducing Frank’s review here. Do check out his work and visit The Manhattan Review, an excellent US journal with a liking for pubishing reviews and work from the UK.

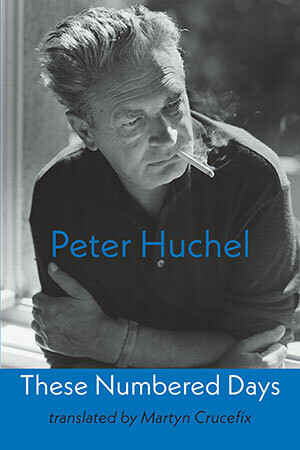

These Numbered Days (Gezählte Tage) by Peter Huchel, translated from the German by Martyn Crucefix and introduced by Karen Leeder. Emersons Green, Bristol, UK: Shearsman Books, 2019. 129 pp. $18.00 (paperback).

When poets look to the stars, often they are hoping to place their human worries in a wider context, in search of consolation. But what if they find, instead, that their concerns are reflected somehow in the sky overhead? Think of the famous fragment from Sappho: alone and unhappy, she watches the moon and the Pleiades descend together, like lovers lying down in bed. Readers may feel that something similar is happening in these lines from German poet Peter Huchel, as translated by British poet Martyn Crucefix:

Bent already by the night

into his icy harness,

Hercules drags

the star’s chain-harrow

up the northern sky. (p. 23)

When have we felt so much heft in the distant stars? We might well wonder what weight Huchel himself was bearing when he wrote this last stanza of his poem, “Under the Constellation of Hercules” (Unterm Sternbild des Hercules).

But first, let’s see how closely the English translation corresponds to the German stanza. Crucefix replicates Huchel’s pattern of three-beat lines, varied in line 3 with a two-beat phrase. He also makes use of the ready echoes some of Huchel’s words have in English: bent for gebeugt and icy for eisige. He creates a harsh music with chain-harrow, as does the clutter of consonants in Huchel’s Kettenegge. And Crucefix ties the stanza together with the r-sounds running through each of his five lines.

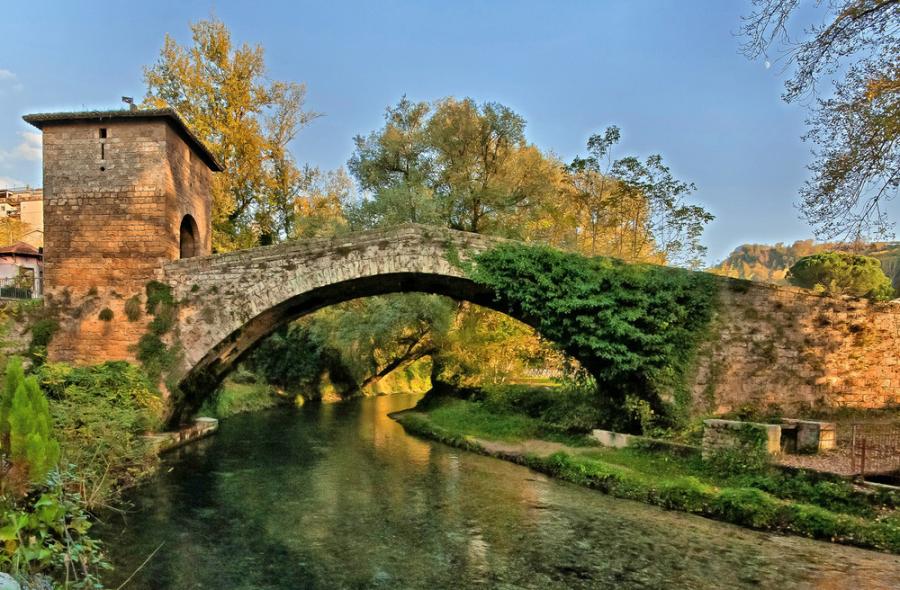

Of course, acoustics aren’t everything: this closing stanza owes much of its power to the two, less portentous preceding stanzas, in which the speaker describes a small, rural settlement, “no larger/than the circle/a buzzard traces/in the evening sky.” All we are shown of the place is a rough stone wall, “glittering water,” and the smoke from a fire, “cut through with voices,/none of which you know.” This sense of elemental conflict prepares us for the star-hauling of the final lines: even in the heavens, it seems, the grinding struggles of the universe go on.

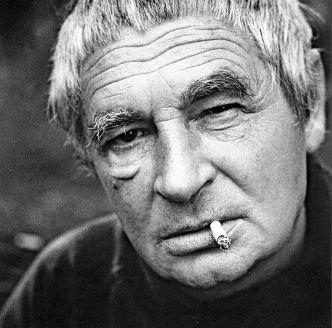

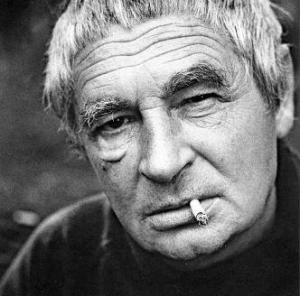

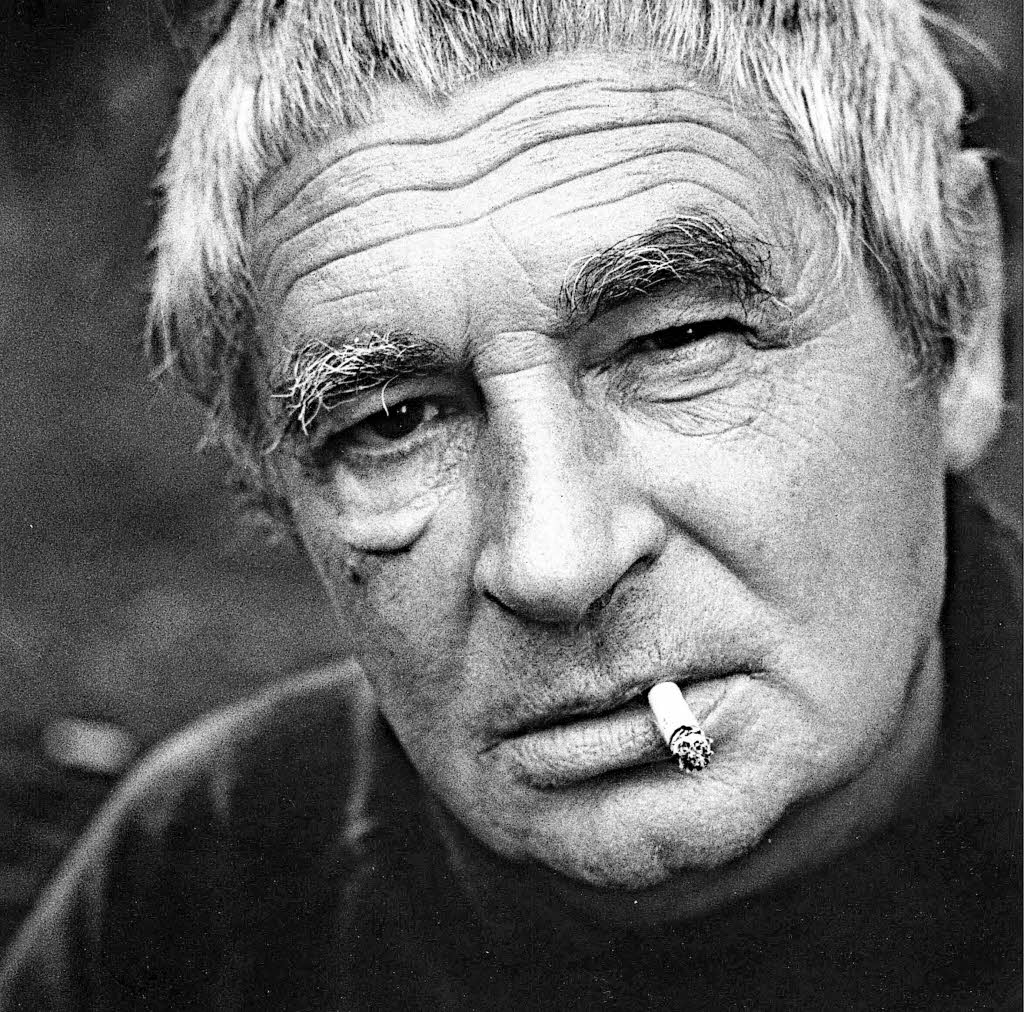

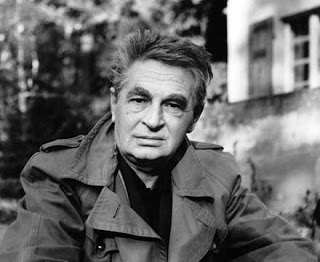

In the German-speaking world, Peter Huchel is widely considered one of the finest 20th-century poets. He composed many of his poems out loud, rather than on paper, so their resonant language often seems, in the words of one critic, “as natural as air or breath.” Huchel is also admired for the way he endured years of harassment and confinement at the hands of the East German government. His reputation was consolidated in 1984, when Huchel’s poetry and prose were collected in two volumes, meticulously annotated by Axel Vieregg, a German scholar in New Zealand who had spent decades studying the poet’s work.

English translations of Huchel’s poems have been difficult to find, although selections of them were compiled and translated by Michael Hamburger and Canadian poet Henry Beissel. (This despite Joseph Brodsky’s enthusiastic endorsement of Huchel’s poetry in The Wilson Quarterly in 1994, accompanied by translations by Joel Spector and a full-scale biography by British scholar Stephen Parker, in 1998.)

These Numbered Days brings us graceful English versions of all 63 poems in Huchel’s 1972 collection, Gezählte Tage, the fourth of his five verse collections, published between 1948 and 1979. The translated poems appear side-by-side with the German originals. An introduction by Karen Leeder helps orient the English-speaking reader in Huchel’s world, while connecting his work with the most urgent issues of today. Crucefix’s fidelity to both the meaning and the manner of Huchel’s poems won his book the prestigious Schlegel-Tieck Prize for German Translation in 2020.

Huchel was born Hellmut Huchel in 1903 (the “u” is pronounced like the double vowel in moon), the son of a civil servant and his wife, from Lichterfelde, a Berlin suburb. Hellmut spent much of his youth on his grandfather’s farm in the nearby Brandenburg countryside, where he developed a feeling of deep kinship with the natural world. After studying literature and philosophy briefly, he lived in Paris for two years, then traveled extensively in Hungary, Romania, and Turkey.

In 1931, at the age of 28, Huchel returned to Berlin, first earning his living as an editor and then by writing plays for radio. He changed his first name to Peter and began to publish his poems in Die literarische Welt and other leading German journals. Those early lyrics often draw on his memories of country life, as in “Havelnacht,” which describes a night on the Havel River in Brandenburg. Here are the poem’s last two stanzas (my translation):

Scents of so many past years

lean gently here, into the water.

As we go quietly along,

the night’s brew blows through us.

The greened stars are floating

as they drip from the oars.

And the wind cradles our lives,

as it cradles willow and crane.

As beguiling as these images are, the poem’s effectiveness depends largely on its delicately deployed A/B/A/B rhyme scheme, which I have not tried to replicate. (The German poem might remind an English-speaker of Yeats.) Already, Huchel had acquired the technical mastery that the Swiss critic Paul Schorno would later describe as “certainty of what is being said through certainty of form.”

In 1941 Huchel was drafted into the Luftwaffe, where he served until being taken prisoner by the Russians. This led to his working for Radio Berlin in the Russian-occupied sector after the war; eventually he became its cultural director. In 1949, when the Federal Republic of Germany was established in western Germany and the German Democratic Republic in the east, Huchel was named editor-in-chief of the GDR’s new literary magazine, Sinn und Form (Sense and Form). Under his direction, it came to play an important role in East German culture and even earned an international reputation.

However, Huchel’s interest in the diverse contemporary poetry flourishing abroad in those years was fundamentally at odds with Communist Party ideology, and he repeatedly came into conflict with party officials. In 1962, as East Berlin was sealed off from the West by a wall, Huchel was dismissed as editor of Sinn und Form. He was forbidden to publish in East Germany or to travel, and, along with his wife, Monica, a translator of Russian, and their son Stefan, was placed under round-the-clock surveillance at their home in Wilhelmshorst, near Potsdam.

The poems in These Numbered Days were written during the subsequent nine years, as Huchel remained under virtual house arrest. (Several of them were published in West Germany during the poet’s confinement; others appeared in English-language journals in Henry Beissel’s translations.)

In these poems, the rich, rhyming music of Huchel’s early poems is replaced by a spare but flexible flow of language that can contract to a beat or two or relax into longer lines. One of the book’s finest poems considers how the work of “The Dipper” (Die Wasseramsel), a small bird that feeds along the banks of rushing streams, resembles the poetry Huchel now wants to create:

If I could plunge

brighter downwards

into the flowing darkness

about me to fish out a word

like this dipper

beside the alder boughs

picks its food

from the stony river bed.

Gold-panner, fisherman,

relinquish all your gear.

The shy bird

looks to work without a sound. (p. 45)

Few poems in the collection deal with the Huchels’ troubles overtly. When they do, the tone is wry, refusing to reward oppression with anger. Even as the house around him deteriorates, presumably because repairs are not permitted, the poet declares, “I will not write/the names of my enemies/on the spongy wall” (“Weeds”). One has the sense of a man and his poetry being tested and determined not to fail. That includes trying to heed the advice offered to Huchel in a song by his friend, Wolf Biermann: “Do not become embittered/in this embittered time.”

Huchel’s few visitors in Wilhelmshorst had to subject themselves to police surveillance, with all the attendant risk in such a police state, or to approach in secret, under cover of darkness, as Huchel describes in “Weeds”:

Guests are always welcome,

those who love weeds,

those who do not shy away from stony paths

over-grown with grass.

No one comes.

The coalmen come —

from their filthy baskets they pour

the lumpen black grief

of earth into my cellar. (p. 123)

Huchel is still the keen observer of nature he was in his earlier books, but the natural world that once buoyed and nourished him now often mirrors his constricted situation, as in “Exile”:

Come evening, friends close in,

the shadows of hills.

Slowly they press across the threshold,

darkening the salt,

darkening the bread

and with my silence they strike up a conversation.

Outside in the maple

the wind stirs:

my sister, the rainwater

in the chalky trough,

imprisoned,

gazes up at the clouds. (p. 27)

Yet such confessions — even any use of personal pronouns — are scarce in these poems. Sometimes main verbs disappear, and the lines rely on gerunds and participles to move them forward. What is always present is Huchel’s patient watchfulness, often refracted through history and myth, as in his image of Hercules climbing the winter sky. With all roads around one blocked, the mind’s pathways become more important than ever, and allusions abound here. These poems reach out to the poet Alcaeus (a contemporary of Sappho), Tang dynasty writer Pe-Lo-Thien, Shakespeare, Kierkegaard, Virginia Woolf and other writers past and present.

Another connection that sustains Huchel, though more fleetingly, is his memory of happier times, especially his travels in the Mediterranean, as in “Dolphins”:

Gazing out across the sea

in white sunlight

I saw them leap

above the salty

weight of the water —

dolphins,

my secret brothers,

carrying my messages to Byzantium. (p. 91)

Such flashes of joy are tempered by the narrow confines of the Huchels’ lives. In “Hubertusweg” (the name of their street), the poet wonders about the policeman standing guard outside his house in the rain (“What’s in it for him . . . ?”) and then considers the vulnerability of each person before a totalitarian state (“The state’s a blade;/the people thistles.”) Yet even totalitarian states have a life-span. Huchel sees his son reading a cuneiform text about “the peaceful campaign” of the Bronze Age ruler, King Keret, and his poem concludes:

On the seventh day,

as the God IL proclaimed,

a hot wind blew and drank the wells dry,

the dogs howled,

the donkeys cried out with thirst.

And without the use of a battering ram the city surrendered. (p. 121)

In 1971, in response to efforts by Heinrich Böll, Arthur Miller, Henry Beissel and others, the GDR allowed Peter Huchel and his family to emigrate to West Germany. He continued to write there until his death, in 1981. Eight years later, the Berlin Wall fell without a shot’s being fired, and Germany was soon reunited. The Huchels’ house in Wilhemshorst, where these poems were written, is now a writer’s center, sponsored by the state and local governments.

Today the once-divided city of Berlin is one of the most vibrant places in the world. Huchel’s poetry is still in print and still read, and, at number 10, Hanseatenweg, near the Tiergarten, Sinn and Form keeps producing new bimonthly issues, very much along the editorial lines Huchel had in mind. Thus far this year, alongside work by and about German-language writers, the journal offered its readers articles about Jorge Luis Borges, Clarice Lispector, Marcel Proust, Marina Tsvetaeva, and Adam Zagajewski.

—Reviewer Frank Beck is a writer and translator and serves as a trustee for Elgar Works, which publishes the scores of Edward Elgar. His recent thoughts on poetry and music can be found at WWW.DIEHOREN.COM.