The sad news that Jürgen Becker (1932-2024) died recently at the age of 92 was particularly poignant as I have been translating his work for the past 3 years. I first read about his poetry in an essay I was translating by Lutz Seiler (published in In Case of Loss (And Other Stories, 2024)). There, Seiler characterises Becker’s work as ‘a process that integrate[s] both immediate and more distant modalities of language, his own voice as well as materials drawn from other sources such as events, photos, maps as well as interjections from neighbouring rooms, from the mail, the news, weather conditions and whatever else stray[s] within range’ (my translation). History, politics, the importance of recording ‘small things’, an extraordinarly porous kind of poetry – these were the aspects that drew me to his work (as a writer of my own poems as much as translator).

Becker’s ‘typical’ poem works at length, resembling a stream-of-consciousness, but better thought of as a kind of collage or montage. His effects are slow-burning, allusive, even elusive, and I don’t think his work is likely to top any UK chart of popular poetry any time soon. But his revered status in Germany is remarkable and I have actually had a couple of successes recently with my translations: a Highly Commended in the 2024 Stephen Spender Trust Translation Competition, judged by Taher Adel and Jennifer Wong (with the poem ‘Meanwhile in the Ore Mountains’), and one of Becker’s longer poems in translation being published (‘Travel film; re-runs’ – see below).

Becker grew up in the German region of Thuringia which, after World War II, was in the Soviet occupation zone, later the GDR. By then, his family had moved to West Germany and, after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990, the writer often returned to his childhood landscape. I have concentrated my translation efforts on Becker’s 1993 poems in Foxtrot in the Erfurt Stadium, published by Suhrkamp. The full translation is due to be published by Shearsman Books in 2025. The Spender Trust Competition poem is a short piece which I can quote in full. The Competition requires entrants to say a few words about the poem and the translation process. Here is a video of the Intro and Reading of the poem for the prize event, and (alongside) the text that I originally submitted:

Commentary – The Ore Mountains lie along the Czech-German border. Borders are important in this poem. Born in the East German region, brought up in West Germany, after the fall of the Wall in 1990, Becker often returned to his childhood landscape. Though relatively brief, this poem is just one sentence, woven together with the conjunction ‘wie’ (translated here both as ‘how’ and ‘the way’). The weave is dense and it’s not possible to tell whether what is observed – the children, the oil spill, the tree stump (resembling a body) – are contemporaneous or from different eras. My translation keeps these possibilities open: borders here are temporal, as well as geographical. The German word ‘Avantgarde’ has artistic as well as political implications, but my choice of ‘vanguard’ also brings out the militaristic connotations which are reinforced by the ‘spitzen, grünen Lanzen’ (‘sharp, green spears’) which are swiftly transformed into a bunch of sprouting snowdrops. These flowers of Spring are referred to as a ‘Konvention’ and I retained the English equivalent, intending to suggest both a performance (something conventional, perhaps not genuine), as well as a political gathering or agreement (like the Convention on Human Rights). The ambiguity felt relevant. The final vivid, visual images – a TV screen seen through a window, a script on the screen, a woman talking, but inaudible to the observer – sum up Becker’s concerns about the media, political and historical change, borders real and imagined, exclusion, and the need to ask questions of those in power. Issues as real today as when the poem was written.

Meanwhile in the Ore Mountains

Sitting still, watching how the afternoon below

waits for the dusk, the way snipers vanish

behind the remains of a wall and children run

after a white, armoured vehicle, the way a line

of hills, which marks a boundary, divides

the nothingness of snow from the nothingness of sky,

and along the frontier, one this side, another

along the other, fly the only two crows

to be found in this treeless landscape, the way

the iridescent pattern of an oil spill develops

with darkening edges, the way a tree stump

in the field becomes the shape of a body with

severed arms and legs, how, under the cherry,

the vanguard shows with sharp, green spears,

which later, over the next few days, assumes

the convention of snowdrops, how dark windows

are lit by screens, and on each screen appears,

at first, lettering, and then the face of

a woman who is soundlessly moving her lips.

The longer poem – ‘Travel film; re-runs’ – which does indeed run to over 100 lines in full – has just appeared in The Long Poem Magazine, Issue 32, eds. Linda Black and Claire Crowther. This brilliant magazine is one of the few outlets for poems stretching beyond the ‘competition’ mark of 40/50 lines only. Poets/translators again have the opportunity to comment on the work being published. This was my Introductory paragraph:

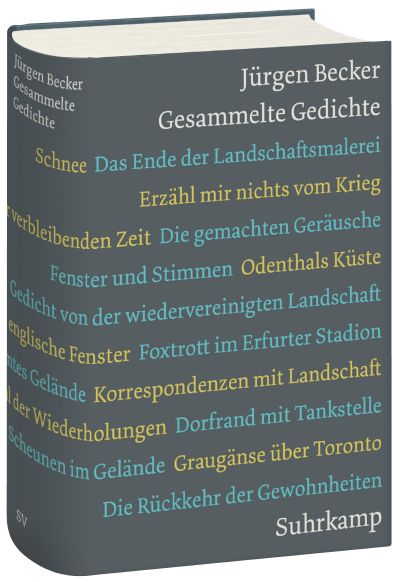

Given his 1000 page Collected Poems (Suhrkamp, 2022), it’s remarkable that Jürgen Becker’s work has been so little translated into English. This poem, published in his 1993 collection, Foxtrot in the Erfurt Stadium, is imbued with Becker’s sense of the changes in this particular part of Europe. The interleaving of the child’s and returning adult’s vision is what yields Becker’s characteristic poetic mode: a flickering between past and present, often without warning to the reader, a past frequently oppressed by the rise of fascism in the 1930s. The translator’s difficulties lie not in his word choices (Becker plainly describes, he states), but, to some degree, in his cultural references (here, the allusion to pimpf kids (cub, little rascal, little fart) is to members of the Hitler Youth), and, primarily, in dealing with his style of montage-composition, his commitment to ‘the apparently incidental’. Becker’s porous verse contains multitudes of perspectives, voices, inner and outer events, photos, maps, postcards, news, weather reports. In translation, it’s hard to flex, to permit these into English, and I have had to learn to trust Becker’s arrangements of them into long, semi-colon linked passages, utterly remote from conventional ‘lyric’. The opening 24 lines here elide landscape, weather, employment, domesticity, and history, then on to the natural world, compositional ideas, back to history. Becker is a great poet of the present moment and of the past. He grew up in Thuringia which, following World War II, lay in the Soviet occupation zone, later the GDR. By then, Becker’s family had moved to West Germany, and, after 1990, he often returned to these childhood landscapes. This poem was published in his 1993 collection, Foxtrot in the Erfurt Stadium. Becker worked for many years in German radio, and, in this poem, we might imagine a small production team visiting an un/familiar landscape in the East, perhaps where a childhood was spent, a place later abandoned.

Travel film; re-runs (extract)

the landscape: like corrugated cardboard, an enduring, fixed

motion, on a smoky grey day. The wind came

somewhere from below, from a region beneath

the weather chart; in the evening, we could no longer

reach our correspondents. We drove out

to the country house; we ate

Spanish green asparagus. It was a moment

from yesterday that rolled slowly past the shelf

with its yellow calendars and diaries and pictures;

something had begun,

and you’re aware of it,

the sound of that reiteration. You can … and

you allow it … push the off button; outside the window,

the blackbird flutters up, simply waiting

to be mentioned. Now you notice the way the paint

has peeled from the window frame, and where

the ants are coming from, in January the only

living creatures in the house. Perseverance pays off

at some point, even if you have little alternative

but to gather piece after piece together. Paint pots

in the shed, shades of green and white, but

we are waiting for a consistent light,

on either side of the house. Is it too late now,

to leave again

… lake shores, before they are all

accounted for, can still be appreciated, with sandy paths

reaching the purple horizon … subjunctive, without end;

a game of evasion that you can watch until you

whistle, or shout, and it’s nothing like awakening

from a dream. In the evening, we light a fire; it’s

a sudden, impromptu decision; then follows

the next draft of the letter: your sketches litter the table

… you no longer need a pass; highways,

the middle of the village … standing beside you

on the jetty; on the opposite side, the yellow ribbon

of the shoreline…

clips from the travel film just now

set going in the blink of an eye; then the meadow

is mown; there are a few old clumps of snowdrops

we leave standing. The fact is, we have missed out

on the moment of adulthood, even if, in the evening,

you say: never, not once, did the door open, from

which a little something left, and what you are now

entered in. The contrast, the changes … the fear has

been networked, so many of these shortcomings went

into production. Piano, from beyond French windows,

Shostakovich plays Shostakovich, and the life story

draws a curve out towards the northeast. Ice floes,

accumulating along the coast; in boots and furs,

walking over the frozen river, passing pimpf kids,

and old men, and a young woman who’s most likely

Polish, and you’re not going to stop staring at her

any time soon; freezing cold on the sledge back home,

your mother doesn’t live here anymore; the whole scene

darkens under the smoke of an engine pulling

the fast train to Lusatia . . .