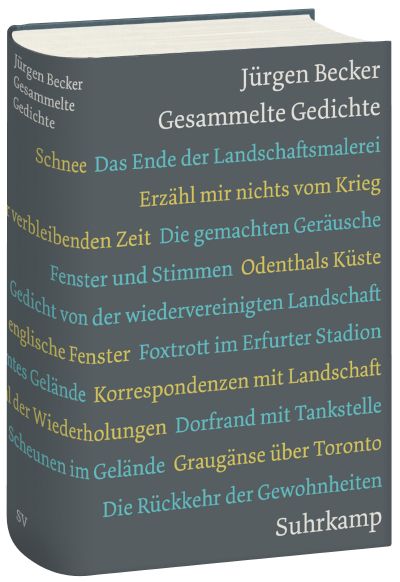

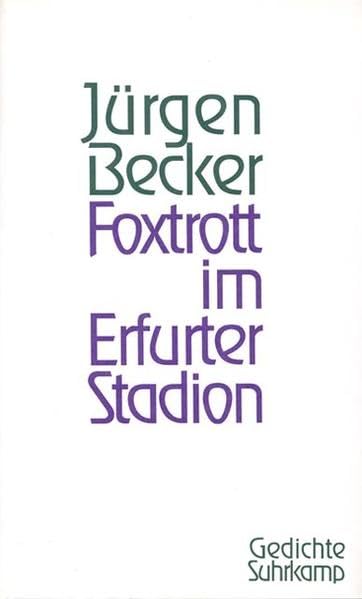

Following on from the publication in January 2025 of my translation of ‘Dressel’s Garden’, one of Jürgen Becker’s longer poems (which recently appeared on the USA site Asymptote Journal), three more poems by this fascinating German poet have just appeared in Shearsman magazine and our hope is (permissions permitting etc) that Shearsman Books will be publishing a full collection of his work in the near future. All these poems are taken from Becker’s crucial 1993 collection, Foxtrot in the Erfurt Stadium. The newly published poems are relatively brief so I thought I’d post two them here with a little bit of literary and historical context. (I’ll comment in a later post on the longest of the three poems now published by Shearsman).

In her Afterword to Jürgen Becker’s monumental 1000-page Collected Poems (2022), Marion Poschmann praises the poet as being ‘the writer of his generation who has most consistently exposed himself to the work of remembrance, who approaches the repressed with admirable subtlety and is able to reconcile his personal biography with the great upheavals of history.’ Likewise, in their adjudication, the 2014 Büchner Prize jury highlighted the way ‘Becker’s writing is interwoven with the times, with what is observed and what is remembered, what is personal and what is historical.’ Jürgen Becker’s own personal journey began on July 10, 1932, on Strundener Strasse, in Cologne. In August 1939, shortly before the outbreak of the war, his father was transferred from his place of work in Cologne to Erfurt in Central Germany. This was the beginning of the seven-year-old Becker’s experience of war and a post-war childhood in Thuringia. In 1947, the family left Erfurt and returned to West Germany. Becker has said about this period that there was never any thought of wanting to travel to the Eastern zone, let alone to the GDR, to see the places and landscapes where he’d spent his childhood years: ‘For a long time, I oriented myself solely towards western horizons; I lived, so to speak, with my back to the GDR; my childhood was separated by a border, seemingly closed’. (More of borders in a moment).

Becker’s interest in ‘events’ – political and historical – can clearly be seen in the short poem ‘Reporter’. Its subject never seems to become outdated (as I write this, Turkey is enforcing a crackdown on reporting – see the arrest and deportation of BBC reporter, Mark Lowen, very recently). Becker’s poem is not set in any particular time period, though the allusion to a ‘vast thing, fading away’ suggests an epoch of great change, one political system fading, another on the rise. I love the journalist’s reported observation that he ‘can only leave / when nothing else happens’. In Becker’s writing, there is always something else arising (history does not stop happening – as we see in this particularly fast-moving historical moment). I take the implication of the final 4 words to suggest that the reporter may well be ‘removed’ by the authorities from whatever the situation currently is (against his wishes by the sound of it) and that we will all become the poorer for that, more poorly informed, less capable of distinguishing the truth of things: ‘He will be missed’.

He barely looks at the camera; it almost seems

as if he’s talking to himself, a correspondence

with something on the unseen table, perhaps

with the pencil, the cigarette.

A slight tremor in the hands … who knows; anyway,

very likeable, nothing specific, more a murmur,

what can you say … cold weather and glimpses

along a street which is illuminated a little

by the snowfall; a leftover flag being stirred

by a wind machine. A vast thing, fading away

slowly … it has already disappeared, even before

a decree. He repeats it: he can only leave

when nothing else happens. He will be missed.

x

The second poem, ‘Meanwhile in the Ore Mountains’, bears strong similarities in that the specific time period (though not the setting) is left deliberately vague, though so many of the details in the poem possess a terrific (terrifying?) resonance for our own times. As to place, the Ore Mountains lie along the Czech-German border and borders are important in this poem. As I mentioned above, Becker was born in the eastern region of Germany, but from age 7, he was brought up in West Germany, and after the fall of the Wall in 1990, he’d often return to his (eastern) childhood landscape. The resulting blending of a child’s and adult’s vision is what gives rise to Becker’s characteristic poetic mode: a flickering between past and present, often without clear signalling, the past frequently haunted by the disturbing changes that happened in Germany in the 1930s. I’ll post the original German of this poem as well, as in what follows I’ll make a few observations about translation.

Though relatively brief, this poem is just one sentence, woven together with the conjunction ‘wie’ (translated here both as ‘how’ and ‘the way’). The weave is dense and as I’ve suggested it’s not really possible to tell whether what is observed – the children, the oil spill, the tree stump (resembling a body) – are contemporaneous or from different eras. My translation keeps these possibilities open: borders here are felt to be temporal, as well as geographical. The German word ‘Avantgarde’ has artistic as well as political implications, but my choice of ‘vanguard’ also brings out the militaristic connotations which are reinforced by the ‘spitzen, grünen Lanzen’ (‘sharp, green spears’) which are then swiftly transformed into a bunch of sprouting snowdrops. These flowers of Spring are interestingly referred to as a ‘Konvention’ and I retained the English equivalent, intending to suggest both a performance (something conventional, perhaps not genuine), as well as a political gathering or agreement (like the Convention on Human Rights). The ambiguity felt very relevant (and once again topical).

The final vivid, visual images – a TV screen observed through a window, a script on the screen, a woman talking, but she is inaudible to the observer – sum up Becker’s concerns about the media, political and historical change, borders real and imagined, exclusion, and the need to ask questions of those in power. Issues as real today as when the poem was written in the early 1990s.

Meanwhile in the Ore Mountains

Sitting still, watching how the afternoon below

waits for the dusk, the way snipers vanish

behind the remains of a wall and children run

after a white, armoured vehicle, the way a line

of hills, which marks a boundary, divides

the nothingness of snow from the nothingness of sky,

and along the frontier, one this side, another

along the other, fly the only two crows

to be found in this treeless landscape, the way

the iridescent pattern of an oil spill develops

with darkening edges, the way a tree stump

in the field becomes the shape of a body with

severed arms and legs, how, under the cherry,

the vanguard shows with sharp, green spears,

which later, over the next few days, assumes

the convention of snowdrops, how dark windows

are lit by screens, and on each screen appears,

at first, lettering, and then the face of

a woman who is soundlessly moving her lips.

x

Zwischendurch im Erzgebirge

Still sitzen und sehen, wie unten der Nachmittag

die Dämmerung erwartet, wie Scharfschützen hinter

einem Mauerrest verschwinden und Kinder

einem weißen gepanzerten Fahrzeug nachlaufen, wie

eine Hügellinie, die eine Grenzlinie ist, das Nichts

des Schnees vom Nichts des Himmels trennt, und

entlang der Grenze, die eine diesseits, die andere

jenseits, fliegen die beiden einzigen Krähen, die

es in dieser baumlosen Landschaft gibt, wie

das changierende Muster eines Ölteppichs entsteht

mit dunkler werdenden Rändern, wie auf der Wiese

ein Baumstumpf die Form eines Körpers annimmt mit

abgeschlagenen Armen und Beinen, wie unterm Kirschbaum

sich die Avantgarde zeigt, mit spitzen, grünen Lanzen,

die später, in den nächsten Tagen, die Konvention

der Schneeglöckchen annimmt, wie in dunklen Fenstern

Bildschirme aufleuchten und auf jedem Bildschirm

zuerst eine Schrift und dann das Gesicht einer Frau

erscheint, die lautlos die Lippen bewegt.