Marvin Thompson’s debut collection from Peepal Tree Press is a PBS Recommendation and deservedly so. All too often we are informed of the arrival of a startling voice, usually a vital one, striking a new note in English poetry. Well, this is the real deal: a superbly skilled practitioner of the art whose work is driven by two seemingly opposing forces. Thompson writes with a disarming sense of autobiographical honesty, often about domestic life, as a father and a son. Yet he can also create fictional characters with detailed and convincing voices and backgrounds. What holds these divergent styles together is his demonstrated conviction that the past (as an individual or as a member of an ethnic or cultural group) interpenetrates the present.

Marvin Thompson’s debut collection from Peepal Tree Press is a PBS Recommendation and deservedly so. All too often we are informed of the arrival of a startling voice, usually a vital one, striking a new note in English poetry. Well, this is the real deal: a superbly skilled practitioner of the art whose work is driven by two seemingly opposing forces. Thompson writes with a disarming sense of autobiographical honesty, often about domestic life, as a father and a son. Yet he can also create fictional characters with detailed and convincing voices and backgrounds. What holds these divergent styles together is his demonstrated conviction that the past (as an individual or as a member of an ethnic or cultural group) interpenetrates the present.

‘Cwmcarn’ is a poem in an apparently simple autobiographical mode, the narrator out camping in Wales with his two children. He has been reading them to sleep with pages from Maggie Aderin-Pocock’s biography but feeling a bit guilty about not finding a book about “a Mixed Race // scientist / for my // Mixed Race / children”. The thought leads him to reflect on his own childhood’s confusions about racial identity, being born in north London to Jamaican parents, but knowing he was ultimately “by ancestry, / African”. He recalls the hurt of being “branded” English, not Jamaican, and then worries about the consequences of his children identifying “as White / in a Britain // that will call them / Black”. As you can see, Thompson’s chosen form is reminiscent of what Heaney (around the time of North) called his ‘artesian’ form of skinny-thin poems and the same effect of drilling down into the past is achieved here.

Several of the same components are redeployed in the sequence ‘The One in Which…’ (with a nod to Friends). The narrator is driving his kids to the cinema, playing “Joe Harriott’s abstract jazz” in the car. The children not surprisingly consider the music angry, sad and crazy. The father is not unhappy with this: “my Mixed Race children are listening / to something I want them to love”. He himself wonders if it’s “upbringing // or brainwashing” but the music “sings // Africa’s diaspora and raises skin to radiance”. (Listen to Thompson read this poem here) This last phrase is a wonderful play on aspects of light and darkness and the consciousness of the power of the past is extended with the father’s memories of the 1985 disturbances on Broadwater Farm in Tottenham. What Thompson does so convincingly and without strain is to present the individual’s stream of consciousness as it streaks in and out of the past and present. The third section of this sequence opens with a simile that should come to be seen to rival the ground-breaking significance of Eliot’s Prufrockian evening spread out against the sky “Like a patient etherised upon a table”. Welsh storm clouds are the subject here and the comparisons that flood the poem are drawn from the past of Jamaican, American, Haitian and African roots:

Several of the same components are redeployed in the sequence ‘The One in Which…’ (with a nod to Friends). The narrator is driving his kids to the cinema, playing “Joe Harriott’s abstract jazz” in the car. The children not surprisingly consider the music angry, sad and crazy. The father is not unhappy with this: “my Mixed Race children are listening / to something I want them to love”. He himself wonders if it’s “upbringing // or brainwashing” but the music “sings // Africa’s diaspora and raises skin to radiance”. (Listen to Thompson read this poem here) This last phrase is a wonderful play on aspects of light and darkness and the consciousness of the power of the past is extended with the father’s memories of the 1985 disturbances on Broadwater Farm in Tottenham. What Thompson does so convincingly and without strain is to present the individual’s stream of consciousness as it streaks in and out of the past and present. The third section of this sequence opens with a simile that should come to be seen to rival the ground-breaking significance of Eliot’s Prufrockian evening spread out against the sky “Like a patient etherised upon a table”. Welsh storm clouds are the subject here and the comparisons that flood the poem are drawn from the past of Jamaican, American, Haitian and African roots:

Mountain clouds clench like a Maroon’s fists

as she sleeps beyond the sugarcane and soldier’s guns with her sons

and daughters in Jamaica’s hills – fists like Jack Johnson’s,

an 18th Century Haitian’s or an ANC activist’s.

It will be objected that there are one (or two) too many similitudes here but surely that is the point: the vividness, dynamism and vitality of these images drawn from the past make up an irresistible force to the father in the poem.

The astonishingly titled ‘Whilst Searching for Anansi with my Mixed Race Children in the Blaen Bran Community Woodland’ makes Thompson’s point over again: the (playful) search for an African folkloric trickster figure (in the shape of a spider) in the Welsh woodlands is not being flaunted here, it is taken to be perfectly normal. In fact, the family don’t discover Anansi at all but an apparently dead fox. But the father’s head is full of his previous night’s dream of Mark Duggan’s shooting by police in 2011 which is also mixed with memories of 1985 again, when “rage had spread / like an Arab Spring”. The delicacy of the descriptions of the fox, combined with the children’s concern for it (it is still alive), become correlatives for the father’s preoccupations with the past. These latter thoughts again streak backwards – in appropriately dream-like fashion – to finding Duggan lying now in the Gold Coast, in ancestral times, “chains ready on docked ships from London”. There is no wrench when the father suddenly resurfaces in the present, worrying, “Will Britain / learn to love my children’s melanin?” The compassion shown towards the injured fox by the family, taking it to a vet, reflects some hopefulness perhaps.

Road Trip does indeed indicate the possibilities of compassionate responses to racial and social divides, the importance of an empathetic imagination which yet does not iron out the kinds of historical differences that Thompson is clearly exploring. ‘Rochelle’ is a 6-poem sequence demonstrating this point as well as showcasing the more fiction-making aspects of Thompson’s talent. The narrative is from Rochelle’s point of view, a young black girl driving to London from Wales to support her sister who has had a miscarriage. On the way, she picks up a young black hitchhiker, Kite, and his back story is also developed in the poems. The form here – and used elsewhere in the book – is a form of loose terza rima, half rhymed mostly, with not much variation in the rhyme sounds. The effect is a kind of circling, interweaving with some sense of a slow progression – which is marvellously apt for the exploration of the past’s breaking into the present and this sequence’s sense of a tentative break-out of the established cycle. Rochelle’s mercy dash is actually undertaken pretty equivocally because she and her sister have much rivalry and bad blood from the past. This sense of distance and alienation is also reflected in the hiker who seems a silent, morose figure. But somewhere near the Hangar Lane gyratory, Rochelle pulls over because there is a horse in the road. The animal – like the fox earlier – provokes a tender response from Kite which opens up the relationship between the two people. Kite’s background has been as difficult as Rochelle’s and now he is returning home to care for his mother who has dementia. A friendship is struck up and the conversation with Kite’s mother persuades Rochelle to phone her sister with a good deal more sisterly compassion in her heart.

Thompson is good at sketching in such characters and developing relationships, investing moments and scenes with a mysterious intensity, but the tone is not usually so optimistic. ‘The Weight of the Night’ is a pair of prose pieces in which the past – of sexual guilt, male presumption and final reckoning – proves to be an immoveable obstacle to a marriage. And though there is something comic in the germ of the idea in ‘The Many Reincarnations of Gerald Oswald Archibald Thompson’ (a father’s ghost returns to his son, telling of his many previous lives), the reincarnations are all in the form of British military figures from Peterloo, the Boer War, Aden, the Bengal Famine of 1943 and the Falklands campaign. The theme is imperialism and social injustice and the father’s chuckling about his actions creates an uncrossable divide between him and his son. I don’t know that I fully understand Thompson’s intentions in this sequence which again uses the ‘artesian’ form, and the surreal quality of some of the fictionalising here makes things harder to interpret. But the past – and perhaps the older generations’ complicity in the many injustices adumbrated – falls as a dead weight onto the present, even in the son’s recalling his father’s recent death from cancer.

I’m impressed at the editorial control shown in this collection. I suspect there are many false starts or even other successes lying in Thompson’s files. There is a generosity of creative energy here which one suspects could display itself at much greater length (a novel perhaps?). The concluding sequence of 3 monologues, ‘The Baboon Chronicles’, is a case in point. Thompson creates a dystopian world (not far from our own – or at least Pontnewynydd) in which Black and White live uneasily beside each other but the streets are also occupied by baboons. These creatures are treated with disgust and abuse by the humans. The White characters also seem to abuse the Black people on a reflex with insults like “’boon”. In monologues by Stephen, Sally and Suzi, Thompson does make points about racism, the othering of those perceived as different, injustice and (latterly) police violence but what is more impressive is the empathetic imagination on show in the creation of these characters’ voices. Thompson possesses in abundance Keats’ negative capability and, as much as he shows how the past, racial and cultural upbringing and memories of injustice lays so heavily on individual identity, Road Trip also shows the possibility of imagining into the Other (of listening as all the great jazzers do) which, rather than a retreat behind the Pale, must be the way towards a more just and equitable world.

I’m impressed at the editorial control shown in this collection. I suspect there are many false starts or even other successes lying in Thompson’s files. There is a generosity of creative energy here which one suspects could display itself at much greater length (a novel perhaps?). The concluding sequence of 3 monologues, ‘The Baboon Chronicles’, is a case in point. Thompson creates a dystopian world (not far from our own – or at least Pontnewynydd) in which Black and White live uneasily beside each other but the streets are also occupied by baboons. These creatures are treated with disgust and abuse by the humans. The White characters also seem to abuse the Black people on a reflex with insults like “’boon”. In monologues by Stephen, Sally and Suzi, Thompson does make points about racism, the othering of those perceived as different, injustice and (latterly) police violence but what is more impressive is the empathetic imagination on show in the creation of these characters’ voices. Thompson possesses in abundance Keats’ negative capability and, as much as he shows how the past, racial and cultural upbringing and memories of injustice lays so heavily on individual identity, Road Trip also shows the possibility of imagining into the Other (of listening as all the great jazzers do) which, rather than a retreat behind the Pale, must be the way towards a more just and equitable world.

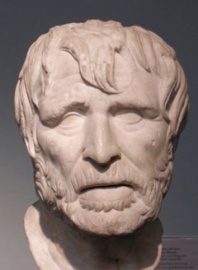

Did you know Hesiod probably pre-dates Homer? Hesiod is aware of the siege of Troy but he makes no reference to Homer’s Iliad. He’s usually placed before Homer in lists of the first poets. The other striking aspect of Works and Days is that (unlike Homer) he is not harking back to already lost eras and heroic actions. Hesiod talks about his own, contemporary workaday world, offering advice to his brother because they seem to be in a dispute with each other. Hesiod’ anti-heroic focus is an antidote to the Gods, the top brass and military heroes of Homer. Most of us live – and prefer to live – in Hesiod’s not Homer’s world.

Did you know Hesiod probably pre-dates Homer? Hesiod is aware of the siege of Troy but he makes no reference to Homer’s Iliad. He’s usually placed before Homer in lists of the first poets. The other striking aspect of Works and Days is that (unlike Homer) he is not harking back to already lost eras and heroic actions. Hesiod talks about his own, contemporary workaday world, offering advice to his brother because they seem to be in a dispute with each other. Hesiod’ anti-heroic focus is an antidote to the Gods, the top brass and military heroes of Homer. Most of us live – and prefer to live – in Hesiod’s not Homer’s world. He seems to have been a poet-farmer who makes sure we are aware that he has already won a literary competition at a funeral games on the island of Euboea. His prize-winning piece may well have been his earlier

He seems to have been a poet-farmer who makes sure we are aware that he has already won a literary competition at a funeral games on the island of Euboea. His prize-winning piece may well have been his earlier  There are further reasons to set to work in the very nature of the cosmos and the human world. Hesiod tells the Pandora story here. Zeus causes the creation of a female figure, Pandora, as a way of avenging Prometheus’ pro-humankind actions (stealing fire from the gods, for example). Her name suggests she is a concoction or committee-created figure from contributions from all the Olympian Gods. She is given a jar which she opens: “ere this the tribes of men lived on earth remote and free from ills and hard toil and heavy sickness [. . .] But the woman took off the great lid of the jar with her hands and scattered all these and her thought caused sorrow and mischief to men” (tr. Evelyn-White). Hesiod’s locating of the root of human sorrow in the actions of a woman echoes the Christian story of the loss of Paradise and it is one of the reasons why Hesiod has been accused of misogyny, though as Stallings suggests, he’s not any more complimentary about the males of the human race.

There are further reasons to set to work in the very nature of the cosmos and the human world. Hesiod tells the Pandora story here. Zeus causes the creation of a female figure, Pandora, as a way of avenging Prometheus’ pro-humankind actions (stealing fire from the gods, for example). Her name suggests she is a concoction or committee-created figure from contributions from all the Olympian Gods. She is given a jar which she opens: “ere this the tribes of men lived on earth remote and free from ills and hard toil and heavy sickness [. . .] But the woman took off the great lid of the jar with her hands and scattered all these and her thought caused sorrow and mischief to men” (tr. Evelyn-White). Hesiod’s locating of the root of human sorrow in the actions of a woman echoes the Christian story of the loss of Paradise and it is one of the reasons why Hesiod has been accused of misogyny, though as Stallings suggests, he’s not any more complimentary about the males of the human race. It’s certainly the lazy, self-serving, arrogant younger brother who forms the focus of the rest of the poem: “So Perses, you be heedful of what’s right . . . So Perses, mull these matters in your mind . . . Fool Perses, what I say’s for your own good” (tr. Stallings). It’s true that his name gradually fades from the text in the final 500 lines but the torrent of imperatives, offering advice and guidance on a range of practical issues, often sounds like haranguing from a concerned, perhaps slightly pissed off, brother. Much of this material is phenological – when to sow crops, when to harvest, when to shear your sheep. In winter, don’t hang around the blacksmith’s forge where other wasters gather to chat and pass the time. It’s safe to put to sea when the new fig leaves are the size of crow’s feet.

It’s certainly the lazy, self-serving, arrogant younger brother who forms the focus of the rest of the poem: “So Perses, you be heedful of what’s right . . . So Perses, mull these matters in your mind . . . Fool Perses, what I say’s for your own good” (tr. Stallings). It’s true that his name gradually fades from the text in the final 500 lines but the torrent of imperatives, offering advice and guidance on a range of practical issues, often sounds like haranguing from a concerned, perhaps slightly pissed off, brother. Much of this material is phenological – when to sow crops, when to harvest, when to shear your sheep. In winter, don’t hang around the blacksmith’s forge where other wasters gather to chat and pass the time. It’s safe to put to sea when the new fig leaves are the size of crow’s feet. These are the passages that, around 29BC, inspired Virgil to his own farmer’s manual, the Georgics. Hesiod ends his poem in a rather perfunctory manner, roughly saying he who follows this good advice will become “blessed and rich”. But given Pandora’s jar and the Iron Age we live in, even this seems a mite optimistic. And of course, Perses never gets the chance to speak for himself. But I guess the tensions between his brother’s call for social and religious conformity and Perses’ individualistic disobedience to the demands of the gods and the sense of what is best for a society have gone on to form the basis of the continuing Western literary canon. And does any of this help with Brexit? I conclude (largely with Hesiod) the bleeding obvious: it’s complicated – solutions must be negotiated, don’t hope for some golden age because in a fallen, less-than-ideal, complex society it’s better for the future to be decided in the glacier-slow committee rooms of a plurality of voices than in the stark divisions and dramas of the battlefield. Work hard – have patience – don’t buy into fairy tales of a recoverable golden age.

These are the passages that, around 29BC, inspired Virgil to his own farmer’s manual, the Georgics. Hesiod ends his poem in a rather perfunctory manner, roughly saying he who follows this good advice will become “blessed and rich”. But given Pandora’s jar and the Iron Age we live in, even this seems a mite optimistic. And of course, Perses never gets the chance to speak for himself. But I guess the tensions between his brother’s call for social and religious conformity and Perses’ individualistic disobedience to the demands of the gods and the sense of what is best for a society have gone on to form the basis of the continuing Western literary canon. And does any of this help with Brexit? I conclude (largely with Hesiod) the bleeding obvious: it’s complicated – solutions must be negotiated, don’t hope for some golden age because in a fallen, less-than-ideal, complex society it’s better for the future to be decided in the glacier-slow committee rooms of a plurality of voices than in the stark divisions and dramas of the battlefield. Work hard – have patience – don’t buy into fairy tales of a recoverable golden age.